When Arts and Policy Intersect: The Story Behind 'Buddhist Art of Myanmar'

Asia Society Museum’s history-making exhibition, Buddhist Art of Myanmar, opens February 10, 2015, in New York. Exploring Buddhist narratives and regional styles, Buddhist Art of Myanmar is the first exhibition in the West to focus on art from collections in Myanmar. Learn more

The galleries of Asia Society Museum in New York have been a beehive of activity this past week, filled with the sounds of hammers and drills, and the smells of sawdust and fresh paint, as workers readied the space for the grand unveiling of Buddhist Art of Myanmar, the highly anticipated exhibition opening February 10.

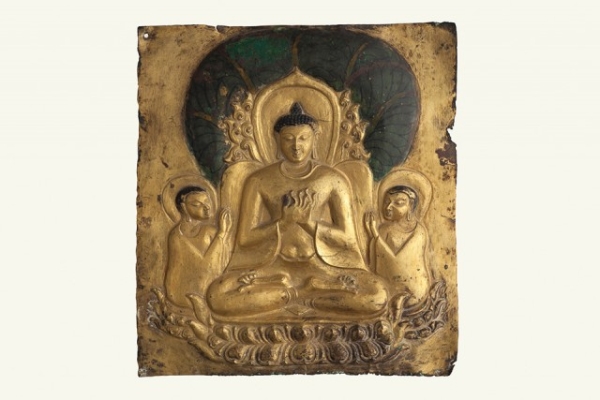

Buddhist Art of Myanmar features a collection of sculptures, textiles, and paintings from the Southeast Asian nation also known as Burma — some objects dating back more than 1,600 years. “[Many of these objects] have never left Myanmar,” said Catherine Raymond, director of the Center for Burma Studies at Northern Illinois University. “So for me to see them in this sort of exhibition is extraordinary.”

Just as extraordinary as the pieces themselves is the story of how this history-making exhibition came to be. Just a few years ago, the idea of such a display on U.S. soil seemed impossible, and in fact, few would have imagined it could even happen today. But as Myanmar began to emerge from international isolation, Asia Society’s unique multidisciplinary structure put the institution in an uncommon position. While its policy arm helped facilitate political engagement between long-divided sides, the wheels were put in motion for Asia Society to be part of the country’s artistic reemergence on the world stage, as well.

This spring, Asia Society New York presents Myanmar's Moment, a season of programming on Myanmar, including two shows by one of Myanmar's most revered traditional performing arts troupes, Shwe Man Thabin. On April 10 and 11, Shwe Man Thabin will perform a Zat Pwe, a form of Myanmar entertainment combining dance, music, and theatricality traditionally performed at pagoda festivals. Learn more

“Often arts and culture open the door to other dialogues that take place in the policy arena,” said Peggy Loar, Asia Society interim vice-president of global arts and culture and museum director. “In this case it was the reverse, and that’s why Asia Society is so interesting with its diverse pillars of education, policy, and arts and culture.”

In 2008, political winds began to shift in Myanmar. The country’s constitution was amended, and after decades of isolation and repressive policies, the military government explored the early stages of reform. Cautiously optimistic about these changes, the following year U.S. President Barack Obama embarked on a course of “pragmatic engagement” between the United States and Myanmar. It was then that the Asia Society launched its Myanmar Initiative to help strengthen bilateral relations between the two countries.

Over the following two years, it became obvious that something significant was happening in Myanmar. In 2010, elections were held for the first time in two decades and pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest, where she had spent the better part of 20 years. Then in early 2011, the military government ostensibly began transitioning to a civilian-run run body and new President Thein Sein, himself a former military commander, was sworn in.

In 2011, Asia Society convened the first meeting for officials from Myanmar to engage with government representatives from across the West, ASEAN, and East Asia on the country’s somewhat opaque and poorly understood transition. During this period, Asia Society was also one of several organizations that facilitated unofficial meetings that allowed countries to engage in discussions in an informal setting to improve communication, address miscues, and strengthen understanding.

During a 2012 trip to Myanmar, Asia Society was able to meet with a number of officials to discuss the changing country and the U.S.-Myanmar relationship. At one such meeting, the topic of another U.S.-Myanmar cultural exchange was broached (in 2003, Asia Society brought a dozen of Myanmar's most celebrated performers to New York, exposing many in the audience to traditional Myanmar music and dance for the first time). “We met with the deputy minister of culture,” recalled Debra Eisenman, executive director of the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI). “We offered Asia Society’s museum as a welcoming host of artwork from Myanmar to showcase some of the cultural history, arts, and artifacts that have rarely been seen in the U.S. before.”

It seemed a vague and distant hope at the time, but like Myanmar’s reforms, it materialized much faster than anyone anticipated. In September 2012, Aung San Suu Kyi and President Thein Sein made coinciding trips to the United States and each spoke at Asia Society events one week apart. There, they gave each other gentle praise in their respective efforts toward Myanmar’s democratic reform. The message was subtle but clear: relations between Myanmar’s military-backed leadership and Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratic opposition were thawing, as were relations between Myanmar and the United States.

“Thein Sein’s speech [at Asia Society in New York] was broadcast in Myanmar, which was surprising in its openness,” Eisenman said. “It helped broadcast the pretty liberal message of wanting to create the space for democracy and transparency in his country.”

During Thein Sein’s visit to Asia Society, the idea of an art exhibition to introduce Americans to Myanmar was brought up again. Recognizing the need for cultural as well as political diplomacy, he gave his blessing.

With the wheels now officially turning, Asia Society museum representatives flew to Myanmar to begin talks with the Ministry of Culture. But it was a far from smooth process. “Myanmar’s experience with the West in the past had left them apprehensive,” said Adriana Proser, John H. Foster senior curator for traditional Asian art at Asia Society Museum. “A lot of works from Myanmar ended up in England during the colonial period (1885-1948) and never came back.”

Initially, the Myanmar side wanted to send several replica items rather than the original artifacts. “We had to go back and say that it’s really important that we use the original objects if Myanmar wants to impress the American people with its culture,” Proser recalled. “There was a certain amount of wariness and need for reassurance that these were loan objects that would be sent back after the exhibition.”

After a long series of discussions with officials, museums and curators in Myanmar, an exhibition with more than 70 authentic artifacts was finalized (part of the process was detailed in a 2013 New York Times story). “What we needed from the beginning was the trust,” Myanmar's Minister of Culture Aye Myint Kyu told Asia Society in January. “Of course we knew it was an important opportunity for our country to be able to share these works. But we needed to be sure they would be cared for.”

Objects for the exhibition include Buddha statues dating back to the fifth century CE. When it came time for these items to leave their homeland, it was an emotional experience for their caretakers in Myanmar. At one museum in the central part of the country, staffers shed tears as one of their Buddha statues departed for New York.

In late January, the sacred sculptures began arriving to Asia Society in New York. “The exhibition really brings everything together,” ASPI’s Eisenman said. “And it’s what makes Asia Society such an interesting organization. We can focus on policy, but because we are balanced by two pillars — arts and culture and education — we become accessible to everybody and can really build a comprehensive discussion on places and issues.”