Briefing MONTHLY #28 | June 2020

India’s double trouble | China business | Singapore votes

Animation by Rocco Fazzari.

STUCK BETWEEN COVID AND CHINA

It is just a year since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi won a sweeping election victory making him the country’s most powerful leader for more than a generation and opening the way to potential big initiatives in diplomacy and economic reform. Now he heads a country which is facing its first economic contraction in 40 years, counting the cost of an ill-planned severe pandemic lockdown and recoiling from the worst military clash with China in 60 years.

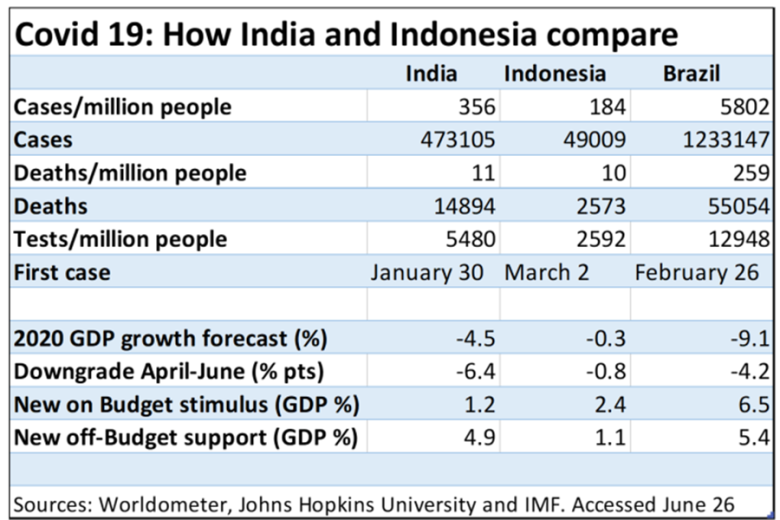

India’s initial approach to COVID-19 was a stark contrast to its fellow populous, multi-ethnic Asian democracy Indonesia. Modi used his political strength to impose a sudden nationwide Chinese-styled lockdown when Indonesia’s less politically strong President Joko Widodo vacillated saying Indonesians would not accept such a measure. But what looked like a tough, forward-looking Indian strategy then, now looks badly handled, with unemployed workers spreading the virus as they returned home and the economy suffering a sharp slump. On the other hand, Indonesia’s economy remained more open amid a more voluntary lockdown. As democracies with substantial but variable quality second tier governments, both countries have also seen big variations in infections and policy responses at the local level. With infections still rising in both, and questions about whether Indonesia’s data collection is less reliable than India’s, it is still hard to assess the outcome of the different lockdown strategies. But India’s economic outlook has been downgraded much more sharply than Indonesia’s over the past three months, reflecting its apparent poorer pandemic management.

Despite the focus on Asian pandemic success stories in Taiwan and South Korea, the lessons from these more heterogenous large countries may well be just as important. But, as the chart below shows, both are doing better than their peer country Brazil.

- Epidemiologist Raina MacIntyre explores the different Indian and Indonesian pandemic strategies in this East Asia Forum piece.

- This India Today article examines how the frontline states like Maharashtra and Gudjarat are preparing for the expected surge in COVID-19 by mid-July in the world’s second most populous country.

- With Indonesia’s pandemic statistics facing questions, this The Jakarta Post oped explains why the country needs more accurate local health data instead of centralised estimations.

Narendra Modi has taken part in 18 summits of various sorts with Chinese President Xi Jinping in the past six years underlining how he has spent considerable political capital maintaining relations with China. Meanwhile Chinese investment into India over the past five years is estimated to have grown from negligible to at least US$26 billion, which is a similar flow to what Australia has received. So, the vicious hand-to-hand fighting between Indian and Chinese soldiers on June 15 on their northern border hasn’t just broken a 60-year stand-off since the two countries fought a border war that China won in 1962.

It has also undermined a flow of capital and technology that was underpinning Modi’s Make in India manufacturing development strategy. And it has hurt the Chinese companies who were focussing on India as their new consumer growth market and a way to avoid US trade restrictions by making it an offshore manufacturing base. After adopting tougher scrutiny of Chinese foreign investors early in the pandemic (like Australia), Indian agencies are now stepping up economic sanctions by imposing a Chinese-styled informal customs clearance slowdown in response to the border clash. India’s overall two-way trade dependence on China is only half Australia’s but it has a large trade deficit which the recent Chinese investment was supposed to reduce by making more products in India. With both sides making it clear they want to avoid a more serious military conflict on the border, China appears to be gambling that India is more economically vulnerable to pressure due to its COVID-19 economic contraction.

- India’s economy was in trouble before the pandemic, argues Mihir Sharma in The Print.

- The recent more intense economic relationship between India and China should provide a basis for restraint, argues Vikran Khanna in The Straits Times.

- But Gideon Rachman, in The Financial Times, says China has finally driven India into America’s arms despite Modi’s efforts to remain more independent.

And, in ASIAN NATION below:

NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH

ASEAN'S NEW CHINA LINE

Southeast Asian leaders appear to have toughened their stand towards China in the South China Sea at their June Summit by more strongly embracing the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for dealing with disputes.

But while warning of unprecedented changes posed by COVID-19, they have not pushed forward quickly at the June 26 online meeting with any major new measures to enhance regional cooperation over the pandemic.

The Summit Chairman’s Statement, issued by host nation Vietnam, has added new language to the way ASEAN describes the South China Sea dispute which appears to reject Chinese historic claims to the territory by firmly embracing the UNCLOS principles. The Statement also uses firmer language to describe how the meeting discussed the maritime territory tensions suggesting there was greater concern about recent “serious incidents.”

It is not surprising that a Summit hosted by Vietnam, which has taken a more up-front role in resisting Chinese territorial claims, would use the opportunity to user tougher language. But it follows recent heightened concern about the issue from some other members, including Indonesia and Malaysia.

The statement welcomes collaboration with partners including Australia on the pandemic over information sharing, risk assessment and emergency responses. Vietnam's Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc warned in his opening address that: “The pandemic is fanning the flames of dormant challenges within the political, economic and social environment of the world and in each region.” The leaders announced a COVID-19 Response Fund without details of the funding and where it would come from. Some leaders talked up travel corridors within the region to speed recovery without any clear agreements. A regional stockpile of medical supplies has also been proposed and the group will undertake a study to be financed by Japan on the possibility of establishing an ASEAN center on public health emergencies, one diplomat was quoted as saying.

OLD FIGHTS, NEW LOSSES

Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad has already distinguished himself as the country’s longest serving and shortest serving leader. But he now seems determined to really be remembered as the most reluctant to leave office, after new manoeuvring to remain at the centre of power amid speculation the new government will call an early election. The nonagenarian seemed on the cusp of redemption in recent weeks after his Pakatan Harapan government lost power in February because the replacement Perikatan Nasional government can scarcely muster a majority in parliament. But now after yet again being unable to reach an agreement with his long-time rival and recent coalition partner Anwar Ibrahim about who would lead any return to power, he has nominated the chief minister of Sabah state Shafie Apdal as his preferred future prime minister. The new falling out with Anwar only seems to make it more likely that incumbent Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin will call an early election for August which would allow him to yet again avoid a test of his parliamentary numbers when the parliament is due to reconvene on July 13.

ISLAND HOPPING

China appears to have secured more influence in the South Pacific with Kirabati’s President Taneti Maamau re-elected to a second term after an election campaign partly focussed on his earlier decision to switch the country’s diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China. He wants to speed up infrastructure development to boost tourism which may fuel the struggle Australia has been involved in trying to prevent China gaining control of more regional infrastructure.

ASIAN NATION

MOOD SHIFTS ON ASIA

Source: Lowy Institute

Federal government efforts to broaden connections across the region in response to rising tensions with China have received some public support in the latest Lowy Institute foreign policy opinion poll, although there are still pitfalls.

The mood has shifted sharply against China for the second year in a row, underlining how the previously positive public opinion is now aligning more with the security establishment. Trust in China is at the lowest level recorded, at 23 per cent compared with figures around 60 per cent ten years ago. Indonesia is trusted by 36 percent, India by 45 per cent and Japan by 82 per cent – although those figures are all down on recent years, but not as much as China. Eighty-eight per cent of respondents support the Quadrilateral idea of a partnership of regional democracies. But two thirds of people say Australia should prioritise Australian interests over global agreements. And foreign policy based on economic interests rather than democratic values is favoured more than in the past.

Along with falling trust in India when the government is trying to build close bilateral ties, respondents are also more sceptical of the value of a free trade agreement with India, compared with Britain or the European Union. On the other hand, the mood is more positive towards Indonesia, with more people accepting it is a democracy than ever before in this polling series and a slight increase in confidence in President Joko Widodo.

CALLING 'TEAM AUSTRALIA'

The Business Council of Australia and Asia Society Australia Asia Business Taskforce will release its interim report on deepening economic links with Asia later this week. The report will urge Australian businesses to re-activate their Asian strategies, arguing that the region offers the most assured pathway of recovering Australia’s economic fortunes, particularly after the pandemic. It will also call on the Australian government and business to reimagine the 'Team Australia' approach to economic engagement with Asia, by combining resources, sharing leadership and focussing on execution of well-defined commercial outcomes in the region.

BEYOND CRICKET, CURRY AND COMMONWEALTH

The deferral of the Australia-India leadership summit in January due to Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s bushfire problems may well have turned out to be fortunate. When Morrison and Prime Minister Narendra Modi finally did the meeting online in early June they had much more to talk about and more urgently from the COVID-19 pandemic to the rising tensions with China on the Indian border. The Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) the two leaders agreed upon has finally taken Australia into a much deeper security relationship with India after many years concentrating on, but failing to reach, a trade agreement either bilaterally or through the Regional Comprehensive Partnership. An agreement to share military logistics will bring the two countries’ armed forces closer together for both exercises and regional disasters. But other new cooperation covers cyber threats, critical minerals, common standards on new technologies, and maritime cooperation.

However, the path forward on economic engagement remains to be charted with the two leaders agreeing to “re-engage” on a bilateral trade deal “where a mutually agreed way forward can be found.” But the series of sectoral economic cooperation initiatives in the new CSP suggests this approach might remain more significant than a trade deal.

- Rory Medcalf says in this Australian Financial Review piece that Australia’s long wait for a meaningful relationship with India finally seems to be paying off.

DEALS AND DOLLARS

CHINA BUSINESS: BACK TO TRADE

After ten years of rising Chinese investment in Australia, the commercial relationship has decisively gone back to the future with trade now again the main focus. The latest KPMG/University of Sydney survey shows Chinese capital inflow fell more in 2019 than it did into other major western destinations countries for the first time since Chinese outbound investment started slowing. The amount fell 62 per cent from $8.2 billion to $3.4 billion, which was the lowest amount since 2007 and compares with annual figures above $10 billion in many recent years. “The decline in new Chinese investment was in striking contrast to the significant growth in bilateral trade which reached its highest annual volume ever in 2018-19 with $235 billion, a 21 per cent increase,” the survey says. While the overall amount fell substantially, the survey underlines a continued shift towards smaller investments by private investors in new sectors away from the once dominant state-owned enterprise investment in the resources sector. And virtually half the inflow was due to the $1.5 billion takeover of dairy company Bellamy’s Australia by China Mengniu Dairy Company. Overall, there were only 42 transactions compared with 74 the previous year.

CHINA BUSINESS: DIVERSIFICATION RISKS

The Chinese trade restraints on Australian barley and beef exports reflect a complex mix of domestic factors in China, including its own focus on diversified food supplies, according to a new study. It suggests that Australian agriculture exporters need to respond with a better knowledge of the Chinese domestic imperatives and better links to alternative agriculture export markets. The study by Queensland University’s Scott Waldron says Australian producers should prepare for more of these interventions by China but are better placed to diversify than some other Australian exporters. It says: “There are strong indications are that such cases will continue and escalate. This is a function of deep-rooted forces and shocks generated by the political economy and politicised trade policy of Chinese agriculture, in an era of challenges to international rules-based trade in agriculture, including by China. Government and industry agencies require a more cohesive and rigorous approach to these risks.” The report says Australia should take the barley case to the World Trade Organisation, invest more in China market intelligence and alternate markets and that Australian farmers develop a better system for assessing the real cost of Chinese risks.

CHINA BUSINESS: INVESTMENT RULES

If there was one implicit deal at the heart of the 2015 China Australia Free Trade Agreement (CHAFTA), it was the way Australian exports got favourable export access to China in return for Chinese private investors getting the same access to Australia as investors from other major countries such as the US. This implicit deal – celebrated by the current Federal government at the time – was once mooted for extension to selected Chinese state-owned enterprises if they could prove themselves to operate like private companies. But all that has now been reversed by the government’s new foreign investment approval regime which creates a national security test for all investment in “sensitive national security businesses” regardless of the value of the investment. Then Prime Minister Tony Abbott underlined this new investment bond when he told Federal Parliament during President Jinping’s visit in 2014 that: “We trade with people when we need them; but we invest with people when we trust them.” As noted in the investment survey item above, Australian exports to China have risen strongly since then but inbound Chinese investment has fallen due to tougher Australian regulatory decisions and Chinese capital controls. The government says the new national security rules are not directly aimed at China but the future of the FTA CHAFTA agreement may be caught up in how they are applied.

ASEAN RISING

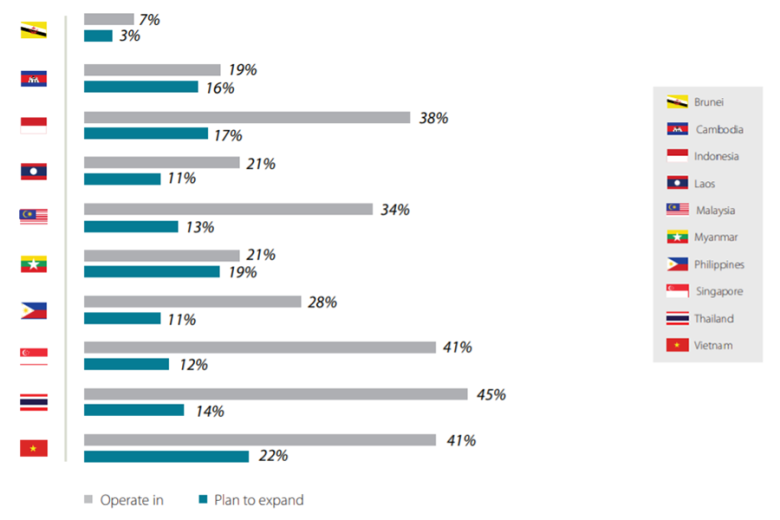

Australian business operation and expansion plans in Southeast Asia. Source: AustCham ASEAN survey 2020

Australian businesses in Southeast Asia are showing continued confidence in regional economic integration despite the scepticism amongst some analysts about the progress towards a regionwide commercial zone. A new survey of Australian-connected businesses operating in the region found 47 per cent think that integration of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is good for business while only 27 per cent say it is not important. This rising confidence figure has been a trend since the AustCham ASEAN survey was first done in 2017. It has occurred even though most Australian businesses in this region tend to have a country focus rather than a pan-regional operation. Surveyed before COVID-19 really hit, 19 per cent of the respondents said they had expanded their operations significantly in the past two years, and 85 per cent said they expected to expand over the next five years. But a short follow-up survey in April revealed 48 per cent thought the pandemic would be strongly negative and 38 per cent thought it would be somewhat negative, although this did not specifically refer to the investment outlook. The survey has further buttressed Australia’s increasing engagement with Vietnam, which is now seen as the most favourable place to expand, overtaking the Philippines and Myanmar in recent years and longer established economic partners such as Malaysia and Singapore. Meanwhile although corruption continues to be the biggest challenge for Australian business in the ASEAN region, the survey shows some interesting maturing of the economic outlook with lack of access to skilled labour overtaking barriers to ownership and investment as the next biggest challenge.

QANTAS FLIES OUT

Qantas has confirmed it will exit its minority stake in the Vietnamese airline Jetstar Pacific and is set to hand full control of the budget carrier over to co-owner Vietnam Airlines. Jetstar chief executive Gareth Evans says the group plans to sell its 30 per cent stake in Jetstar Pacific in future months pending regulatory approvals so it can focus on its other airlines. Jetstar Pacific was established in 2007 as part of a Qantas strategy to widen its presence in Asia through a series of partnerships using the Jetstar brand.

DIPLOMATICALLY SPEAKING

“We should avoid any reflex towards a negative globalism that coercively seeks to impose a mandate from an often ill-defined borderless global community. And worse still, an unaccountable internationalist bureaucracy."

Prime Minister Scott Morrison, October 4, 2019

"Australia’s interests are not served by stepping away and leaving others to shape global order for us. Isolationism would also cut us off from the world on which we are so dependent for our own security and prosperity."

Foreign Minister Marise Payne, June 16, 2020

DATAWATCH

COUNTING THE COVID COST

This chart shows the change in the Asian Development Bank economic growth forecasts between its April Asian Development outlook and its June revision. Overall, the entire developing Asia region is forecast to grow 0.1% this year compared with 2.2% in April. It is forecast to rebound to 6.2% average growth in 2021. (Japan and Australia figures come from the International Monetary Fund June World Economic Outlook update.)

WHAT WE'RE READING

What should Australia do to manage risk in its relationship with the PRC? by Peter Varghese (China Matters)

How Good is the Australia-China Relationship? by Allan Behm (The Australia Institute)

Mitigating the New Cold War: Managing US-China trade, tech and geopolitical conflict by Alan Dupont (Centre for Independent Studies)

In a debate increasing prone to sudden twists and harsh rhetoric, these three new publications on Australia’s China relationship and the US-China rivalry all implicitly claim the mantle of long experience and realism. But even that shared history of practical diplomacy by the three authors doesn’t necessarily provide any simple solutions to how Australia and the US should live with a rising new superpower. Nevertheless the ideas in these publications from quite diverse institutions do provide a useful framework for pulling back from the sense of crisis in the bilateral relationships fuelled by events such as the police raid on the residence of a pro-China NSW Labor politician. While they are far from aligned, all three authors accept that China will retain its authoritarian system while playing a bigger role in the world. The challenge then is to remain engaged but to find ways to constrain some of the worst aspects of the way China operates.

Behm, a former public servant and political staffer, argues many Australians have lost track of this overarching objective amid a rising sense that any positive sentiment towards China is craven or disloyal. “It is easy for governments to disguise their inability to manage complex relationships by resorting to finger-pointing and name-calling. But the over-investment in emotion usually masks an under-investment in thinking. The stridency that distinguishes contemporary government pronouncements on China and Australia’s relationship with China is alarmist and alarming,” he says.

Varghese, a former Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade secretary and now University of Queensland chancellor, says: “Australia’s China policy cannot be written on a blank page. It must reflect not just our interests and ambitions but also the world as it is. International relations form a complex ecosystem. Not even superpowers can bend them to their will.” He says too much public debate is focussed on China inevitably overtaking the US, when we really should be preparing equally for either country to prevail in their global rivalry.

Dupont, who has held advisory positions in government, says: “Preventing, or mitigating, worst case outcomes will require the US and China to accommodate each other’s strategic interests. This won’t be easy because of diminished trust, their different world views, the systemic nature of their confrontation and domestic politics.” He warns against the hard decoupling of global supply chains in response to China’s assertiveness and the pandemic because that would worsen the economic downturn and probably create more arenas of conflict. But a managed decoupling would protect the liberal international order and encourage China to see the value in that system for it.

ON THE HORIZON

SINGAPORE: LEE v LEE?

Lee Hsien Yang (centre) on his first day as a Progress Singapore Party member.

Singapore goes to the polls on July 10 for another of its fast turnaround elections which often leave the increasingly fragmented opposition parties struggling to present a coherent alternative.

But this election may be more interesting than most, with the People’s Action Party (PAP) government under some pressure over the way it lost its early control of the COVID-19 pandemic due to failing to manage the spread through its apparently overlooked migrant worker communities. And the country’s gradual shift towards some more election contestability has been underlined by a formal split in Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s own family, with his younger brother Hsien Yang joining the relatively new Progress Singapore Party (PSP).

The PSP is set to run more candidates than the much longer established traditional main opposition Workers’ Party. But with 11 opposition parties contesting the 93 seats amid a campaign constrained by the pandemic, the anti-government messaging seems likely to be diffused. Rallies – which the opposition parties have used to successfully drum up support in past elections – will be banned this time due to social distancing rules, leaving the opposition to campaign in the media and online space where the government can exert more control.

When the early election was first touted by the government as necessary to help push forward with recovery from the pandemic, it was being lauded for its early control measures. But the lockdown forced by the subsequent infection outbreak means the economy is now likely to contract by about six per cent this year – one of the sharpest downturns in the region. The government has now embarked on one of the largest fiscal stimulus programs by GDP share in Asia, funded from the country’s large and publicly undeclared financial reserves. The spending is about S$90 billion or 20 per cent of GDP. In an interesting insight, one opposition party last week claimed the government had S$1.5 trillion in reserves under its control. That would be about ten times the size of Australia’s Future Fund, although the Singapore economy is about one third the size of Australia.

ABOUT BRIEFING MONTHLY

Briefing MONTHLY is a public update with news and original analysis on Asia and Australia-Asia relations. As Australia debates its future in Asia, and the Australian media footprint in Asia continues to shrink, it is an opportune time to offer Australians at the forefront of Australia’s engagement with Asia a professionally edited, succinct and authoritative curation of the most relevant content on Asia and Australia-Asia relations. Focused on business, geopolitics, education and culture, Briefing MONTHLY is distinctly Australian and internationalist, highlighting trends, deals, visits, stories and events in our region that matter.

We are grateful to the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas for its support of the Briefing MONTHLY and its editorial team.

Partner with us to help Briefing MONTHLY grow. For more information please contact [email protected]

This initiative is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.