Briefing MONTHLY #16 | Special Focus: Indian Elections

It’s a big year of voting across Asia but India is like nothing else. Greg Earl recounts a week in the middle of the world’s biggest election campaign.

Showstopper … India has 375 cable channels and this month there’s only one show in town

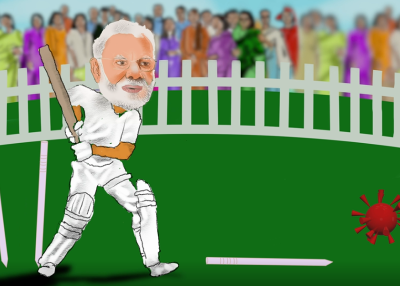

NO GANDHI v MODI

Thursday 4pm: Seeking refuge in a café from the 40º plus heat, I discover news channels have now been reporting live for four hours since I arrived in New Delhi on Prime Minister Narendra Modi visiting his seat in the Hindu heartland city of Varanasi. And he hasn’t even appeared yet! Commentators furiously debate the news that the latest member of the Nehru-Gandhi family to enter politics - 47-year-old Priyanka Gandhi Vadra - has just pulled out of a touted head-to-head battle with Modi. The headlines tell the story: “Show of strength spooks Gandhis,” “Varanasi chants: NaMo, NaMo,” and “Cong (for the Gandhi’s Indian National Congress Party) to chicken out.” The saffron-soaked Modi eventually does a highly stage managed six km, three hour “mega roadshow” through a crowd estimated at 750,000. And the equally “mega” TV circus doesn’t stop into the night until it’s too late to watch any more.

PRESIDENTS OR PARLIAMENTS

Finding NaMo … the BJP’s marketing bandwagon at its head office in New Delhi

Friday 11am: Check in with Jay Shah, who runs Friends of BJP in Australia. He is now back in his home town of Ahmedabad in Gudjarat state to vote and campaign. In 2014 the BJP won a clean sweep of all 26 seats in Gudjarat (where Modi made his name as chief minister) and so I ask what’s the point of coming all the way back to vote? Jay says expat visitors help lift the spirits of the local campaign workers. But even better, he has hit the big time having spent a day campaigning with Modi’s chief numbers man Amit Shah. “I’m very glad I made the trip back,” he says wistfully.

2pm: Indian elections are conducted a bit like military campaigns with seven phases this year backed up by the deployment of central government paramilitary forces across the country. But for former Election Commission of India chief O.P. Rawat, the real secret weapon is the EVM, as the country’s indigenous electronic voting machines are universally known. India is marketing these machines to other developing country democracies because their battery power makes them resilient where electricity is unreliable and their operation independent of the internet makes them less vulnerable to hacking compared with other computerised voting. But when all two million are downloaded on May 23, they produce a swift result. Rawat says the overseas marketing of a new model tested in this election will restart later in the year.

5pm: When India’s final round of voting closes on May 19, Yashwant Deshmukh may be one of the more watched people in the country. As chief editor of CVoter, his analysis of exit polls conducted through the rounds of voting (but by law not disclosed) will fill the void until the results are announced four days later. He says picking the likely national vote share is relatively easy. But the country’s mix of ethnic, caste and religious differences make picking the seat shares in the first past the post system “as abstract as it can get.” He believes presidential systems better suits the Asian culture of respecting leaders but India has an intensely parliamentary system with many parties. The big thing to watch is whether Indians are adopting more of a presidential leadership mindset which would benefit a person like Modi.

TAKING THE UP ROAD

Countdown … an Indian Congress Party street rally in Kampur, Uttar Pradesh

Saturday 6am: Indians say all election victories start in Uttar Pradesh (UP), which is the world’s most populous sub-national government with 200 million people. There’s no better way to discover why it’s so important than take the new fast train Modi launched in February from New Delhi to Varanasi. We stop in Kanpur which was once known as the Manchester of the East for its leather industry, but is now an election hotspot in the fourth round of voting in two days. It’s a classic Indian three-cornered contest between the dominant BJP, the once dominant Indian National Congress and a sudden worrying (for the big two) alliance between two caste-based regional parties which have put historic rivalry aide and are running as the Mahagathbandham (or Grand Alliance) this time.

3pm: We’ve now crossed the Ganges River twice outside Kampur in a quest to find Priyanka Gandhi headlining a rally to regain the Congress momentum in UP after all the hoopla three days earlier for Modi’s roadshow. The BJP won 71 out of 80 seats here in 2014 wiping out the Gandhi family-led Congress, so it can probably only lose ground this election. But the Congress is split over deal making with small rivals like the Grand Alliance, so the anti-BJP forces may be fractured. (The Alliance staged a noisy, attention seeking, fast motor bike rally through the city streets earlier.) But unfortunately, the Priyanka rally is over before it even starts due to skirmishing between BJP and Congress supporters. The latest Gandhi scion – who reminds people of her grandmother and former prime minister Indira - is off to another city. We stumble upon a small Congress rally in a local neighbourhood but it’s only a few minutes before the one-day curfew on rallies ahead of the fourth round of voting. The speaker has worked himself into a last-minute frenzy over how Modi has besmirched the achievements of the great Congress heroes like Jawahalal Nehru (Priyanka’s great grandfather) who built the country.

Dinner time … Police director general OP Singh (center) takes a campaign break in Kampur.

10.30pm: As the heat cools from the day and the campaign, UP state police chief O.P. Singh tells a group of foreign visitors how challenging it is to keep the electoral peace in the world’s most populous police command. “Elections are fought very passionately in India. Lucky this year we have had almost no incident,” says one very relieved sounding policeman. But he seems a little downcast that the voter turnout might be down in his patch despite the good work. Still there’s time for dinner - which has been conveniently prepared by a catering business run by the local BJP candidate’s daughter.

REVERSE DOOR KNOCKING

Sunday 11.30am: Rallies are now banned ahead of the next day’s voting, although local personal vote canvassing door-to-door is still OK. But this is the world’s most populous state. We’re told the BJP’s man Satyadev Pachauri, a state government minister seeking a national seat, is out canvassing. But in a small courtyard it seems the whole street has come to him and there are several dozen men pushing in to hear their extremely tired-looking candidate’s final words. The last thing he wants to see are some eager political observers from abroad.

1pm: The candidate from the Grand Alliance’s Samajwadi Party, which represents the Yadav (or peasant) caste, can’t be found, which is not surprising after weeks of political guerrilla warfare against the BJP’s 2014 election stranglehold here. Many observers say breaking the BJP seats tally here in UP will be one of the most critical determinants of whether the now dominant party will be forced into a coalition government.

2pm: More first-time young voters were added to the electoral rolls in the average Indian seat this year than the total enrolment of Australian electorates. It is the not first time around for Paavin Gupta and Aishwarya Omar, who each work for the Indian arms of US multinational brands and are catching up at an up-market Kampur fusion restaurant Gin and Ginger, when we talk. They are the sort of aspirational young Indians who fuelled the Modi wave in 2014 … and it seems they haven’t lost the love. Paavin is more inspired by Modi’s efforts to remake the traditional Indian welfare state. But Aishwarya, perhaps more surprisingly for a young woman, likes his recent tougher approach to national security, especially Pakistan.

9pm: The bar is dry due to one of the many election rules. But the conversation with local reporters is not. One finally puts some numbers down. The early signs of a poor turnout in the state in the first three rounds of voting suggests it has hit peak BJP (The party won state government in 2017 on the coattails of Modi’s 2014 success). This reporter tips only about 40 (compared with 71 in 2014) out of 80 seats for the governing party due to the disciplined campaign being run by the Grand Alliance of Dalit and Yadav parties. That starts to seriously threaten the BJP’s majority back in Delhi.

PRESSING THE BUTTON

Party time … voters at the Gur Narain Khattri College in Kampur

Monday 10am: Stepping into an Indian polling precinct is bit like the old Licence Raj meeting Bollywood. The rule book is daunting with the local magistrate having to implement 145 steps to a fair vote. But the atmosphere outside is more party time than party politics. There’s table soccer for the kids and a selfie station for recording the day for everyone else. The wheelchairs at the front gate and separate sitting area for women reflect this year’s participation priorities – women and the disabled. But my hope to give the much vaunted electronic voting machine a workout is quickly frustrated. My India Foundation hosts say this is the first such visit to a polling room by a group of foreign non-government observers. However, the room manager says no one gets to even see the machine (which is behind a screen on a desk) but the voters. The selfie station beckons.

IF THESE WALLS COULD TALK

The newly built BJP head office (left) and the Congress Party’s longstanding New Delhi building

Tuesday: Visiting the New Delhi headquarters of India’s two biggest political parties is a journey into the soul of competing visions for the world’s biggest democracy.

9.30am: The BJP has doubled its membership to 110 million under Modi’s leadership to overtake the Chinese Communist Party as the world’s biggest political party. And foreign affairs chief Vijay Chauthaiwale, a former corporate who ran the successful 2014 campaign, says the new corporate styled office reflects the party’s drive to create a modern, high tech political machine that stretches every corner of the country. “We believe in the science of organisation, not the will of a dynast to get to the top because there is no one else,” he says without actually naming the Gandhi-led Congress. He says the biggest change in Indian politics is that Modi has made political leadership respected rather than a job to be scorned for corruption and inefficiency.

11am: Former political journalist (and co-author of a 2014 report on Australia-India relations), Ashok Malik, is now taking the long view from a job with the country’s president. He says a doubling of the economy over the next decade; urbanisation creating three massive conurbations around Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore-Chennai; and a communications revolution (250 million Facebook users and 250 million WhatsApp users) will change Indian politics. “Technology is helping unite Indians across geography about how they think about everything from festivals to terrorism. This is changing the way we look at local and national elections.”

12.15pm: I get the lowdown from CNN-News 18 political editor Marya Shakil … and she’s talking like she’s still broadcasting to 1.3 billion people. “People voting for him (Modi) are voting for the man and people not voting for him are voting for the party.” “This is not a wave election but there is an undercurrent for Narendra Modi.” “It’s interesting to observe the shifts from one state to another. More than jobs, national security is now an issue.”

2pm: Congress communications chief Randeep Surjiwala contrasts his more humble accommodation in an old government building compared with the BJP without being asked, suggesting the government is more concerned with fancy offices than helping the poor. He hands over a list of 125 broken BJP promises from 2014 to explain why the government has abandoned social and economic reform debate this time around in favour of simply fanning fears about national security. He says the BJP has used “isolation, division and diversion as tools of state” to undermine the ability of India’s non-Hindu nationalist religious and social groups to “walk alongside” the majority. “It’s not about right or left or center. It’s about preserving India’s civilisational values. That’s the broad difference of idealogy at this election,” Surjiwala says. And he firmly rejects suggestions the country’s oldest and once dominant party is struggling to find its way as one of many opposition parties: “Our ideology is based on collaboration.”

Congress media spokeswoman Shama Mohamed and communications chief Randeep Surjiwala

STATE RULES, OK

Wednesday 11 am: One of the many overwhelming things about Indian elections is the vast amount of media coverage and books there are to wade through. A morning before meetings is never enough! One of the more readable ones this year is Democracy On The Road by journalist turned Morgan Stanley banker Ruchir Sharma about hitting the election trail during various state and national voting for 25 years. It has been my road map for the week, especially useful because his travelling team made repeat visits to UP over the years. He concludes: “The 2019 election is being cast as a nationwide showdown between Modi and the rest, a referendum on India’s appetite for strongman rule and commitment to democracy. Most likely, the election will shape up as a series of state contests.” So, Modi could still win a third of the popular vote as he did in 2014 particularly in the northern Hindu heartland. But “the outcome will depend on whether opposition parties, work together to unseat him.”

Wait, there’s more … a travel guide for political junkies

Greg Earl visited India with an international election observer group sponsored by the India Foundation, with assistance from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

ABOUT BRIEFING MONTHLY

Briefing MONTHLY is a public update with news and original analysis on Asia and Australia-Asia relations. As Australia debates its future in Asia, and the Australian media footprint in Asia continues to shrink, it is an opportune time to offer Australians at the forefront of Australia’s engagement with Asia a professionally edited, succinct and authoritative curation of the most relevant content on Asia and Australia-Asia relations. Focused on business, geopolitics, education and culture, Briefing MONTHLY is distinctly Australian and internationalist, highlighting trends, deals, visits, stories and events in our region that matter.

Partner with us to help Briefing MONTHLY grow. Exclusive partnership opportunities are available. For more information please contact [email protected]

Read previous issues and subscribe >>