'Summoning Memories: Art Beyond Chinese Traditions' Themes

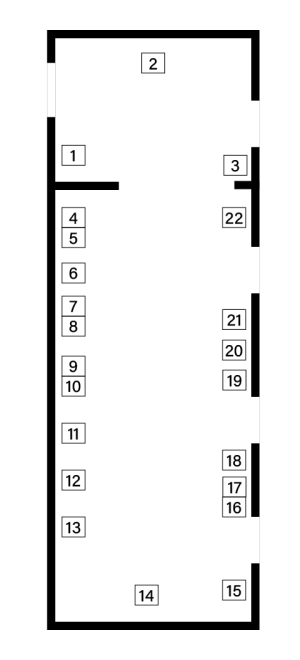

Jump to: Gallery 1 | Gallery 2 | Gallery 3 | Gallery 4 | Gallery 5 | Lunar New Year

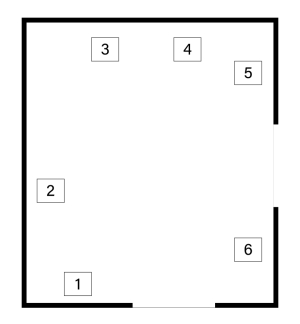

Gallery 1・Evoking the Past: People and Places

The artist Sun Xun has written that “history is a tool that can be manipulated by either the government, or an artist, to serve their own goals.” This can be extended to the political history of places like the Forbidden City or personal memories from the trajectory of one’s own life where past reality may be subverted to create new political or personal meaning. Artists continue to evoke memories of the past. In this gallery, Zheng Chongbin is engaging with and reinventing the six canons of the fifth-century art historian Xie He, which continue to be integral to connoisseurship today, and Liu Wei critiques the people and precedents of the art historical establishment. The endurance and continued resiliency of these conversations with tradition are at the heart of these art works and this exhibition.

- Liu Wei, Untitled No. 6 “Flower,” 2003, Accordion album of twenty-four leaves with silk brocade cover; pencil acrylic, ink, and watercolor on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Zheng Chongbin, New Six Canons (Xin Liufa), 2012, Set of six panels, ink and acrylic on Xuan paper. Collection of JYCO. LLC

- Sun Xun, The Time Vivarium-11, 2014, Acrylic and ink on paper mounted to aluminum, Pizzuti Collection

- Sun Xun, The Time Vivarium-16, 2014, Acrylic and ink on paper mounted to aluminum, Pizzuti Collection

- Zheng Lu, Water in Dripping – You, 2016, Stainless steel, Courtesy the artist and Sundaram Tagore Gallery

- Liu Wei, 180 Faces, Mixed media, Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly

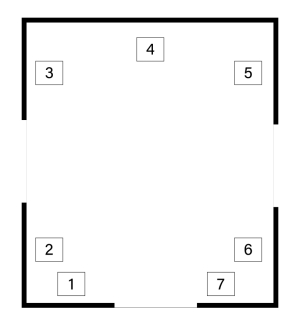

Gallery 2・Ink Alchemy: Beyond the Brush

Chinese ink landscape paintings have rarely been about depicting landscapes. Realistic depictions of craggy mountain ranges with jutted peaks or numinous landscapes shrouded with mist are always considered secondary to the “spirit resonance” or energy (qi) which animates the cosmos as expressed by the calligraphic imprint of the brush. The symbolic meaning of monochrome brushwork is traditionally analyzed as a metaphor for political, social, religious, and psychological themes, the ink stroke of the brush an indicator of the inner strength or personality of the individual. Landscapes are a spiritual environment, a space to find or lose ourselves, a visible context for our engagement with the invisible, the many layers of interpretation depending on the knowledge of the viewer and/or the intent of the artist.

The artists in this gallery, of different generations and different backgrounds, are in dialogue with the traditional use, meaning, and materials of ink painting. They move beyond the brush, using the photographic medium of cyanotype, or thousands of pinpricks to do “painting with needles.” Some use the physical materiality of ink to impress their body on canvas. These “ink paintings,” some without ink, evoke memories of Buddhist sanctuaries and spiritual enlightenment. They are reflections of personal journeys to relate the mind, energy, and spirit to the body, the cosmos, and the brushstroke.

- Irene Zhou, The Universe Lies Beneath, 1998, Mixed media on silk, Collection of Mee-Seen Loong and Jeffrey Hantover

- Ren Pan, Sleep Painting-12.31.14, 2014, Water, body heat, ink, and despair on canvas, Courtesy Ren Light Pan

- Fu Xiaotong, 719,560 Pinpricks, 2019, Handmade paper, Courtesy the artist and Chambers Fine Arts

- Bingyi, Can the Eyes Sing? The Bodies of the Sacred Mountains, 2021, Ink on paper, Courtesy the artist and INKstudio

- Zhang Jian-Jun, Rubbing Planet in Shui-mo Space, 2022, Chinese ink, oil paint, acrylic, rice paper on canvas, Courtesy the artist

- Lui Shou-kwan, Zen Painting, 1974, Chinese ink and color on Xuan paper, Collection of Alisan Fine Arts

- Wu Chi-Tsung, Wrinkled Texture 113, 2021, Cyanotype photography, Xuan paper mounted as a hanging scroll, Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly

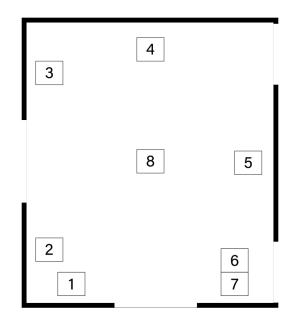

Gallery 3・Landscapes, Cityscapes: Lost and Haunted

The rapid pace of China’s modernization over the past decades has created ecological threats via the degradation of the environment as well as significant human costs: lives uprooted, homes and jobs lost, and the poor conditions of migrant workers. Artists respond to these environmental and personal traumas by reinventing and deconstructing landscapes and cityscapes. The Three Gorges project (Sanxia Gongcheng) spanning the Yangzi River created the largest hydroelectric river dam in human history, and was planned to supply one-ninth of China’s electric power, equivalent to 50 million tons of a coal a year, 25 million tons of crude oil, or 15 nuclear power plants. Many in China argue that the dam will control chronic flooding in southern China and lower greenhouse gas emissions. However, the human cost has been catastrophic, causing the forced migration of 1.3 million people and the flooding of 1,400 villages and towns, as well as the destruction of numerous historical and archaeological sites now permanently lost under the submerged landscape. New cities have emerged, almost mirage-like above the rising waters, permanently changing the topography of this region. The threat of environmental effects from the industrial pollution, created by the submerged buildings and factories, looms over the waters and air of these rural Chinese villages.

The artist Yun-fei Ji describes the traumatic decomposition of the landscape he witnessed during his visits to the region, which he then illustrated in his paintings: “I found that some villages were already gone, yet not completely razed roadside. People had to tear down their houses before they moved out. I kept walking toward the former residence of Qu Yuan and a large town near Wu Gorge as well as a town below White Emperor City. Basically, all of it was slated to be buried underwater… I’m interested in villagers and how they adapted when forced to move to the city. They lived on the margins… and were very creative in finding ways to survive. These are the people who are building modern China.”

- Wang Tiande, Playing with the Snow on the Boat, 2019, Ink, rubbing, and burn marks on Xuan paper, Collection of Diane H. Schafer

- Xu-Bing, Landscript, 2002-2003, Ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Zhang Dali, 100 Chinese (10 Heads), 2001, Synthetic resin, Courtesy the artist and Eli Klein Gallery

- Liu Xiaodong, Wolf Smoke, 2006, Painting, stretched, oil on canvas, Private Collection, New York

- Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration, 2008, Ink and watercolor on xuan paper mounted on silk, Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery

- Yang Yongliang, Phantom Landscape III, page 1, 2007, Media inkjet print on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Yang Yongliang, Phantom Landscape III, page 2, 2007, Media inkjet print on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Zhan Wang, Garden Rock #29, 2001, Sculpture, stainless steel, Private Collection, New York

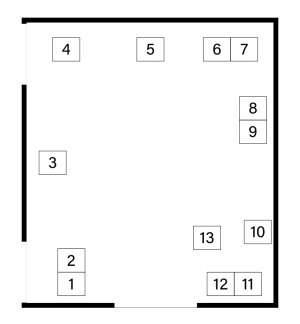

Gallery 4・Language and Scholarly Traditions: Remembered and Reinvented

Limestone rocks known as Scholar’s Rocks were idealized in Confucian court culture as points of meditation in lavish gardens or on the desks of scholar-officials practicing their calligraphy. Rocks were imbued with sacred powers, revered in Daoist philosophy as symbolic of utopian paradises where immortals gathered or centers of Buddhist sacred beliefs. Some artists regard these rocks as the “stem cells or the DNA” in the structure of Chinese ink landscape painting, capturing and embodying the spirit and life force (qi) within them. These rocks can be painted on paper with brush and ink, fabricated with stainless steel, digitally manipulated with pools of blood, or carefully woven from strings of newspaper to create personal memorials to departed loved ones. These rocks embody the collective memory of traditional Chinese culture as well as extremely personal responses to either a fractured society or individual tragedy.

The practice of calligraphy is intertwined with the spiritual and physical spaces created by Scholar’s Rocks. Instead of performing the art of calligraphy using the shared language of standardized Chinese, these artists are creating new conceptual languages and revitalizing dying languages. In both cases, the use of either newly created or rarely used characters addresses issues of inclusion and exclusion. Xu Bing’s Square Word Calligraphy comments on the difficulties of immigration and assimilating into a new culture. Tao Aimin uses Women’s Language (nü shu) to comment on gender and status; her goal to preserve and transmit the stories of the lives of women in rural Hunan province. This otherwise lost language instead is used to shape the cultural memories of these marginalized women. In both cases, the artists are using traditions of Chinese language and calligraphy to create new meanings for the characters and subvert their meanings.

- Hong Lei, Chinese Landscape: Liu Garden (Zhuozhengyuan Suzhou), 1998, Photograph, Private Collection, New York

- Hong Lei, Chinese Landscape: Liu Garden (Zhuozhengyuan Suzhou), 1998, Photograph, Private Collection, New York

- Liu Dan, Taihu Rock of the Liuyuan Garden, 2019, Ink on xuan paper, Collection of Henry and Vanessa Cornell

- Tao Aimin, In a Twinkle No. 6, 2011, Ink rubbing on paper, set of three hanging scrolls with nushu (women’s script), Courtesy the artist and INKstudio

- Xu-Bing, Introduction to Square Word Calligraphy (New English Calligraphy), 1994-1996, Calligraphy, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Xu-Bing, SWC-Sketch for Song of Wandering Aengus Poem by William Butler Yeats, 1999, Calligraphy, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Xu-Bing, SWC-Sketch for Song of Wandering Aengus Poem by William Butler Yeats, 1999, Calligraphy, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Xu-Bing, SWC, Song of Wandering Aengus by William Butler Yeats, 1999, Calligraphy, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Xu-Bing, SWC, Song of Wandering Aengus by William Butler Yeats, 1999, Calligraphy, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Kelly Wang, Microcosm 7, 2021, Newspaper on muslin, Courtesy the artist

- Kelly Wang, Microcosm 12, 2021, Newspaper on muslin, Courtesy the artist

- Kelly Wang, Microcosm 8, 2021, Newspaper on muslin, Courtesy the artist

- Kelly Wang, Entanglement, 2021, Newspaper, wire, muslin, acrylic, and wire, Courtesy the artist

Gallery 5・Word and Image

The art works in this gallery demonstrate different ways artists tell stories, creating conversations with ancient Chinese texts or instances where quite literally the text itself, that is the individual characters for “the past” are weighing down on “the present” (Gu Jin 古今). Some are personal stories, while others are ghost stories. Drawings in ink pen aspire to recreate the cosmos, while calligraphy with the ink brush reveals more personal journeys. Some representations are quite direct, pairing word and image, and reimagining ancient Chinese texts like the Classic of Mountain and Seas (Shanhaijing 山海经), dating to the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) as contemporary political and social commentaries. This interaction of visual imagery ± either with narrative texts or allusions to literary and philosophical traditions — creates moments for deep contemplation and close looking.

- Yang Yongliang, Imagined Landscape, Rabbit, 2022, Giclee print on fine art paper, Courtesy the artist

- Zhang Hongtu, Zodiac Figures, 2002, Earthenware with three-color (sancai) glaze, Courtesy Zhang Hongtu

- Hong Hao, Selected Scriptures: The Art of War, 1996, Print, silkscreen, Private Collection, New York

- Qiu Anxiong, New Classics of Mountains and Seas: Zi Ru Ga, 2018, Ink and color on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Qiu Anxiong, New Classics of Mountains and Seas: Ha Lei (Harley), 2018, Ink and color on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Wang Fangyu, The Past Weighing on the Present (Gu Jin), Ink on tinted paper mounted as a hanging scroll, Private Collection

- Qiu Anxiong, New Classic of Mountains and Seas I (Shanhaijing): Bitu (Bomber), 2008, Woodblock print, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Qiu Anxiong, New Classics of Mountains and Seas I (Shanhaijing): Xuanbei (Whirleybird Helicopter), 2008, Woodblock print, ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Bingyi, Fairy of Hairy Rocks, 2019-2020, Ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Bingyi, Fairy of Mountain and Rivers, 2019-2020, Ink on paper, Private Collection, New York

- Cui Fei, Manuscript of Nature V_PT., Installation, tendrils, and pins, Courtesy the artist and Chambers Fine Art

- Chu Chu, Whispers of Trees-Tea, 2011-17, Photography, calligraphy, Chinese ink on paper, Collection of Alisan Fine Arts

- Ren Pan, Untitled (crying is painting) – Irvine, CA 01.12.15, missing date, Water, ink, alcohol, teary eyes, and blurred vision on canvas

Courtesy Ren Light Pan - Fung Ming Chip, Post Marijuana, Ink on paper, mounted as a hanging scroll, Private Collection, New York

- Lin Guocheng, Prehistoric, 2016, Ink drawing, Private Collection, New York

- Hong Lei, Autumn in the Forbidden City (Dusk of the Forbidden (West Veranda of the Taibe Temple)), 1997, Photograph, Private Collection, New York

- Hong Lei, Autumn in the Forbidden City (Dusk of the Forbidden (East Veranda of the Taibe Temple)), 1997, Photograph, Private Collection, New York

- Peng Wei, The One in My Dreams – Wu Qiu Yue 2, 2020, Ink on flax paper, Courtesy the artist and Tina Keng Foundation

- Peng Wei, The One in My Dreams – Yan Ru Yu 1, 2020, Ink on flax paper, Courtesy the artist and Tina Keng Foundation

- Peng Wei, The One in My Dreams – Huan Niang 2, 2020, Ink on flax paper, Courtesy the artist and Tina Keng Foundation

- Peng Wei, The One in My Dreams – Tai Yuan Yiniang, 2020, Ink on flax paper, Courtesy the artist and Tina Keng Foundation

- Jennifer Wen Ma, In Furious Bloom III, 2016, Inkjet print on Canson edition etching paper, Collection of Sarah Hogate Bacon

Lunar New Year

Zhang Hongtu

Born China, 1943. Lives and works in New York.

Zodiac Figures, 2002, Earthenware with three-color (sancai) glaze, Courtesy of the artist

Zhang Hongtu has based these sculptures on the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac cycle which have their origin in ancient Chinese traditions. During the Tang dynasty (618-907), sets of these clay figures — human figures with animal heads (rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, ram, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig) painted with this specific three-color glaze known as sancai — were buried in elite tombs to provide good fortune and a successful afterlife to their occupants. Summoning the memory of this 1000-year-old tradition, Zhang created his Zodiac Figures combining these ancient ceramic techniques with the popular hands-behind-the-back pose and costume of popular ceramic figures of Communist leader Mao Zedong (1893-1976) collected in the 1950s and 1960s.

Zhang wrote: “There are three elements in this work: The Tang tri-colored pottery texture, the Mao outfit, and the posture of the twelve zodiac animals… When I mixed these three seemingly unrelated elements, I intended to create new images that have connections with reality — connections which transcend the meaning of the twelve animals. This strange mixture parallels the current situation in China: a mixture of old and new, East and West.”

Asian American artist Zhang Hongtu, a leader of the “Political Pop” movement in contemporary Chinese art lives in Queens, New York, after emigrating from China in the 1980s. By creatively juxtaposing ancient China rituals with the Communist leader, he whimsically critiques systems of power.

Click here to complete the exhibition proposal form.

Click here to complete the program proposal form.