Japan

JAPAN'S EVOLVING TIES WITH THE MIDDLE EAST

Christopher Lamont

July 28th, 2020

“Japan and the Middle East will make yet another leap beyond our business-centric connections by strengthening our ties in politics as well as in security.”

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

Section One

Overview

The pace and scope of Japan’s diplomacy in the Middle East have expanded over the course of the past decade. Tokyo has long viewed the region’s vast energy resources as vital to fueling the nation’s economic growth; recently, however, Japan’s ties with the Middle East have both deepened and grown more complex. Japan has harnessed its industrial and technological know-how to establish itself as a critical partner for major regional powers, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Thus, not only is Japan a valued market for energy exports, it is also an important partner in a wide range of sectors, from emerging technologies to space exploration.

The Japan-U.S. alliance remains the bedrock of Japan’s national security strategy and informs Japan’s engagement with the Middle East. In 2008, it appeared that Japan was coming into closer alignment with the United States in the region. With Japan having deployed Self-Defense Forces (SDF) troops to assist in refueling operations for the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan and having provided reconstruction assistance in Iraq, Japan appeared in lockstep with U.S. security preferences in the region. However, today, Japan is much more reluctant to be seen as outwardly participating in U.S. military operations in the Middle East. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was returned to office a second time in December 2012, has recalibrated Japan’s embrace of Washington’s priorities in the region and embarked on setting a more independent course in the pursuit of Japan’s interests. Japan’s latest SDF deployment to the Gulf of Oman in early 2020 highlighted this new course in practice, as Japan did not formally join the U.S.-led multinational maritime security mission to secure commercial shipping lanes in the Strait of Hormuz.

Japan’s diplomatic approach to the region, which emphasizes Japan as an “honest broker,” is crucial to understanding how Japan pursues its interests in the Middle East. Japan’s regional engagement is often understood as a delicate balancing act between the overriding imperative of maintaining a strong security alliance with the United States on the one hand and not putting Japan’s energy and economic ties at risk by antagonizing regional capitals on the other. While Tokyo certainly is highly sensitive to Washington’s foreign policy preferences in the region, this narrow focus on balancing U.S. preferences versus Japan’s energy interests obscures Japan’s growing diplomatic, economic, and cultural outreach in the region. Japan’s interests in the Middle East are far greater and more diverse today than they were 10 years ago.

Japan’s Middle East priorities are in line with Tokyo’s broader strategic goal of managing its relationships and growing its influence in the context of a more assertive China and growing uncertainty over the future U.S. role in the Middle East. Tokyo is cautiously charting a more independent course by building relationships to secure Japanese interests in the face of China’s growing regional footprint. Therefore, in redefining Japan’s own role, Abe prefers to put an emphasis on how Japan’s approach to the region differs from that of Tokyo’s competitors and the added value that a strong relationship with Japan can bring to the region.

Section Two

Economic & Energy Ties

Energy has long dominated Japan’s economic ties with the Middle East and that remains the case today. As of 2017, petroleum still accounted for more than 90% of the total value of imports into Japan from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar. However, both Japan and its Middle Eastern partners have taken steps to broaden their economic ties and expand trade relationships beyond energy resources.

Japan is the world’s fourth-largest importer of oil, and as of 2017, Japan was the second-largest export market, behind China, for Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar. On the other hand, the Middle East, as a market for Japan’s exports, remains small compared to Japan’s two biggest export markets, the United States and the European Union. Nevertheless, the Middle East is an important market for Japanese automobiles and machinery. The top destination in the region for Japan’s exports is the UAE, with exports valued at $7.18 billion in 2019. The second-largest export market for Japan in the region is Saudi Arabia, which accounts for $5.11 billion in exports. The UAE and Saudi Arabia also host the most commercial locations abroad registered to Japan-affiliated companies according to data published by the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO).

As of 2020, Japanese companies have been active in oil exploration and production throughout the Middle East. Today, one of Japan’s largest oil development and production projects is the Japan Petroleum Exploration Co. (JAPEX) Garraf Oil Field in southern Iraq. In a consortium with PETRONAS of Malaysia, JAPEX won the Garraf Oil Field contract in December 2009. Oil production at the field began in 2013; as of 2019, production volume at the field averaged approximately 90,000 barrels per day. The plan, prior to COVID-19, was to increase production to 230,000 barrels per day by the end of 2020. Also in Iraq, Japan has recently approved an approximately $1 billion loan through the Japan International Cooperation Agency for the Basra Refinery Upgrade Project II in southern Iraq. It was the largest project funded by a $3.6 billion loan package to finance projects in Iraq’s oil and gas sectors.

Japan had been Iran’s second-largest trade partner after China in the 2000’s; however, in 2010, Japan took a step back due to U.S. pressure in light of Iran’s developing nuclear program. In 2010, Japan’s total exports to Iran were valued at more than $2 billion, whereas in 2019 Japan’s exports to Iran had fallen to just $66 million. Meanwhile, for comparison, Japan’s exports to the UAE in 2019 were valued at $7.18 billion.

Japan’s past experience in Iran allowed Tokyo to quickly capitalize and jumpstart commercial ties with Iran once the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was secured in 2015. The Japan-Iran Investment Agreement was signed in early 2016 to facilitate the return of Japanese investment and businesses to Iran. Japanese companies, such as Mitsubishi and Toyota, were among the first to enter the Iranian market after the JCPOA took effect, and many more Japanese companies signaled an interest in Iran. With Tokyo underwriting some of the financial risk, it appeared that Japan-Iran trade relations were on the cusp of expanding. By 2017, the value of Japan’s exports to Iran had risen back to almost $1 billion, and serious discussions over the purchase of aircraft, major infrastructure projects, and investment in Iran’s energy sector had all taken place.

The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the JCPOA in May 2018 and its pressure campaign on Tokyo and other capitals to halt trade with Iran effectively froze Japan-Iran economic ties for the second time in a decade. This led to a retreat of Japanese firms from the Iranian market and a move to source oil from alternative sellers. Although Japan initially secured a waiver from Washington in November 2018, allowing Tokyo to continue to import Iranian oil, this waiver was not renewed in May 2019, bringing an end to Japan’s imports of Iranian oil. In 2008, Iran was Japan’s third-largest oil exporter; however, by 2020, oil exports from Iran had all but stopped.

The Middle East Is Critical to Japan’s Energy Security

Tokyo believes its energy dependency on Middle Eastern oil will last beyond 2030, when Tokyo expects oil and natural gas needs to decrease to account for about 40% of Japan’s energy needs compared to about 62% as of 2019. Despite being resource-poor, Japan possesses a significant amount of oil storage capacity and has allowed countries from the Middle East to store oil in Japan for distribution elsewhere in East Asia. Japan has also made arrangements with countries to share its emergency reserves in the event of a major supply disruption. As of October 2019, Japan’s total petroleum reserves contained 515.64 million barrels, or the equivalent of 234 days of consumption. The Middle East is a critical partner for Japan in this endeavor. In January 2020, Japan and the United Arab Emirates signed the UAE-Japan Strategic Energy Cooperation Agreement that extended an agreement that allowed Japan to store 8 million barrels of UAE crude oil to give the UAE easier access to East Asian markets, while also augmenting Japan’s strategic oil supply in the event that energy supply routes were disrupted. Japan also has a similar arrangement with Saudi Arabia and has entered into an agreement to hold a portion of Australia’s strategic oil reserve. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a gap was exposed in Japan’s energy supply chain, as it was revealed that Japan’s major shipping companies Mitsui, Nippon Yusen, and Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha did not have large enough shipping fleets to take advantage of the demand for tankers on spot markets to warehouse crude.

In addition to its storage capacity, Japan also enjoys significant, and growing, refining capacity. Japan has a total of 23 active crude oil refineries, of which Negishi, Yokkaichi II, and Kawasaki are expected to become the nation’s largest refineries over the next three years with total refining capacities of 2.7 million barrels per day, 2.55 million barrels per day, and 2.35 million barrels per day, respectively, by 2023. However, Japan’s refining sector is highly vulnerable to disruptions in imports of Middle Eastern oil, and Tokyo has also sought to diversify its energy mix by investing in liquified natural gas (LNG) to reduce Japan’s dependence on Middle East oil.

Japanese Affiliated Companies in the Middle East

Japan's Energy Mix and Imports From The Middle East

Beyond Oil for Land Cruisers?

Japan has flexed its muscles in recent years to nurture Japan–Middle East business and investment ties through a number of high-profile seminars and events hosted in Tokyo and across the region. Among these was the first Japan-Arab Dialogue Forum in 2017, the Japan-UAE Business Forum in 2018, and the Saudi-Japan Vision 2030 Business Forum in 2019. Japan also planned a wide-ranging exhibit of Japanese technology and tourism at the 2020 Dubai Expo as part of the Japan Pavilion, prior to the expo’s postponement due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the cliché of an oil-for-automobiles relationship remains very much alive. Japan–Middle East trade has been dominated for decades by oil being shipped east and automobiles shipped back west. A more recent variant of this cliché described Japan’s trade relationship with the Middle East as an “Oil for Land Cruisers” arrangement. In October 2019, Japan’s Defense Minister Taro Kono acknowledged that Japan buys a lot of oil from the Middle East and exports a lot of Toyotas, but the relationship should go beyond that.

Japan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have seized upon this challenge in recent years. The growing interest in the Middle East and Tokyo to diversify their trade relationships also highlights how Japan’s economic and energy ties with the Middle East have had to contend with the growing presence in the Middle East of Japan’s East Asian neighbors, South Korea and China.

One sector where change has been observed is investment in Japan by Middle Eastern investment funds. In October 2018, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund announced its second $45 million investment in the Japanese tech firm SoftBank’s Vision Fund, which counts Saudi Arabia as its single largest investor. SoftBank, under Masayoshi Son, was an attractive target for Saudi investment because Son’s Vision Fund’s focus on funding new and innovative technologies closely aligned with Saudi Arabia’s desire to secure a more prominent role in knowledge-intensive industries. However, in 2020, reports emerged that SoftBank’s Vision Fund had suffered significant losses.

As part of Japan’s effort to bolster Tokyo’s standing as a major global financial center, it has also lobbied hard for the Tokyo Stock Exchange to be the site of Saudi Aramco’s overseas listing. As of September 2019, it appeared that Tokyo was Saudi Aramco’s preferred choice; however, these plans had initially been said to have been put on hold due to an attack on the Abqaiq oil-processing facility in eastern Saudi Arabia on September 14, 2019. Later, there was speculation that Aramco’s listing on international markets might be further delayed due to increased volatility in energy markets. More recently, the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020 will likely throw these plans into greater uncertainty.

Investors in Japan's SoftBank Vision Fund

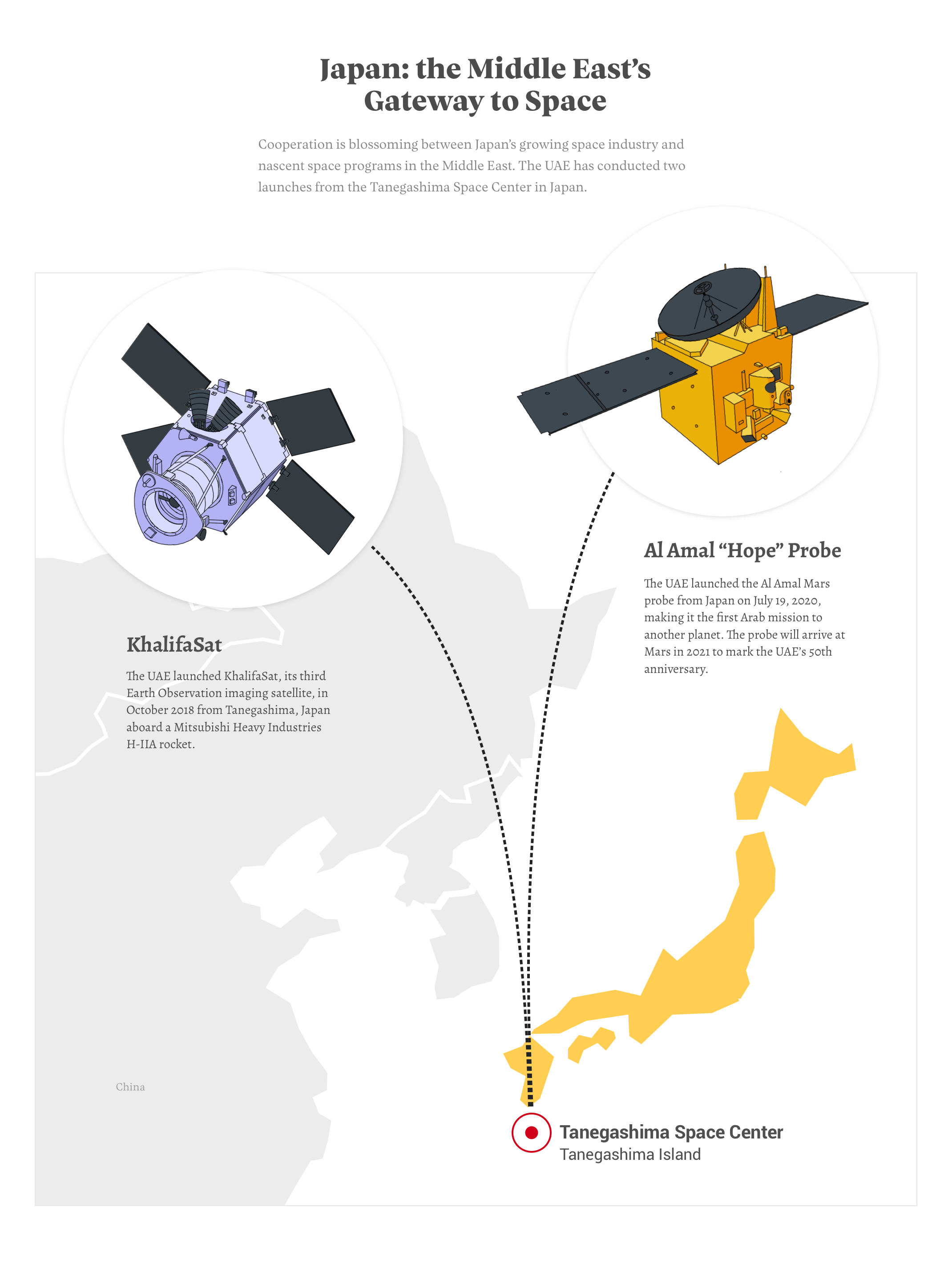

Japan as the Middle East’s Gateway to Space

Japan has been promoting its growing domestic space industry overseas, and the Middle East has been no exception. Japan has been involved in promoting satellite development and launches for a growing number of Southeast Asian countries. Prime Minister Abe pledged to double the size of Japan’s space industry by the early 2030s to $21 billion USD. Until just a couple of years ago, up to 90% of Japan’s space industry’s demand came from the Japanese government. Abe aims to change this and has directed Japan’s space agency to work more closely with the private sector. Japan, Abe hopes, will become a strong player in the satellite launch industry. In terms of revenue, the global earth observation satellite, data, and service market generated $7.17 billion USD in the year 2018 and is expected to continue to grow at a rate of 9.10% from 2018 to 2023. While this market has traditionally been dominated by North America, the greatest future growth is expected to be in the Asia-Pacific.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), alongside its partners in industry, has established Japan as a key player in the global space marketplace. JAXA benefited from Tokyo’s prioritization of Japan’s space industry in its diplomacy and foreign relations through the acquisition of a growing number of international projects. In the Middle East, JAXA collaborates with the UAE’s Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC). As part of this deepening cooperation with the UAE on space, Japan, along with South Korean know-how, launched the UAE’s first domestically assembled earth observation satellite, KhalifaSat, in 2018. This was followed by Japan’s launch of the UAE’s Mars-bound Amal probe in July 2020.

Section Three

Strategic & Diplomatic Relations

As Japan faces growing competition from China and South Korea in Middle East markets, the pace and scope of Japan’s diplomacy in the Middle East have steadily increased. Numerous visits to regional capitals by Prime Minister Abe and other senior government officials attest to this, as do the increasingly frequent and high-level visits to Japan by Middle Eastern leaders. However, it would be a mistake to view Japan’s diplomacy as narrowly promoting a mercantilist agenda or reflexively serving U.S. interests in the region. To continue to be perceived as an honest broker and to secure Japanese interests in a region where China’s footprint is growing, Japan has been careful not to be seen in Tehran as too closely aligned with U.S. interests in the region. Japan has also become a significant contributor to humanitarian efforts, from supporting reconstruction and development in Iraq to providing humanitarian assistance for refugees fleeing from the war in Syria. In addition, Japan has flexed its diplomatic muscle in conflict mediation efforts to reduce tensions in the Gulf. In 2019 and 2020, Prime Minister Abe sought to leverage Japan’s relationships in the region to reduce escalating tensions between the United States and Iran. In addition to these efforts, Japan has navigated the cultivation of closer ties with Israel, while also maintaining a commitment to a two-state solution for Palestine. Overall, Japan’s strategic outreach to the Middle East can be seen as consistent with a broader strategic vision in Tokyo to strengthen a rules-based international order.

Prime Minister Abe’s diplomacy toward the Middle East is largely consistent with that of previous governments in Tokyo, which balanced Japan’s own interests with U.S. preferences. It was Prime Minister Yuichiro Koizumi who broke from this practice in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the United States by openly aligning Japan’s foreign policy in the region with the U.S. Global War on Terror. Abe, on the other hand, has been much more cautious in deploying the SDF to the Middle East, instead pursuing policies aimed at reinforcing the image of Japan as a more neutral broker in the region. To be perceived as a partner in the Middle East, Tokyo is aware that it cannot be seen by Tehran as being in lockstep with Washington. Japan’s complex web of relationships reflects Japan’s attempt to strengthen its ties across the region. Two of Japan’s most important relationships are with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Japan also enjoys warming relations with Israel and has expended a great deal of diplomatic capital, in terms of bilateral visits and facilitating mediation efforts, to maintain ties with Iran over the past few years.

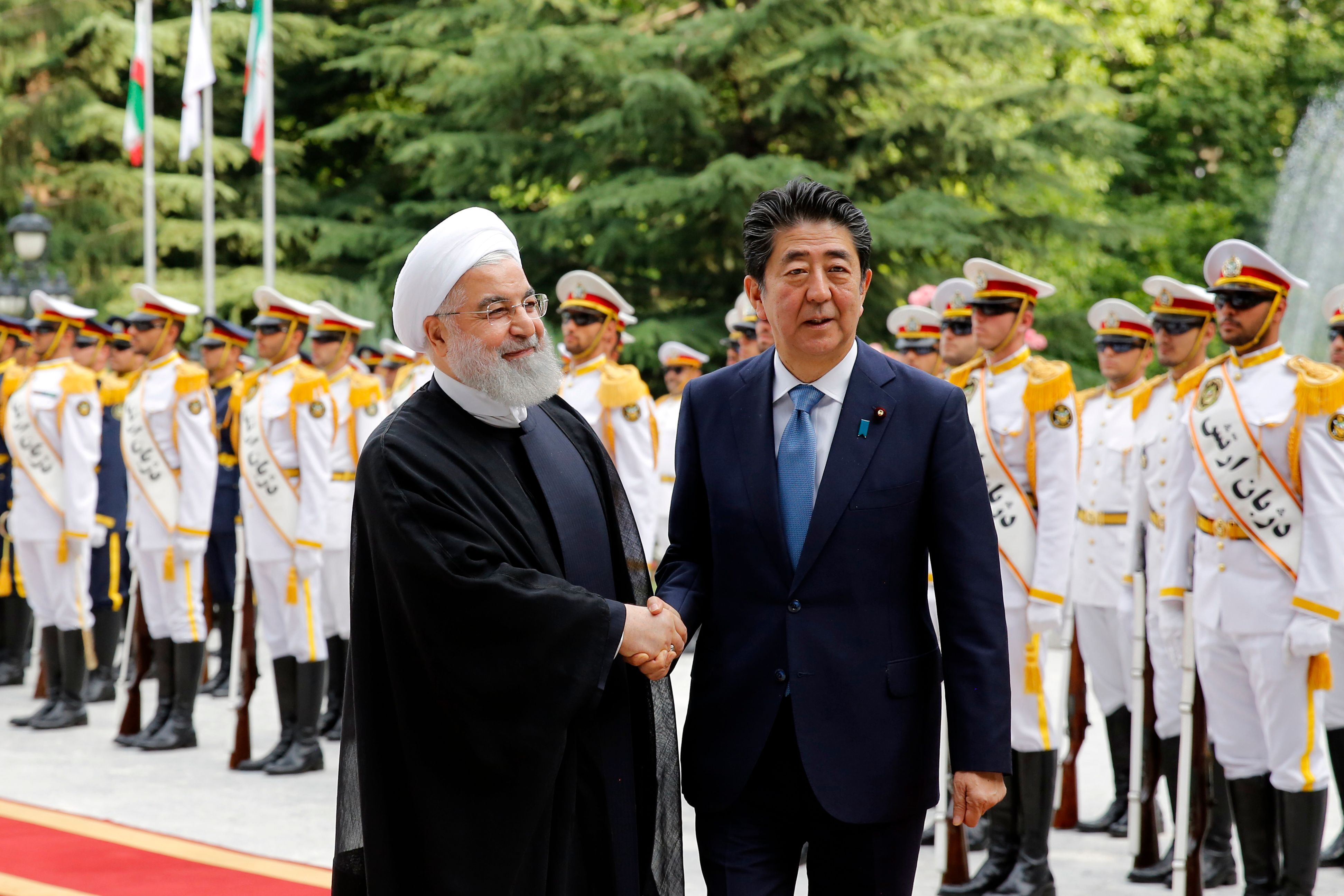

The growing importance Japan attaches to its Middle East relationships today is illustrated by the number of times senior government ministers from Japan visited regional capitals in recent years. For example, Prime Minister Abe has conducted more visits to the Middle East than any previous Japanese prime minister; in 2019, Abe became the first sitting Japanese prime minister to visit post-revolutionary Iran.

JAPAN-MIDDLE EAST BILATERAL VISITS, JOINT EXERCISES, AND NAVAL DEPLOYMENTS

Promoting Japan’s Interests in the Middle East

Under Prime Minister Abe, Japan has increasingly charted an independent course for its policies toward the Middle East. Despite Abe’s reportedly good rapport with U.S. President Donald Trump, Japan’s interests in the Middle East do not align with the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” strategy pursued against Iran. However, this recalibration of Japan’s Middle East policies also preceded the Trump administration. Abe’s willingness to put an emphasis on articulating Japan’s own priorities in the region was visible during his January 2015 visit to Egypt, Jordan, and Israel/Palestine. Prime Minister Abe made clear in Cairo that Japan would build relationships with the region on its own terms. According to Abe, Japan’s policies toward the region would be guided by a three-pronged emphasis on harmony, collaboration, and coexistence.

While Japan does not have the hard power leverage in the region that other states can draw upon, its significant development and humanitarian assistance to the Middle East does win it significant influence. Japan provided $1.9 billion to assist refugees displaced by the war against the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. In 2018, Iraq received more than $474 million in assistance from Japan. Japan has also cultivated its image as an honest broker and a neutral power by emphasizing its lack of colonial history in the Middle East in contrast to other major players.

In 2017, Japan took part in the first Japan-Arab Political Dialogue hosted by the League of Arab States. At this event, Japan’s Foreign Minister Kono outlined what he referred to as the four “Kono Principles” to guide Japan’s policy toward the Middle East. The first of these principles was “intellectual and human contribution.” This referred to strengthening the bonds that had been created by more than 12,000 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) experts who had been dispatched to the region along with another 3,500 Japan Overseas Cooperation volunteers. The second principle was “investment in people.” Here Kono emphasized that Japan’s own development experience highlights the critical role played by education and its commitment to providing more assistance to promote education and human resources. The third principle, “enduring efforts,” was meant to signal that Japan’s commitment to the region was a long-term one. The fourth principle, “enhancing political efforts,” sought to convey that Japan hopes to play a greater political role in the region.

Japan's Official Development Assistance to the Middle East

Saudi-Japan Vision 2030

While the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia remains Japan’s top oil supplier and energy continues to dominate the Japan-Saudi trade relationship, Japan has sought to support Saudi Arabia in its ambition to transition to a post-oil economy. Japan’s support has been well received in Riyadh, and Japan is now described as a key “mentor” for Saudi Arabia in its quest to achieve energy transition.

In March 2017, King Salman bin Abdul-Aziz al-Saud became the first Saudi king to visit Japan in almost five decades. While his visit was largely symbolic, it was the size of King Salman’s delegation that highlighted the importance Riyadh put on its relationship with Japan. With more than 10 aircraft required to transport a delegation that occupied more than 1,000 Tokyo hotel rooms, it was clear that Riyadh was seeking to build lasting ties with Tokyo. During King Salman‘s visit, the Saudi-Japan Vision 2030 initiative was launched. This was developed along the framework of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s signature Saudi Vision 2030 initiative, which was launched the previous year. Saudi Vision 2030 aims to facilitate Saudi Arabia’s economic transition to a post-oil era through the diversification of its economy, including the promotion of knowledge-intensive industries. Saudi Arabia has identified Japan as a key player in helping enable that transformation.

However, the Saudi-Japan relationship has not been without turbulence. Bilateral ties have strengthened at a time when Riyadh’s policies have generated significant turmoil in the region and beyond. In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Yemen, Egypt, the Maldives, and Bahrain cut diplomatic ties with and imposed a blockade on Qatar, a state with which Japan enjoyed strong ties. The following year, in October 2018, Saudi Arabia was implicated in the murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Khashoghi’s murder generated a flurry of negative publicity for Saudi Arabia and led to many Western investors publicly shunning high-profile Saudi events, such as Davos in the Desert. Khashoggi’s murder also had ripple effects in Tokyo. It posed a dilemma for SoftBank, which relied heavily on investment from Saudi and UAE sovereign investment funds for its Vision Fund. While SoftBank’s chief operating officer pulled out of Davos in the Desert, SoftBank was represented at the event by other senior executives. And reportedly, Softbank’s CEO, Masayoshi Son, also traveled to Riyadh to meet separately with Mohammed bin Salman. Despite the turbulence of 2017–2018, by the time Japan hosted the 2019 G20 Summit in Osaka, it appeared that Japan-Saudi relations remained firmly intact.

A Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with the UAE

In terms of regional diplomacy, Japan’s relationship with the United Arab Emirates is perhaps its most important. In 2018, Prime Minister Abe and Sheik Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan recognized the importance of the partnership between the two countries in announcing the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Initiative (CSPI), which established a framework for deepening cooperation across 12 issue areas that spanned regional and international security to renewable energy and women’s empowerment. The CSPI is important because it establishes a framework for deepening strategic cooperation between the UAE and Japan. In the Middle East, Japan has a similarly broad framework for deepening bilateral relations only with Saudi Arabia within the scope of the aforementioned Saudi-Japan Vision 2030 initiative. With the UAE, there is a strong defense component to bilateral relations, and the CSPI contains specific commitments for defense and security cooperation. This includes the holding of security dialogues and cooperation in defense technology equipment and the facilitation of bilateral exchanges.

Prior to the deployment of Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Forces (MSDF) to the Gulf of Oman in 2020, Prime Minister Abe visited Abu Dhabi. In fact, Abe has visited the UAE three times: twice since he became prime minister for the second time in December 2012 and once during his brief premiership in 2007. In May 2013, Abe held meetings with Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan and Vice President and the ruler of Dubai Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum; they jointly announced a statement on the strengthening of the comprehensive partnership between Japan and the UAE toward stability and prosperity that ultimately would bring about the CSPI.

Growing Trade and Warming Relations with Israel

Historically, Japan had maintained its distance from Israel due to Japan’s dependency on Gulf oil and Israel’s rivalry with those nations. However, as ties between Israel and the Gulf have improved, Tokyo has also deepened its bilateral ties with Israel. Since 2014, there has been an uptick in trade and investment between the two countries following Japan’s e-commerce company Rakuten’s $900 million acquisition of Viber, which, while based in Cyprus, was founded in and also maintained its reasearch and development (R&D) in Israel. Japan’s companies have found Israeli tech firms especially attractive, as was illustrated by Sony’s $212 million acquisition of the Israeli-based Altair Semiconductor. Trade is on the rise – the value of trade between Israel and Japan rose by 20% to $3.5 billion between 2017 and 2018. A number of leading Japanese firms, such as Fujitsu, have also entered the Israeli market, and a number of leading Japanese firms have invested in Israeli-based R&D centers.

Japan’s growing trade ties to Israel have the support of Prime Minister Abe, who visited Israel in 2015 and 2018. Abe’s 2015 visit marked the first visit to Israel by a Japanese prime minister in about a decade, and Abe’s second visit in 2018 highlighted just how much relations had warmed between the two countries. In 2017, Japan concluded an investment agreement with Israel to facilitate a deepening of trade relations. Notably, Japan is an increasingly attractive trade partner for Israel at a time when activist boycott movements have mobilized in Europe and the United States.

Maintaining Japan-Iran Relations amid External Pressure

Japan’s relations with Iran date to 1929 when Tokyo dispatched its first legation to Tehran. In 2019, Japan and Iran marked the ninetieth anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two states. As such, Japan’s relationship with Iran is one of its longest standing in the region. When Iranian President Hasan Rouhani visited Tokyo in December 2019, he became the first Iranian president to visit Tokyo in almost two decades.

This long-standing relationship has faced significant headwinds over the past decade. In 2010, Japan curtailed its investment and trade with Iran in response to sanctions imposed over the Iranian nuclear program and pressure from the United States. However, while Japan withdrew from the Iranian energy market, China remained. In 2015, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) brought about a resurgence in Japan-Iran trade and investment that would be reversed following President Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the JCPOA in 2018. Japan has sought to salvage its relationship with Iran and mediate between the United States and Iran in the context of heightened tensions between the two states. Tokyo has had to balance the imperatives of maintaining a strong relationship with the Trump administration, while attempting to leverage its relationship with Iran to reduce regional tensions, which could put at risk Japan’s energy supplies and its economic and energy interests in Iran.

On June 13, 2019, the Kokuka Courageous, a Japanese-owned tanker, and a Norwegian-owned tanker were attacked in the Gulf of Oman. This attack coincided with Abe’s visit to Tehran, leading to speculation that the attack was launched to scuttle Abe’s mediation attempt. The attack had the effect of underlining the threat posed to Japanese shipping interests in the Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman and jump-started planning for the deployment of Japan’s most recent long-term military deployment to the region. Since then, Japan has also sought to provide humanitarian assistance to Iran in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2020, Japan announced that Iran would be among the 40 countries to which Japan would provide its COVID-19 treatment Avigan.

Section Four

Security & Military Cooperation

Japan’s 2019 Defense White Paper affirmed that the U.S.-Japan alliance continues to be the cornerstone of Japan’s national security. The three pillars of Japan’s defense identified in the report are Japan’s own defense architecture, the Japan-U.S. alliance, and international security cooperation. It is the latter two pillars that have led to Japan’s increasing involvement in security and military presence and cooperation in the Middle East.

In 2010, it appeared that Japan was coming into closer alignment with the United States in the Middle East and that the following decade would see Japan further relax its constitutional restrictions on the use of force to participate alongside the United States in shouldering the burden for regional security. With Japan having deployed the SDF to assist in refueling operations for the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan, and also more controversially to provide reconstruction assistance in Iraq, Japan seemed to be aligning with U.S. security interests in the region. However, Japan’s Prime Minister Abe, who returned to office a second time in December 2012, recalibrated Japan’s embrace of Washington’s priorities in the region. There was a growing recognition in Tokyo that aligning too closely with Washington’s diplomatic and security initiatives in the Middle East undermined Tokyo’s efforts to build relations on its own terms with regional capitals. However, Japan remains sensitive to Washington’s preferences. This tension between maintaining cordial ties with Tehran and supporting U.S.-led security missions was most recently illustrated by Japan’s SDF mission to the Gulf of Oman in early 2020. Japan did send forces to the region as President Trump urged; however, it did not formally join the U.S.-led multinational mission. Japan’s defense minister cited Tokyo’s desire to maintain friendly relations with Iran as the reason Japan chose to dispatch its own mission rather than join the U.S.-led coalition.

Japan’s relative lack of hard power levers limits the scope for security cooperation. This is not to say Japan lacks significant military capabilities, but rather that Japan cannot deploy these capabilities in a manner similar to that of China or South Korea. Nevertheless, Japan has set a record for defense spending over the previous eight years, with Japan’s latest defense budget totaling $48.56 billion.

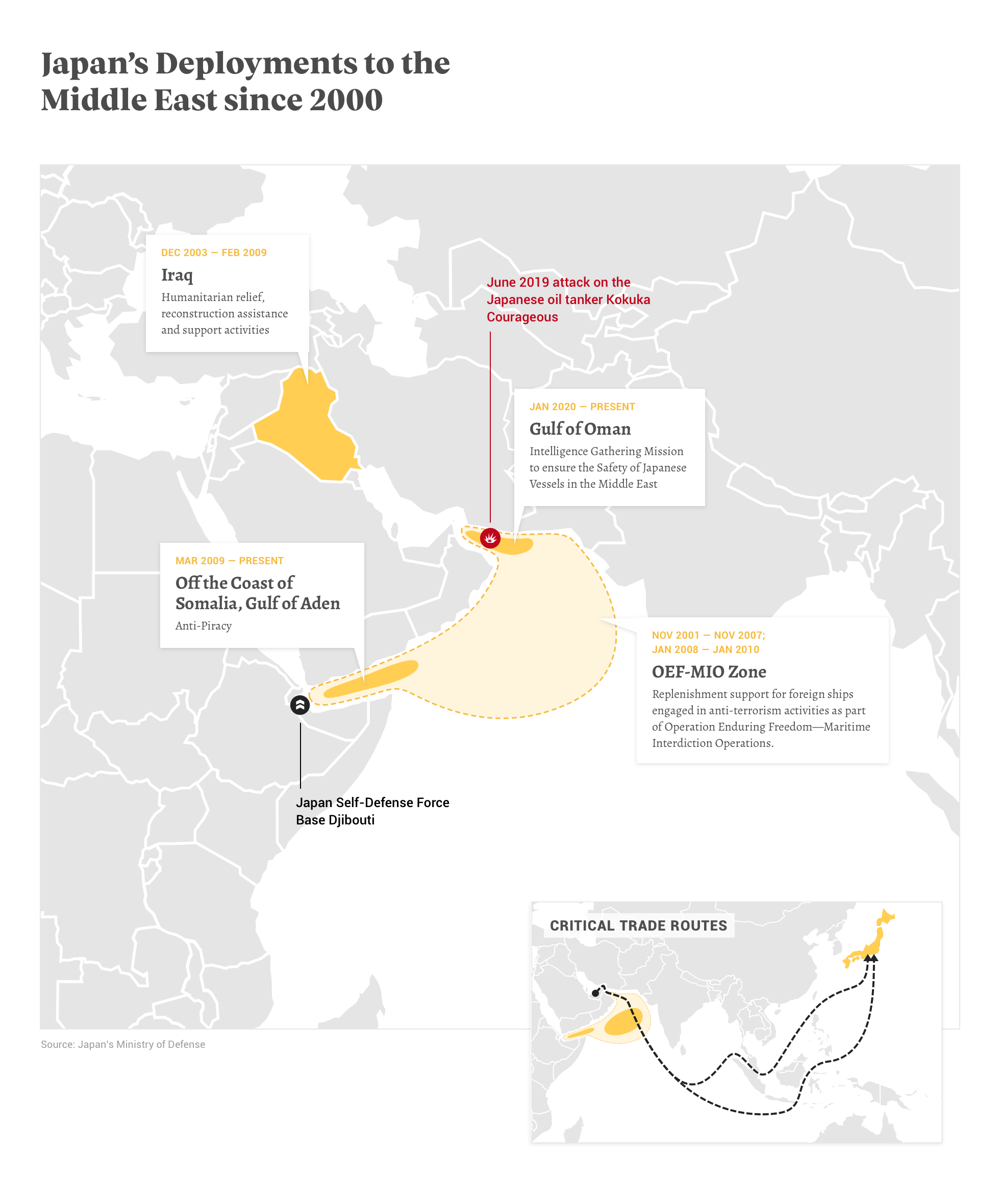

Japan does maintain a permanent security presence in the region. It has deployed various air and naval assets in Djibouti since 2011 and coordinates with capitals in the Middle East on SDF deployments. At the same time, Japan’s leaders must keep a close eye on the fact that SDF deployments to the region are unpopular at home. To convince a reluctant domestic audience to support Japan’s continued engagement with the region, Japanese leaders routinely emphasize national self-interest as the reason the SDF is deployed on far-flung missions. For example, Japanese leaders have stressed that they must deploy the SDF in the Middle East for the sake of energy security. Policymakers in Tokyo have tried to communicate to a skeptical public that given East Asia’s energy dependence on the Middle East more broadly, any disruption to shipping lanes would have severe consequences for East Asian regional security as well.

Japan’s Military Presence and Deployments in the Middle East

Japan established its first overseas base in Djibouti in 2009 to support a multinational anti-piracy mission off the coast of Somalia. Although Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Forces (MSDF) had been active in the Indian Ocean to provide assistance for the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan since November 2001, the Djibouti SDF base provided Japan with an important logistical hub for operations spanning Africa to the Middle East to Central Asia. The establishment of an overseas base marked a watershed moment for Japan, as Tokyo entered into its first Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) since World War II. The base quickly took on strategic importance that went beyond the original counter-piracy mission. It was used as a staging area for the evacuation of Japanese citizens from Juba, South Sudan, in 2016, and it provided Japan with the capability to carry out its mission in the Gulf of Oman in early 2020. As a result of the base’s strategic importance, Tokyo has expanded and upgraded it.

Japan’s SDF has participated in four major multilateral security and reconstruction missions in the greater Middle East. These include the MSDF mission to support the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan from 2001–2007, the SDF deployment to southern Iraq from 2003–2009, the anti-piracy mission off the coast of Somalia (2009–present), and the MSDF intelligence mission in the Gulf of Oman, which began in January 2020. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Koizumi, Japan launched two controversial missions that pushed the boundaries of constitutional restrictions on Japan’s use of force abroad in support of the U.S. war efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Originally, the SDF deployment to southern Iraq was officially a reconstruction assistance mission. However, as Iraq descended deeper into post-2003 invasion violence, Japan’s SDF found itself deployed in what was an increasingly dangerous environment. Koizumi broke with a decades-old precedent of not dispatching the SDF into ongoing armed conflicts. The MSDF mission in November 2001 in support of the U.S. war in Afghanistan marked the first time Japan deployed its military in support of ongoing combat operations.

In January 2020, Prime Minister Abe visited Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman. The main purpose of this visit was to secure diplomatic support for Japan’s deployment of an MSDF mission to the Gulf of Oman at a time of heightened tensions between the United States and Iran. That deployment may be a harbinger of things to come as the United States increasingly pushes its Asian partners to burden-share in the provision of peace and security in the Middle East. However, any future SDF deployments would require delicate balancing for Japan to maintain its relationships in Tehran and in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) capitals.

Japan’s Growing Security Interests in the Region

Japan is increasingly aware of the need to secure relationships in a pivotal region where U.S. commitment is wavering and Japan’s neighbors, South Korea and China, are increasingly active. Thus far, Japan has not sought out establishing any additional bases in the region beyond that in Djibouti. Japan has also not deployed any SDF units to conduct security training activities in the region analogous to South Korea’s Ahk Unit’s training mission in the UAE. In the coming decade, Japan’s comparative lack of security engagement is likely to come under significant pressure as China expands its footprint in the region. Japan will likely attempt to strengthen security ties with the Middle East in two spheres, arms trade and space cooperation.

The Middle East is starting to emerge as a potential arms partner for Japan. In April 2014, Japan lifted its decades-old ban on weapons exports. Although Japan is a latecomer to the arms trade and has yet to score any major arms deals, potential clients in the Middle East have expressed interest. Kawasaki Heavy Industries showed off its C-2 military transport aircraft at the 2017 Dubai Airshow, marking the first time Japan sought to secure foreign buyers for its military aircraft. Also in 2017, the UAE expressed interest in purchasing the C-2; however, the UAE’s involvement in the Saudi-led war in Yemen has raised questions in Tokyo as to whether such a deal would run afoul of Japan’s arms export legislation, which prohibits Japan from exporting arms to countries engaged in armed conflict.

In April 2020, Japan’s Diet adopted a law establishing the Space Domain Mission Unit within the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF). This new space unit is expected to become fully operational by 2023, and it signals Japan’s increased reliance on space systems. Japan’s space launch services are provided by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, using the H-IIA and H-IIB launch vehicles. Japan’s growing space capabilities may add a new dimension to military and security relations with the Middle East. In October 2018, a UAE earth observation satellite, KhalifaSat, was launched into outer space aboard an H-IIA rocket from the Tanegashima Space Centre in Japan.

Japan’s growing security role will certainty create complications for Japanese leaders at home. Japan’s deployment of SDF to the Middle East remains unpopular domestically. When Japan deployed its most recent mission to the Gulf of Oman in January 2020, polls showed that almost 60% of the public opposed this mission. As a result, Tokyo has sought to stress that such deployments are in Japan’s self-interest as 90% of Japan’s crude oil imports pass through the region. Whether or not the government’s messaging has been impactful will become clear if and when Japan finds itself confronted with or embroiled in a new crisis in the volatile region.

Section Five

People-to-People Ties

When Kono outlined his four principles for Japan’s policies toward the Middle East, it was clear that the focus was on building people-to-people ties. Unlike some of its Asian counterparts, Japan cannot draw upon large diaspora communities in the Middle East to build people-to-people ties. The largest Japanese community in the Middle East can be found in the UAE, where, as of 2017, more than 4,000 Japanese citizens are residents. Meanwhile, according to recent data, Israel hosts just over 1,000 Japanese residents, while Saudi Arabia is home to only 947 Japanese citizens. Given the relatively small size of Japanese communities in the region, Japan cultivates people-to-people ties through both official and semi-official channels. Japan relies heavily on contributions by JICA experts dispatched to the region and student exchanges with the Middle East to lay a foundation for strong and enduring ties.

Growing Educational Ties and Tourism

Education and language have become important tools in Japan’s soft power toolkit. In some countries, such as Iraq, Japanese diplomats have attracted a strong local following through their use of the Arabic language to address local audiences. Closer to home, the governor of Tokyo, Yuriko Koike, is an Arabic speaker who spent five years in Cairo. Koike continues to promote Japan’s ties to the Middle East and has been active in promoting the Saudi-Japan Vision 2030 initiative, speaking out on progress made on women’s empowerment in both Saudi Arabia and Tokyo.

Japan’s flagship government-funded scholarship program to bring international students to Japan’s universities is the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Technology’s (MEXT) Japan Study Program. In recent years, international education has become a more important part of higher education in Japan as international student numbers doubled from 2000–2009. With an increase from around 64,000 international students in 2000 to more than 134,000 in 2009, Japan saw the number of foreign students studying at its universities rise substantially in just a decade. The past decade has been consistent with this trend. The latest data show that as of 2018, almost 299,000 international students were studying in Japanese universities.

In 2009, only 923 students from the Middle East were studying at Japanese universities; by 2018, this number had risen to 1,457 students. However, when placed in the context of Japan’s overall international student community, the number of students from the Middle East remains comparatively small, representing less than 1% of Japan’s total international student population in 2018. Nevertheless, both Japan and Japan’s partners in the region have sought to bolster educational ties. In 2004, Minister of Higher Education and Scientific Research H.E. Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak Al Nahyan visited Japan and signed the “Memorandum of Cooperation on Higher Education and Scientific Research” with his counterpart Minister of Education Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Takeo Kawamura. And, consistent with Japan’s deepening economic and political ties to the UAE, interest in studying Japanese as a foreign language has also increased in the UAE. In 2019, the Japanese language was offered as a second foreign language at select UAE high schools.

Japan also enjoys an impressive degree of air connectivity with many countries in the Middle East, such as the United Arab Emirates, that has made tourism between the Middle East and Japan much more accessible. The Japan National Tourism Organization has identified the Middle East as an important international market. Overall, inbound tourism hasboomed over the course of the past three decades with an elevenfold increase in total numbers. Tourism from the Middle East has grown as well. Japan exempted UAE citizens from having to obtain pre-entry visas on July 1, 2017, making the UAE the only country in the Middle East other than Israel to enjoy visa-waiver travel to Japan. Taking North Africa into account, Tunisia is the only other country in the Arab world that enjoys visa-free travel to Japan. Given the recent UAE visa- waiver agreement, it is not surprising that Japan has emerged as a popular travel destination for UAE citizens in particular. According to a recent survey, 13% of UAE residents have visited Japan, compared to an average of 4% across the Arab world. Meanwhile, 80% of UAE residents expressed a desire to visit Japan. This suggests a strong foundation on which to grow tourism further. However, it remains to be seen how the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will impact Japan’s tourism industry, which has seen a more than 90% decline in inbound tourism when compared to figures from the past year.

Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike delivering a speech in Arabic at an Arab-Japan Day event on April 16, 2019.

Japan’s Growing Soft Power in the Middle East

Japan’s public diplomacy has contributed to reinforcing Japan’s positive image across the Middle East by promoting Japan’s technological and cultural capital. It is therefore not surprising that there is a growing interest in Japan within the region. Japan’s public diplomacy seems to have paid off as it is generally viewed positively in the Arab Middle East. A YouGov poll in 2019 of 3,033 Arab speakers from 18 Arab countries found that 56% of respondents identified Japan as an ideal mediator in the Israel-Palestine dispute. Japan’s positive image stems from a perception that Japan neither has designs to dominate the region nor is seen as playing a role in regional political entanglements.

Japan has become an attractive media market for international news agencies, with news media from Russia, Turkey, and France establishing Japanese-language services that have gained a significant following in Japan. In October 2019, Saudi Arabia entered the Japanese-language media market with its English-language newspaper Arab News. The Japanese-language site’s editor-in-chief stated that the aim of this new 24-hour online news service was to provide a blend of coverage of Japan and the Middle East. Arab News’s launch was well received by Tokyo, with both Japan’s Defense Minister Taro Kono and Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike attending the launch event on October 21, 2019.

The Middle East is also increasingly attractive within Japan. In a survey of Arabic-language students in Japan, most cited their interest in Arabic culture as a motivating factor behind their decision to learn the language. Although Japan’s modern ties with the Middle East date back to the nineteenth century, contact with the Middle East had largely been minimal until the mid-twentieth century. One of the first major encounters between Japan and the region – the attempt of a Japanese company to export oil from Iran following the United Kingdom’s blockade of Iranian oil – was recently popularized in Japanese pop culture. The case of a Japanese firm busting an oil blockade against Iran was the subject of a novel by prominent right-wing writer Naoki Hyakuta and was adapted into the popular 2016 film Fueled: The Man They Called a Pirate, directed by Takashi Yamazaki. This film told the story of the Idemitsu incident (1953), in which a Japanese oil company imported oil directly from Iran following Iran’s nationalization of its oil industry. Japan’s importation of Iranian oil gained notoriety both in Iran and in Japan. When the Mainichi newspaper reported on Iranian President Rouhani’s visit to Tokyo in 2019, the Idemitsu incident was referenced as one of the key events that had solidified a strong Japanese-Iranian relationship despite Japan’s close alliance with the United States. It was not lost on anyone that the incident bore a striking resemblance to geopolitics and Japan’s foreign policy choices today.

Arabs think Japan would be 'the most neutral mediator for a peace deal between Israel and Palestine.'

Section Six

Conclusion

At present, Japan’s strongest relationships in the Middle East are with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Japan also enjoys warming relations with Israel and prioritizes maintaining good relations with Iran. Tokyo has also sought to diversify its regional trade relationship beyond oil. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have welcomed this push as it closely aligns with both countries’ strategic priorities to harness technology in their transitions to post-oil economies. Tokyo’s focus on diversification has also brought Japan’s business community into a closer relationship with Israel, where a significant amount of R&D takes place.

Despite Japan’s reluctance to deploy hard power, it has cultivated strong relationships with the Middle East by emphasizing its role as a neutral honest broker for the region. Japan’s Defense Minister and former Foreign Minister Taro Kono expressed a desire to leverage these relationships so that Japan can take on a larger political role in the region, such as acting as a regional conflict mediator. This would be consistent with Tokyo’s larger grand strategy to strengthen a rules-based global order to constrain a rising China in a world where U.S. power and influence are growing more uncertain.

Prime Minister Abe has calibrated Japan’s foreign policy in the Middle East to distinguish Japan from China as a trusted partner for the region. This is also consistent with how Japan has approached its partnership with the European Union. Today, Japan’s interests in the Middle East go beyond a narrow mercantilist emphasis on securing oil deals. Tokyo recognizes that the maintenance of Japan’s energy security requires Japan to play a larger political role in the region as a mediator. While Japan will likely never be able to draw upon hard power levers in its own diplomacy toward the region, its soft power and diplomatic influence have established it as a credible partner for many capitals in the Middle East.

Japan continues to recognize its alliance with the United States as the cornerstone of its national security strategy and views the rise of China’s and North Korea’s ballistic missile and nuclear programs as its most pressing challenge. As such, Tokyo will remain sensitive to Washington’s preferences in the Middle East. However, the challenge for Tokyo will be how to balance the needs of Washington while maintaining Japan’s own web of relationships in the region. This challenge is also an opportunity for Tokyo. Japan’s close relationships built up over decades in both Washington and Middle East capitals could be leveraged in the future to allow Japan to take on a greater role in the Middle East and the world.

Christopher Lamont is Associate Professor and Assistant Dean of International Relations at Tokyo International University. Previously he held a tenured position at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. In addition to his many scholarly publications, his writing has also appeared in Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, and the Washington Post's Monkey Cage.