How the Trump Administration Should Deal With a Changing China

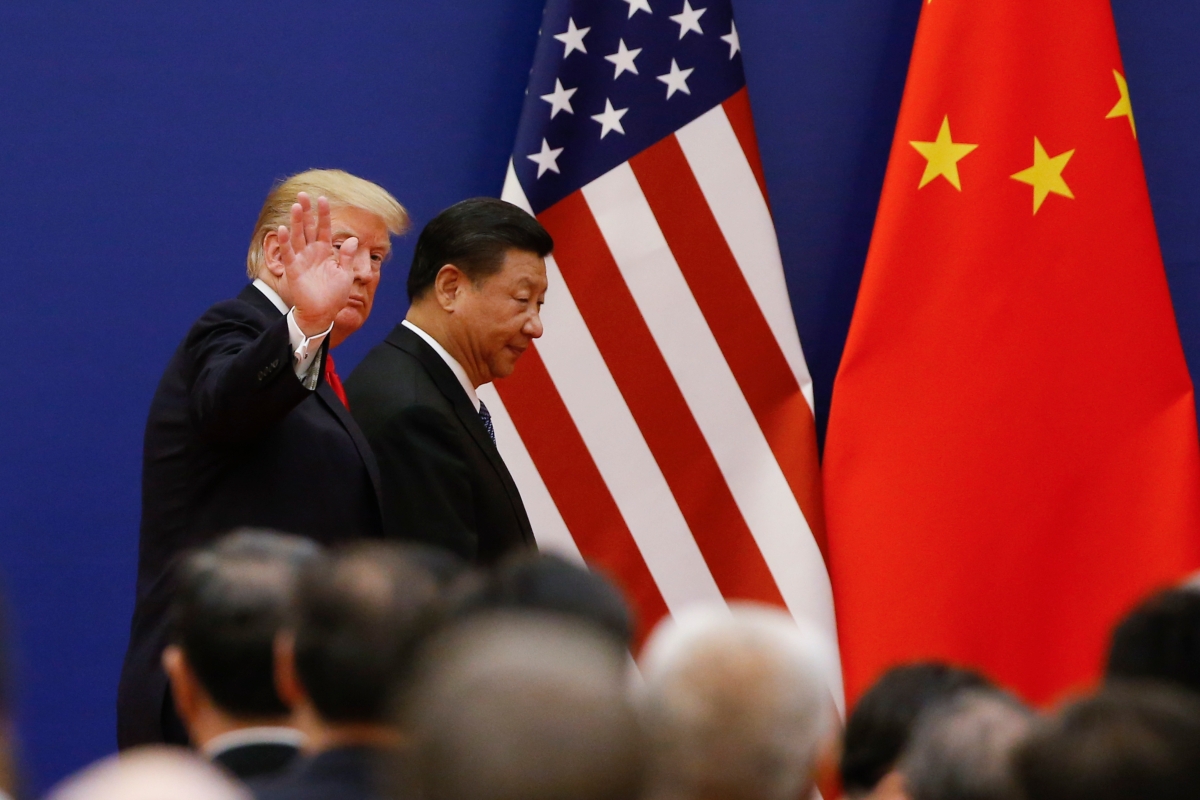

A new task force report argues that the U.S. must change the trajectory of its relationship with China. (Thomas Peter-Pool/Getty Images)

Thomas Peter-Pool/Getty Images

During his recent State of the Union address, U.S. President Donald Trump had this to say about China:

We are now making it clear to China that after years of targeting our industries, and stealing our intellectual property, the theft of American jobs and wealth has come to an end. Therefore, we recently imposed tariffs on $250 billion dollars of Chinese goods — and now our Treasury is receiving billions and billions of dollars.

But I don’t blame China for taking advantage of us — I blame our leaders and representatives for allowing this travesty to happen. I have great respect for President Xi, and we are now working on a new trade deal with China. But it must include real, structural change to end unfair trade practices, reduce our chronic trade deficit, and protect American jobs.

In a speech — and presidency — noted for divisive rhetoric, it was one of the few lines that elicited a standing ovation from Republicans and Democrats alike.

Two years into the Trump era, the relationship between the United States and China, the world’s two largest economies, appears to be undergoing a fundamental transformation, driven as much by changes within China as by policies pursued by the idiosyncratic American president.

What exactly is happening — and what the U.S. should do next — are the key questions informing Course Correction: Toward an Effective and Sustainable China Policy. The 47-page report was released Tuesday by the Task Force on U.S.-China Policy, a group comprised of a who’s who of American Sinologists and chaired by Orville Schell, Arthur Ross director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations; and Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California, San Diego.

Course Correction is a sequel to the task force’s 2017 report outlining recommendations for the then-brand-new Trump administration. Two years later, the authors recommend that Washington employ the principle of "smart competition," which Schell said means that the U.S. should "be much more forceful in responding to various kinds of Chinese abuses, inequities, and failures to live up to their agreements, while at the same time, keeping the door open to actively working together on areas on common interest."

Ahead of the launch, here are some of the key takeaways.

China’s Role in the Global Ecosystem Has Changed

In the decades that followed its embrace of market reforms in 1978, China grew rapidly through investment in infrastructure and exports of labor-intensive manufactured goods. It sought entry into the U.S.-led global economic order and received it through accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. But the China of 20 years ago no longer exists: Its per capita GDP grew from $870 (converted at exchange rates then) to $8,848 in 2017.

"China has thrived in the global economic system," the task force authors write, adding that "[it] has responded to this economic success by asserting its intention to compete aggressively and feature itself prominently as a leader in an enormous range of the most sophisticated sectors."

This trend is a natural consequence of China’s rising prosperity — but the country has also nurtured homegrown companies by protecting them from foreign competition. This has created an uneven playing field where Chinese firms enjoy unfettered access to foreign markets but the reverse isn’t true, a clear violation of the spirit and letter of the WTO, a point made in Course Correction:

"These violations and this lack of reciprocity destroy any justification for a middle-income China to demand or be accorded special treatment in any future negotiations."

China has also, in recent years, shown a similar assertiveness in its foreign policy. In 2016, the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea rejected China’s claim to sovereignty over the entirety of the South China Sea — a ruling that Beijing has largely ignored by continuing to construct military facilities on disputed islands and reefs, actions that have stoked tensions with neighbors such as Vietnam and the Philippines.

Further afield, Beijing has become a player throughout the region and beyond through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious (and controversial) economic development plan linking some 65 countries that together comprise around 30 percent of global GDP. China has also stepped up industrial espionage and cyber theft against the United States, an activity that could, according to the task force authors, "erode America’s technological lead and undermine not only America’s economic advantages but its ability to achieve military superiority."

Then there’s what’s happening inside of China, which, as the report argues, has ripple effects on the outside world and feeds back into the assertiveness mentioned above. As recently as a decade ago, it was fashionable to predict that as it continued to grow richer, China would also liberalize its political system. Instead, the opposite has happened. Under President Xi Jinping, Beijing has increased censorship, expanded surveillance, and limited space for personal freedoms throughout the country. This trend has been especially egregious in Xinjiang, China’s far-western province, where the government has detained as many as one million Muslim Uighurs in euphemistically-named "re-education camps" that critics claim amount to ethnic cleansing. Finally, Xi himself has upended political norms in China by refusing to name a successor, paving the way for him to govern indefinitely.

The consequences of this shift, the Task Force authors write, is grave:

A more repressive Chinese regime is more dangerous to the international community. When it is exempt from effective oversight by its own public, it is more likely to engage in external adventurism without concern for the cost to the Chinese people or to the world. It is also more likely to promote authoritarian values in countries where it has influence and to train elites in those countries in methods of information control and repression. A regime that violates international human rights law is more likely to violate other international laws, including in trade, finance, and territorial disputes.

The Trump Administration Has Needlessly Worsened Tensions With China

Given the nature of China’s evolution, a different American approach to the country was needed and, largely, delivered by the Trump administration during its first two years in power. But the task force authors argue that Trump, through his idiosyncratic obsession with trade and his disdain for international alliances, has made the relationship more complicated than it needs to be.

On his third day in office, Trump fulfilled a campaign promise by withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation trade pact that would have bound China to higher standards of reciprocity and fairness. Since then, U.S. trade policy toward China has focused on the bilateral trade deficit — a pet issue of Trump’s — rather than the question of fairness. The U.S. and China are now involved in trade negotiations which, if they fail, would result in substantial new tariffs being imposed on the Chinese economy.

“Trump’s high state of paranoia — which causes him to naturally view foreign powers as predatory, has led to his version of pushback against China via higher tariffs, concern about trade deficits, and so forth,” said Schell in a recent Asia Society interview.

The task force authors do not recommend that Trump revert to the status quo ante of U.S.-China relations — even if such a solution were possible. Instead, they suggest that the U.S. stand up for the international economic system it constructed.

"This does not equate to a demand that China change its political system or abandon its aspirational industrial policies to become a technological superpower," they write. "Those are China’s decisions. But it is still possible for China to pursue its ambitious agenda while playing by rules of fair competition."

Decoupling From China Is Not an Option — But Turbulence Looms

In a recent appearance at Asia Society, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman quipped that "one country, two systems" — the formulation governing China’s relationship with Hong Kong — more accurately reflects the U.S.-China relationship. Even with the increased tensions characterizing the last few years, the two countries remain deeply entwined, something that has, arguably, been a force for good for both. But times have changed. Said Schell:

I think all of us feel that we are at an extraordinary and troubled moment of inflection where the assumptions that we all had for the last 30-40 years — namely that engagement would slowly work its way and over time we would become more convergent with China rather than less, that China would continue to reform and change, that if there could be a few more ballet troupe exchanges, educational interactions, and increased trade, we would grow closer together rather than further apart — is under serious question by an increasing number of my generation of China specialists.

That doesn’t mean that further attempts to steer China toward international norms are futile, however.

"If properly managed, a high level of economic integration would enhance the ability of the U.S. and partner countries to pressure China to conform to international norms (since China’s prosperity depends in part on this very integration)," the task force authors write. "Maintained integration would also increase the incentives to resolve security and political conflicts without resort to arms."