UAE

The United Arab Emirates’ Pivot to Asia

Jonathan Fulton

September 21st, 2020

"The UAE has utilised the experience of other advanced countries, like Singapore, South Korea and China in confronting the [COVID-19] virus."

Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan

Section One

Overview

The idea of an “Asian Century” has gained considerable traction in recent years. The global economic center of gravity, located around the mid-north Atlantic Ocean in 1980, is projected to be squarely between India and China by 2050. Asia accounted for approximately a third of global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2000 and by 2040 should account for more than 50%. This structural change in the global economy is causing reverberations across Eurasia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a textbook example of this shift.

With a long history of cooperation with the United States and the United Kingdom, the UAE has traditionally been oriented westward, especially in its political and security considerations. In the twenty-first century, a more balanced approach is taking shape, as Asian countries and markets are beginning to feature more significantly in the UAE’s political, economic, strategic, and cultural interests.

Extra-regional powers have always played an important role in the UAE’s foreign and security policies due to its unique characteristics. For one, it is a relatively small state in a dangerous region. It has a population of just under 10 million and of that approximately 88% are expatriate. Because of this unusual demographic composition, the UAE’s economy is heavily reliant on a workforce without a path to citizenship, creating a sense that many could pack up and leave in bad times. A threatening security environment compounds this economic dilemma. The UAE’s armed forces have an estimated 50,000 troops. Meanwhile, its neighbor and rival Iran is a country of just under 82 million, with a nearly 400,000-strong military force. The UAE lacks the conventional means to respond to such asymmetry and as a result has made the long-standing Defense Cooperation Agreement with the United States a major pillar of Emirati security. However, in recent years inconsistent signaling out of Washington has contributed to a sense that a more diversified set of extra-regional partners would better serve the UAE’s interests. That is not to say that the United States is on its way out; as Hoyakem and Roberts describe in a recent report, relations with India and China, among others, “are expected to complement and supplement, not replace, the U.S. security cover.”

The UAE has been successful in using its economic power to address its security dilemma. It is a global energy power and a major source of foreign direct investment and has established itself as the most business-friendly country in the Middle East–North Africa (MENA) region. This means that rich and powerful countries and companies from around the world are invested in a safe and stable UAE. Not long ago, many of these were from the West, but increasingly we see economic relations intensifying between the UAE and a wide range of Asian powers. Its ambitious diplomatic efforts, evident in the dramatic recent announcement that the UAE was normalizing relations with Israel, has contributed to a perception among extra-regional powers that have to navigate a challenging Middle East that the UAE is a useful partner.

During his 2019 state visit to China, Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince and the UAE’s de facto ruler Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed said that the two countries were “laying pillars of a road map for the next 100 years.” As this essay shows, the foundations for the UAE’s outreach to Asia are already deep and indicate that the crown prince’s statement is not merely the empty rhetoric of a state visit, but rather evidence of changing dynamics in Asian–Middle East relations.

Section Two

Economic & Energy Ties

THE CENTRALITY OF ENERGY TRADE

As a major oil exporter, much analysis on the UAE naturally begins with energy. It has the world’s seventh-largest proved oil reserves at just under 98 billion barrels and is also the world’s seventh-largest producer, at approximately 3 million barrels per day (bpd). Hydrocarbon exports are worth approximately 20% of the UAE’s export revenue, accounting for 30% of its GDP.

Given the importance of energy exports to its economy, the UAE’s energy trading partners play a major role in its economy, and Asian countries feature significantly. Over the past 10 years, the UAE’s top 10 export destinations have consistently included India, Japan, China, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand. Data from Chatham House’s Resource Trade show that fossil fuel exports from the UAE to five Asian countries in 2018 – China, India, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea – were worth nearly $58 billion. Since the federal budget for that year was announced as AED51.4 billion ($13.9 billion), the significance of the Asian energy trade is apparent. It has to be emphasized that this is not a blip on the radar; Asia will continue to be a major market for Gulf hydrocarbons. The growth of the Asian middle class will drive up demand for consumer goods, and oil- and gas-derived petrochemicals such as fertilizers, lubricants, and food preservatives will be a big part of that – Asian hydrocarbon demand is not decreasing. Despite real efforts to diversify energy use, oil consumption is projected to grow in all major Asian economies in the coming decades. China and India will drive much of this growth, with Chinese oil consumption projected to increase from 13.1 million bpd in 2014 to 20.8 million bpd in 2040. India’s oil demand is forecast to hit 10 million bpd by 2040, up from 4.7 million bpd in 2017. Southeast Asia’s demand is expected to increase from 4.7 million bpd India’sto 6.6 million bpd. Both Japan and South Korea, with export-driven economies and very little in the way of domestic energy resources, rely heavily on Gulf energy as well; the UAE supplies Japan with around 25% of its oil and South Korea with 8%. The UAE will therefore continue to focus on Asian markets, and ADNOC, Abu Dhabi’s energy giant, has announced that it plans to increase its crude production capacity to 3.5 million bpd to support future demand in Asian markets.

UAE's Energy Exports To Asia

Diversifying the Energy Relationship

A sign of Asia’s growing importance in the UAE’s energy sector was seen in the most recent awarding of stakes for a 40-year offshore concession. The previous legacy concession was dominated by Western oil companies, upon which the UAE relied for technology and expertise. This recent round reflected a shift, as ADNOC was motivated by “the need to secure outlets in the world’s key demand growth center, Asia.” This round of contracts started in 2015, and Asian oil companies were well represented. Japan’s Inpex was awarded a 5% stake and South Korea’s GS Energy a 3% one, both in 2016. The next year, China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) signed for an 8% stake and CEFC for a 4% one. In 2018, a consortium of three Indian oil companies – ONGC Videsh, Indian Oil Corporation, and Barat PetroResources – also signed concessions with ADNOC. These three together represent more than 2.65 million bpd of refining capacity; with India the world’s third-largest oil consumer, this deal provides ADNOC with a foothold in a major long-term market.

At the same time, energy prices have been in decline since 2014, a trend that this year’s Covid-19 pandemic will only further exacerbate. ADNOC has already started to adjust to this new market reality by increasing its emphasis on downstream production. With the expectation that the market share of petrochemicals will grow 150% by 2040, ADNOC CEO Sultan al Jaber has said that the company is repositioning itself as a “leading global downstream player.” To achieve this, it is coordinating efforts with Asian partners. For example, ADNOC and Saudi Aramco are jointly building a 1.2 million bpd refining complex in India at an estimated investment of $70 billion, with the two companies together taking a 50% stake. This is reflective of a larger trend, as ADNOC has been especially active in Asian downstream investments in recent years. In 2019 alone, it signed cooperation agreements with China’s Rongsheng Petrochemical Co. and China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC), another with Wanhua worth potentially $12 billion, and one with Indonesia’s PT Petramina for $3 billion worth of investments into Indonesia’s energy infrastructure. Mubadala, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, is in talks about a $6 billion refinery in Pakistan’s Baluchistan region.

The UAE has also been signing several contracts with Asian firms to develop its own domestic energy capacity and to support major projects, such as its $45 billion “downstream silicon oasis” project in Ruwais, which is projected to transform a small town 230 km outside Abu Dhabi into a refining, petrochemical, and conversion hub. In March 2018, South Korea’s Samsung Engineering signed two contracts worth $3.5 billion with ADNOC on a major upgrading project on the Ruwais refinery. Other major projects are underway in the emirate of Fujairah, located on the Arabian Sea and featuring the world’s second-largest bunkering port. In February 2019, South Korea’s SK Engineering & Construction signed a contract with ADNOC to build an underground crude storage facility in Fujairah, a deal that al Jaber linked to enhancing the UAE’s energy security. ADNOC also signed a $600 million pipeline investment project with Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC, which controls 6% of the assets. In one of China’s first significant infrastructure projects in the UAE, a CNPC subsidiary built a pipeline connecting the Habshan oilfield to the Fujairah port. It became operational in 2012 and has a capacity of 1.8 million bpd. In 2013, Sinopec and Singapore’s Concord Energy invested $252 million in a Fujairah oil-storage facility, the largest in the region, and Sinopec leases half.

The UAE has been working to reduce its own dependence on oil with the goal of 56% of power generation from clean energy by 2050: 38% from gas, 12% from clean coal, and 6% nuclear. This has created opportunities to expand energy relationships beyond hydrocarbons. Most noteworthy, in 2009 South Korea’s Korea Electric Power Corporation and the UAE’s Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation signed a $20.4 billion contract to design, build, and operate four ARR1400 nuclear power units at the Barakah nuclear power plant, which opened in 2020. It is expected to generate a quarter of the UAE’s electricity, offsetting 21 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year. The UAE has also engaged with China in this regard. In a major deal, China’s Silk Road Fund partnered with Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power on the fourth phase of Dubai’s Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, the world’s largest solar plant at 44 km2, providing clean energy for 320,000 residences and reducing 1.6 million tons of carbon emissions per year. This was a sign of things to come, as in May 2020 Silk Road Fund purchased a 49% stake in ACWA, whose CEO said the collaboration will support “ambitious growth planned in the renewables sector in MENA, Africa, Asia, and Central Asia.”

Taken together, we see a set of energy relations transitioning away from the typical oil import-export dynamic toward a more sustainable and well-rounded one that creates deeper levels of interdependence and represents an important role for Asian countries in the UAE’s energy future.

COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC COOPERATION

The UAE’s economic relations with Asia are, like their energy relations, becoming deep and multi-faceted. The UAE has leveraged its strength as a regional transport and logistics hub and Dubai’s unparalleled regional financial infrastructure to make the Emirates an economic base of operations for many international firms. As a result, many Asian companies and financial institutions have established a strong presence.

All Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states acknowledge the acute need to develop more diverse and sustainable economies. The single resource rentier model is unsustainable, a point Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash recently made when looking at a post–Covid-19 UAE. Noting that Gulf countries would need to take this moment to reconsider their economic model, he said, “We have been for many years trying to escape that model with varying degrees of success but I think this is going to accelerate the necessity for us to find something a little bit more sustainable.” Compared with its GCC neighbors and partners, the UAE has developed a relatively sound foundation for a post-oil economy. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayd said, “in 50 years when we might have the last barrel of oil, the question is: when it is shipped abroad will we be sad? If we are investing today in the right sectors, I can tell you we will celebrate at that moment.” Leaders across the Gulf are motivated to achieve this goal; whether they succeed will depend largely on the international economic partnerships they are able to develop.

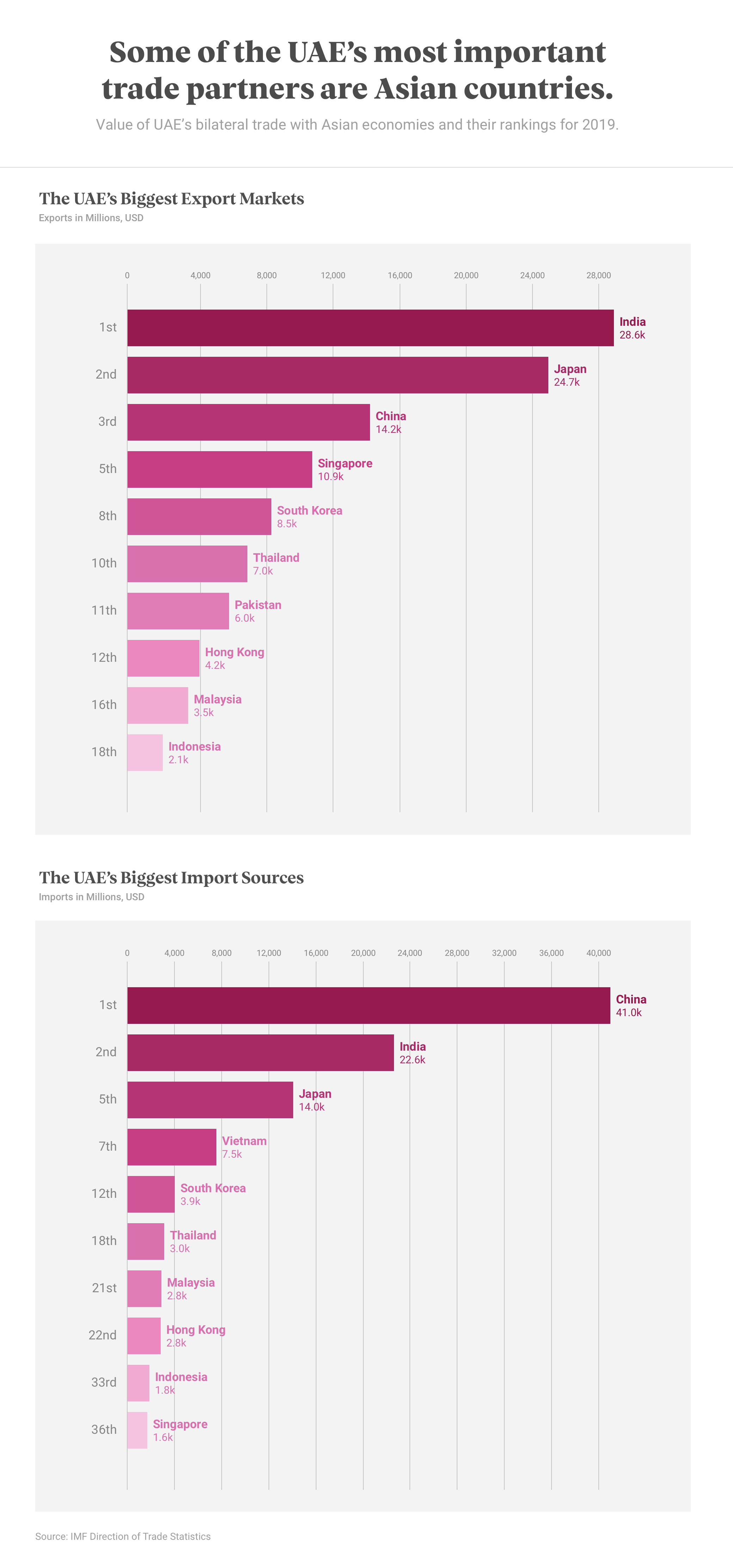

Growing UAE-Asia Trade Ties

The UAE has certainly established a strong foundation for this through its trade with Asia. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2019 the UAE was the top overall Middle Eastern trading partner for India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, as well as the top Middle Eastern export destination for China, Japan, and Vietnam. Furthering its trade ties, the UAE has made use of free trade agreements (FTAs) across Asia, signing bilateral FTAs with Pakistan (2006), India (2012), Kazakhstan (2012), the Maldives (2014), and South Korea (2015). It has an FTA with Singapore through its GCC membership and is in talks with China and Japan, as well as multilateral FTAs with South Korea, India, and Pakistan.

Another mechanism the UAE has relied on is trade and investment forums with Asian countries, provinces, or cities. For example, the past three years have seen the Vietnam-UAE Trade and Investment Forum, the Abu Dhabi Investment Forum in Seoul, the China-UAE Industrial Capacity Cooperation Demonstration Zone Investment Promotion Conference, the UAE-Japan Investment Forum, Dubai Week in Shanghai, and the India-UAE High Level Task Force on Investment (2019). The UAE and Singapore have institutionalized the Abu Dhabi–Singapore Joint Forum, held annually and rotating between the two cities.

Within the UAE, Dubai is a major hub for Asian trade, anchored by the Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority (JAFZA), which has been designated “Best Seaport in the Middle East” every year since 1996. JAFZA was established as a free zone in 1985, allowing for 100% foreign ownership and offering visa-streamed processing for foreign employees, subsidized energy, and a transportation infrastructure unmatched in the region. Given the UAE’s relative stability and business-friendly environment – it ranked 16th globally and first in the Middle East in the World Bank’s Doing Business Report in 2020. JAFZA has become a regional base of operations for more than 7,500 international companies, including more than 800 from India, 244 from China, and 145 from Japan. Masami Ando, the managing director for Japan External Trade Organization in Dubai, explained, “the country’s strategic location, good infrastructure, stable government and hospitable business culture make the UAE a very inviting place to do business.” A Chinese banker in Dubai emphasized that “the culture there makes it easier. Chinese companies use Dubai as a gateway to the MENA region. In more traditional countries like Saudi Arabia, there are fewer Chinese companies, as they find it more difficult to manage the cultural differences.” The emphasis on culture here speaks to an important point. The UAE’s business-first model means that it has established a comfortable environment for white-collar expatriates, with excellent health care, international schools, comfortable housing, and religious and personal freedom. For companies operating in MENA, the UAE provides a welcoming atmosphere.

UAE-Asia Investment Flows

UAE-Asia economic relations are also lubricated through investment, both inward and outward, as well as through joint investment platforms. The UAE is the top destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Arab world and ranked 27th globally. In 2018, it drew in $10.4 billion, accounting for 36% of FDI flows into Arab countries, and by region Asian countries were the largest source of FDI into the Emirates, followed by Europe, North America, and Africa. To maintain its position as an attractive FDI destination, the UAE announced in July 2019 a list of 122 economic activities across 13 sectors where foreign investors would be allowed 100% ownership, including renewable energy, space, agriculture, manufacturing, transport, logistics, and hospitality. China has been especially active in investments and contracting in the UAE, with an estimated $34.7 billion invested since 2005, with energy and real estate taking the lion’s share. India likewise is a major investor into the UAE, especially Dubai. More modest but not unsubstantial, Japanese investment into the UAE has reached more than $3.9 billion, and Singapore has stock investments in the Emirates valued at $3 billion.

FDI also moves from the Emirates to Asia. The UAE was ranked the 19th largest source of global FDI in 2018, with outflows totaling $15 billion. The UAE has stock investments in Singapore valued at $3.6 billion and is the tenth-largest investor in India, with stocks valued at $4.76 billion, making it the top source of investments among Arab countries. The importance of Emirati investments into India is evident in the range of infrastructure projects planned, including railways, ports, airports, industrial corridors, and roads. This is being institutionalized through partnerships between India’s National Investment & Infrastructure Fund and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and DP World.

The UAE has established joint investment funds as another means to develop economic relations with Asian states. During Mohammed bin Zayed’s state visit to China in 2015, Mubadala, one of the UAE’s sovereign wealth funds, signed a $10 billion joint investment fund with China Development Bank Capital and China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange, called the UAE-China Joint Investment Fund, capitalized equally by both governments. President Xi Jinping described the fund as a means of strengthening strategic and economic relations, while the crown prince said it “represents the next stage of our partnership as we seek to work more closely in developing our economies and contributing to global growth.” DP World has established a joint investment fund with India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund, set up in 2018 and capitalized with $3 billion, to “acquire assets and develop projects in sea and river ports, freight corridors, special economic zones, inland container terminals, and logistics infrastructure such as cold storage.” Korea too has an investment cooperation agreement with the UAE; the Investment Corporation of Dubai and Korea Investment Corporation signed a deal in 2015 “that facilitates communication between the two organizations while empowering them to jointly explore investment opportunities in the UAE, South Korea, and other countries.”

Migrant Labor & Remittances

One interesting element of the UAE-Asia relationship is the large role of Asian labor in the Emirates’ economy. The relatively small local population has resulted in reliance on expatriate labor, and much of this has come from Asia. Nearly 60% of the country’s population comes from South Asia alone, and there are substantial Chinese, Filipino, and Indonesian communities as well – these three countries together represent more than 1 million, or around 10 percent, of the UAE’s population. As such, remittances from the UAE play a large role in the economic relations between the UAE and many Asian countries. The UAE was the world’s second-largest outward remittance country in 2018 after the United States; in 2019, remittances from the Emirates were valued at AED 165 billion, or approximately $44 billion. Of this, the top three destinations for this outflow were India, Pakistan, and the Philippines.

In short, through trade, investment, and energy, the UAE has established itself as a major Middle East partner throughout Asia, a process that has become apparent with the depth and breadth of engagement over the past decade.

UAE's Top Remittance Destinations

Section Three

Strategic & Diplomatic Relations

These dense economic ties are not taking place in isolation. The UAE has been actively developing its political and diplomatic relations across Asia in recent years, befitting such a large growth in shared economic interests. This has involved frequent high-level bilateral visits both to and from the UAE as Emirati leaders and their Asian counterparts have worked to strengthen relations that until recently were relatively underdeveloped.

The UAE’s increased clout in Middle Eastern political, economic, and security affairs has made Abu Dhabi an important stop for global leaders, and recent years have seen a growth in Asian state and official visits. Given the centrality of Middle East energy to Asian economies, strong relations with influential regional states are important, and we have seen a corresponding outreach from Asian capital cities to Abu Dhabi. Five Korean presidents have visited since the Barakah deal was announced in 2009. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has visited four times, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has paid three state visits. With much of the Middle East marred by political, economic, and security turbulence, the UAE’s relative stability and increasingly muscular regional foreign policy make it an important partner for leaders with an interest in the region.

This is especially relevant in light of the normalization of diplomatic relations between the UAE and Israel, announced in August 2020. While this was perceived as a dramatic turn of events in the Middle East, the two countries have been cooperating quietly for many years. To openly establish ties was a matter of formalizing a bilateral relationship that had become increasingly mature. For Asian countries with interests in the Middle East, the UAE-Israel relationship is significant in that it makes it easier to navigate regional tensions, allowing them to continue strengthening their own ties to Israel without alienating their partners in Abu Dhabi.

UAE-Asia Bilateral Visits and Joint Exercises

A New Tool in UAE’s Diplomatic Toolkit

In recent years, a new tool has been added to the diplomatic kit: strategic partnership agreements. The UAE signed a strategic partnership agreement with China in 2012 during then-Premier Wen Jiabao’s state visit, and this was upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership – China’s highest level of diplomatic cooperation – when President Xi visited in 2018. Other major Asian powers have also signed partnerships with the UAE: India (2017), Japan (2018), South Korea (2018), and Singapore (2019).

The UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not articulated a strategic partnership policy or set conditions or determinants for designating a state a strategic partner. However, it seems to be the case that a country has to boast a combination of economic and political power and demonstrate high levels of trustworthiness through long-running and sustained diplomatic engagement. The joint communiqués announcing each partnership are consistent in the expectations set out, expressing an intention to cooperate across several areas of shared interests. Among the many issue areas typically emphasized are political, economic, security and defense, cultural, educational, environmental, energy, aviation, food security, medical, consular, and human resources development. They also usually establish a mechanism to routinize coordination through regularly scheduled meetings. For example, the agreement with Singapore is directed by their respective Ministries of Foreign Affairs, with day-to-day management run through their embassies. The Singapore-UAE Joint Committee has convened twice, in 2014 and 2017, both times co-chaired by cabinet ministers: Singaporean Foreign Minister Balakrishnan and the UAE’s Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed (2014) and Minister Gargash (2017). In 2018, the UAE appointed Khaldoon Al Mubarak, CEO of Mubadala, as the country’s first Special Presidential Envoy to China to help coordinate the strategic partnership, while China has designated a similarly high-profile Special Representative in Yang Jiechi, a member of the Politburo Central Committee and director of the Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission.

UAE’s Elite Diplomacy toward Asia

This combination of frequent state visits and appointing high-level envoys addresses a particular challenge the UAE faces. With a relatively small local population – approximately 12% of the country is Emirati – the country has to stretch its human resources substantially. The UAE has diplomatic relations with every Asian country except North Korea (its diplomatic mission there was terminated in 2017), but it has two shortcomings in building its diplomatic capacity in Asia: a relatively small team of foreign service officers and a low base of homegrown knowledge production about Asia, including language and area expertise. The establishment of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs–affiliated Emirates Diplomatic Academy (EDA) in 2014 is an attempt to address this. It is the training center for would-be Emirati diplomats, with a one-year program that takes in approximately 60 students a year and provides professional training. Of these, the majority take jobs with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs upon completion of the program. Part of the training includes language study, with classes offered in Russian, French, German, Spanish, Farsi, and Chinese. It also features a research center consisting of four clusters, including Gulf-Asia relations, initiated by Minister Gargash to begin filling the local knowledge gap. During a recent discussion, some EDA students told me that while they are focusing their studies on China and Southeast Asia, the majority of their classmates are studying Europe and the United States, which are considered more prestigious postings. The Asia-oriented students, on the other hand, felt that they would gain a competitive advantage over their colleagues, believing that the UAE’s Asian missions will ultimately offer more professional opportunities in the future.

This would seem to explain, at least partially, why UAE-Asia diplomacy takes place at the elite level. Foreign policy issues are largely the purview of an inner circle. The Minister of Foreign Affairs Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed is the stepbrother of President Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed and full brother of the crown prince. His role is complemented by that of Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash, who has held this position since 2008. In addition to the work of these two, Crown Prince Mohamed bin Zayed and Prime Minister Mohammad bin Rashid Al Maktoum play key roles in the UAE’s diplomacy and are frequent visitors to Asian capital cities. It was evident early in their careers that these two would be major actors in the UAE’s foreign policy, as both began cultivating international relationships before assuming executive roles in government. Mohamed bin Zayed represented the UAE at Emperor Hirohito’s funeral in 1989, and both he and Momammad bin Rashid accompanied founding president Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan on his trip to China in 1990. Both have been frequent visitors to Asia, with Mohamed bin Zayed traveling to China four times since then, most recently in 2019; South Korea three times; and India and Japan twice. In 2019 alone, he traveled to Pakistan; Singapore, where he signed the comprehensive strategic partnership; South Korea; China; Indonesia; and Malaysia, where he attended the coronation of his longtime friend and Sandhurst classmate King Sultan Abdullah Ahamd Shah. Prime Minister Sheikh Mohammad bin Rahsid led a delegation to Beijing for the Belt and Road Forum in April 2019, signing $3.4 billion worth of deals for Chinese investments into Dubai while there.

A final important aspect of the UAE’s Asian engagement is its growing interest in the Indian Ocean region. In 2019, it assumed a two-year position as chair of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), an international organization with 22 member states and nine dialogue partners with an emphasis on regional cooperation and sustainable development. As chair, the UAE’s focus will be maritime security, facilitation of trade and investment, cultural and tourist exchange, and women’s economic empowerment.

The UAE released a promotional video celebrating Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the Emirates in 2019. During the visit, Modi was conferred with the Order of Zayed, joining China’s President Xi Jinping (2018) as the only other current Asian leader to receive the UAE’s highest civilian decoration.

Section Four

Security & Military Cooperation

The security realm is the most underdeveloped aspect of the UAE’s relations with Asian states. This can be attributed to two structural factors: the UAE’s preoccupation with its own regional security concerns and its long-standing security relationship with the United States. These result in two subsidiary factors: the UAE’s limited capacity to project power beyond the Middle East and a reluctance of Asian states to needlessly get involved in what appears to be an intractable security environment.

The Gulf is best understood as a regional security complex. Gulf states and their leaders are more concerned with one another than with issues beyond their immediate region. As a result, foreign and security policy decisions are first and foremost filtered through the lens of how they would affect an intensely competitive regional dynamic. For Emirati leaders, key concerns at this level include material threats from Iran or its proxies, ideological threats represented primarily by the Muslim Brotherhood and political Islamic groups, or instability spreading through fragile or failed states throughout the Middle East. As such, the bulk of the UAE’s security resources are devoted to Middle East issues rather than less immediate ones farther afield.

Losing the U.S. Security Umbrella?

The UAE’s deep security partnership with the United States is another consideration. After the Carter Doctrine was announced in 1980, U.S. regional presence intensified. The Defense Cooperation Agreements (DCA) the United States signed with the UAE and three of its GCC partners (Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain) in the early 1990s solidified the U.S. commitment to maintaining a regional status quo that favored the GCC states and isolated Iran. This resulted in a massive U.S. military presence in the Gulf region in support of this status quo, with approximately 4,000 troops stationed in the UAE, a significant air force presence at the Al Dhafra Air Base, and training of Emirati troops.

The security umbrella provided by the United States means GCC states – and their extra-regional trading partners – have not had to take on the responsibility of maintaining open shipping lanes. For the UAE, this means that its military resources remain devoted to regional issues. In the period since the first wave of Arab uprisings, the UAE has transitioned from its traditionally modest foreign policy in the region to a more muscular one. Its relatively small armed forces of approximately 50,000 personnel have participated with the United States in operations in Somalia, the Balkans, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria, and with Saudi Arabia in Yemen. This increase in Emirati military engagement led former U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis to refer to the UAE as “Little Sparta” and describe its troops as “great warriors,” while Anthony Zinni, former commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, claimed, “It’s the strongest relationship that the United States has in the Arab world today.”

The U.S. presence in the Gulf has also shaped Asian approaches to regional security. Knowing that their trade and investment opportunities are guaranteed by the American security commitments, other states have taken advantage and deepened their engagement in the region without the associated costs. While China has often been derided as a free rider, it is not unique in this – most states doing business in the Gulf have been doing it on the back of the U.S. military.

The perception of a softening U.S. commitment to Gulf security in recent years has been changing this calculus, however. This is a long-standing concern of Gulf leaders and is a structural feature of an asymmetrical partnership that is based on interests rather than values. U.S. interests in the Middle East have been changing since the disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003, with both American political parties and much of the public expressing a desire for a reduced role in the region. Under President Donald Trump, this process has continued, despite initial hopes among Gulf leaders that his election signaled an expansion of American power in the Gulf. A Tweet from President Trump in 2019 is indicative: “China gets 91% of its Oil from the Straight [sic], Japan 62%, & many other countries likewise. So why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many years) for zero compensation. All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been a dangerous journey. We don’t even need to be there in that the U.S. has just become (by far) the largest producer of Energy anywhere in the world!” This is not just rhetoric; the Trump administration’s responses to several recent events have confounded many throughout the region and reinforced the long-running perception of a U.S. retreat. During the second half of 2019, oil tankers were attacked, presumably by Iranian agents, in the UAE’s Fujairah port, and then again in the Sea of Oman. The U.S. president called for a drone strike against Iran in retaliation but called it off at the last minute. These attacks were followed in September 2019 by a major strike on Saudi Aramco’s facilities in Abqaiq and Khurais, which the president described as “an attack on Saudi Arabia, and that wasn’t an attack on us.” For some leaders in the Gulf, the U.S. commitment to deterring Iranian aggression appears less than ironclad, making outreach to other extra-regional countries an important response to an unstable regional security environment.

Growing Security Cooperation with Asian Partners

While the U.S. military preponderance in the Middle East remains unchallenged and its DCA with the UAE was renewed in 2017 for another 15 years, Emirati leadership has been steadily building up its security cooperation with Asian states partly through the new strategic partnership mechanism. Security cooperation is featured in its Asian strategic partnerships but with very little explicit detail. Despite this vague articulation, the UAE has security interests that converge with those of each of these states.

Security has come to feature in the UAE–South Korea relationship since signing the Barakah nuclear deal in 2009. Since Korea is still officially at war with North Korea and with a challenging East Asian security environment, there is little public support in Korea for a substantial military role in the Middle East, making a deeper level of security engagement with the UAE politically difficult. Korea has had a defense attaché posted to the embassy in Abu Dhabi since 2006; however, prior to the Iran nuclear deal, North Korean missile technology transfers to Iran were the only significant issue on the UAE’s Korean Peninsula agenda. Even so, as part of its goal to engage with a broader range of security partners, the UAE linked the Barakah deal to defense cooperation. According to former Defense Minister Kim Tae-Young, the deal includes “a clause that guarantees the Korean military’s automatic intervention in an emergency in the UAE.” While controversial in Korea when this came to the public’s attention, Minister Kim described it as a “low-risk” commitment because “the UAE is a country in which a war had not taken place for a long time.” The most prominent aspect of their security cooperation is the UAE Military Training Cooperation Group Akh Unit (Akh Unit), a deployment of elite special forces troops in the UAE that trains Emirati special forces and conducts joint training exercises and counterterrorism training. The Akh Unit has been deployed in the UAE since 2011.

Japan also includes security cooperation in its partnership agreement, although it too faces domestic political and constitutional constraints preventing a larger security commitment. Article 9 of the Japanese constitution states, “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.” Since the constitution took effect in 1947, this has prevented Japan from pursuing a more militarized foreign policy, limiting its ability to project power in the Gulf. The UAE has expressed a desire for defense cooperation with Japan, however, and Tokyo has been finding ways to work around its constitutional limitations. During Prime Minister Abe’s 2014 visit to the UAE, security was on the agenda, and the next year they held their first bilateral security dialogue. In 2017, Japan appointed a defense attaché, Commander Hiromasa Takahashi, to the UAE for the first time, a move that then-Ambassador H. E. Kanji Fujiki described as a part of efforts to advance security cooperation discussed during Abe’s 2014 visit.

Prime Minister Abe visited the UAE again in early 2020 and security was a key feature of the agenda. He made it explicit, saying, “the UAE plays a key and pivotal role in pursuing sustainable development, peace and stability in the Middle East.” The June 2019 attack on the Kokuka Courageous, a Japanese tanker in the Gulf of Oman, reiterated the need for secure shipping lanes and was likely a major motivating factor for the trip. During the visit, the prime minister announced that Japan would deploy a Maritime Self-Defense Force (SDF) destroyer with 270 seamen to the Gulf in early 2020, a mission the prime minister described as necessary because “Thousands of Japanese ships ply those waters every year including vessels carrying nine tenths of our oil. It is Japan’s lifeline.” This response from Japan may be in acknowledgment of U.S. expectations that its allies shoulder a larger part of the security burden; more likely, it is a message to Gulf leaders that Japan is willing to contribute to regional security issues. Not technically a naval force, the SDF can be deployed for investigation and research missions, a point Assistant Foreign Minister Ohtaka Masao was careful to emphasize, claiming the deployment would be “for information gathering, for the self-defense Japanese role in the region in the future.” During the visit, Mohamed bin Zayed offered support and cooperation for the mission, although it was not clear what shape that would take given the UAE’s relatively limited naval capabilities.

During his visit to the UAE in March 2018, South Korean President Moon Jae-in made a rare visit to see Korean special forces of the Akh Unit, which has been deployed to the UAE since 2011. (Arirang News)

Strategic Hedging

The UAE has also been developing nascent security and defense cooperation with China, although this presents bigger challenges. While Japan and South Korea are both U.S. allies, China is more and more its strategic competitor. The UAE therefore has to maintain a delicate balance to strengthen ties with Beijing without alienating Washington. At the same time, Chinese leaders are conscious of the fact that the U.S. security role in the Gulf has provided significant benefits for China as well, so disrupting this is not in its interests either. To that end, security cooperation between the UAE and China has thus far been at a low level. The UAE purchases armed drones from China, but this too is influenced by the United States; American drones are acknowledged as better than Chinese ones but require approval from the U.S. Congress to be sold overseas. Therefore, the Emirati purchases from China are filling a gap in the market that the UAE would prefer be addressed by the United States. The Trump administration, recognizing the market it is missing out on, has been considering ending the system for congressional review of foreign weapons sales, but this would be politically difficult to pass through Congress, facing opposition from both sides of the aisle.

In its security and defense outreach to Asia, the UAE’s approach should be seen as strategic hedging. The United States is “their indispensable and most capable ally” and remains the security partner of choice in Abu Dhabi. At the same time, an over-reliance on a partner that is increasingly signaling a desire to minimize its commitments is a dangerous liability for a relatively small state in a volatile environment. As such, the UAE is diversifying its relationships with Asian partners, although these are expected to be supplements to that with the United States, rather than a replacement. No Asian country offers the same range of security commitments as the United States, and none has the same kind of capacity to support the UAE in its regional security concerns. At the same time, the depth of Asian nations’ interests in the Emirates offers other forms of leverage that can contribute to security. For example, China’s large expatriate population and significant assets and businesses in the UAE suggest that Beijing would not respond favorably should Iran threaten those interests. Given the one-sided nature of the China-Iran relationship, it appears that Beijing has significant influence in Tehran. As such, the UAE-China partnership contributes, albeit indirectly, to Emirati security. The current trajectory indicates that Asian states will continue to haltingly increase their security role with the UAE, and Abu Dhabi is keen to engage.

Section Five

People-to-People Ties

Given the UAE’s long orientation toward the West, it is starting from a rather shallow point as far as relations with Asia at the non-elite level are concerned. India and Pakistan are exceptions, as long-standing historical ties make for a deep level of cultural ease. With Southeast and East Asia, people-to-people and cultural relations are at a nascent stage, but there is recognition that this is an important facet to develop.

Religion & Migrants Form Foundation for Cultural Ties

The UAE’s demographic imbalance creates opportunities for cultural outreach. The UAE’s population of approximately 10 million is overwhelmingly expatriate, estimated at nearly 88%. The last census was taken in 2010, but the results were not released, making accurate data difficult to confirm. However, embassies have estimated statistics, and other governmental sources provide reasonably accurate representations of the demographic composition of the UAE.

Anyone who has visited the country would not be surprised to learn that the majority of the population – nearly 60% – is from South Asia. This is based on long historical connections between societies along the Arab side of the Gulf and in India and Pakistan, which largely explain the strong cultural foundation that has facilitated the UAE’s economic and political relations with those countries. The Indian population of the UAE is estimated at more than 3.4 million, Pakistan’s at 1.2 million, Bangladesh’s at 710,000, and Sri Lanka’s at 303,000. Taken together, it is not surprising that Emiratis have a deep level of awareness of and comfort with South Asian societies and culture. On the other hand, East Asian populations in the UAE are smaller and came to the region more recently, which has resulted in a relative deficit in people-to-people relations. Therefore, the UAE has had to construct the means of bridging a cultural divide with East Asian countries, whereas this has happened organically over generations with South Asian nations.

Religion is an obvious means of outreach for the UAE in Asia, and its more moderate approach to Islam is appealing to Muslim states and societies. Many Asian states have significant Muslim populations, and the UAE has used religious donations and networks to improve relations. “Mosque diplomacy” is a common feature of the UAE’s outreach, with one private group based out of Ras al-Khaimah, Al Rahmah Charity Association, having built 4,350 mosques around the world since the foundation was established in 1988. It has also built religious, cultural, social, and educational centers. The UAE has funded the construction of numerous mosques and Islamic learning centers in Malaysia, China, Indonesia, India, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, among Asian countries.

Religious outreach extends beyond Islam. With such a large expatriate population, the UAE has a diverse religious landscape; it is 76% Muslim, 9% Christian, 10% Hindu or Buddhist, with other religions making up the remaining 5%. In 2016, the prime minister announced the creation of the Ministry of Tolerance with a mission to “eradicate ideological, cultural and religious bigotry in the society.” The government declared 2019 “the year of tolerance” and sponsored several tolerance-themed events throughout the year. That year it announced that Abu Dhabi would open the UAE’s first Hindu temple in 2020 (a room over a Dubai market shop was allowed to be designated a temple in 1958 by Rashid Al Maktoum, father of the present ruler of Dubai). Also in 2019, the UAE hosted Pope Francis for a three-day visit, the first time a pope has traveled to the Arabian Peninsula. This was especially important among the Filipino community of nearly 750,000, as well as the large Catholic Indian population of the Emirates.

UAE's Demographic Breakdown by Nationality

Building Educational and Cultural Bridges

Since the UAE lacks the history of strong people-to-people connections with East Asia that it has with South Asia, it has been using educational outreach as a means of advancing those ties. The UAE established the Sheikh Zayed Center for Arabic Language and Islamic Studies at China’s Beijing Foreign Studies University in 1994 and then completely refurbished it in 2012 with a $2.8 million donation. The center offers bachelors, masters, and doctorates in Arabic language. This has clearly paid useful soft-power dividends for the UAE; in 2012, eight out of the twelve Chinese ambassadors serving in Arab states were graduates from the center.

The growth in educational ties goes both ways. The UAE has been greatly expanding its knowledge of Asian language, culture, and society, a necessary development if the country is going to cultivate a homegrown base of knowledge production and expertise. The Confucius Institute operates two centers in the UAE, one at the University of Dubai and another at Zayed University (ZU). ZU offers free, non-credit Chinese-language classes and typically draws 200 students per year. Abu Dhabi also hosts the Korean Cultural Center, one of only two in the Middle East (the other is in Cairo), and it offers 25 Korean-language courses and averages 350 students per year. A UAE-Japan Cultural Center also opened in Abu Dhabi in 2008 and offers Japanese-language instruction.

Perhaps the most significant development for educational ties came during Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed’s state visit to Beijing in 2019, when it was announced that the UAE was expanding Chinese-language instruction into its public school K-12 curriculum. This began in 2017 with a pilot program of 10 schools with 20 native-speaking Chinese teachers and doubled the following year. By 2019, there were 60 schools participating in the program with approximately 200 teachers. The Ministry of Education rolled out the program with a report that noted a growing interest for Emiratis “to understand the Chinese language and culture” and attributed this to the “historic peak” in the bilateral relationship. That the pilot program has been extended to all schools in the UAE is evidence that the government realizes that a deeper level of cultural understanding of China is crucial.

Cultural outreach has also expanded. While the UAE does not have a dedicated cultural center in South Korea, it has taken advantage of the Korea-Arab Society to boost its image in the country. The year 2020 is the 40th anniversary of Korea-UAE relations; part of the celebration is an ongoing UAE-Korea Cultural Dialogue that will sponsor events in Korea such as an Emirati film perspective during an Arab Film Festival. The Korean Cultural Center holds several cultural programs, exhibitions, and performances, including Korean movie screenings, Korean cooking classes, and of course K-Pop events; like much of the rest of the world, the UAE is addicted to K-Pop.

The UAE has also worked to develop cultural ties to China. In 2017, China was the guest of honor at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, sending a delegation of more than 100 publishers and literary stars such as Yu Hua and Cao Wenxuan. This was part of a larger project to enhance the UAE’s awareness of Chinese literature, which also featured a program sponsored by the Crown Prince’s Court to have Chinese classics translated into Arabic through Beijing Foreign Studies University.

The UAE’s Ministry of Culture and Knowledge Development along with the Culture Directorate of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs held UAE-China Week to coincide with President Xi’s 2018 visit and after the success of the event announced it would be held annually. Hala China, jointly sponsored by Meraas and Dubai Holding, is a Dubai-based initiative to “enhance economic and cultural exchange and drive investment cooperation between Dubai and China.” It hosts a range of events, such as film festivals, recitals, and fashion shows. Its premier event is centered on Chinese New Year. In 2020, it was expected to be the largest Chinese New Year festivity outside of China, featuring performances, festivals, and parades for 50,000 spectators.

Section Six

Conclusion

Taken together, the different facets of the UAE’s outreach to Asia described here give evidence of a substantial foundation for a sustainable long-term set of relationships. Economically centered by design, different elements have been steadily increasing in importance, and the structure of the UAE’s Asian Century is starting to take shape.

The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic offers a dramatic example of this. When the coronavirus first broke out in China, the UAE was a ready donor, providing material and rhetorical support. It was included in a list of 21 countries that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson publicly thanked for providing “friendly understanding, support, and help.” Its symbolic gestures of projecting the Chinese flag on several landmark buildings in Abu Dhabi and Dubai was appreciated by the Chinese embassy, with its charge d’affaires saying in an interview, “When Burj Khalifa, Adnoc Headquarters, and other UAE iconic landmarks lit up the colors of the Chinese national flag and slogans of solidarity with China on February 2, many Chinese living and working here in the UAE were moved to tears.”

Beyond the political messaging, however, China and the UAE have been steadily cooperating on their Covid-19 response. In March 2020, the UAE’s G42, an artificial intelligence firm, signed a partnership with China’s BGI, a genetics company, to build a massive Covid-19 detection lab. It has been used to aggressively test for the virus, giving the UAE one of the world’s highest per capita test rates. Since then, China National Biotec Group has been authorized by the UAE’s Ministry of Health and Prevention to begin phase three trials of a vaccine in the UAE.

This close cooperation between an important U.S. ally and its major strategic competitor is a concern for Washington, with one U.S. official warning that the UAE risks “rupturing the long-term strategic relationship they have with the U.S.” There is no sign that the UAE is willing to scale back this cooperation, however. The U.S. response to Covid-19 does not inspire confidence in its partners or allies; in a public health crisis, leaders will work with partners that have demonstrated some level of success. The UAE's Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah reinforced this point, describing China as “a role model for disseminating hope for successfully fighting COVID-19” while praising “the decisive counter-coronavirus arrangements taken by the Chinese leadership and the Chinese people's compliance with these measures to bring the pandemic under control inside Chinese territories over the past period.”

China is not the UAE’s only Asian partner that it can turn to in this crisis. Cooperation in public health is a feature in its strategic partnership agreements with both South Korea and Singapore; while these countries’ experiences with the coronavirus have been challenging, they can draw on best practices from governments that have been at the forefront in dealing with it.

At the same time, the coronavirus crisis has also highlighted some of the underlying problems in UAE-Asia relations, especially with regard to its massive South Asian expatriate population. The case of India alone is illustrative, with 500,000 Indian residents of the UAE having registered to be repatriated, and more than 130,000 having returned home by early July. Approximately 36,000 Pakistanis have lost their jobs in the UAE since the pandemic began. In a country where residency visas are linked to employment, the dramatic economic slowdown threatens the Emirates with a labor drain. While other Gulf countries, notably Kuwait, have portrayed the expat flight as a means of addressing underemployment for citizens, the UAE recognizes that it is heavily reliant upon foreign workers, and that “an exodus of expatriates” could “prolong the virus-induced slowdown.” This may lead to a reconsideration of the country’s labor and residency policy as the coronavirus has laid bare the economic vulnerabilities inherent in its economic model.

When the UAE begins to transition from the immediate crisis of the pandemic to a long-term post-coronavirus world, it is going to require a deep pool of partners across diplomatic, economic, and security issues. The gains it has made across Asia will continue to expand and require coordination across a wider set of issues, resulting in deeper and more multi-faceted relationships.

Jonathan Fulton is an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. His books include China’s Relations with the Gulf Monarchies, Regions in the Belt and Road Initiative, and External Powers and the Gulf Monarchies.