"We have redefined, in a short span of time, and despite uncertainty and conflict, our partnerships with Gulf and West Asia."

Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Section One

Overview

India’s relations with the Middle East are undergoing a sea change. As India has emerged as a major economic force and global player, Indian policymakers have expanded their horizons, seeing the Middle East – which they conceptualize as West Asia – in strategic terms, perhaps for the first time. Similarly, Middle Eastern countries, worried about U.S. commitment to the region and anxious to diversify their markets and economic systems, see India as an increasingly appealing partner. As a result, today India engages more countries in the Middle East on a wider range of topics and at a more substantive level than it ever has in the past.

The ties between the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East are long-standing. Cultural and commercial flows between the two regions date back to the Silk Road and maritime trade between ancient civilizations; they reached another apex when the British Raj nearly unified control over the Indian Ocean and the vast landmass of Asia above it. This cultural interchange has continued in contemporary times because India – home to the world’s third-largest Muslim population – shares natural affinities with the Middle East. Through much of India’s history as an independent nation, a commercial relationship characterized by energy trade and remittances ensured positive relations, albeit ones constrained by the stark rivalries of the Cold War, India’s ongoing rivalry with Pakistan, as well as the challenge of terrorism.

In recent years, both sides have attempted to transcend these constraints. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who won a second term in 2019, is a central figure driving this change. His push to bolster ties with the Middle East is deeply rooted in what appear to be his two overarching foreign policy objectives: (i) position India as a global player on the world stage and (ii) leverage foreign relations to boost India’s economic development and growth.

We have entered a new stage in India-Middle East relations, one that will come with its own set of challenges and uncertainties for India, the Middle East, and the rest of the international community.

The Middle East is a critical source of global energy and the western bookend to the Indian Ocean region, which India considers its sphere of influence. Therefore, it is naturally part of Modi’s foreign policy ambitions. In particular, Modi has elevated India’s relations with the Gulf countries and Israel. One of Modi’s signature schemes to boost domestic manufacturing and economic growth, the Make in India initiative, is predicated on attracting greater foreign investment. Here Modi is looking to the oil-rich Gulf economies, encouraging them to see India not just as an energy market, but also as an investment destination and economic partner. Similarly, in 2017, when he became the first Indian prime minister to visit Israel, Modi made a bet that stronger ties with Israel would aid India’s global ambitions and that Israeli technology and innovation could supercharge Indian growth.

India’s reimagining of its own role in the world and the role the Middle East can play in its economic transformation has catalyzed the shift taking place today. Engagement has blossomed across the board: in economic and energy connections, diplomatic relations, security partnerships, and people-to-people and cultural ties.

Section Two

Economic & Energy Ties

Today, policymakers in New Delhi are attempting to widen the economic lens through which their predecessors viewed the Middle East – with a focus on energy and remittances – and refocus on the Gulf countries and Israel as critical partners that can play an active role in India’s economic renaissance. That said, energy trade still remains the anchor of India–Middle East economic relations. While India’s commercial ties with the region have broadened, its ravenous appetite for energy leaves the country highly dependent on the Middle East. Around a quarter of India’s total imports are from the Middle East, with nearly 80% of these imports being crude oil and petroleum products.

India’s dependence on the Middle East has increased as the volume of its total oil imports has skyrocketed in the last two decades. Oil imported from the Middle East, which made up close to 40% of India’s total imports in 1990, has gone up in absolute and relative terms as India has become the world’s third-largest importer of crude oil. By 2005, India was getting nearly half of its oil imports from the Middle East; in 2017, it sourced nearly 64% of its oil imports from the region. During that period, India’s total imports of oil have nearly doubled! While Saudi Arabia has been its most consistent source of oil over time, India is diversifying its suppliers from the region and beyond (Russia and Mexico). In 2017, Iraq was India’s largest supplier of oil in the region, followed by Saudi Arabia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Kuwait. India is also heavily reliant on natural gas from the Middle East. Until recently, Qatar provided the vast majority of India’s long-term supplies of liquefied natural gas (LNG), but India has recently started to diversify its sources. In 2017, Qatar accounted for 52% of India’s imports of LNG, with the United States, Russia, and Australia accounting for much of the rest. However, even as Qatar’s relative share of India’s imports has declined, in absolute terms imports from Qatar have grown.

INDIA'S ENERGY MIX AND IMPORTS FROM THE MIDDLE EAST

India's Long-Term Energy Demand

Energy trade with the Middle East has been critical to India’s economic rise. According to International Energy Agency (IEA) data, in 1990, oil made up 20% of India’s total energy mix, while natural gas made up 3.5%. By 2016, when India’s overall energy needs were far greater, oil made up 25% of its energy mix and natural gas made up 5.5%. The IEA estimates that India will remain similarly dependent through 2040, with oil and natural gas making up roughly 30% of its energy mix. India is projected to have the fastest growth in energy consumption over the next two decades, meaning Middle East energy will be essential for India’s long-term economic viability. The growth in India’s energy demand between 2016 and 2040 is expected to outstrip that of China as well as a number of entire regions around the world. The economic codependency between India and the Middle East is here to stay.

Change in World Energy Demand, 2016-2040

India's Refining Boom

In anticipation of its ballooning energy needs and aware of its dependency on foreign oil, India has made proactive investments to enhance its domestic energy sector. Today, India has the second-largest refining capacity in Asia (after China) and the fourth-largest in the world. India did not develop this capacity to merely satisfy domestic demand but to become a major exporter of refined oil. India doubled its exports of refined oil between 2007 and 2017 to become the sixth-largest exporter of refined petroleum in the world, and the third-largest in Asia. It has announced plans to further expand its refining capacity by 77% by 2030. Singapore and the UAE are the largest buyers of refined petroleum from India, with India being the UAE’s top supplier of petroleum in 2017. India is also one of the top suppliers of petroleum to Israel and Saudi Arabia. India views the Middle East as a key market for its growing refinery industry and is increasingly encouraging countries in the Middle East to invest in the sector. The energy relationship between India and the Middle East is growing and becoming increasingly multifaceted.

India's Refinery Capacity & Exports

Seeking Middle East Investment

Middle Eastern countries are not a major source of foreign direct investment (FDI) for India. Modi has challenged his Gulf counterparts to change that, and the initial response has been enthusiastic. Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) have reached an agreement with India to jointly develop the largest greenfield refinery in the world in the Indian state of Maharashtra. This bold joint venture is emblematic of how India seeks to leverage Gulf investment to spur economic growth while allowing Gulf countries to diversify their energy economies. The proposed agreement, for instance, involves not just Saudi investment in an Indian refinery but also an agreement for the Gulf partners to supply at least 50% of the crude that the refinery will process.

Saudi Arabia’s investments are not limited to the energy sector. During his state visit to India in February 2019, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman declared an intention to “invest in the areas of energy, refining, petrochemicals, infrastructure, agriculture, minerals and mining, manufacturing, education and health potentially worth in excess of $100 billion.” India has secured investment pledges from the UAE as well. In 2018, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) signed a $1 billion investment agreement with India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) on energy, transportation, water, and infrastructure. In 2019, through a joint venture with NIFF, Dubai’s DP World acquired a 76% stake in the Indian railway logistics company Kribhco Infrastructure Limited, after securing a $78 million contract to build warehouses in India’s largest container port the previous year. According to The Hindu BusinessLine, “the acquisition bolsters DP World’s presence in the fast-growing inland logistics market by making it one of the top integrated rail terminal and container train operators in the country.” There is also growing interest among Gulf investors in India’s startup and technology sectors.

The investment flows are not in one direction either. India is positioning itself as a partner for the UAE in its attempts to wean the economy off its reliance on oil. Indian companies are looking to expand into the UAE’s economic zones and are involved in its energy, transportation, food processing, and information technology sectors in particular. The 2015 India-UAE Joint Statement describes India’s relationship with the UAE as multidimensional: “As India accelerates economic reforms and improves its investment and business environment, and UAE becomes an increasingly advanced and diversified economy, the two countries have the potential to build a transformative economic partnership.” Leaders in India and in the Gulf are hoping the potential translates to reality.

India’s Trade Relations with the Middle East

While energy trade has made the Middle East into a key regional trade partner for India, several attempts have been made to grow and diversify commercial ties with the region. In 2006, oil comprised more than 70% of India’s imports from the Middle East. By 2016, that number was closer to 55%. India’s exports to the region have also grown significantly. India’s major exports include chemical products, refined petroleum, precious gems and minerals, and vegetable products. The UAE is by far India’s top market in the region, absorbing more than half of India’s exports to the Middle East and nearly a tenth of its global exports, which are made up primarily of refined oil, precious gems, and metals. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), almost all of India’s exports of gold (worth $2.27 billion in 2017) end up in the UAE. Interestingly, some of this gold is initially smuggled into India from the Middle East.

Though India’s trade with the Gulf, in particular, has skyrocketed – from around 5 billion USD in 2000 to $138 billion in 2015 – it has no formal trade agreements with countries in the Middle East. Attempts to negotiate trade agreements with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Israel, and Iran over the past decade have come to naught. Moreover, some friction has surrounded energy trade as well. In recent years, Asian countries, which import more than 40% of global crude and make up an increasingly large share of the market for the Gulf’s energy, have objected to what they call an “Asian premium.” India has claimed that it pays two to three dollars more per barrel than countries in the West. In 2018, India catalyzed discussions to create a buyers forum with China, Japan, and South Korea to negotiate lower prices from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). These tensions reveal just how much is currently in transition. Asian economies like India are quickly replacing Western economies as the primary markets for Mideast energy. As they do so, they are also demanding a greater say and flexing their newfound political muscle. Given the scale of the energy trade, oil prices will continue to have a significant impact on the tenor and power dynamics of these relationships.

Exports to the Middle East

Section Three

Strategic & Diplomatic Relations

Since the turn of the century, India’s energy security and investment needs have coalesced with a newfound desire to play a more global role. As a result, India has moved deliberately to ramp up its diplomatic engagement in the Middle East. In 2003, India signed its first strategic partnership in the region with Iran. It followed suit with Oman in 2008 and Saudi Arabia in 2010. When Modi entered office in 2014, he had not said much about the Middle East and there was little indication that the region would be a high priority. According to Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, this changed after Modi’s state visit to the UAE in 2015, during which Modi and Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Mohamed bin Zayed signed a broad range of agreements. The Indian government quickly added the UAE to its short list of potential strategic partners based on an assessment that Abu Dhabi was both willing and able to substantively assist India with its economic transformation. The only other countries already on that list were the United States and Japan. Between 2014 and 2018, India invited the leaders of each (as well as France) to be chief guests at its Republic Day parade, a high symbolic honor reserved for India’s closest partners. During the 2017 state visit, when the UAE’s Crown Prince bin Zayed was chief guest, the two countries signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement.

Finally, Modi has pursued closer ties with Israel, a fellow democracy he hopes can aid India through innovation and technology. He did this by de-hyphenating Israel from Palestine in India’s foreign policy (dealing with each independent of the other) and elevating the relationship to a strategic partnership during his historic trip to Israel in 2017. Today, the relationship is durable across several areas – from robust defense sales to cooperation in areas such as agriculture, water, innovation and technology, infrastructure, pharmaceuticals, and more. Although Modi has invested significant political capital to making new regional friends like Israel, he has nonetheless maintained India’s long-term engagement with Iran. The flurry of diplomatic visits back-and-forth by Indian and Middle Eastern officials reveals just how much diplomatic effort has been expended to solidify these relations.

India-Middle East Bilateral Visits, Joint Exercises, and Naval Deployments

Under Modi, India is not only increasing the pace of diplomatic engagement with the Middle East, with a greater frequency of bilateral visits, but also sending more senior officials to the region. Modi has consistently expressed his aim to elevate ties with the Middle East, and his government has literally walked (flown) the talk. Modi’s own travel to the region proves this. During his first term, he visited the Middle Eastern nations 10 times (Iran, Israel, Jordan, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey once each; and the UAE twice). In contrast, his predecessor Manmohan Singh conducted only 4 state visits (Iran, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia) during his 10 years in office. Our analysis shows the number of Middle Eastern officials visiting India for state visits has likewise increased, as have cabinet-level trips overall. These visits have led to a long list of bilateral agreements across a broad spectrum of issues ranging from energy and investment ties, military exchanges and counterterrorism cooperation, innovation and technology partnerships, education and skill development, to tourism and cultural exchange.

Strategic Commitment

India has sought to secure these partnerships despite facing international pushback at times. Modi has been very forward-leaning toward the leaders of the UAE and Saudi Arabia in particular. When Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia faced widespread international opprobrium due to the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Modi literally embraced the embattled leader. During the prince’s state visit to India in 2019, Modi broke protocol by greeting him at the airport and enthusiastically hugging him in front of the press. India has also stuck with Iran over the past 10 years despite significant diplomatic and economic pressure from the international community and the United States to contain its nuclear program. India maneuvered to maintain oil imports from Iran and strengthen its diplomatic engagement with the country in spite of international sanctions on Iran. It secured a waiver from the Obama administration to continue energy trade with Iran. During the height of sanctions from 2012 to 2015, India was one of Iran’s most critical trade partners, with 20% to 25% of Iran’s annual oil exports heading to India (second only to China). The escalation of U.S.-Iran tensions under the administration of President Donald Trump has exerted significant additional pressure on India’s bilateral engagement with both countries. After the Trump administration reinstated sanctions against Iran, India initially obtained a waiver; however, once that waiver lapsed in May 2019, India was forced to reduce its imports of Iranian crude. The continuation of U.S.-Iran tensions is an ongoing concern for India in its policy toward the Middle East.

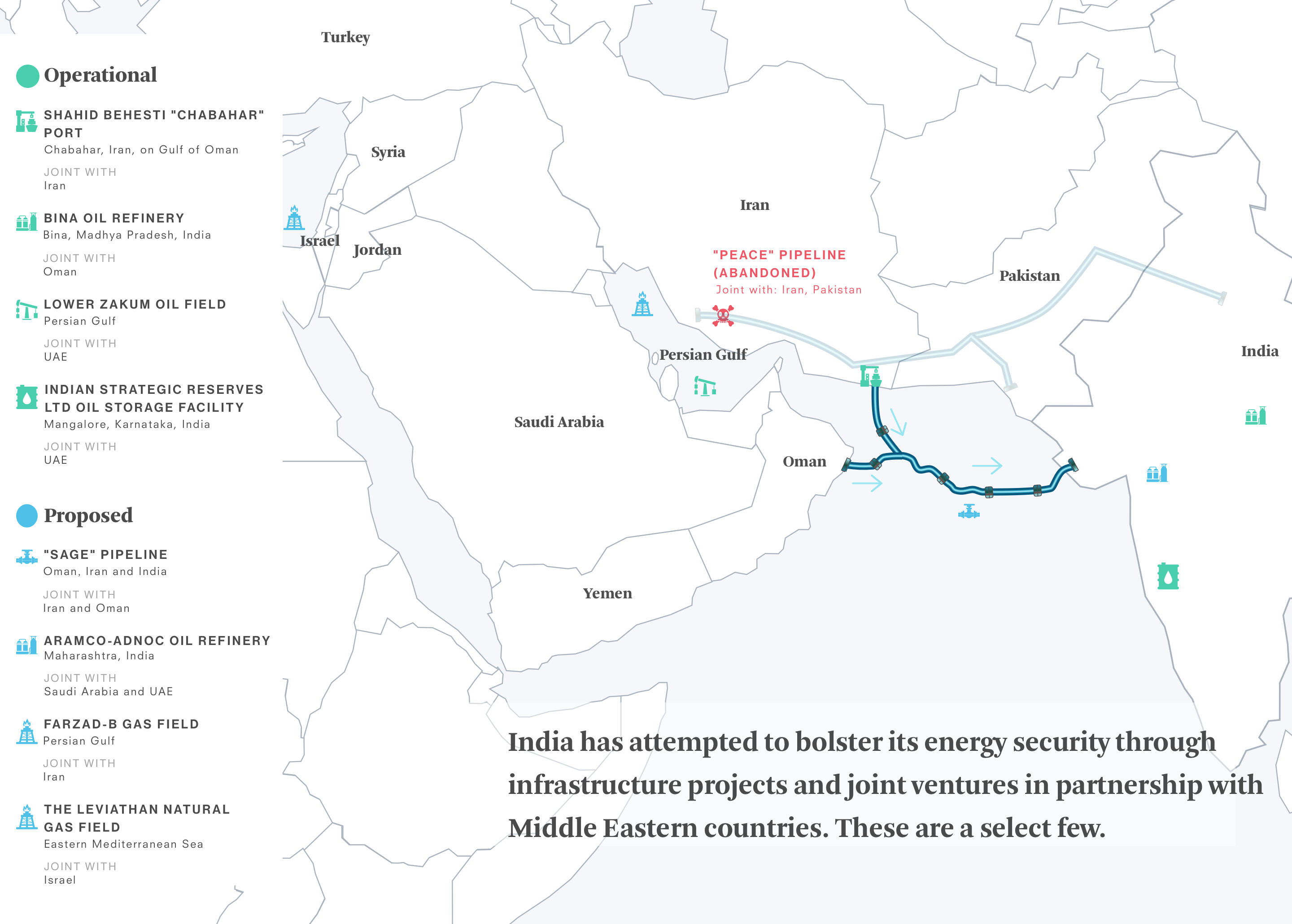

Strategic Investments and Joint Projects

India’s strategic investments and the partnerships it has forged in the region reveal its perception of the Middle East as critical to its core priorities. India has watched warily as China has increased its presence in the region and is now trying to catch up. Thus far, India’s rivalry with Pakistan has blocked it from having a direct overland trade route to the Middle East or an overland pipeline through which to securely and efficiently import energy. To rectify these challenges, India has looked to Iran, in particular, to develop a strategic foothold in the Middle East. Two of India’s most critical infrastructure projects in the region involve Iran: the Chabahar Port and the Sage pipeline. The Chabahar Port in Iran on the Gulf of Oman gives India a portal through which to ship goods overland to Central Asia, Eurasia, and the Middle East, as well as the opportunity to play a larger role in Afghanistan’s reconstruction. And the proposed Sage pipeline it hopes to develop jointly with Oman and Iran will enable India to import natural gas more cheaply and efficiently, thereby heightening its energy security.

Furthermore, India has worked to develop joint partnerships with energy companies in the Middle East to explore, refine, and store energy. The operational Bina refinery in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh (a joint venture with Oman Oil Company) and the proposed Maharashtra refinery (in which Aramco and ADNOC would have a stake) are the best examples of this. In addition, Indian companies have in multiple cases sought the right to explore Middle Eastern energy sources directly. This includes India’s ONGC Videsh obtaining a 10% stake in the UAE’s Lower Zakum Oil Field and attempting to expand Iran’s Farzad B Gas Field, both in the Persian Gulf. India is also trying to gain rights from Israel to explore a natural gas field in the Eastern Mediterranean. In addition, India has developed domestic oil storage facilities in partnership with countries such as the UAE to fortify its emergency oil reserve.

A Difficult Balancing Act

While spinning its web of relationships across the region, India has had to play a delicate balancing act to avoid getting ensnared in the region’s security challenges. Several of its partners are active rivals of one another and are entangled in complicated partnerships with other global players (namely the United States, Russia, and China). Iran is a prime example. India has strengthened its long-standing relationship with Iran even as it has become involved with Tehran’s rivals – Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the United States. In its relationship with Israel, New Delhi has to be wary that it does not overplay its hand so as to alienate Israel’s many rivals in the region as well as its own large Muslim population, both of which sympathize with Palestine. This is why, after making a historic first state visit to Israel in 2017, Modi made sure to visit to Palestine in 2018. Israel’s recent rapprochement with some Gulf countries has simplified matters, but those relations could easily fray.

Moreover, India often has to comment and vote in international fora on human rights, peace, and security issues in the region, which can be a lose-lose proposition when one is trying to please competing friends. Any votes or statements on the Israel-Palestine struggle and any commentary on the human rights records of countries in the region can quickly place India in the middle of the messy regional rivalries it hopes to avoid. India’s partners in the region also have to tread carefully when asked to choose between India and China or between India and Pakistan on particular issues. This could involve commenting on sensitive border disputes, or taking sides in a future crisis or in votes in multilateral forums like the United Nations. In such a volatile region, India’s commitment to a policy of neutrality and noninterference across the board will certainly be tested. And if India is inclined to take on a more prominent role, it may find it difficult to be a truly neutral player.

Section Four

Security & Military Cooperation

Over the past decade, the Middle East has become a critical element in India’s conceptualization of its own security interests and challenges. There are three primary drivers. First, as discussed earlier, safeguarding energy supplies and trade routes to and from the Middle East has become a priority to sustain India’s economic rise. Second, as India has raised its global ambitions, policymakers and security officials in New Delhi have come to see the Indian Ocean region as a critical sphere of influence, one where China has increasingly encroached. Finally, any instability and conflict in the region can endanger India’s large diaspora community. These factors have led India to closely monitor developments in the region, build stronger security partnerships with Middle Eastern nations, and bolster its military capabilities and maritime presence in the Indian Ocean.

Though India has generally attempted to steer clear of direct involvement in the security crises of the Middle East, it has played a role in multilateral efforts to prevent, mitigate, and resolve conflict. Indian troops engaged in peacekeeping in the region starting with the very first UN operation in 1956 – when the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) was formed in the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula after the Arab-Israeli War. Given that India is a top contributor to UN peace operations, its troops have found themselves in the region on multiple occasions. Since 1998, Indian troops have been deployed as part of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), and Indian peacekeepers have assisted the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) in the Golan Heights since 2006.

Growing Security Interests

The Indian strategic and military communities increasingly view the Indian Ocean region as a core theater. India sees maritime command over this geography as critical to its objective of safeguarding itself and its neighborhood and securing the energy and trade flows that fuel its economy. Since the turn of the century, successive Indian governments have attempted to accelerate the buildup of India’s naval power and incorporate West Asia in their strategic conceptualization of the region. In 2007, India’s Minister of Defense Shekhar Dutt stated that India’s “security environment extends from the Persian Gulf to the Straits of Malacca across the Indian Ocean,” and in 2009 India began to codify West Asia as a core element of its security strategy, in large part thanks to the Indian Navy. In its 2009 “Indian Maritime Doctrine,” the Indian Navy explicitly identified several parts of the West Asia–Indian Ocean geography as “India’s primary areas of maritime interest.” This included the Persian Gulf and its littoral; the Arabian Sea; the choke points of the Strait of Hormuz and Babel-el-Mandeb; as well as the Gulf of Oman, Gulf of Aden, Red Sea, and their littoral regions. India’s realization of the importance of the Indian Ocean region and its subsequent focus on building its naval capabilities are key reasons the Middle East has jumped up in India’s security priorities.

China’s growing influence in the region during this period redoubled India’s focus. India is increasingly sensitive to Beijing’s military activities and footprint in the region and is attempting to catch up. The Chinese Communist Party designated the Middle East a “neighbor region” at its Third Plenary session in November 2013 and identified it as a crucial part of its One Belt One Road Initiative (now the Belt and Road Initiative). Beijing has expanded its presence in the region, most crucially through the deepwater Gwadar Port in Pakistan’s Balochistan province. The port, which became operational in 2016, gives China a strategic foothold in the Arabian Sea, near the Gulf of Oman, and then the Persian Gulf. India’s development of the Chabahar Port in Iran was in a way a response to Gwadar, and India signed a naval access agreement with Oman in 2018 to use Duqm port, which is being financed heavily by China. Beijing’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean could one day give China a heightened ability to hold India’s energy supplies hostage, an unacceptable risk for New Delhi. And given the problems the China-Pakistan partnership has already created for India, policymakers in New Delhi are loath to see China establish new footholds in the Indian Ocean that would leave it surrounded by more Chinese partners.

The most acute security interest for India is the safety of its diaspora community in a region rife with conflict. Ensuring their longer-term protection and viability in the region is also essential, since the diaspora sends nearly $40 billion in remittances back to India annually. International crises have forced India to evacuate citizens from the Middle East on multiple occasions: from Kuwait in 1990, Lebanon in 2006, Libya in 2011, and Yemen in 2015. These difficult and expensive experiences crystallized how important it is for India to build stronger political and military partnerships with countries in the region so that it can quickly and smoothly extract its citizens during emergencies.

Arms Trade with Israel

Another critical component in India’s evolving ties with the Middle East has been its growing security partnership with Israel. Modi’s historic visit to Israel in 2017 and the elevation of bilateral ties to a strategic partnership marked a turning point in India’s approach to Israel. Modi’s decision to de-hyphenate the relationship with Israel and Palestine reflected the tangible benefits a stronger partnership with Israel would afford India. Chief among these and a central pillar of the relationship has been arms sales. Israel became a key arms supplier to India after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but its defense exports have reached new heights in recent years. In the past five years, India has emerged as the world’s largest importer of arms at the same time that Israel has significantly expanded its defense industry and exports. As a result, their defense trade has quickened. Between 2006 and 2011, 5% of India’s arms imports were sourced from Israel. Between 2014 and 2017, that number jumped to 15% as a result of a number of major arms deals. In 2016–2017, India signed arms deals worth more than $2.6 billion with Israeli companies to purchase naval surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems, Heron Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, and Barak-1 SAMs. There has also been cooperation to jointly develop defense technology. For instance, Israel Aerospace Industries and India’s Defence Research & Development Organization have partnered to co-develop the Barak 8 long-range SAM. Today, Indian policymakers consider Israel a key partner in their efforts to upgrade India’s defense technology.

Arms Sales From Israel

Burgeoning Defense Relationships

Given its growing security interests in the region, India has moved to craft stronger military ties and security cooperation with the Gulf countries and Israel in particular. Historically, India’s closest military partner in the region has been Oman, with which India has conducted joint military exercises for some time. In the past dozen years, India has tried to diversify its military engagement in the region. In 2008, India and the UAE began the Desert Eagle exercise between their air forces; in 2018, they conducted their first bilateral navel exercise (Gulf Star). In 2017, for the first time, the Indian Air Force engaged in a joint military exercise with Israel – the Blue Flag exercise, which included seven Western nations as well. India has signed a number of security pacts with the UAE, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, as well as a number of defense cooperation agreements with the UAE and Saudi Arabia in particular.

In 2003, India and the UAE signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on defense cooperation and established a Joint Defence Cooperation Committee to discuss shared security challenges and interests. In 2015, when Modi and Crown Prince Mohamed bin Zayed announced a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, they signed agreements to strengthen maritime security cooperation, explore manufacturing of defense equipment in India, and conduct joint military exercises. Similarly, New Delhi and Riyadh agreed to set up a Joint Committee on Defence Cooperation in 2012 to facilitate defense cooperation and followed this up with an MOU on defense cooperation in 2014. In 2016, Modi and King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud emphasized “the need to intensify bilateral defen[s]e cooperation, through exchange of visits by military personnel and experts, conduct of joint military exercises, exchange of visits of ships and aircrafts, and supply of arms and ammunition and their joint development.” They also “agreed to enhance cooperation to strengthen maritime security in the Gulf and the Indian Ocean regions.”

Pakistan and Counterterrorism Cooperation

A major element and driver of this growing security cooperation has been the increasing willingness of Gulf countries to tackle terrorism and apply pressure on Pakistan, with which they historically have strong ties. As India has eclipsed Pakistan on the economic, military, and geopolitical fronts, Gulf countries have started to rebalance their relationship toward India. Under Modi, New Delhi has also shed its older diplomatic approach, in which dealings with Middle East nations were based on their relationship with Pakistan. Today, according to C. Raja Mohan, India approaches each country in the region pragmatically, independent of Pakistan. This has created an opening for stronger diplomatic ties, and both sides have taken advantage. The UAE’s invitation to India to attend the 2019 Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Foreign Ministers meeting in Abu Dhabi was emblematic of this shift. Despite being home to one of the world’s largest Muslim populations, India had been barred from attending in the past due to Pakistan’s consistent opposition. In March, for the first time in the OIC’s fifty-year history, India participated in the forum as the UAE’s “guest of honor,” and it did so despite the OIC’s history of echoing and reinforcing Pakistan’s messaging on Kashmir. In fact, recent developments suggest that Gulf nations could adopt a more neutral position on the Kashmir issue.

Terrorism is another issue that made it difficult for Gulf countries to forge stronger security partnerships with India. India has long been critical of Gulf funding of madrassas and terrorist groups in Pakistan and has been wary of homegrown militants seeking safe haven in the Gulf. In recent years, this dynamic has started to change as Gulf countries have faced tremendous international pressure and on-the-ground blowback due to their lax approach to terrorism. When Prince Salman of Saudi Arabia visited India in February 2019, in the wake of the Pulwama terrorist attack, Saudi Arabia bluntly condemned the attack and called for “dismant[ling] terrorist infrastructures.” The message was clearly directed at Pakistan. Putting words into action, the “two sides agreed to constitute a Comprehensive Security Dialogue at the level of National Security Advisors and set up a Joint Working Group on Counter-Terrorism.” Following Pulwama, Saudi Arabia and the UAE also applied private pressure on Pakistan to work toward a peaceful end of the crisis with India. This was the culmination of several years of growing intelligence sharing and counterterrorism cooperation between India and the Gulf states. In their 2016 joint statement, the two countries “agreed to enhance cooperation in counterterrorism operations, intelligence sharing and capacity-building and to strengthen cooperation in law enforcement, anti-money laundering, drug-trafficking and other transnational crimes.”

Section Five

People-to-People Ties

The historic and commercial ties between India and the Middle East and the presence of a large Muslim population in India have created natural avenues for cultural exchange and people-to-people connections. Indian music, TV shows, and films are consumed avidly across the Middle East and offer India a level of cultural soft power that many other Asian countries lack. More than anything else, however, the flow of people drives the cultural exchange between regions, creating a number of challenges as well as benefits for India.

The presence of a substantial Indian diaspora community in the Middle East – especially Indians working in the Gulf – accounts for an astonishing number of the cultural networks between these nations. The Indian diaspora is nearly 9 million strong in the Middle East and, in some cases, makes up significant chunks of the local population. For instance, Indian expatriates in the UAE represent more than a quarter of its population. The connections made between the Indian diaspora and the local community bestow New Delhi with formidable soft power. At the same time, the presence of the diaspora offers host countries some political leverage over India and a level of assurance that India will be a consistent partner over the long term. In addition to the expatriates living in the Middle East, other types of people flows have fortified India’s ties with the region. The Hajj, for instance, is a consistent draw for Indian Muslims, who flock to Mecca and Medina in large numbers every year. In 2017, according to India’s Ministry of Minority Affairs, nearly 170,000 Indians made the pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia, and over the past decade, at least 100,000 Indians have made the pilgrimage annually. And while the number of Indian students in the Middle East is low (around 30,000), recent trends show the numbers are rising.

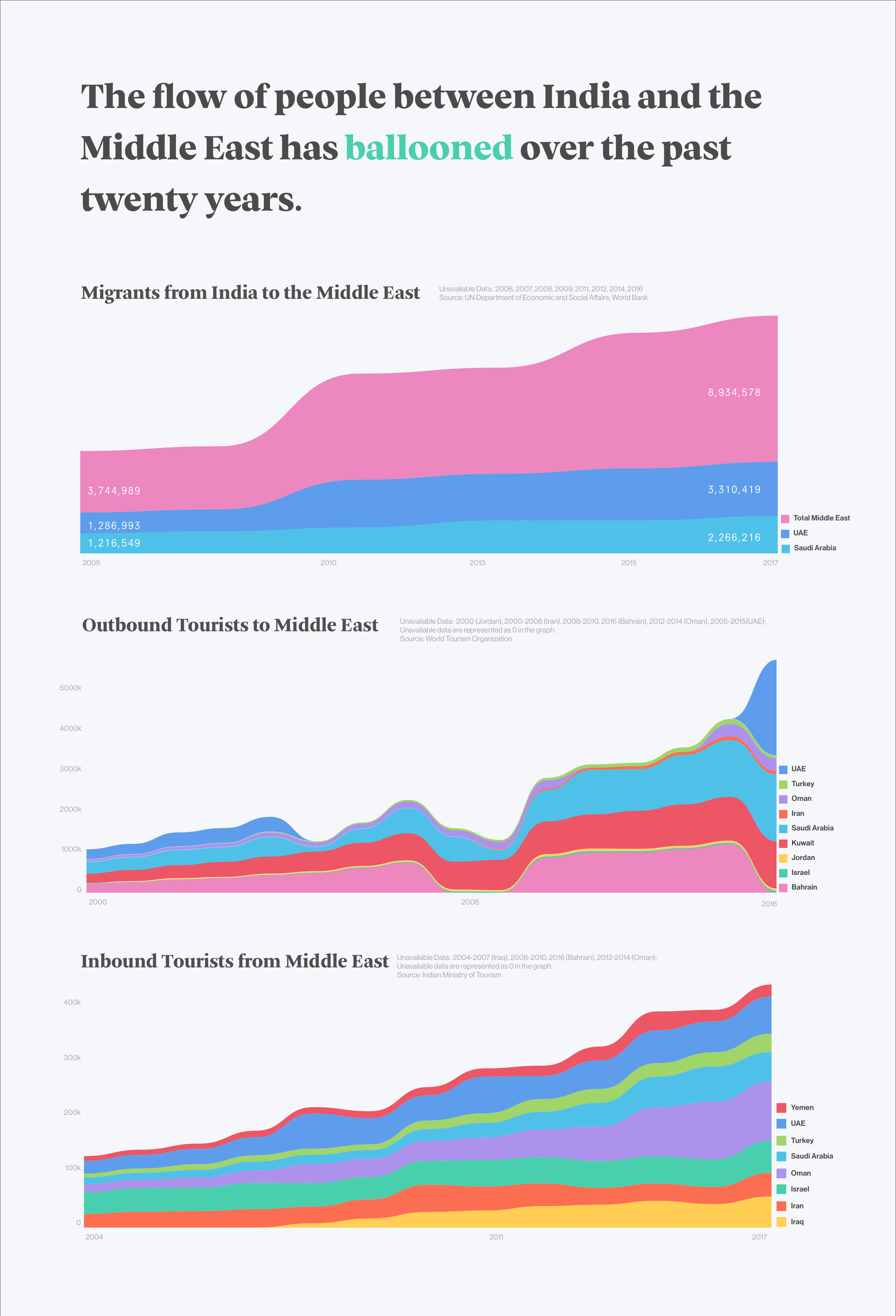

India's Diaspora and Tourism

The flow of migrants from India to the Middle East has grown tremendously since the turn of the century. In 2005, around 3.7 million Indians were in the Middle East. That number jumped to nearly 9 million in 2017, with more than 3.3 million Indians in the UAE and nearly 2.2 million Indians in Saudi Arabia, both countries where Indians make up a large number of the labor force and the biggest expatriate community. Most of the increase took place between 2005 and 2010 when the UAE was undergoing a major construction boom and welcomed a surge of immigrant labor, especially from South Asia. 41% of the current migrants in the UAE are from India. While such a large community of Indians in the UAE has been a boon to bilateral ties, it has also resulted in some complications. In 2010, unacceptable working conditions and violations of workers’ rights in the UAE generated a flurry of negative press in India. As a result, India’s Ministry of Overseas Indians signed agreements with the UAE on contracts and labor rights. In 2017, the UAE passed laws regulating work hours, vacation time, and holidays and stipulated new rules to protect foreign workers.

Tourism between India and the Middle East, while low relative to other parts of the world, has also grown tremendously in the 21st century. While consistent data is difficult to find, the number of Indian tourists to the Middle East has increased around fivefold in the past two decades: from nearly 100,000 tourists in 2000 to 500,000 in 2017. Unsurprisingly, the Gulf countries top the list of destinations for Indian tourists, with the UAE the most favored terminus in 2017, followed by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Bahrain. India is also becoming an increasingly popular tourist destination for citizens of the Middle East, with the number of tourists increasing from nearly 120,000 in 2004 to more than 400,000 in 2017. Visitors from Oman, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the UAE account for the bulk of the Middle East’s visitors to India. These rising flows of people only enhance the strong cultural and commercial ties between India and the region.

A Key Source of Remittances

Remittances are the most tangible way in which the flow of people has impacted India and shaped its policies toward the Middle East. India has been a top recipient of global remittances for several decades and has accounted for at least 10% of global remittance inflows annually for the past decade. Nearly 25 million Indians living abroad send money back home and in significant enough numbers that personal remittances have accounted for 2% to 4% of India’s GDP every year since 2000. The Indian community in the Gulf is a significant source of these funds. The Middle East is the origin of more than half of India’s total remittance inflows, and Saudi Arabia and the UAE alone account for 36%. In 2017, India received $38 billion in remittances from the Middle East. As Kadira Pethiyagoda has written, these funds are critical for poverty alleviation and serve as a vital source of foreign exchange for India. The long-term viability of Indian expat communities in the Middle East is, therefore, an important priority for Indian policymakers.

Remittances from the Middle East

Section Six

Conclusion

India’s relations with countries in the Middle East have blossomed over the past decade but the future trajectories of these ties are not without uncertainty. We have entered a new stage in India–Middle East relations, one that comes with its own set of challenges for India, the Middle East, and the international community.

Indian officials have predicated the push for stronger ties with the region on the idea that this will buttress India’s economic transformation and bolster its strategic interests. There will be challenges on both fronts. Modi has devoted immense political capital in improving ties with the Gulf and Israel in order to attract investment and high-level technology. Thus far, the investment relationship has largely been about promises and potential. A true test of whether India’s burgeoning romances with the Gulf will blossom into true partnerships will be whether these lofty investments ever materialize.

Even greater uncertainty exists on the security front, given the volatility of the Middle East. Any new conflict that threatens India’s energy supplies or inflates energy prices could take a toll on India’s economy and complicate ties. Moreover, any instability or active conflict between regional players will test India’s commitment to a policy of neutrality and noninterference. With the United States – the primary regional security provider of recent times – expressing growing doubts about its regional footprint, and China increasing its influence, India may be forced to take on a greater role than it is willing or ready to. Already, in the wake of attacks on tankers in the Persian Gulf, the U.S. military is asking nations to help safeguard shipping lanes. Will India, which is a primary beneficiary of the energy resources passing through the waterway, decide to be party to such efforts? If the United States really does diminish its role, can India afford not to contribute?

The current escalation in U.S.-Iran tensions highlights many of the challenges India is likely to increasingly face in the Middle East. The U.S. maximum pressure campaign on Iran has created difficulties for India in its bilateral engagement with both countries and for its Middle East strategy as a whole. It is caught between a great power and close strategic partner on the one hand and a regional partner that provides India with substantial energy supplies and its primary strategic foothold in the region (through Chabahar Port) on the other. Thus far, India has been critical of the U.S. position but has agreed to cut its oil imports, while seeking to preserve its relationship with Iran to some degree. But even this level of compromise may prove more difficult in the future in the face of mounting pressure not just from the United States, but also from Israel and India’s Gulf partners. This is unlikely to be the last or even the most difficult choice India faces in the Middle East. How it chooses to respond will shape its future and that of the region more than it has ever before.