Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s Relations with Asia

Sean Foley

September 21st, 2020

"The relationship between India and Saudi Arabia is in our DNA."

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"We stand ready to strengthen cooperation with China."

Mohammed Bin Salman

Section One

Overview

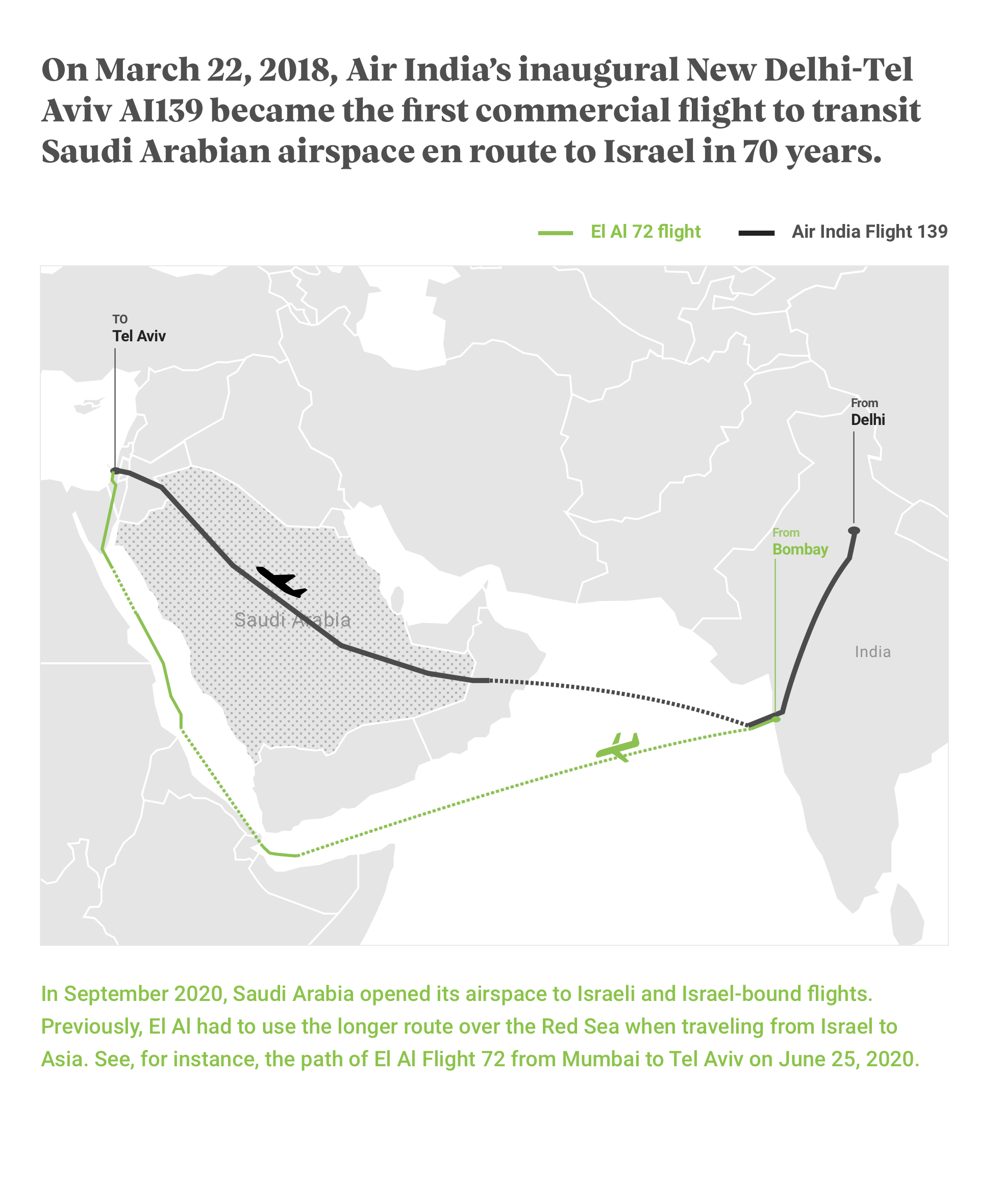

On March 23, 2018 Air India 139 arrived in Tel Aviv, becoming the first commercial flight to transit Saudi airspace to travel to Israel. Because the flight had traveled over Saudi Arabia and Oman, it arrived two hours faster than the same flight between India and Israel on El Al, which utilizes a more circuitous route through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Although Riyadh had rejected Washington’s request to also allow El Al to travel through Saudi airspace, there was a sense of optimism about what the new Air India flight could mean for the future of the region. Speaking to reporters at Ben Gurion Airport, Yariv Levin, Israel’s Tourism Minister, hailed the “new era” where India had created an “important bridge… not only between India and us but also between Israel and other countries in this region.” With this new route, Air India 139 has become a commercial success—carrying over a million passengers in 2019.

Riyadh’s decision to permit Air India to use its airspace to fly to Israel reflected an important shift in Saudi policy over the previous two decades, as the country’s leadership has increasingly prioritized ties with India and other rising Asian powers. The shift, which begun under King Abdullah (2006-2015) and accelerated under the current monarch King Salman, coincided with the fracking boom and the decline of U.S. oil imports, along with the increase in demand for energy in China, India, and other Asian countries.

A crucial driver of this shift in policy was Vision 2030—the plan of King Salman’s son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), to reform the Saudi economy and society by endings its dependence on oil exports and expatriate labor, including workers from Asia. In its place, the plan aims to promote a variety of industries where Asian investment and/or participation are critical: E-commerce, tourism, increasing the numbers of foreign participants in the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages, and providing logistical services to the fast-growing trade in the Middle East that is tied to Asia. Since the late 2000s, that trade and the need to secure it has prompted many of Asia’s leading governments to increase their diplomatic and military presence in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, potentially bringing Asia’s fiercest conflicts to Saudi Arabia’s shores. These geostrategic changes have nudged Saudi Arabia to further recalibrate its relations with the United States, Asia, and its neighbors in Africa and the Middle East.

Recent events have reinforced these trends. Although Washington and Riyadh worked to manage a crisis in world energy markets in spring 2020, the two governments have not found common ground in addressing Covid-19 and the global economic crisis that has accompanied the spread of the disease. Instead, Riyadh has solidified its partnerships with Asia. Not only did Saudi Arabia provide medical care, free of charge, to all foreigners in the kingdom, including undocumented immigrants, it also facilitated their evacuation from the country. Chinese and Indian doctors were welcomed to fight Covid-19. In May 2020, characters on a top Saudi television show and a senior member of the royal family signaled that Riyadh was open to warmer ties with Israel—an American ally and, importantly, a nation with deepening ties with both China and India. That same month, Riyadh bought $265 million worth of Covid-19 testing kits from BGI, a Chinese company that U.S. officials have negatively compared to Huawei. Following the deal, which was finalized on a telephone call between King Salman and China’s President Xi Jinping, a spokesperson for the Saudi Royal Court told Bloomberg that the purchase “confirms the strength of long-standing Saudi-Chinese ties.”

Section Two

Economic & Energy Ties

Saudi Arabia’s deep economic ties with China, India, and other Asian states emerged in the three decades after the end of the Cold War. During that period, declining U.S. imports of Saudi oil and exponential growth in oil imports in Asia’s largest countries reoriented oil markets and Riyadh’s outlook. While the United States imported more than 2 million barrels a day of Saudi petroleum in spring 1991 and spring 2003, it imported 335,000 barrels of Saudi oil in November 2019—thanks in large part to the revitalization of the U.S. oil industry after the introduction of shale oil-drilling techniques. By contrast, in 1993, three years after Riyadh and Beijing first formalized diplomatic ties, China became, for the first time, a net importer of oil, transforming it into one of Saudi Arabia’s top trading partners. In 1999, China and Saudi Arabia signed a strategic energy cooperation agreement, opening the door to a significant increase in bilateral trade.

Over the next two decades, based on data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Saudi-China trade rose from $1.8 billion annually to $59.4 billion, fueled by China’s economic growth and a steep rise in China’s daily oil imports. The rise in oil imports had, by 2017, propelled China into the role the United States had held for many decades—the largest oil importer in the world, making access to China’s oil market an economic imperative for Saudi Arabia. By 2019, China’s oil imports had risen to almost 10 million barrels of oil a day, the largest share of which, or 1.7 million barrels a day, was Saudi, an increase over imports in 2018. Following the economic dislocation caused by Covid-19 and a “war” with Russia over world oil prices in April and May 2020, Saudi Arabia, through deep discounts on its oil, increased its supplies to China to 2.2 million barrels a day—the most it had ever sold to the country and nearly a third of its total crude oil exports in May 2020.

Saudi Arabia's Energy Exports To Asia

Deepening Ties with South Asia

India had emerged as a valuable market for Saudi oil and gas as well. Because of its limited oil and gas supplies, India witnessed a surge in Saudi imports in the 1990s and 2000s, especially after free market reforms in the 1990s led to an economic boom. Between 1999 and 2018, Saudi-Indian trade swelled from $3.2 billion to $31.7 billion, much of which was oil exported to India. By 2015, India had become the third-largest importer and user of oil in the world behind only China and the United Sates—making it nearly as critical to Saudi Arabia’s future as China or Japan. In early 2020, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicted that India would overtake China as the world’s largest user and importer of oil by the middle of the 2020s. Five months after the EIA made that prediction, the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (ARAMCO), in May 2020, used discounts on oil to increase its market share in South Asia, helping Saudi Arabia overtake Iraq as the chief supplier of oil to India.

Significantly, those discounts built on Riyadh’s initiatives to enhance its ties with India in energy and in other fields, building on the $160 million that had been invested between 2015 and 2019. In 2019, ARAMCO announced that it would support a project to build a new $66 billion refinery in West India with a consortium of Indian companies. The project, which enjoys the strong backing of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, would add to India’s refining industry, the second largest in Asia after China. Further investments in the energy sector are expected to reach $100 billion. At the same time, nearly 480 Indian companies have invested $1.5 billion in Saudi Arabia and are contributing to major infrastructure projects, such as Riyadh’s Metro. In addition, Riyadh and New Delhi are developing an initiative whereby India will help the kingdom address its food security needs by providing essential foodstuffs—just as the kingdom helps provide India’s essential energy requirements. In May 2020, Ausaf Hussein, India’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, stressed the importance of the new partnership, noting that, already “75% of the basmati rice consumed [in Saudi Arabia] … is imported from India.”

For its part, Pakistan has also seen its trade with Saudi Arabia expand over the past twenty years, adding a key commercial element to a bilateral economic relationship defined by strategic military ties and expatriate workers. From 2000 to 2018, Saudi-Pakistan trade more than doubled from $1.5 billion to $3.7 billion, 90% of which are Saudi Arabia’s oil exports, thanks to Pakistan’s rapidly growing population and limited oil reserves. To aid Pakistan’s energy sector, Saudi Arabia announced that it would fund a $10 billion oil refinery in Gwadar, a port city in Baluchistan, an underdeveloped frontier region near Pakistan’s border with Iran. That city is a central piece in one of Beijing’s signature economic and political initiatives: the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a $62 billion project, announced in 2013, to upgrade Pakistan’s energy and transportation infrastructure while linking Western China to the outside world. When the project was announced, Saudi Arabia’s Energy Minister Khalid al-Falih stated that Riyadh intended it to benefit Pakistan’s and Saudi Arabia’s interests. “Saudi Arabia wants to make Pakistan’s economic development stable,” he explained “through establishing an oil refinery [in the city of Gwadar] and in partnership with Pakistan in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.” Equally important, by linking Saudi interests to the economic corridor, Riyadh also hoped to further link itself to China’s bold diplomatic and economic plan—the One Belt and Road Initiative (OBOR), which aims to use a variety of development and infrastructure investments to connect dozens of countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

Strengthening Economic Ties with ASEAN and the Tigers

Now titled the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi Jinping’s signature initiative has posed serious strategic challenges and opportunities to other Asian states that also saw bilateral trade and investment booms in recent decades. Saudi companies had invested $1.2 billion in Indonesian telecoms and other businesses by 2012. In 2009, Al-Rajhi Bank, one of Saudi Arabia’s largest banks, established a regional office in Malaysia, investing in its Islamic finance markets, the largest in the world in 2018. In 2017, ARAMCO entered into a $7 billion joint refinery agreement with Petronas, Malaysia’s state oil company.

Singapore, a city-state of 5.6 million adjacent to Malaysia, has consistently seen bilateral trade with Saudi Arabia increase, surpassing Saudi Arabia’s bilateral trade with France, a nation of 67 million people. In 2018, Saudi-Singapore trade was $12.4 billion, well above Saudi trade with France at $9.15 billion. The trade built on Singapore’s role as the principal oil refiner in Southeast Asia, as well as common financial ties. Singaporeans are some of “the most active investors” in Saudi Arabia, whose assets there were the fourth largest by value in 2017. Even more important than either oil or financial ties is the city-state’s geography: Singapore is the most strategically important port in the Straits of Malacca—the 500 mile (804 kilometer) waterway that links the Pacific and the Indian Oceans and serves as the principal transit point for oil traveling via sea from Saudi Arabia to East Asia.

Besides China, the two Asian countries that depend the most on the straits are Japan and Korea, highly developed economies that are dependent on oil and gas imported from the Middle East. Although Saudi Arabia has been the top supplier of oil for both countries for decades, their trade relationship also blossomed after the 1990s—just as Saudi Arabia’s trade with China and South Asia accelerated. While Saudi Arabia’s trade with Japan grew from $10.2 billion in 1999 to $38.15 billion in 2018, the kingdom’s trade with South Korea grew even more—from just $6 billion in 1999 to $30.4 billion in 2018.

To reinforce its economic relationship with both countries, Riyadh has followed a two-pronged strategy. It has invested billions in both countries’ economies, including a $45 billion investment in 2018 in Japan’s Softbank’s Vision Fund and, in 2019, more than $8 billion in a series of Korean petrochemical and propylene companies. These Saudi investments built on ARAMCO’s previous investments, dating back to the early 1990s, in Japan’s Showa Oil along with Korea’s S-Oil, one of Korea’s largest oil refiners. Over the past fifteen years, ARAMCO has also increased its stakes in S-Oil to 65% and in Showa to 14%, making the Saudi oil company the second-largest shareholder in Idemitsu Kosan, Japan’s second-largest oil company, which absorbed Showa in 2019.

Within the kingdom, Saudi officials and prominent trading families have partnered with prominent Korean and Japanese companies—a process reinforced by the leaders of the two Asian countries. South Korea’s President Lee Myung-bak, who was involved in projects in Saudi Arabia when he was an executive for Hyundai, marketed his country to the kingdom while he was president between 2008 and 2013. Major South Korean tech companies have benefited from his work, as have construction firms, winning major infrastructure products. For instance, Samsung C&T in 2013 won a $1.97 billion contract to build part of the Riyadh Metro. For their part, Japanese leaders, who also frequently visit the kingdom, have competed to retain Japanese companies’ role in the economy. For years, Japan has been an important investor while Toyota has been a market leader in new auto sales. Still, Toyota’s market share in the first quarter of 2020 was 29%, among its lowest in years, as automakers from other countries, including China, have rapidly gained market share.

Saudi's Top Trade Partners

A Comprehensive Economic Partnership with China

China is by far Saudi’s most critical economic partner. With the rise of China’s position in global energy markets, Saudi Arabia has recognized the need to form close ties with China’s energy companies, its refining industry, as well as its oil distribution and retail sales companies. Consequently, ARAMCO signed a series of partnerships with defense conglomerate Norinco; Zhejiang Petrochemical, an energy company; and Sinopec, the world’s largest oil, refining, gas, and petrochemical conglomerate. ARAMCO is also administering joint ventures in China with Sinopec and ExxonMobil. Since 2015, ARAMCO and Sinopec have run an oil refinery in Yanbu, a Saudi port city on the Red Sea coast. The Yanbu refinery was Sinopec’s first project outside China, paving the way for it to build other facilities, including the largest refinery in the Middle East: a state-of-the-art facility in Al-Zour in Kuwait near the country’s border with Saudi Arabia. In addition, China has cooperated closely with Saudi Arabia over the past decade to expand its domestic nuclear power program.

There has been a steady maturation of Saudi-Sino economic ties beyond energy. One of the most important new industries involved in the commercial relationship is infrastructure. Huawei, one of China’s most recognizable global brands, proved, in the 2000s, that its equipment could provide advanced cell phone service (a) to the remote mountainous regions of Saudi Arabia and (b) to the Hajj pilgrimage, where cell phone traffic grew to 19 times more than normal in Mecca because of the presence of millions of pilgrims. In 2009, the Saudi and Chinese governments agreed, for the first time, to cooperate on a joint economic project: a $1.8 billion special Mecca railway to facilitate the Hajj. In 2010, after China Railway Engineering Corporation successfully finished the project in Mecca, the Saudi government asked Chinese firms to build the Haramain High-Speed Railroad, the Mecca Metro, an expansion of King Khalid University, and multiple other industrial facilities.

While these projects enhanced bilateral ties, they also served a bigger strategic purpose for Beijing analogous to what the Yanbu oil refinery had meant for Sinopec—namely, they showed Saudi Arabia’s neighbors in Africa and the Middle East that Chinese companies could build the types of infrastructure projects that were essential to their economies along with the OBOR. The Mecca railway was in fact the first railway China had ever built in the Middle East. Today, ten years after the completion of that project, Chinese firms are building major infrastructure projects in virtually all of the kingdom’s neighbors in the Middle East and Africa.

These Chinese infrastructure projects are a key part of Vision 2030, the crown prince’s plan to reform Saudi Arabia’s economy and its society while reducing its traditional dependence on exporting oil. In remarks introducing Vision 2030, MbS addressed the cyclical nature of state spending under the current system and the danger it poses to the country: “We have developed a case of oil addiction in Saudi Arabia.” In the future, the prince continued, “we will not allow our country ever to be at the mercy of commodity price volatility or external markets.” Though measures linked to women driving, the opening of movie theaters, integrating more Saudis into the private workforce, and the ARAMCO initial public offering have made headlines worldwide, other parts of the plan, which specifically look to Asian nations, have garnered less attention.

Saudi policymakers expect that China, as part of BRI, as well as other Asian powers will invest in two other central parts of Vision 2030—namely, new Saudi e-commerce companies, which will use Huawei equipment, and logistical and transportation hubs modeled on the success of Dubai. In particular, the Saudi hubs seek to take advantage of the country’s eight international land borders along with its 1,640 mile (2,640 km) coastline, both of which provide access to a vast geographic area: more than 15 countries in Africa and the Middle East along with key strategic waterways. While many of those countries have benefited from significant investments from China, the waterways are even more significant, for they are the central arteries of twenty-first-century global trade connecting Asia’s economic powers with their energy suppliers in the Middle East and their principal markets in Europe.

Section Three

Strategic & Diplomatic Relations

Taking advantage of the new strategic opportunities created by Asia’s rise will require Riyadh to reconceptualize its strategic and diplomatic relationships, especially since Asia’s great powers and its major Muslim nations have generally not supported the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen starting in 2015, the Qatar blockade, or Riyadh’s hostility toward Tehran. As Saudi leaders navigate this new dynamic, they can build on 15 years of diplomacy dedicated to expanding the country’s ties to Asia. When King Abdullah ascended to the throne in 2005, he signaled his commitment to a new “look east policy” by making his first trip as monarch outside the Middle East to four Asian nations: China, India, Malaysia, and Pakistan. On the trip, which took place in 2006, the king became the first Saudi leader to visit India since the 1950s and the first Saudi leader ever to visit China. A decade later, after Donald Trump entered the White House in 2017, King Salman, Abdullah’s successor, visited Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan, and China in February before traveling to meet Trump in the United States.

SAUDI ARABIA-ASIA BILATERAL VISITS AND JOINT EXERCISES

Managing Friends New and Old

When Salman made that trip, he and other Saudi officials were signaling their commitment to deepening diplomatic ties with China and other Asian powers, even if those ties conflicted with Washington’s core goals. In 2014, Saudi Arabia became a founding member of the Beijing-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), an institution that is seen as crucial to the success of the BRI, which Washington opposes. As U.S. warships openly challenged China’s claims to the South China Sea and Washington pushed Southeast Asian nations to resist Beijing’s actions in Asian waterways, Saudi diplomats, in 2016, welcomed what they called “China’s adherence to peaceful means in settling disputes concerning the South China Sea.” Three years later, following U.S. criticism of China’s treatment of the Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, MbS, during a state visit to Beijing, refused to touch the matter, stating that “China has the right to take anti-terrorism and de-extremism measures to safeguard national security.” In global disputes involving Beijing and Washington, MbS has shown a willingness to defer to Beijing’s positions—acknowledging China’s position in Asia along with its “multifaceted and dynamic material footprint” across the Middle East.

Riyadh has shown a similar understanding of New Delhi’s growing power. Since the two sides signed the New Delhi Declaration in 2006, Riyadh has steadily prioritized ties with New Delhi over those with Islamabad, the kingdom’s traditional ally in South Asia, and has befriended the government of Prime Minister Modi. During Modi’s second term, Riyadh has not publicly criticized India’s controversial new citizenship law and anti-Muslim violence and New Delhi’s actions in Kashmir—a Muslim-majority region claimed by India and Pakistan, as well as a small section by China. In fact, ARAMCO announced plans to invest in a refinery in Gujarat a week after New Delhi, in 2019, revoked Kashmir’s special legal status, a decision that enraged Islamabad. In spring 2020, while the Human Rights Commission of the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC), a global Islamic organization based in Jeddah, issued a statement about Islamophobia in India connected to Covid-19, Riyadh did nothing.

Islamabad has sought to adjust to this new reality, retaining economic and strategic ties with Riyadh while expanding diplomatic ties with Beijing and Tehran. Although it refused to send forces in 2015 to help the Saudi military operation in Yemen, Pakistan subsequently deployed soldiers to the kingdom, including for the Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition (IMCTC), a Saudi-led military alliance of Sunni nations. In July and August 2020, the relationship grew especially tense when Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi criticized the OIC and, implicitly, Saudi Arabia about Kashmir, while Riyadh forced Islamabad to secure a $1 billion loan from Beijing to pay back a loan it owed to the kingdom. Eventually, Pakistan’s Army Chief of Staff General Qamar Javed Bajw was dispatched to Riyadh in late August 2020 to smooth over relations.

Managing Fraught Ties with Muslim Asia

Saudi Arabia’s ability to find common ground with China, India, and Pakistan contrasts with its diplomatic and strategic relationship with Malaysia and Indonesia. In Malaysia, the deep ties that Saudi leaders built during the nine years that Najib Tun Razak (r. 2010–2018) was prime minister became a burden when Mahathir Mohamad defeated Najib in the 2018 elections—thanks in part to the accusations of corruption tied to 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), a development bank that allegedly received contributions from prominent members of the Saudi royal family. After the elections, Muhammad Sabu, the new Malaysian defense minister, withdrew Malaysia’s forces from Saudi Arabia, where they were aiding Saudi operations in Yemen, while Mahathir built closer ties to the kingdom’s chief rivals in the Middle East. At the Kuala Lumpur Summit, held in December 2019, Mahathir and the leaders of Iran, Qatar, and Turkey sought to create a new institution to lead the Muslim world to challenge the role played for decades by the OIC. Although Saudi-Malaysian relations have improved after Muhyiddin Yassin became the prime minister in March 2020, with Riyadh donating personal protective equipment to Kuala Lumpur in May 2020, neither 1MDB nor the events of the Kuala Lumpur Summit have been forgotten. Mahathir and his colleagues failed to achieve their goals in Kuala Lumpur because Saudi Arabia successfully pressured Pakistan to not attend the summit while Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo withdrew because of personal exhaustion. That decision contrasted with Jakarta’s choice to be neutral in the war in Yemen, call for dialogue in the Qatar dispute, and its refusal to join the IMCTC. Those choices, in part, prompted King Salman, in 2017, to make the first visit by a Saudi monarch to Indonesia since 1970. While he did not address concerns about the treatment of Indonesian workers in Saudi Arabia, he announced significant investments, attended interfaith meetings, and exchanged handshakes and took pictures with women. Together, these actions helped counter a perception among some Indonesians that Saudi Arabia is a closed nation hostile to the contemporary world.

Saudi Ambassador Esam Althagafi has reinforced this message. Appointed in 2019, he has said that Indonesia “is a member of Vision 2030,” broadening bilateral ties to include economic and socioreligious components. The latter has been a divisive topic for decades, with the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Muslim organization, challenging the vision of Islam promoted by Saudi Arabia. Mindful of these criticisms, Althagafi has sought to reframe Saudi Quranic competitions, educational exchanges, and other activities as analogous to the cultural activities carried out by the British Council and the Alliance Française. His language has also implicitly downplayed the influence that Riyadh could wield over Indonesia’s domestic and foreign policies—as a result of its control over the numbers of pilgrims who can go on Hajj and Umrah. Still, Ma’ruf Amin, the NU’s longtime spiritual leader, became vice president in 2019, further complicating Saudi Arabia’s diplomatic ties with the world’s largest Muslim nation.

Competing for Asian Friends in a Divided Region

The multifaceted factors shaping Riyadh’s dealings with the Muslims of Southeast Asia provide a framework to understand the diplomatic and strategic forces that have been set in motion by the rise of Asian powers in the Middle East. On the one hand, Asian powers desire warm ties with Saudi Arabia and are willing to show deference to Riyadh at sensitive moments. In January 2016, President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia shortly after the kingdom’s execution of a prominent cleric had set off a fierce diplomatic conflict between Riyadh and Tehran. As P.R. Kumaraswamy and Md. Muddassir Quamar have noted, India has chosen “to elevate and intensify ties with the Kingdom” despite “increasing western criticisms of Riyadh’s foreign policy choices and concerns over human rights records.” While most Western leaders publicly shunned MbS at the G20 summit in 2018 in Argentina after Jamal Khashoggi’s murder, Modi, breaking protocol, publicly embraced him upon his arrival to India in February 2019. In June 2019, Korean President Moon Jae-in hosted MbS in Seoul and signed multiple agreements with him—only a week after the United Nations released a report linking the Saudi government to the killing of the Saudi journalist. India also refrained from commenting publicly on Khashoggi’s death.

On the other hand, Asian leaders’ vision of the Middle East is more expansive than that of Saudi leaders. Modi’s “Look West Policy,” for instance, seeks to build firm ties with Saudi Arabia and other countries in the region that Riyadh sees as hostile. While Saudi Arabia views Iran as a key source of conflicts in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, Asian governments have remained officially neutral in these conflicts. As they have courted Riyadh, Beijing and New Delhi have deepened their military ties with Tehran, with Beijing, in July 2020, proposing a 25-year economic and security partnership with Tehran. China and India have also joined other major Asian and European global powers in backing the Iranian nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), an agreement that Riyadh and Washington view as a threat to regional peace. For instance, when a U.S. airstrike killed Qasem Soleimani in January 2020, Beijing praised Tehran for its restraint while pledging “relentless” diplomacy to salvage the JCPOA—“an important pillar,” in Beijing’s eyes, “for global nuclear non-proliferation and peace and stability for the Middle East.” In addition, Beijing and New Delhi have retained their links with Doha after Riyadh launched a regional boycott of its neighbor in 2017, with the Indian and Qatari militaries conducting joint military exercises in November 2019.

Although China, India, and Saudi Arabia support the Palestinians, China and India have, in recent years, intensified their ties with Israel, a country that has no diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia. Israel is India’s third-largest supplier of weapons, while Beijing has growing investments in high-tech industries ($16 billion) and construction ($4 billion) in Israel. In addition, a Chinese firm will run the Port of Haifa in 2021, and another Chinese firm is building a terminal for the Port of Ashdod, one of Israel’s two main cargo ports. Importantly, some Israeli officials and academics see these growing ties as part of a process that will also improve Israeli ties with Saudi Arabia. In their chapter on Saudi Arabia’s ties with Israel in Fraternal Enemies: Israel and the Gulf Monarchies, Clive Jones and Yoel Guzanksy cite Dore Gold, a former director of the Israeli Foreign Ministry as saying, “The United States will not be the foremost country in coming years, for China will challenge it with its well-known strategic project: the Silk Road.”

Saudi Arabia has responded to this changing regional dynamic in much the same way that Israel has: it has sought to retain its traditional diplomatic positions, including military ties with Washington, while taking small but significant steps to accommodate the interests of Asia’s large powers and other states. As Hesham Alghannam, a senior fellow at the Gulf Research Center, has noted, Riyadh does not wish to replace one “ally with another”—instead, it seeks to balance the great powers through new diplomatic frameworks. After the assassination of Soleimani, Riyadh followed a strategy analogous to the one that Alghannam had laid out: it worked to ease regional tensions, stressing its support for Washington but adding that it had not been consulted on the strike. That cautious approach continued in the multilateral diplomatic response, including closely working with the United Nations, which Riyadh employed after the drone attack on its massive oil refineries at Abqaiq and Khurais in September 2019.

A More Nuanced Approach to Israel

Saudi Arabia has pursued a similar strategy with Israel, seeking areas of common interest while retaining its public support for the Palestinians, a central component of its claim to leadership of the Arab and Muslim worlds. Although Riyadh has strongly warned against Israeli plans to annex Palestinian territory and stressed the need for Israel to reach a comprehensive peace agreement with the Palestinians before relations could be normalized, Saudi officials met with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 2019 to discuss containing Iran. Salman al-Ansari, a Saudi living in America, even suggested in a column published in The Hill that Israel could assist with Vision 2030. In April 2020, Haaretz reported that Blue-Raman Google’s proposed fiber optic cable connecting Italy and India, would likely transit Israel and Saudi Arabia, using a route across the kingdom analogous to that followed by Air India 139. In May 2020, characters debated normalizing ties with Israel on a popular Saudi TV show, while Prince Khalid bin Salman, MbS’s brother, reportedly told a U.S. rabbi that Israel was integral to Vision 2030 and that there was no barrier to the normalization of ties once Israel and the Palestinians had achieved a just two-state solution. Although some viewed the statement as a blunder, it was consistent with Riyadh’s strategy of balancing a commitment to the Palestinians with pursuing common goals with Israel—a nation whose expanding ties to China and India have made it an increasingly valuable potential regional partner. Nor is this strategy inconsistent with past Saudi policy: As Abdulaziz Alghashian notes in a fascinating recent Ph.D. dissertation, the Kingdom’s approach to Israel has long been defined by nuance, often reflecting the various forces shaping its regional and global policies.

The nuanced nature of the Saudi position toward Israel was made even more complicated in August 2020 when President Trump announced that Israel had entered a deal that would lead to the full normalization of its diplomatic relations with the United Arab Emirates—another nation with deepening ties to China and India, both of which praised the deal. Although the Saudi government initially made no statement about the agreement and hashtags attacking it trended in the Kingdom, Riyadh soon after permitted, for the first time, an Israeli airliner to use Saudi airspace. Within days of that flight, the first between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, Faisal bin Farhan, tweeted that flights “from all countries” could transit the Kingdom’s airspace on trips to the Emirates. While the Saudi foreign minister stressed in the same tweet that Riyadh continued to support the Palestinians and the Arab Peace Initiative, most commentators saw the decision as an historic change, with a Bloomberg headline stating that “a 72-year taboo” with Israel had been broken. In mid-September 2020, Manama, which has deep political and economic ties to Riyadh, announced that Bahrain also would normalize its relations with Israel. It is unlikely that Bahrain’s monarch, Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, could have acted to improve ties with Israel without Saudi consent.

Lost in these headlines about the UAE and Bahrain was the role of Asia in the normalization for Saudi Arabia and for its partners. Not only were Farhan’s words of support for the Palestinians aimed, in part, at appeasing vast Muslim audiences in Asia, but he and his colleagues could not overlook the fact that both Beijing and New Delhi supported the U.S.-brokered deals. Emiratis and Israeli planners also see the opening of Saudi airspace to Israeli and Israeli-bound aircraft as essential to their future economic ties with Asia. Israelis will be able to travel—via Saudi Arabia—directly to Asia, while “Emirati ‘super connectors’ Etihad and Emirates” will be able to serve Asian business travelers, who have had to transfer in either Europe or Turkey on their way to Israel. In the eyes of several analysts, those growing economic and political ties with Asia, especially with China, may have been a significant factor in motivating the Trump Administration to push for an agreement between Israel and the Emirates.

Ultimately, how Riyadh continues to respond in the long run to the UAE-Israel agreement and the normalization of Bahrain’s ties with Israel will not only provide a decisive test of its relations with Washington and Abu Dhabi but also reveal just how much China’s and other Asian nations’ emergence has transformed the diplomatic landscape for Saudi Arabia and the wider region.

Section Four

Security & Military Cooperation

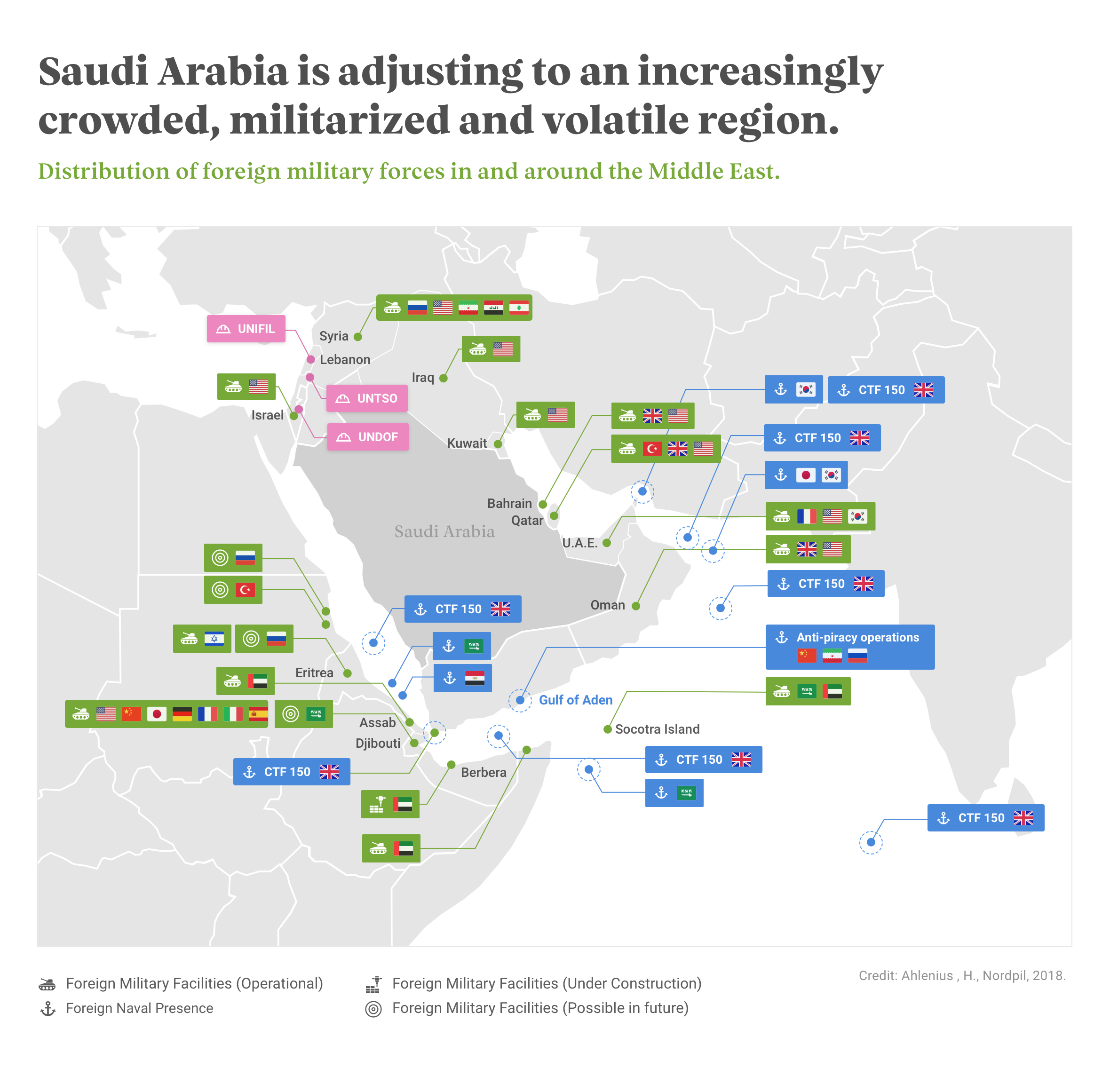

The UAE’s diplomatic agreement with Israel could further complicate the regional military balance for Riyadh—one in which conflicts in the Gulf, the Levant, and Yemen must be considered alongside new ones in the Red Sea. There, international naval operations against Somali pirates and Beijing’s growing presence in East Africa and the Red Sea have created a zone of potential conflict adjacent to Saudi Arabia’s 1,100 mile (1,760 km) western border. While Iran and the alliance with the United States remain essential factors for Saudi security planning, the role of China and other Asian powers is also now part of the kingdom’s strategic calculations. Indeed, Mohammed Alsudairi, a scholar at the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, Saudi Arabia’s leading research center, noted in January 2020, “the People’s Republic of China … has emerged over the past decade as one of the most important and decisive actors in both the Arab world and Africa writ large.”

A Crowded and Volatile Region

One can see the wisdom of Alsudairi’s observation in the Red Sea. There, China’s opening of a naval facility in 2017 in Djibouti, an East African country 370 nautical miles (684 km) from the coast of Saudi Arabia, sparked particular concern among world powers, compelling many to increase deployments in the Red Sea. In 2020, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States, all of which had bases in Djibouti before China did, operated military forces in the Red Sea region alongside those of a host of other nations: China, Egypt, European Union states, India, Iran, Israel, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. In the eyes of India and Japan, their deployments in the Red Sea and the surrounding regions are key elements of their geopolitical strategies to check China’s rising naval power in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, security analysts see the Djibouti base as “the first of a network of Chinese bases across” the Indian Ocean to surround India.

In response to this changing regional and international dynamic, Riyadh has sought to build a base in Djibouti to supplement the UAE base there (set up for the war in Yemen) and its existing bases in the western regions of the kingdom. Saudi officials, in January 2020, also spearheaded the formation of the Council of Arab and African Coastal States of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden (CAACSRA).

In a report for Riyadh’s King Faisal Center, Alsudairi stressed that the kingdom’s policymakers needed to use CAACSRA to create a dialogue between China and the region’s other key stakeholders. To address the new dynamic created by China’s rising power, Alsudairi argued that CAACSRA should promote a set of maritime protocols for the navies operating in the region. These protocols, he explained, could reduce “the risk of confrontations” while protecting the “vital maritime passageway from being impacted by other … external conflicts happening elsewhere in the globe.” By making this argument, Alsudairi was also subtly making a larger point: the presence of many rival navies in the Red Sea risked involving Saudi Arabia in conflicts in Asia and elsewhere that had little or nothing to do with the kingdom’s interests.

The Dangers of Great-Power Competition

The dangers of great-power competition in the Red Sea that Alsudairi highlighted help us see how Asia casts a shadow over the kingdom’s military ties in the region and its ties with other powers, especially the United States. For years, the United States has been one of Saudi Arabia’s principal suppliers of advanced weapons, with the kingdom becoming the top market in the world for U.S. weapons between 2013 and 2017. In fact, the Royal Saudi Force maintains the third-largest fleet of the U.S.-made F15 fighter aircraft in the world after the United States and Japan. Even after Riyadh implemented unprecedented budget cuts in May 2020 in response to a drop in oil prices and the Covid-19 economic crisis, it continued to buy U.S.-made weapons—a decision that has helped maintain the long-standing ties between the two countries, whose interests and institutions align well. The U.S. military sees Iran as a central threat to the Middle East and has a strong foothold in the waterways surrounding the kingdom and those connecting it to Asia.

But the Sino-U.S. rivalry in Asia over the past decade and the Covid-19 epidemic present serious challenges to the military alliance, which has been the cornerstone of Saudi security policy for decades. First, the Sino-U.S. rivalry, which has intensified during the Covid-19 epidemic, risks drawing Riyadh into a dangerous global conflict, where Beijing could, in a crisis, replace Saudi oil imports with Russian or other oil imports.

Second, the Sino-U.S. rivalry and, now, the Covid-19 epidemic have refocused American politics and national priorities away from the Middle East and Saudi Arabia. Although Barack Obama and Donald Trump are “diametrically unlike each other,” both men pledged, as candidates for the presidency, to reduce the nation’s military commitments in the Middle East while refocusing U.S. priorities to Asia—promises that they both fulfilled while in the White House. Trump, who has been criticized for his ties to MbS and his refusal to criticize the Saudi crown prince, has used harsh rhetoric against the Saudis in public and private settings. In 2015, he accused them of “freeloading” on American military power, while in 2019 he asserted that America was “losing its shirt defending Saudi Arabia.” In spring 2020, Trump threatened to withdraw U.S. military protection from Saudi Arabia unless the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) agreed to his demands to reduce its oil production. While that dispute was resolved without Trump carrying out his threat, soaring U.S. budget deficits in 2020 because of the Covid-19 crisis have forced his administration to prepare for future cuts to the Pentagon’s budget, including to its overseas military commitments.

Should Washington withdraw some of its military commitments to Riyadh, could another country provide Saudi Arabia with the security guarantees that the United States now does? Russia and Turkey are already aligned militarily with Iran and Qatar, respectively, both of which are Saudi regional rivals. By contrast, the great powers of Asia have significantly greater potential power projection capabilities than either Russia or Turkey but are also not ideal alternatives to the United States—in large part because of the politics of their home region and their own interests in the Middle East.

A good example is India, whose navy can project power into the sea-lanes through which 75% of Saudi oil supplies head to East Asia. India also maintains military bases throughout the Indian Ocean from East Africa to Southeast Asia, has naval experience in the waterways near Saudi Arabia, and conducts joint patrols with the navies of Australia and multiple Southeast Asian nations. In 2019, Indian and Saudi officials announced that their navies would carry out joint exercises in the next year to protect both “the security and safety of waterways in the Indian Ocean and the Gulf region”—a task that many Saudis had once assumed that only the U.S. Navy could carry out. Still, a military alliance with New Delhi risks drawing Riyadh into the simmering Sino-Indian tensions and could be complicated by India’s large population of Shi’a Muslims and past initiatives to deepen strategic ties with Iran, such as developing the Chabahar Port. Regardless, it is far from clear that India has the capability or will to play a larger security role in the region. Moreover, India has not always supported Saudi’s interests within the region, opposing its positions in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

The two other major powers in Asia, Japan and China, operate navies in many of the same strategic waterways that India does and would complement the kingdom’s military capabilities in different ways. Japan employs many of the same U.S.-made weapons that the kingdom does and works closely with the U.S. military. Beijing, by contrast, has sold Riyadh weapons, such as missiles and armed drones, that Washington had refused to provide to the Saudi military before July 2020. Those sales built on Saudi-China military ties dating back to the 1980s—when Riyadh purchased CSS-2 missiles from Beijing—along with recent joint military exercises. Both the Chinese and Saudi militaries also have long-standing ties to the Pakistani army, which has deployed its forces to the kingdom and uses U.S.-made weapons. Even if China cannot project the same type of military power that Washington can in the Gulf today, it is assumed among many Saudis that it will be able to do so in the future. As Alghannam has observed, it is “inevitable” that Riyadh’s economic ties with Beijing will expand to include a strong military component. At the same time, deeper military ties with either Beijing or Tokyo risk dragging Riyadh into the complicated politics of Asia and into a set of partnerships where Tehran also has some sway. In December 2019, China, Iran, and Russia conducted a joint naval drill in the Gulf of Oman.

Should Riyadh sign a military treaty with Beijing or substantially increase its purchases of Chinese weapons, Washington would also likely limit Riyadh’s access to the spare parts needed to operate its U.S.-made weapons. In June 2020, U.S. Central Command General Kenneth McKenzie warned that China’s presence in the Middle East was a “significant factor that we need to confront.” Since Khashoggi’s murder, there have been repeated bipartisan calls in the U.S. Congress to curb military sales to Riyadh, calls that would grow louder should Riyadh ally with Beijing.

Section Five

People-to-People Ties

A key but understudied part of the burgeoning Saudi-Asia relationship is the deep cultural ties that bind the Kingdom to Asia in the twenty-first century. The flow of people from Asia to Saudi Arabia is a key driver of this cultural exchange with countless Asian pilgrims and migrant workers flocking to Saudi Arabia every year.

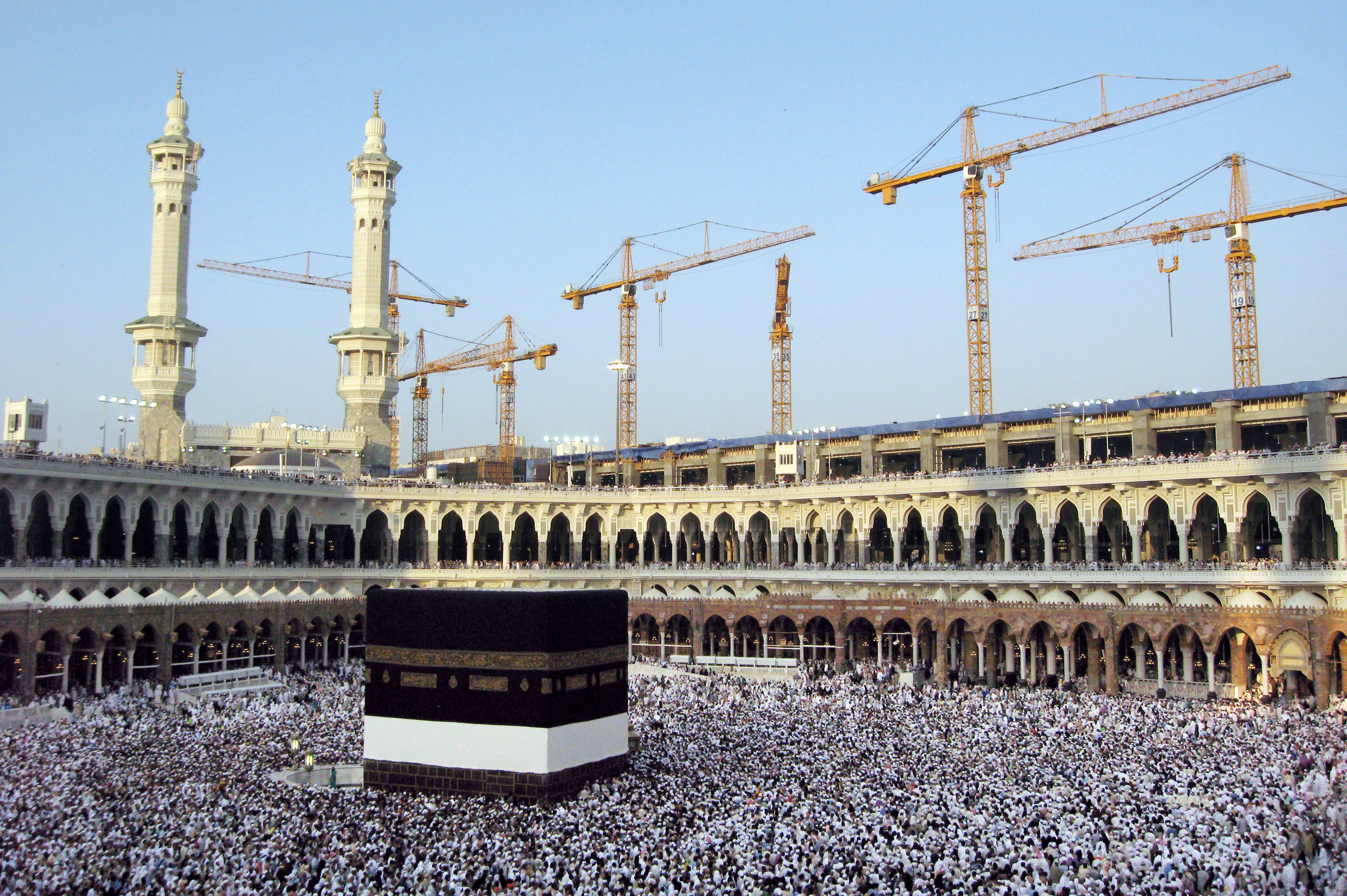

Building Ties Through Pilgrimages

Two of Saudi Arabia’s most important cultural linkages to Asia are the Umrah and Hajj, many of whose participants are from Asia. Since 1986, Saudi kings have reinforced that linkage by referring to themselves as the “Custodians of the Two Holy Mosques”—or the two holiest mosques in Islam: the Al-Haram Mosque in Mecca and the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. Pakistan, Indonesia, India, Malaysia, and Bangladesh send the largest number of pilgrims from Asia, with Indonesia alone contributing more than 220,000 pilgrims a year to the Hajj and 100,000 a month for Umrah. The Hajj also plays a key role in Saudi diplomacy, with MbS, in February 2019, acceding to Modi’s request to raise India’s annual Hajj quota by 25,000 to nearly 200,000—the third increase in three years.

Vision 2030 identified opening the kingdom to tourism while increasing Mecca’s and Medina’s capacity for Hajj and Umrah as an important objective. These plans recognized the pent-up demand among tourists to see the kingdom, an exotic locale, and the desire of 1.8 billion Muslims worldwide to undertake the Hajj pilgrimage—one of the five pillars of their faith. The latter demand is vast in Asia, where it can take 15 years or longer of waiting and the equivalent of a lifetime’s savings to secure a visa to join one of Asia’s national delegations for the Hajj. According to Saudi official statistics, 75% of the 2.49 million pilgrims who participated in the 2019 Hajj came from overseas, while about 40% of the 19 million Umrah pilgrims in 2019 were from overseas. By 2030, Riyadh aims to host at least 30 million Hajj and Umrah visitors, an expansion that is expected to increase Hajj and Umrah revenues to at least $13.2 billion a year. Saudi economists hope that the pilgrimages will be a $150 billion industry, potentially enough to fund “the entire national economy.”

Non-Saudi Hajj Pilgrims by Region

The Threat of Covid-19

In 2020, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and other nations in Asia canceled Hajj plans weeks ahead of Riyadh’s announcement that no one from outside Saudi Arabia would be permitted to perform the pilgrimage that year because of Covid-19. Still, Riyadh mandated that 70% of the 1,000 pilgrims permitted to go on Hajj in 2020 were non-Saudis. They underwent vigorous screening before they were permitted to join the Hajj, quarantined before and after the pilgrimage, and adhered to a plethora of safety protocols while in Mecca and Medina.

Those precautions reflected the fact that the virus had already spread in Saudi Arabia, especially in the labor camps and immigrant neighborhoods in the kingdom’s western region. By early May, expatriate workers, including those expanding Mecca’s Grand Mosque, made up as much as 70% of Saudi Arabia’s Covid-19 cases. As Eman Alhussein has noted, few parts of the country were more impacted by the virus than Al-Nakkasah—a densely populated and poor area of 200,000 Burmese and Bangladeshis in the center of Mecca, a short distance from the Kaaba.

Neighborhoods like Al-Nakkasah house the enormous Asian community in the kingdom. Many of these Asian groups settled in Saudi Arabia after performing Hajj or Umrah, while others came to study or work, especially during and after the oil boom in the 1970s. Despite attempts to bring more Saudis into the economy as part of Vision 2030, Asians and other foreigners accounted for 77% of the Saudi workforce in 2019. A year earlier, in a country of almost 34 million people, there were at least 1.54 million Indians, 1.06 million Pakistanis, 826,777 Bangladeshis, 708,666 Filipinos, 649,611 Sri Lankans, and 472,444 Indonesians. These workers send vast sums home as remittances—$9.28 billion to India alone in 2018—that have helped alleviate poverty and spurred development across Asia for decades.

Those remittances, however, are likely to be significantly altered, due to the spread of Covid-19. In spring 2020, Riyadh imposed a strict lockdown throughout the kingdom and sealed international borders to control the virus. While Riyadh extended the expired visas of foreigners and provided medical care free of charge to them, many workers went unpaid for extended periods, leaving them without a way to provide for themselves. For weeks, the social media accounts of Asian embassies in Riyadh were filled with emergency appeals for food and medicine. At the same time, Saudis pressured businesses to lay off foreign workers, whose dominance of the workforce, Khaled al-Oqaily, a popular talk show host, stated was “a real danger” to the nation. It was “the national duty” of Saudi businesses, he added, to “lay off foreign rather than local employees.”

This type of rhetoric has had an effect. The government, as part of its national strategy to address the losses businesses suffered because of the lockdown, pledged to help firms cover the salaries of Saudi workers but not foreigners. In April, Riyadh launched Awdah (“Return”), a program that provides foreigners, regardless of their legal status, an online procedure to quickly get a visa to go home. Once the visa is approved, workers are expected to make arrangements to leave. Riyadh’s willingness to allow workers who are out of visa status to apply for the program was critical because it removed an impediment for departure in a country where foreign workers are routinely cited for violating labor, residency, and border security laws.

By early June 2020, almost 180,000 people had registered with Awdah, while 12,798 had already left the country, many on the flights provided by the Saudi government or through programs such as Vande Bharat (Glorious India), New Delhi’s project to repatriate its citizens stranded overseas. By July 2020, Jadwa Investment estimated that 467,000 expatriate workers had already left the Saudi labor market. When international commercial air travel resumes, more will leave, with at least 1.2 million foreigners expected to depart by the end of the year. Some Bangladeshis and Pakistanis in Saudi Arabia and its Gulf neighbors have already started to send funds home in preparation for a permanent return to their home countries. Even some professionals, who had the resources to survive the lockdown, are also considering leaving the country permanently due to (a) the deteriorating state of the Saudi economy and (b) plans, expected to be implemented by August 2020, where Saudis will fill 70% of the positions in retail and wholesale in industries ranging from coffee to toys—many of which expatriates have dominated for years. Ultimately, Riyadh hopes that these positions will help reduce unemployment among Saudi nationals.

These changes will have sweeping effects in the kingdom and Asia, beginning with a ballooning budget deficit ($29 billion in the second quarter of 2020) and a 4% fall in the country’s population in 2020. That decline, which is driven by an exodus of workers to Asia, could negatively impact government finances by decreasing the amount of money that Riyadh will collect from both the value added tax (VAT) and the fees it imposes on foreign workers and their employers. In recent years, Riyadh has raised the VAT and those fees to offset declining oil revenues—with press reports, in late 2019, stating that Riyadh expected to net $17.33 billion alone in 2020 from the fees that Saudi companies would pay to employ foreign workers. The absence of workers and visitors from Asia has also decimated the Saudi culture, entertainment, and tourism sectors. Notably, Riyadh had hoped that these three sectors, all of which were part of Vision 2030, would help Saudi Arabia transition away from an economy dominated by energy. Finally, the Covid-19 economic crisis and recent government budget cuts have impacted many of the country’s most prominent businesses, such as the Bin Laden Group, which has reportedly not paid the salaries of many of its employees for extended periods in 2020.

The absence of those salaries will have a significant impact on India, the Philippines, and other middle- and low-income Asian nations that depend on remittances to balance their current accounts. In these countries, the World Bank expects that there will be a 20% or more reduction in remittances from Saudi Arabia and other states in 2020, by far the steepest decline on record. In Indonesia, the decline in remittances will be compounded by the country’s dependence on Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, which account for 43% of its overseas transfers. The most impoverished in Asia will likely bear the brunt of this crisis, particularly in the Philippines, where “three-quarters of poor households rely on remittances.” Nor will it be easy for returning workers from the kingdom, some of whom may have Covid-19: they will join “labor markets brimming with unemployed young people” while putting pressure on “already fragile public health systems.”

This dynamic will be acutely felt in Kerala, where it is said, “when the Gulf sneezes, Kerala catches a cold.” As Bobby Ghosh has noted, the Indian state has had “an unhealthy addiction to remittances” for decades and has not provided its citizens with viable “alternative opportunities.” Because of these choices and the impact of the Covid-19 crisis, Kerala’s economy is likely to contract by 10% in 2020, with the state’s finance minister, Thomas Isaac, expecting that “every sector” will be “devastated.”

Saudi Arabia’s Expatriate Population

Saudi’s Growing Cultural Sway

As bonds linking thousands of workers from Asia to Saudi Arabia begin to recede, other sociocultural ties between Riyadh and the rest of Asia have endured or even grown. In 2018, India was the “Guest of Honor” country at Janadriyah, an important annual Saudi cultural festival. Chinese and Saudi officials have sought to strengthen socioeconomic ties, such as introducing Mandarin into Saudi schools, a program that builds on the economic and cultural success of Huawei: the first Chinese company to receive a 100% commercial license to invest in Saudi Arabia, a major achievement in a country where most foreign firms have to work with a local partner. Huawei’s success in the kingdom rested on its ability to bridge deep cultural divisions while meeting the technical needs of its customers. In particular, the company has educated its Chinese staff about Arab culture and Islam while also devising work plans to address the cultural and religious needs of its local employees. Huawei also built a prayer hall for Muslims in the lobby of its corporate headquarters—a decision that greatly impressed a visiting delegation of Saudi business officials in 1999.

For their part, Saudi officials, private foundations, and a host of individual donors have worked to harness the kingdom’s considerable cultural power among Muslims to promote its diplomacy in China and the rest of Asia. Over the past four decades, they have funded Quranic reading competitions and other cultural events, madrassas, mosques, and new private and state universities in Asia. These institutions have had a significant impact on Islamic practices and norms in countries as different as Pakistan and Indonesia. In the latter, the College of Islamic and Arabic Studies, the branch campus of Riyadh’s Imam bin Muhammad University, has used free tuition, monthly allowances, and opportunities to study in Saudi Arabia to recruit promising Indonesian students. After completing their education, many of these students have worked “to expand the Saudi interpretation of Islam in Indonesia.”

Although that vision has at times faced steep cultural and institutional resistance, it has nonetheless shaped the contemporary politics and society throughout the vast archipelago. An important figure who has upheld this vision is Rizieq Shihab, a powerful sheikh, who leads the Islamic Defenders Front, an influential Indonesian Islamist organization. In 2016, he led an unprecedented demonstration of half a million people in central Jakarta demanding that Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (widely known as Ahok), who was governor of Jakarta and an ally of President Widodo, be tried for blasphemy. A year later, after Ahok had lost his bid for reelection, he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to two years in prison for blasphemy.

Shortly thereafter, however, Shihab was in Saudi Arabia, where he went on Umrah after Indonesian police accused him of violating pornography laws while also insulting the Pancasila, Indonesia’s state ideology. His presence there became a serious diplomatic flashpoint between the two countries in December 2018 when Osama bin Mohammed Abdullah al-Shuaib, then the Saudi ambassador to Indonesia, tweeted pictures of a rally of Shihab’s supporters with a caption that suggested that the NU was a heretical organization. The tweet, which was quickly deleted, enraged the NU, whose members called for his immediate removal as ambassador. Many Indonesians also saw the tweet as unacceptable meddling in their domestic politics and a reminder of the potential power that Riyadh could wield in the archipelago nation—thanks to its control over how many Indonesians go on Hajj, the hundreds of thousands of Indonesians who work in the kingdom, and Saudi linkages to educational institutions and to leading figures such as Shihab. Nor had it gone unnoticed that the only Indonesian public figure whom the Ambassador followed on Twitter was Prabowo Subianto, then a prominent political rival of President Widodo.

While there was no proof that Al-Shuaib was acting on behalf of his government and Althagafi soon replaced him as ambassador, the incident and the issues that it raised have not been resolved. Shihab remains in Jeddah—despite Althagafi’s statement in December 2019 that his government and Indonesia’s had discussed his status and hoped to reach a resolution in the near future. Because of both its wealth and geography, Riyadh retains a set of cultural and socioreligious tools that can influence Indonesia and other Asian nations with sizeable Muslim populations. While the power associated with these tools is rarely discussed, it is a tangible force that reinforces the kingdom’s position from the Arabian Sea to the Pacific Ocean.

Section Six

Conclusion

In her 2012 book On Saudi Arabia, Karen Elliot House argues that Saudi Arabia had “clearly shifted from a singular dependence on the United States to a more multipolar foreign policy”—a framework in which U.S.-Saudi relations were, in the words of former Saudi foreign minister Prince Saud al-Faisal, “a Muslim marriage, not a Catholic marriage.” According to House, this sentence was a clever way of saying that Riyadh could enjoy multiple spouses, as is permitted for men under Islamic law. Still, she concludes, “the United States remains Saudi Arabia’s first and paramount wife.”

Nearly a decade after House wrote those words, there is no question that Saudi Arabia pursues a multipolar foreign policy in which nations as large as China and as small as Singapore are essential to the country’s core interests. Asian investment, pilgrimages, tourism, and trade—both with the country and the region that surrounds it—are vital to realizing the goals of Vision 2030. In fact, they are so important that they have necessitated fresh approaches to even the most sensitive regional issues. A multifaceted approach also shapes how Saudis interact with Muslims in Asia, especially on issues as sensitive as Muhammad Rizieq Shihab. Even more complicated is the place of the Asian migrant workers in the kingdom, especially after the Covid-19 epidemic changed their lives along with those of millions of others across Asia who depend on their remittances.

In addressing the simmering tensions in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, Riyadh has worked with Beijing, New Delhi, and others, but it still views Washington as its chief military partner in the region. Riyadh continues to buy U.S. weapons, and its Sovereign Wealth Fund increased its U.S. portfolio from $2 billion to $10 billion in spring 2020—purchasing stakes in Boeing, Disney, Facebook, Marriott Hotels, and other companies that further the objectives of Vision 2030. For their part, U.S. diplomats continue to warn Riyadh about its growing ties to Beijing while stressing, “we’re not leaving” and we are committed to the country’s future.

These types of statements suggest that U.S. military and strategic leverage vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia is not what it was when Prince Bandar bin Sultan once likened the relationship between the two countries to a Catholic marriage. But they also point to the strength of the historic and current linkages that neither government wishes to jettison in 2020 for China or any other nation. What Abraham Lincoln once called “the mystic chords of memory” are likely to keep Riyadh and Washington aligned—even as Asia becomes a defining force in Saudi Arabia’s domestic and foreign affairs.

Sean Foley is a Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University. He is the author of The Arab Gulf States: Beyond Oil and Islam (2010) and Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom (2019) – both of which were published by Lynne Rienner Press. He has conducted extensive research in Asia and Saudi Arabia and held Fulbright grants in Syria, Turkey, and Malaysia. Follow him on twitter at @foleyse.