Fiction From Orville Schell: On the Tragic Sweep of Chinese History

Orville Schell, the Arthur Ross director of Asia Society's Center on U.S.-China Relations, is one of the United States' most accomplished Sinologists. He has published 11 non-fiction books about China over the last four decades, and his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and many other publications.

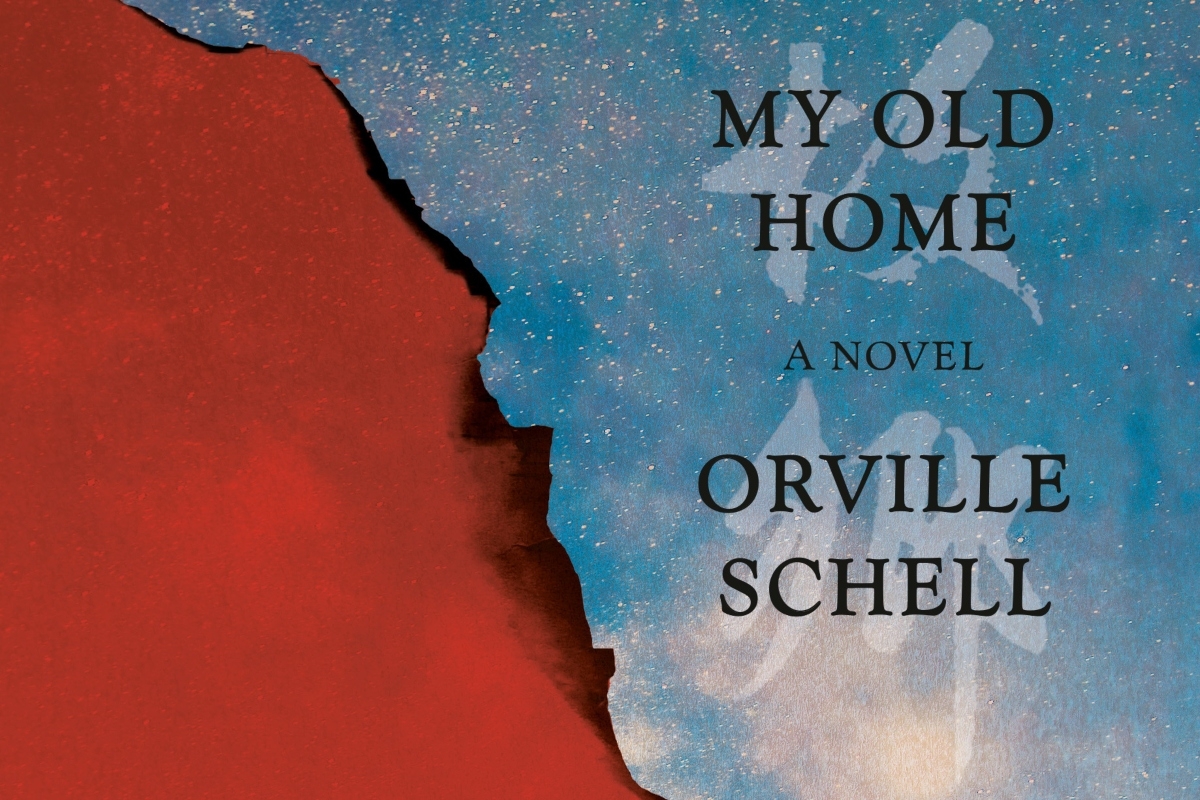

What Schell hasn't done is publish fiction — until now. His debut novel My Old Home takes us on a journey through China, from the rise of Mao Zedong in 1949 to the Tiananmen Square uprising in 1989, as a classical musician and his son are swept away by a relentless series of devastating events. Through their lives, we follow the fault line between the United States and China — a divide that at times has been narrow and easily crossed, while at other times perilously wide. At a time when this divide is once again widening, Schell’s fictional characters speak volumes about the agonies of separation that may yet again become a reality.

My Old Home has received ample advanced praise. “Absorbing, perceptive, heartbreaking, Orville Schell’s epic novel is a devastatingly true and moving portrait of what two generations of educated Chinese have experienced through the ordeal of the revolution and throes of reform," wrote the author and journalist Zha Jianying. Former U.S. ambassador to China Winston Lord called it "a dazzling novel that is sweeping in its historical canvas and intimate in its psychological insights."

You can purchase My Old Home, which will be released on March 9, at AsiaStore. The launch event will be held on March 9 at 4 p.m. New York time and will feature a conversation between Schell, Zha, and Asia Society President and CEO Kevin Rudd about the novel. The following is an excerpt from My Old Home.

Without Destruction There Can Be No Construction!

Long after the sky had drained of daylight, Li Tongshu (李同书) had still not arrived back home. As Chairman Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (伟大的无产阶级文化大革命) gathered a frightening momentum in the summer of 1966, he rarely returned home before dark and his 14-year-old son, Li Wende (李文德), often found himself sitting alone in their sparsely furnished room inside the once-elegant complex of gardens and halls that was known as Willow Courtyard (柳园). Besides two beds, a small round wooden table, a wardrobe, and a tall wooden case with glass doors to protect the books and music inside from the dry dustiness of Beijing, the only piece of furniture of any distinction was a Steinway upright piano.

Li Wende, known as Little Li in the neighborhood, was an unusually handsome boy, tall for his age but with a look of tentativeness that played about his eyes. As he sat on his father’s piano bench and waited, the fall wind whistling under the eaves of the sloping tiled roof made the single lightbulb hanging from the rafters swing and cast ominous, undulating shadows across the silent room. When, at last, footsteps sounded outside, Little Li ran to the door. Seeing the familiar silhouette of his father walking from the gate with his head lowered and shoulders hunched against the brisk fall night, he felt relieved. But as soon as he stepped through the door, his somber expression made the boy’s heart sink.

“Where were you?” he anxiously asked his father.

“I had to get some things at the Conservatory,” he answered, and then wordlessly set about preparing some cold steamed buns and pickled vegetables for dinner.

When they finally sat down to eat and he took one of his son’s hands in his own, and very softly he intoned: “Almighty God, we thank you for this food. Bless us and keep us, make your light to shine upon us and be gracious unto us.”

Because religious expression of any kind was forbidden, Little Li usually felt uneasy during these moments of whispered prayer, but tonight he felt reassured by his father’s hand.

“Are you ... ?” he began.

“This afternoon Red Guards dragged Ma Sicong to the Conservatory for a struggle session [批斗会],” interjected his father. “They attacked him as a ‘bourgeois intellectual’ [资产阶级知识分子] and a ‘Christian’ [基督徒], capped him with a dunce hat, taunted him as an ‘ox ghost and a snake spirit’ [牛鬼 蛇神], and then paraded him around the courtyard.”

“How do you know?” asked Little Li with alarm.

“I saw them.”

“Did anyone help Professor Ma?”

“No.” Li Tongshu cast his eyes downward, afraid to let his gaze meet that of his son. “Now, I’ve been told I am on the Red Guards’ list.” Little Li froze with fear.

With Beijing streets besieged by Red Guard actions, Little Li and his friend Little Wang had found all the drama exciting. But now as he studied his father’s somber face, he felt only guilt and regret.

“For what crimes are you on their list?” asked Little Li. Other people might be secret “capitalist agents” or “counterrevolutionaries,” but his own father?

“For my U.S. training, your American mother, and my love of Western music.”

“Will they demand a confession?”

“If one has committed no wrong, how can one confess?” riposted Li Tongshu defiantly. Then, in a softer tone, “In case anything happens to me, you must promise you’ll always ... ”

“But what can happen to you, Father?”

“We are in uncertain times, son.”

“But ... ”

“If anything does happen,” he continued, “promise you’ll do everything Granny Sun tells you and always honor our family name.” His voice cracked with emotion.

Granny Sun was the elderly widow who lived across the yard. She’d been married to a professor of literature from Yanjing University who’d once owned their entire courtyard complex of halls, gardens, verandas, and ponds, where his extended family and all its servants had lived for generations. However, Willow Courtyard was nationalized by Mao’s new revolutionary government in 1949, and partitioned up among a host of new tenants; Granny Sun, her husband, and their young daughter were forced to move all their Ming Dynasty furniture, artwork, books, and papers into a single hall. After arriving from San Francisco, Li Tongshu and his American-born wife, Vivian Knight, were assigned the room across the yard from theirs. A short while later, Professor Sun passed away from heart failure; Granny Sun was sure he’d died from dispossession of his beloved family home. However, she bore no grudges against the others who’d moved into their former home. In fact, after her daughter was assigned a job in Tianjin, she’d taken a special liking to Little Li.

Li Tongshu was quietly cleaning up after dinner when, just as a wild animal freezes upon hearing the snap of a twig in the forest, he suddenly froze. Holding a bowl in one hand and the kitchen cleaver in the other, he walked to the front door and cracked it open to listen. From the other side of the gray brick wall that surrounded their courtyard came the muffled din of agitated voices and the thudding of a drum. A moment later, a strident pounding sounded on their gate.

“But what is it?” a panicked Little Li asked.

“You must put on your coat,” ordered his father.

“What is it?” His father did not answer. Instead, as if he were acting out a script long since committed to memory, he walked to his piano, sat down on the bench, lifted the fallboard, positioned his slender hands over the keyboard, and began to play J. S. Bach’s chorale “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” As the music suffused the room like a sweet fragrance, it reminded Little Li of how his father had played such chorales at night when he was younger, as he fell asleep. Whenever his father played this particular transcription, he always began with the simple hymnlike melody, before slowly building the piece from the bottom up, part by part, as he imagined Bach had composed it. As he played, he sang along softly:

Glad am I who have my Saviour

From him will I never part.

He restoreth my sagging spirits,

Be I sad or sick at heart.

While cares may vex and troubles grieve me,

Yet will Jesus never leave me.

Little Li had always waited with anticipation for the moment when the descant line finally entered before allowing himself to float off to sleep on the wings of the chorale’s lullaby-like purity. But, whereas Li Tongshu usually played chorales with extraordinary gentleness, now his eyes were closed and his face upturned, as if he were straining to hear some faraway call. As the din in the alley swelled, he pounded out the chorale melody with ever fiercer resolution. Then, just as he introduced the familiar obbligato, the front gate flew open with a splintering crash, and the cacophony of hostile, hoarse voices, pounding drums, and clashing gongs grew suddenly louder. From watching other “counterrevolutionary elements” (反革命分子) paraded and attacked in public, Little Li knew his father’s hour of judgment had arrived.

“Down with the American spy Li Tongshu!” shrieked an angry voice from the shadows. “Down with all bourgeois music and foreign spies!” another voice responded. Li Tongshu continued to stubbornly hammer out the chorale.

“Father!” cried Little Li, running to the piano. “You must stop!” But, as if music might somehow tame the strident voices outside, he kept playing. “They’re in the courtyard! Stop!”

Only when he tugged at his sleeve did his father open his eyes. But instead of stopping, he continued playing. Just then a tall Red Guard in a khaki-colored greatcoat appeared on the veranda and, surprised to see a boy standing beside a grown man at a piano, cast a hesitant glance back toward his comrades, who’d fallen silent. As the music floated through the open door out into the darkness, the intruders seemed unsure how to proceed against such unexpected enemies of the people, and, like a film projector frozen on a single frame, for a moment the scene remained in a state of suspended animation.

“Long Live Chairman Mao!” a voice finally cried out.

The following excerpt of My Old Home is courtesy of Penguin Random House.