South Korea

South Korea’s Evolving Ties with the Middle East

Hae Won Jeong

July 28th, 2020

"[Our] commitment to the Middle East remains steadfast. Since taking office, President Moon Jae-in has worked arduously to redouble Korea’s diplomatic, economic and cultural engagements in this region."

Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha

Section One

Overview

Emerging out of the ravages of the Korean War and Japanese colonial rule, the expansion of South Korea’s diplomatic, commercial, and strategic ties with the Middle East was facilitated by the rapid industrialization pursued during the Park Chung-hee era from 1961 to 1979. South Korea established diplomatic relations with most Middle Eastern countries during the Cold War, but it was not until the start of the twenty-first century that its bilateral cooperation with the Middle East took off. Its partnerships in the region were mainly concentrated in the energy and construction sectors in the 1970s and 1980s. Over time, Middle Eastern countries became invaluable to South Korea due to its dependency on oil as a key engine of its economic development.

At the turn of the century, South Korea–Middle East relations became more interdependent due to South Korea’s increased state capacity coupled with the Middle Eastern countries’ drive for economic diversification and post-conflict reconstruction efforts in the region. Today, with globalization in retreat in the West and the global balance of power shifting rapidly, geopolitical currents have reinforced bilateral and interregional engagements between Asia and the Middle East. For instance, the legacies of both U.S. President Barack Obama’s Pivot to Asia and President Donald Trump’s America First doctrines have led countries in the Middle East to look for new partners, while rising powers in Asia have recognized the need to broaden their international engagement. The groundwork for deepening commercial and strategic ties with the Middle East was laid in recent years during the Roh Moo-hyun (2003–2008) and Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013) administrations. As a consequence, the scope of South Korea–Middle East partnerships has deepened on the economic front and expanded to strategic, diplomatic, and people-to-people ties since the early-to-mid 2000s.

Today, South Korea has diplomatic relations with 18 countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The frequency of high-level visits between South Korea and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Iran, and North African countries in recent years has enhanced South Korea’s relations with the region. South Korea’s ties with the Middle East also received a boost from its innovative and bureaucratic capacity and competitive human resources. Additionally, South Korea has sufficient material resources as a high-income donor country and is ranked as the world’s sixth-largest potential military power in the Global Firepower rankings. As a result, South Korea has been able to cement its status as a middle power despite geopolitical challenges and thus is no longer considered a “shrimp among whales” in East Asia.

Yet, South Korea’s foreign policy in the Middle East is at a crossroads today. Both endogenous and exogenous factors are at play. Internally, since the Moon Jae-in administration took office in May 2017, it has faced key policy choices that will impact Korea’s foreign policy. On the one hand, President Moon Jae-in’s nuclear phase-out policy has stirred controversy and complicated burgeoning nuclear energy cooperation with the region. On the other hand, South Korea’s excellent COVID-19 crisis management has enhanced its public diplomacy and soft power projection. Externally, geopolitical volatility in the Middle East, U.S. sanctions on Iran, and political and economic transitions in the post–Arab Spring countries all pose challenges for policymakers in Seoul.

Section Two

Economic & Energy Ties

South Korea’s bilateral cooperation with Middle Eastern countries is multifaceted but continues to be primarily driven by energy security and economic interests. Strong commercial ties with Middle Eastern economies have also facilitated extending cooperation to emerging, innovation-oriented sectors—namely information and communications technology (ICT), renewable energy, healthcare, and food and water security. Commercial interests overseen by South Korea’s family-run conglomerates (chaebols) have been at the crux of international cooperation with the Middle East. As a resource-deficient economy, South Korea imports nearly all of its energy to support these national industries; crude oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports from the Middle East account for 73.5% and 40% of imports, respectively. South Korea, alongside Japan and India, is one of the top three importers of LNG from Qatar, which is the largest exporter of LNG in the world.

South Korea's Energy Mix and Imports From The Middle East

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), in 2017, petroleum accounted for the highest percentage of South Korea’s energy consumption (44%), which was followed by coal (29%), natural gas (14%), nuclear energy (11%), and other renewable energy (2%). Despite the energy deficit, South Korea has the world’s sixth-largest refinery industry and is home to SK energy, GS Caltex, and S-Oil, three of the top five companies with refining capacity in the world. Apart from domestic refineries, South Korea also has acquired stakes in overseas oil concessions, such as its GS Energy’s 10% stake in the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) Al Dhafra petroleum and a 3% stake in Abu Dhabi National Oil Company’s (ADNOC) onshore concession.

At the same time, South Korea’s overall energy consumption declined in 2019 for the first time in 10 years due to the drop in exports and the slowdown in industrial outputs. While the proportion of South Korea’s natural gas, coal, and nuclear energy consumption has been on the rise relative to oil consumption since the mid-1990s, the level of oil consumption has fluctuated over time as oil demand and consumption levels hinge on oil prices, economic growth, and export markets. South Korea remains highly dependent on the Middle East for oil, as the latter has supplied as much as 82% of its crude oil demands recently.

South Korea has the third-largest oil-refining capacity in the Asia-Pacific region and the sixth-largest oil refining capacity in the world. Multiple conglomerates operate the nation’s global downstream operations, such as SK Energy (the nation’s top oil company), GS-Caltex, S-Oil, and Hyundai Oilbank.

Notably, 2019 marked robust cooperation between South Korea and Saudi Aramco in the downstream industry. In a move to accelerate the $2 billon merger between Hyundai’s shipbuilding unit and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Company, Hyundai Heavy Industries Holdings sold 17% of its stake to Saudi Aramco in April 2019, in a $1.25 billionn deal. As Saudi Aramco became the second-largest shareholder of Hyundai Oilbank, the deal created a synergy effect in expanding Saudi crude oil supply to Asia while increasing Saudi Aramco’s global footprint in the downstream industry. Building on its earlier investments in S-Oil in 1991, two months later, Saudi Aramco also signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with S-Oil for launching a $5.8 billion Steam Cracker and Olefins downstream project in June 2019. Around the same time, Saudi Aramco and the Saudi Arabian Industrial Investments Company (Dussur) inked 12 agreements worth multi-billion dollars with South Korean companies – Hyundai Heavy Industries, Hyundai Oilbank, Hyosung Group, GS Holdings, and Korea National Oil Corporation (KNOC) to collaborate on shipbuilding, engine manufacturing, refining, petrochemical projects, and the expansion of a hydrogen ecosystem.

South Korean companies have also been actively involved in oil and gas refinery projects in Iran. In 2017, SK E&C signed a $1.88 billion Iran oil refinery contract and a $3.6 billion agreement to build and operate five new gas-powered plants; in 2016, Hyundai E&C won the tender to build a $500 million 500-MW power plant in Zanjan.

Nuclear Energy Cooperation with Jordan and the UAE

South Korea’s energy cooperation with the Middle East, traditionally confined to fossil fuels, has expanded to renewable energy in the past decade. South Korea is increasingly helping some Middle East countries diversify their energy mix. South Korea officially expressed an interest in becoming a nuclear energy technology exporter when its Ministry of Knowledge Economy (renamed Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy in 2013) announced a plan to export 80 nuclear power reactors by 2030. South Korea first exported its nuclear technology to Jordan and the UAE in December 2009. The Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI) and Daewoo E&C were the principal contractors awarded the concession to build Jordan’s first research nuclear reactor for Jordan Research and Training Reactor (JRTR); in the same month, the consortium led by the state-owned Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) won the $20 billion contract to build the UAE’s 5,600-MW Barakah nuclear power plant.

The construction of the $160 million 5-MWt Jordanian nuclear research reactor, which began in 2010, was completed by December 7, 2016. The total amount of South Korea’s investment in JRTR is $82.8 million. As Jordan’s first nuclear research reactor, the JRTR was aimed at promoting R&D, producing radioactive isotopes for medical research, and training nuclear engineers.

The UAE’s Barakah nuclear power plant represents the first time South Korea exported the APR-1400 nuclear reactor. Three thousand South Korean workers from Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) contributed to the construction of the plant, and the Korean Eximbank provided $2.5 billion as a direct loan. The first nuclear reactor was completed in May 2017; in March 2020, it became the first nuclear power plant in the Arab world. The Barakah nuclear power plant is projected to supply up to a quarter of the UAE’s electricity demands and help curb 21 million tonnes of carbon emissions per year.[5] The successful launch of Barakah’s reactor unit was equally groundbreaking for South Korea’s nuclear industry, showcasing its competitiveness for other international nuclear energy tenders.

While the negotiations for a second nuclear power plant project in the Arab world is currently underway with Saudi Arabia, the Moon administration’s proposed nuclear phase-out policy has hampered South Korea’s efforts to promote the export of its nuclear technology. Whereas the two former center-left presidents, Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun, had adopted a more pragmatic stance on nuclear energy, it remains to be seen whether South Korea will be able to minimize potential disruptions to future nuclear energy projects. Conversely, a nuclear phase-out policy would potentially result in an increase in South Korea’s dependence on fossil fuel imports.

South Korea’s Burgeoning Engineering, Procurement, and Construction Industry

South Korea’s strong construction sector has served as a secondary vehicle for strengthening bilateral partnerships with the Middle East. South Korean engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contractors have capitalized on cost-effectiveness, flexibility, and timely deliverance of projects to gain an edge in the international market. Three of the top 10 EPC companies in the world are South Korean: Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Engineering, and SK E&C. In recent years, South Korea has clinched deals for major infrastructure, oil and gas, and power plant construction projects across the GCC countries, Iran, and Iraq.

By 2012, the GCC countries accounted for 60% of South Korea’s overseas EPC contracts; since 2002, the MENA region has had the highest value of South Korea’s EPC contracts. The Korean Eximbank also played a pivotal role in financing mega projects in the Middle East, including the Barakah nuclear power plant and JRTR. Samsung C&T built the iconic Burj Khalifa skyscraper in a joint consortium with Bexis (Belgium) and Arabtec (UAE). Apart from this, Hyundai E&C also procured a $3.6 billion contract for the construction of the 13-km Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah Causeway in Kuwait—the world’s fourth-longest bridge that connects the Shuwaikh Port with Doha, Qatar–that opened in May 2019. In Bahrain, a Samsung Engineering–led consortium built an award-winning sewage treatment plant for the Hidd, Muharraq governorate in 2014. In Saudi Arabia, South Korea’s KHNP inked an agreement with King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy (KA-CARE) in March 2015 to construct two 330-MWt pressured water System-integrated Modular Advanced Reactor (SMART) units for seawater desalination and electricity generation.

The growth in many of these newly emerging partnerships is contingent on the global economy. Earlier this year, South Korean firms SK Energy and S-Oil slashed their refinery output capacities by 90% and 80%, respectively, in conjunction with the OPEC+ deal and COVID-19. Similarly, the EPC sector has lately been facing headwinds due to the triple whammy of the U.S.-China trade war, low oil prices, and COVID-19. With the exception of Kuwait, which granted entry ban waivers to 106 employees in 25 South Korean construction companies in April, the uncertainties surrounding the global economic slowdown resulting from the recent pandemic have hampered South Korean companies from clinching new business deals and resuming construction projects. The outlook in the short-to-medium term is rather grim, but trends from the past decade also suggest that the economic downturn is likely to rebound.

The growth in many of these newly emerging partnerships is contingent on the global economy. Earlier this year, South Korean firms SK Energy and S-Oil slashed their refinery output capacities by 90% and 80%, respectively, in conjunction with the OPEC+ deal and COVID-19. Similarly, the EPC sector has lately been facing headwinds due to the triple whammy of the U.S.-China trade war, low oil prices, and COVID-19. With the exception of Kuwait, which granted entry ban waivers to 106 employees in 25 South Korean construction companies in April, the uncertainties surrounding the global economic slowdown resulting from the recent pandemic have hampered South Korean companies from clinching new business deals and resuming construction projects. The outlook in the short-to-medium term is rather grim, but trends from the past decade also suggest that the economic downturn is likely to rebound.

Value of South Korea’s Engineering, Procurement and Construction Contracts by Region (2002-2020)

Section Three

Strategic & Diplomatic Relations

In recent years, South Korea made great strides in enhancing its diplomatic ties with the Middle East. In particular, there were frequent high-level visits and robust economic cooperation with the UAE and Saudi Arabia. South Korea’s diplomatic relations with the Middle East continue to be driven by geo-economic interests. Based on these interests, South Korea has prioritized strengthening diplomatic ties with the region’s major oil-producing countries.

However, South Korea’s commercial ties with Iran and Iraq have been hamstrung by geopolitical factors and U.S. policy. For instance, South Korea’s push for hydrocarbon and EPC deals with these countries has been fraught with bureaucratic barriers and political tensions. The challenges with regard to Iraq mainly stem from Baghdad’s weak bureaucratic capacity and political frictions between the latter and the northern Kurdistan regional government. Seoul’s relations with Tehran have been severely complicated by U.S. sanctions on Iran, crippling the Iranian economy and stifling South Korea’s ability to engage with Iran commercially.

South Korea Bilateral Visits

South Korea’s Special Strategic Partnership with the UAE

In the past two decades, South Korea’s bilateral partnership with the UAE has deepened. Former South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun was the first South Korean president to visit and sign a security cooperation agreement with the UAE in 2006 and 2007. While South Korea is the fourth-largest exporting partner of the UAE, the Korea-UAE relationship is notable because it includes cooperation in a broader range of fields relative to South Korea’s other regional partners. In March 2018, Moon made the UAE his first official Middle Eastern destination after taking office. During that visit, South Korea’s diplomatic relations with the UAE were elevated to special strategic partnership. Both parties agreed to expand cooperation in renewable energy, medical tourism, and healthcare and to increase aviation routes between the two countries. The breadth of agencies involved in bilateral cooperation today is a symbol of the many shared interests between the two countries. The UAE Ministry of Economy, the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO), and the South Korean Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and Startups have signed MOUs for partnerships in intellectual property and patents management systems and innovation. Abu Dhabi’s Department of Economic Development and South Korea’s Ministry of Science and ICT have signed an agreement to cooperate in science and technology, while Abu Dhabi’s Department of Energy and the South Korean Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy are pursuing cooperation in renewable energy. South Korea has also agreed to participate in Dubai Expo 2020, which has been rescheduled to open in October 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

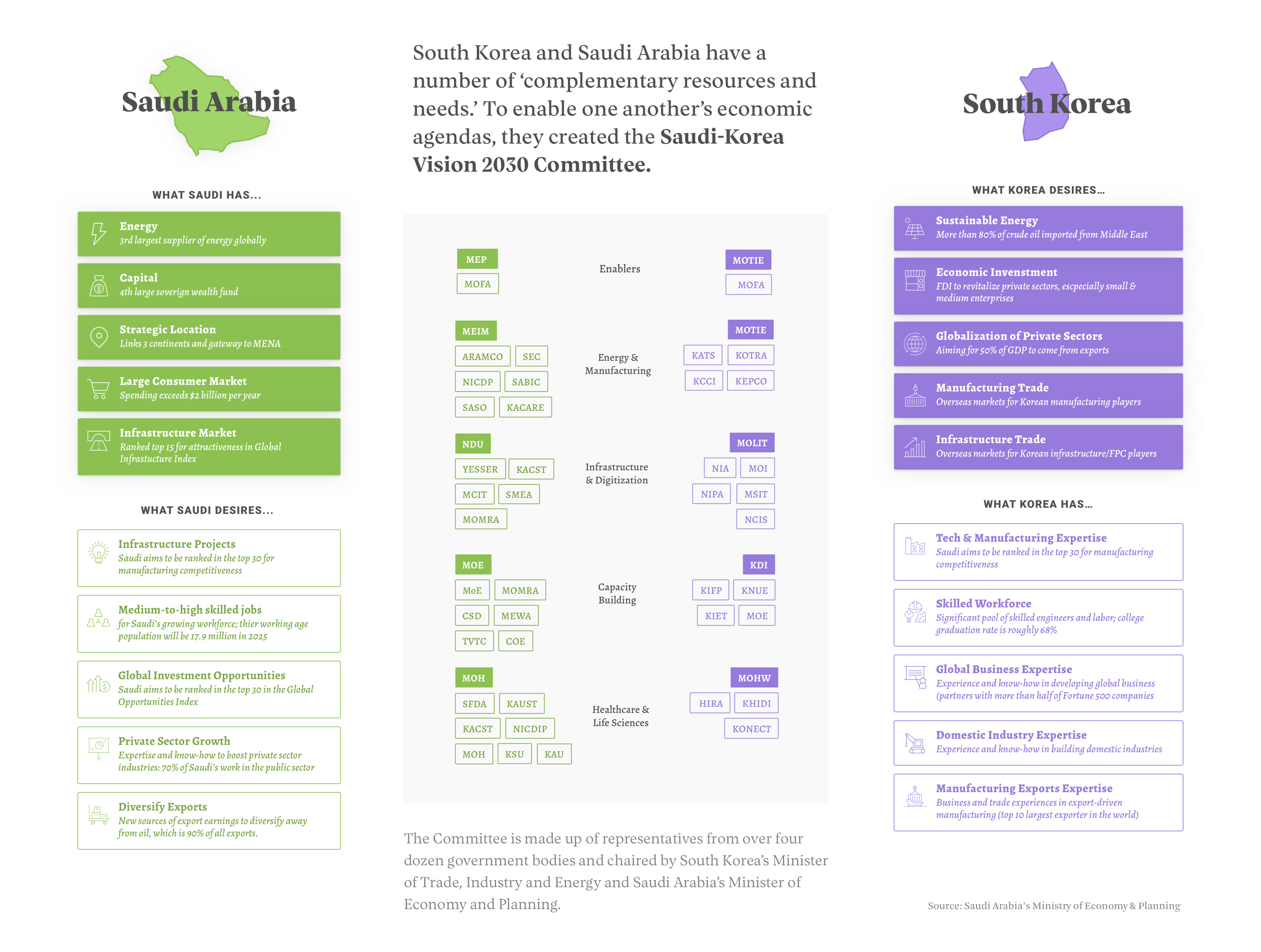

The Saudi-Korean Vision 2030

Since diplomatic relations were established in 1962, South Korea has had a long-standing partnership with Saudi Arabia in the energy, construction, and EPC sectors. Drawing on these strengths, South Korea and Saudi Arabia have elevated ties significantly in recent years. They established a formal strategic partnership to foster bilateral economic ties by launching Saudi-Korean Vision 2030 at a meeting held on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, China, in 2016. This bilateral initiative is meant to be compatible with the broad strategic framework of Saudi Vision 2030, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s blueprint to transform Saudi Arabia’s economy. It aims to expand infrastructure, manufacturing, and technology industries in both countries and promote foreign direct investment between the two countries. To manage 40 projects under this initiative, the two governments formed the Saudi-Korean Vision 2030 committee, which is divided into five subgroups: energy and manufacturing, smart infrastructure and digitization, capacity building, healthcare and life sciences, and SMEs. Capitalizing on complementary strengths, Saudi-Korean Vision 2030 aims to improve South Korea’s energy security, increase FDI inflows, and expand South Korea’s overseas markets for manufacturing products and EPC projects. From the Saudi perspective, South Korea is a strategic partner for its ongoing efforts to enhance human capital resources and transform its economy through diversification. Discussions are also underway to strengthen cooperation in renewable energy, smart infrastructure, and digitization strategies.

Since the establishment of Saudi-Korean Vision 2030, South Korea has seen a rapid increase in bilateral visits and meetings with Saudi Arabia. In November 2018, President Moon met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Buenos Aires, Argentina, prior to the start of the G20 Summit. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman made his first official visit to South Korea in June 2019 and pledged to strengthen bilateral relations in the energy, automotive, health, and ICT sectors. The crown prince met with South Korean business tycoons during his visit, and the Saudi business delegation signed 16 MOUs with South Korea, including agreements on hydrogen energy and eco-friendly automobile technology. Following this visit, the Samsung Group signed a MOU with Saudi Arabia in October 2019 to develop a massive entertainment hub in Qiddiya by building a sports complex and becoming a technology sponsor, and the Saudi crown prince also met with South Korea’s National Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong-doo in Riyadh in November to discuss defense cooperation between the two countries.

The Saudi-Korean Vision 2030

South Korea’s Strategic Interests in Iran

The frequency of South Korea’s high-level exchanges with Iran accelerated during the Lee Myung-bak administration from 2008 to 2013. Park Geun-hye, his successor, became the first South Korean president to visit Tehran in May 2016. The joint statement on comprehensive partnership that was issued during Park’s visit highlighted bilateral cooperation in politics, economics, and people-to-people connectivity. This included discussions on holding high-level meetings annually, the formation of a joint economic commission, and strengthening cooperation in the emerging fields of public health and education. However, the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, the Iran nuclear deal) and the elimination of sanctions waivers for Asian and European markets were major blows to the Iranian economy and to Iran-ROK ties. As one of the primary importers of Iranian oil, South Korea ramped up its purchases and became the second-largest importer of Iranian oil in March 2019, prior to the expiry of the sanctions waiver. Unfortunately, heightened geopolitical tensions between the United States and Iran have complicated bilateral ties further. The oil tanker and oil refinery attacks in Fujairah and Saudi Aramco in 2019 and the assassination of former Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps commander Qassem Soleimani by the United States in January led to a further ramping up of U.S. sanctions on Iran. Already debilitated by sanctions, Iran’s economy was damaged further by COVID-19, dimming even more the prospects for restoring the previous level of ROK-Iran bilateral trade and economic cooperation. Moreover, South Korea’s attempts to send COVID-19 testing kits to Iran as a diplomatic gesture had been impeded by U.S. sanctions. Although South Korea’s bilateral engagement with Iran continues to be constrained by sanctions and the diplomatic gridlock surrounding the Iranian nuclear program, South Korea has been able to simultaneously maintain close relations with Iran and the latter’s adversaries in the region by strengthening bilateral economic partnerships and remaining politically neutral. As a middle power, South Korea’s strategic interests in the region mainly lie in ensuring continued access to the region’s construction market and hydrocarbon resources to support its advanced manufacturing sector.

Given these constraints, South Korea has been scrambling to meet its energy needs by seeking alternative energy suppliers that would substitute for Iran, which was a major source of cheap crude oil. Despite the stifling effect on South Korea’s economy, Seoul has not had the diplomatic leverage to negotiate with Washington on extending a waiver on Iran sanctions, since the Moon administration is more concerned about North Korea’s nuclear program, an issue closer to home. Nonetheless, Tehran remains strategically important to South Korea based on geo-economic interests and both sides enjoy a prosperous relationship on the economic and cultural fronts.

South Korea’s Commercial Diplomacy with Iraq

According to Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Iraq is “the third-largest crude oil exporter to the ROK” and the “seventh-biggest cooperation partner in the construction and infrastructure sectors,” making it a vital economic partner. The post-conflict reconstruction of Iraq has been a fertile ground for construction and infrastructure projects for Korean firms. In 2008, the state-run KNOC concluded a $2.1 billion deal with the Kurdistan Regional Government for acquiring stakes in eight oil fields in northern Iraq. The former president of the Kurdistan regional government Masoud Barzani’s visit to Seoul in February 2008 led to the signing of a production-sharing agreement and South Korea embarking on two oil fields projects.

While South Korea has not shied away from forging partnerships with countries under post-reconstruction contexts or crippled by sanctions, the political, economic, and institutional impediments in Iraq are substantial. Some of the promise of the economic partnership has diminished due to political instability and financial troubles in Iraq. Several projects have been cancelled between 2016 and 2018, including the Sangaw South and Qush Tappa oil fields project, as South Korea was caught in a bureaucratic and political tug of war between the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan regional government. Moreover, the new $7 billion Karabala refinery project was grounded to a halt, as the Iraqi central government was unable to deliver the payments. Despite the losses it has incurred, South Korea has continued to seek stronger commercial ties, as Iraq has signed the third-highest number of EPC contracts with South Korea in the Middle East. To advance the relationship, President Moon Jae-in appointed Han Byung-do as his special envoy to Iraq. The Special Advisor to the President on Iraq led a delegation to Iraq in January 2019 that included senior Korean business leaders and officials from South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Ministry of Economy and Finance; the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport; and the Defense Acquisition Program Administration. Despite some remaining challenges, Iraq remains a strategic commercial partner for South Korea.

Strategic Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

The Moon administration is faced with tough political and strategic decisions in the Middle East. Given its dependence on Middle East energy, safeguarding shipping lanes in the Strait of Hormuz is critical to ensuring secure access to South Korea’s much needed energy supplies. However, what is often overlooked is that as a result of its increasing economic footprint in the Middle East, protecting South Korea’s 20,000-strong expatriate community in a geopolitically volatile region has become just as important for fostering its security commitment in the Middle East. The U.S. security retrenchment globally has made it all the more necessary for Seoul to step up to the plate, but Seoul is also hesitant to make any major commitments at the expense of irking its regional allies. As Korea’s economy is reliant on manufacturing industries, the rising tensions between the U.S. and China have had a debilitating effect on its economy.

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, since the beginning of this year, is an area of both challenge and opportunity for South Korea–Middle East relations. On the one hand, it caused delays in major oil and gas and EPC projects involving South Korean businesses; on the other hand, the pandemic has provided opportunities for South Korea to strengthen global health diplomacy in the Middle East. Based on extensive testing and contact-tracing methods, South Korea capitalized on its crisis management experience in the wake of COVID-19 and has recently started exporting COVID-19 test kits to eight countries, including the UAE. In March, Moon discussed international cooperation on COVID-19 with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman ahead of the G20 Summit scheduled to be held in Riyadh on November 21 and 22. South Korea’s priority in economic and energy cooperation in the region calls for a concerted response to COVID-19 with partnering countries in the Middle East.

Section Four

Security & Military Cooperation

Growing Arms Trade with the Middle East

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), South Korea was the tenth-largest arms exporter in the world in 2019. This is a recent development as South Korea’s volume of arms sales witnessed an upsurge of 143% over the past five years—the largest increase in the volume of arms sales for any country in the world between 2015 and 2019. In South Korea’s search for markets for its growing arms industry, the Middle East has emerged as a key market alongside Southeast Asia and South America. Based on SIPRI data, Turkey was South Korea’s biggest arms buyer in the world from 2000 to 2013. In the past decade, South Korea has found new arms markets in the region in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan.

Globally, the K-9 Thunder, which is a self-propelled 155-millimeter howitzer, is one of the most popular arms sold from South Korea, including to Turkey. Saudi Arabia, which is a newly emerging market for South Korean munitions, has bought Raybolt antitank missiles. South Korea’s participation in the International Defense Exhibition & Conference (IDEX), which is the only international defense exhibition in the MENA region, has been a major vehicle for promoting arms sales in the region. By 2019, 30 South Korean defense companies had showcased their munitions. In addition, Hyundai Heavy Industries was the first South Korean company to become an exhibitor in the Naval Defense & Maritime Security Exhibition (NAVDEX), which is held in parallel to IDEX, in Abu Dhabi. Most recently, Poongsan, a South Korean arms manufacturer, which was also an exhibitor at IDEX 2019, had exported $82.7 million worth of ammunitions to the MENA region by April 2020. South Korea’s arms trade with the Middle East is not one way. According to the Korea Defense Industry Association, Israel was South Korea’s third-largest supplier of arms (4.6%) after the United States (53%) and Germany (36%) between 2013 and 2017.

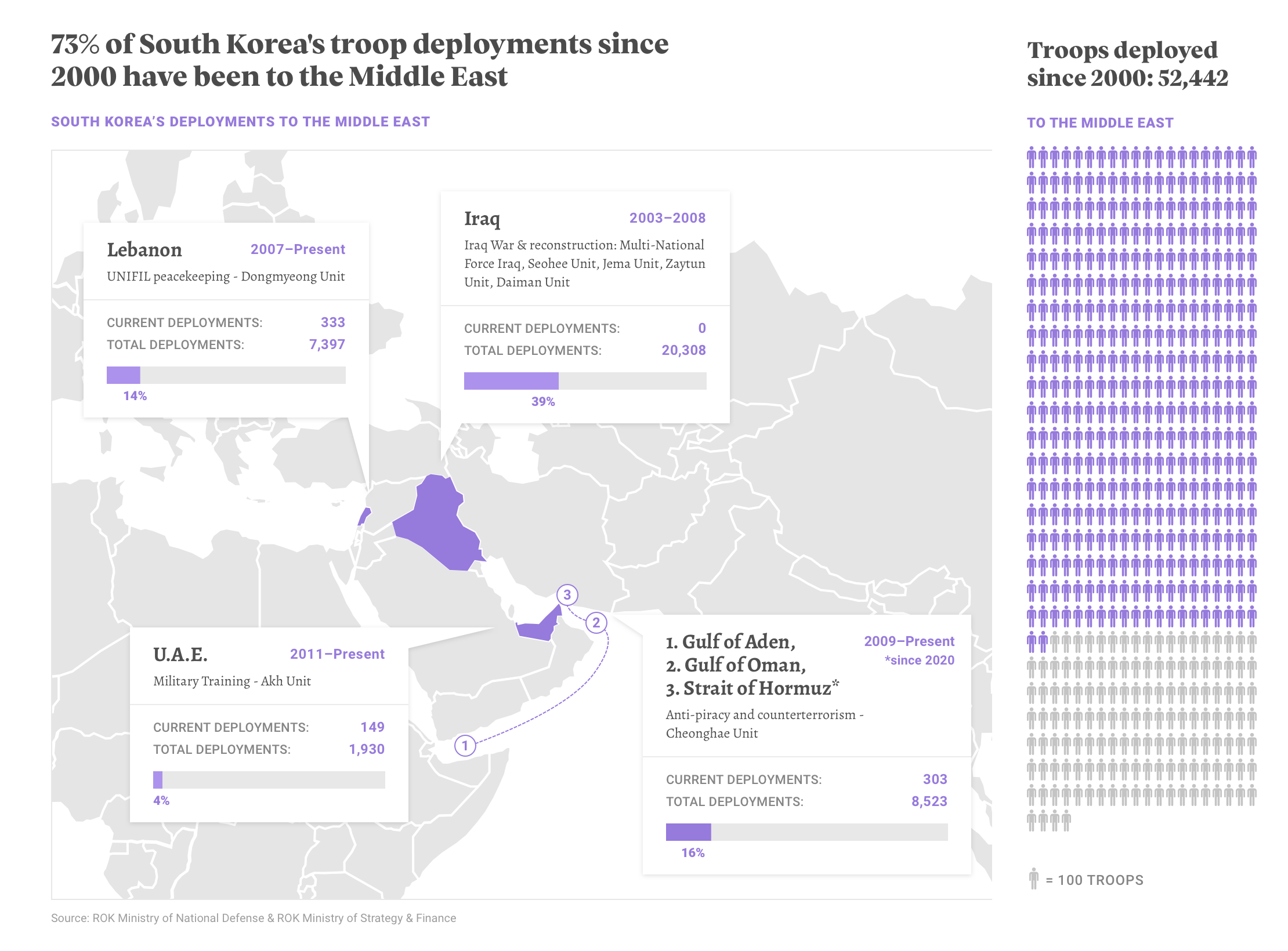

Defense and military-to-military cooperation are emerging fields of partnership between South Korea and the Middle East. Boasting the world’s sixth most powerful military, South Korea has become a rising player in the management of international security. It has done so by providing troops to UN peacekeeping and other multilateral operations as well by becoming a key arms exporter. The Trump administration’s America First policy and recent security challenges in the Middle East are pushing Asian countries like South Korea – which are dependent on Middle East energy – to mull playing a greater role in the provision of security in the region. This has posed political challenges for South Korean leaders, as it did during the Iraq War, because there is ample domestic concern about getting embroiled in Middle East security crises and a lack of appreciation for how stability in the Middle East is linked to prosperity at home.

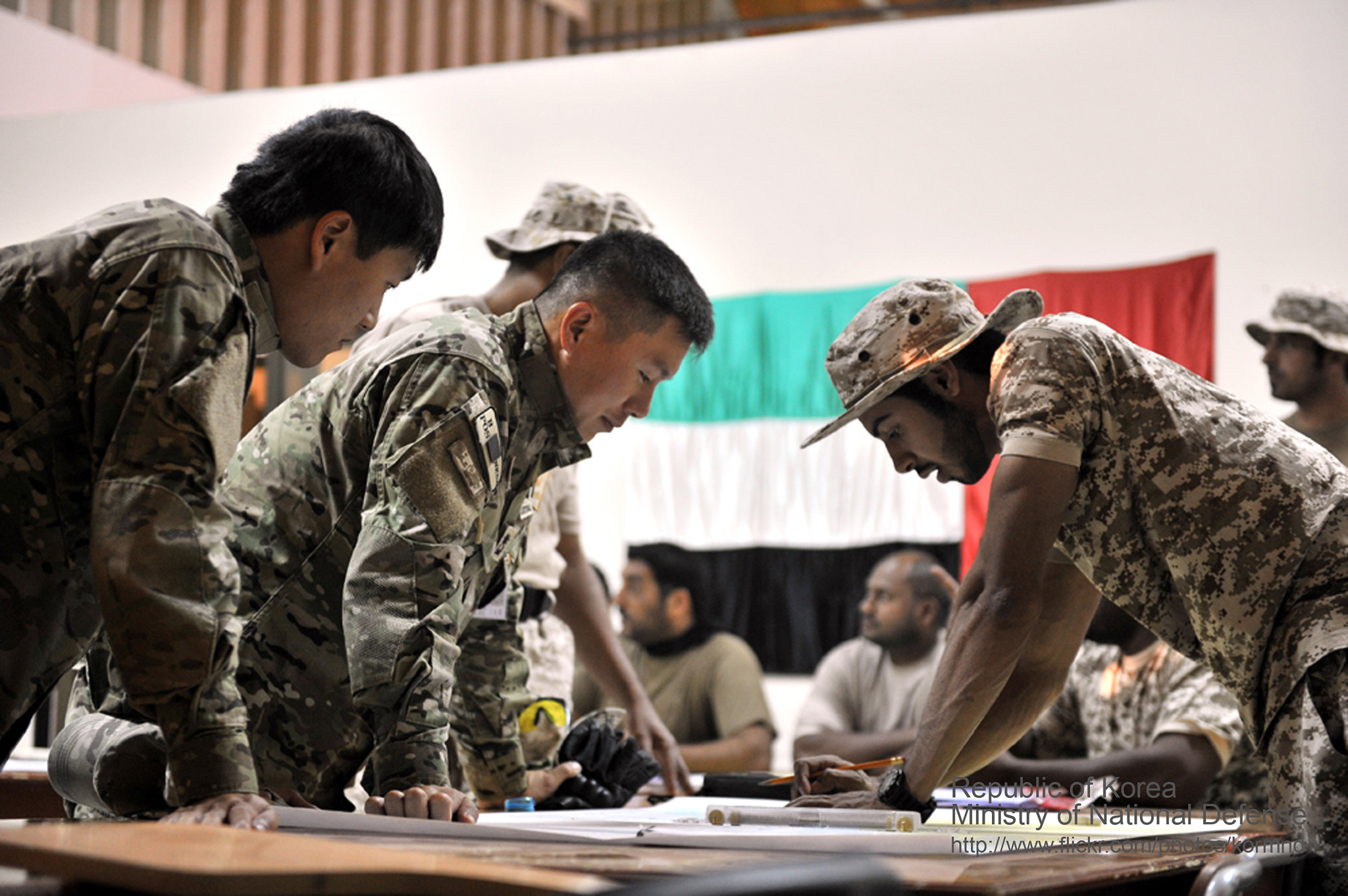

South Korea’s Deployments in the Middle East

South Korea has contributed to the management of peace and security in the Middle East through its troop contributions to UN and multilateral operations. South Korea dispatched army and air force units to Iraq and Kuwait between 2004 and 2008 to help with reconstruction efforts after the U.S. invasion of Iraq. And Seoul has been contributing peacekeeping forces to the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) since July 2007 and the Akh Unit to the UAE since January 2011. More recently, the South Korean Ministry of National Defense (MND) announced in January 2020 that the operational area of its Cheonghae naval unit, which has held naval exercises with the Combined Task Force (CTF)-151 for anti-piracy missions in the Gulf of Aden and the Gulf of Oman, would be expanded to the Strait of Hormuz. Although the United States pressured South Korea to deploy its troops to the U.S.-led maritime coalition, Seoul announced that it would deploy its naval unit to the Strait of Hormuz independently.

The decision elicited mixed reactions from the United States, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, and the MND took pains to emphasize that it was expanding the naval operations of the Cheonghae Unit rather than dispatching fresh troops to the area – further signaling the South Korean government’s hesitance to be seen as getting too involved in Middle East conflicts. The irony is that this deployment to the Strait of Hormuz, a vital choke point for global energy supply that also accounts for 70% of South Korea’s crude oil shipments, is strategically important to South Korea.

Apart from South Korea’s contribution of noncombatant troops to the U.S.-led international coalition in the Second Gulf War, one of South Korea’s earlier efforts to contribute to Middle East security was by contributing to Iraq’s reconstruction efforts. South Korea deployed the Zaytun Unit to the Kurdish district of Erbil, Iraq, from October 2004 to December 2008; it also deployed the 130-member Air Force Daiman Unit during the same period to transport supplies to the Zaytun Unit. During the four years the Zaytun contingent was stationed in Iraq, it was involved in Iraq’s post-conflict reconstruction efforts after the U.S. invasion in 2003. As part of reconstruction efforts, the Zaytun Unit built a library, schools, and water supply facilities, offered job-training courses to the Kurdish population, and provided job security to local teachers and to medical professionals by building a hospital. Socially, job training also helped equip and empower Kurdish women. Roughly 7,200 Iraqis benefited from these courses while the newly built hospital treated more than 88,000 soldiers, local Iraqis, and Korean expatriates. While participating in a noncombatant capacity, the South Korean government’s decision to send troops to Iraq initially drew domestic criticism due to misgivings about whether the mission would suggest a tacit endorsement of the U.S.-led invasion. The Zaytun Unit was the third-largest contingent of foreign forces in Iraq back in 2004, after the United States and the United Kingdom, until the South Korean government started retracting troops out of fear of a domestic public backlash.

The Dongmyeong Unit represents the longest-serving overseas deployment of South Korean forces. It has been contributing 7,300 forces to UNIFIL since June 2007 at the request of the UN, following the passage of UN Security Council Resolution 1701 and the approval of South Korea’s National Assembly. As of March 2020, 283 South Korean peacekeeping soldiers were part of the mission. Since the aftermath of the 2006 Lebanon War, UNIFIL projects have been mandated to support the activities of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) in Southern Lebanon, which includes conducting joint military exercises, carrying out daily patrols, as well as recovering infrastructure and destroying munitions and weapons from previous conflicts. As part of the peacekeeping mission, South Korean troops have been offering training to the LAF on counterterrorism tactics and techniques, patrolling techniques, self-defense tactics, as well as combat medical courses. Moreover, South Korean peacekeepers are involved in humanitarian initiatives such as provision of basic services and necessities, improving access to infrastructures, and providing medical and educational support. In April 2018, South Korean UNIFIL peacekeepers received UN medals in recognition of their service in South Lebanon.

The UAE is the only country in the world to which South Korea has deployed its overseas military contingent for bilateral defense and security cooperation. South Korea’s Akh Unit has been dispatching around 140 Special Forces soldiers to the UAE on a rotational basis since January 2011. The decision is based on the bilateral security cooperation agreement signed in May 2007 during the Roh administration. South Korea’s security cooperation with the UAE has had a synergistic effect on furthering bilateral cooperation in other fields, including the innovative priority sectors of nuclear energy, technology, space, and food/water security. Since then, the Akh Unit has committed to training UAE Special Forces as well as conducting joint military exercises. During President Moon’s visit to the UAE in March 2018, defense cooperation was identified as a top priority. Defense Minister Song Young-moo’s visit to Abu Dhabi in April 2018 has advanced this cooperation, as has the visit by UAE Crown Prince and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan to South Korea in February 2019.

Rising tensions in the Middle East between Iran and the GCC states and Iran and the United States have added pressure on South Korea to elevate its security commitments in the region. This became especially acute when President Trump explicitly called out Asian countries’ free riding on U.S. security provision in the aftermath of the tanker attacks in the Gulf of Oman. The deployment of the Cheonghae Unit is subject to renewal by the end of this year, making clear that South Korean policymakers will once again have to balance the real need to secure energy and trade flows with the possibility of facing domestic criticism for getting tangled in Middle East security.

Section Five

People-to-People Ties

As a middle power, South Korea has ridden the tide of the Korean wave (hallyu), the burgeoning popularity of South Korean culture globally since the 1990s, to greater global influence and stature. South Korean culture has been at the forefront of Seoul’s public and cultural diplomacy globally, ushering in an interest in Korean culture around the world. The Middle East is no different.

Cultural diplomacy was one of the defining pillars of the Park Geun-hye administration. Within the MENA region, the government first opened a Korean Cultural Center (KCC) in Cairo in October 2014 and then in Abu Dhabi in March 2016. The KCCs in these countries aim to promote Korean culture, history, and language to the local population by hosting cultural events. In both countries, the KCCs have regularly held language, cooking, and arts and crafts courses as well as hosting cultural events throughout the year to promote South Korea’s gastro diplomacy and cultural diplomacy. In the UAE, the Korean Film Festival is an annual event that showcases Korean films in a local cinema in Abu Dhabi. In addition, Korean clubs, which have formed across local universities since the late 2000s serve as avenues for promoting Korean culture in the UAE. The Park administration also inaugurated bilateral cooperation in the halal food industry with the UAE in March 2015. As a consequence, South Korea’s exports of agricultural products to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member countries increased by 8.8%, and the value of total exports amounted to $913 million by 2016.

The Korean-Wave (Hallyu) in the Middle East

Korean dramas Dae Jang-geum, Jumong, and Winter Sonata dominated TV ratings in Iran and Jordan, with all three dramas estimated to have reached more than 90% viewer rating in Iran. The concept of hallyu became internationally recognized around the time that the song “Gangnam Style” by PSY went viral online and became the most played video in the world, reaching 1 billion views on YouTube in December 2014. By 2013, PSY’s music video had 42.17 million views in Saudi Arabia alone, with another 4.8 million and 1.7 million views in the UAE and Kuwait, respectively. More recently, boy bands such as EXO and BTS have become K-pop sensations across the Middle East, particularly in Dubai and Saudi Arabia. The K-pop band EXO’s song “Power” was the first Korean song to be played at the Dubai Fountain (a tourist attraction) in February 2018, and both EXO and BTS were given a Dubai star in Dubai’s version of the Walk of Fame in July 2019. BTS not only became the first K-pop band to perform in Riyadh but was also the first foreign artist to perform a solo concert in Saudi Arabia.

In addition, the Korean movie industry recently gained a worldwide reputation through the movie Parasite, which won Golden Globe Awards and Academy Awards in 2020. The movie was premiered in Abu Dhabi by the South Korean embassy in the UAE to commemorate the milestone and premiered in UAE cinemas in January 2020.

In 2019, BTS not only became the first K-pop band to perform in Saudi Arabia but also the first foreign artist to perform a solo concert.

Rising Healthcare Cooperation and Tourism

Owing to the “hallyu phenomenon” and the global popularity of the Korean entertainment industry, cultural tourism is a promising industry in South Korea. Though the inflow of Middle Eastern tourists is moderate in absolute terms, the figures from the Korea Tourism Organization since 2004 suggest an upward trend. However, the number of Iranian tourists as a whole has greatly fluctuated and recorded a sharp decline, especially in the past two years, in part due to the collapse in the value of the Iranian rial against foreign currencies and renewed U.S. sanctions against Iran.

Healthcare is also a robust area of cooperation between South Korea and the Middle East. In 2011, South Korea signed a MOU with the UAE on healthcare cooperation; by 2018, the UAE had sent an estimated 8,000 Emirati patients to South Korea for medical treatment. In November 2012, Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) signed a MOU with the UAE Armed Forces on healthcare cooperation. ROK-UAE bilateral healthcare cooperation expanded after the signing of agreements in 2017 and 2018 on the training of healthcare professionals, collaboration in the health sector, and medical tourism. Notably, Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) has been entrusted with operating Sheikh Khalifa Specialty Hospital (SKSH) and training hospital staff after the hospital opened in December 2014. SNUH won the contract after competing against globally competitive hospitals including Johns Hopkins University Hospital and Stanford University Hospital in the United States and King’s College London Hospital in the United Kingdom. That operating agreement for SKSH was recently renewed in July 2019, a sign of success for bilateral health cooperation.

South Korea’s efforts to strengthen cooperation in the healthcare sector with the Middle East, which entails training medical professionals, building hospitals, and promoting the South Korean healthcare system and medical equipment, have also extended to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Iran. In December 2017, South Korea signed a MOU with Iran on healthcare cooperation and agreed to build three hospitals in Iran. In January 2019, the South Korean Minister of Health and Welfare Park Neung-hoo returned from a three-day trip to the UAE and Qatar. During his visit to the UAE, Minister Park had the opportunity to introduce Korean medical equipment and the Korean health insurance screening system to the Saudi Health Minister Tawfiq Al Rabiah at the Health Medical Exhibition 2019, which was held in Dubai. In Qatar, the minister attended the Korea-Qatar Healthcare Symposium alongside medics from South Korea and Qatar, and the symposium was designated as a compulsory course for the Qatari medical professionals. By 2019, South Korean–Qatari cooperation in the healthcare industry was also extended to the military by launching the Qatari-Korean Health Conference and the Qatari-Korean medical exhibition, both under the patronage of the Qatari Armed Forces Medical Services Command.

Number of Middle Eastern Tourists Visiting South Korea

Section Six

Conclusion

South Korea’s ties with the Middle East have undergone rapid growth and transition since the Roh Moo-hyun administration took office in 2003. South Korea’s public diplomacy and soft power projection in the Middle East have blossomed via hallyu in recent years. Policymakers have made a conscious effort in that time to expand long-standing cooperation in the energy and EPC sectors to new areas such as defense and healthcare.

Though the Moon administration has been emboldened by its recent landslide victory, it faces difficult challenges ahead on multiple fronts—including the economy, nuclear energy policy, and geopolitics—that will impact the trajectory of ROK–Middle East relations in the years ahead. Over the past few years, South Korea has ventured into promising areas in the region – from arms trade and medical tourism to the halal food market – but connections and partnership in these spheres remain nascent. Continuing to build on such initiatives will require continued diplomatic engagement as well as economic stability and prosperity on both sides. However, due to COVID-19, South Korea’s economy is projected to experience the sharpest GDP contraction since 2008. This is further exacerbated by the potential risks of prolonged tensions between the United States and China. The trends discussed in this essay, especially in the economic and people-to-people spheres, will suffer a steep drop in 2020. But South Korea’s energy dependence on the Middle East as well as more robust partnerships in sectors such as technology and healthcare should provide a strong foundation for South Korea to continue to strengthen its ties with the region.

South Korea’s energy imports and EPC markets in the Middle East are mostly concentrated in the Gulf states, where economic and political conditions are relatively stable. However, South Korea’s geo-economic and energy security interests in the region are tremendous and are increasingly vulnerable given the rise in tensions in the region. The civil war in Yemen, Iran’s military activities, and the U.S. maximum pressure campaign on Iran have heightened tensions to a new level. At the same time, the Trump administration’s insistence that it cannot be the sole security provider safeguarding shipping lanes and energy corridors has raised alarms across Asian capitals, including in Seoul. As South Korea increases its strategic and security engagement in the region, it will also have a harder time navigating regional rivalries while staying neutral, as it has thus far attempted. Already, the Moon administration has had to toe the U.S. line on Iran despite South Korea’s earlier attempts to build up that bilateral relationship. The handwringing over the decision to expand the operations of the Cheonghae Unit to the Strait of Hormuz is another case in point. At home, South Korean policymakers are also faced with the challenge of convincing the public about the overriding importance of South Korea’s energy security and geo-economic interests. The renewal of deployment pending at the end of the year would be another trial period. This will be an ongoing challenge for Seoul over the coming decade as its economic partnership with the region continues to blossom.

Hae Won Jeong is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at Abu Dhabi University in the UAE. She is the author of the forthcoming book “South Korea’s Middle Power Diplomacy in the Middle East: Development, Political and Diplomatic Trajectories”. Jeong's research focuses on the nexus of nation-building, foreign policy and public diplomacy of the Arab Gulf states and wider West Asia, comparative political sociology, and Asia-Middle East relations.