'Gorgeous'

'Beautiful ... Riveting'

– Tricycle

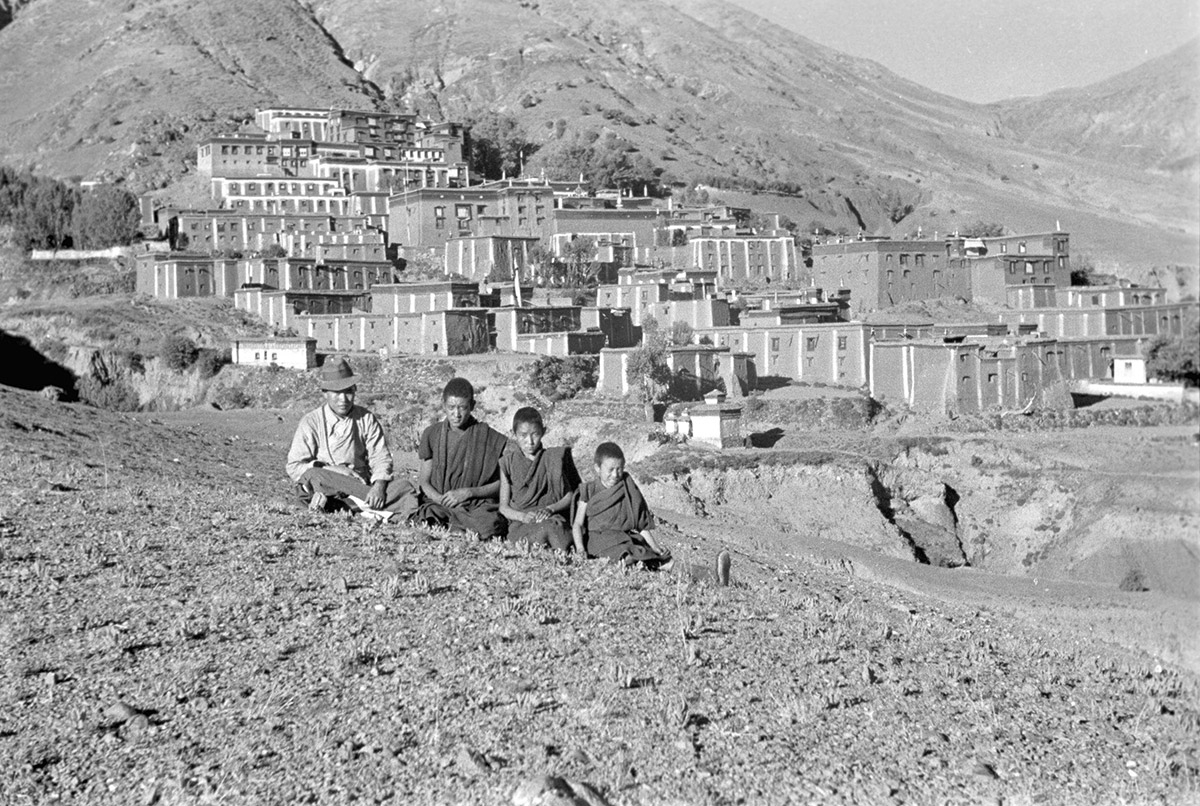

Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting features stunning paintings collected by Italian scholar Giuseppe Tucci during his 1926-1948 expeditions to Tibet, and striking photography of his travels. The paintings — on loan from the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci," Rome — are on view for the first time in the United States.

Guest curator Deborah Klimburg-Salter, University Professor Emeritus, CIRDIS, Institute for Art History, University of Vienna; and Associate, Department of South Asian Studies, Harvard University; with Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art, Asia Society.

Purchase the richly illustrated book featuring works from this exhibition and more at AsiaStore.

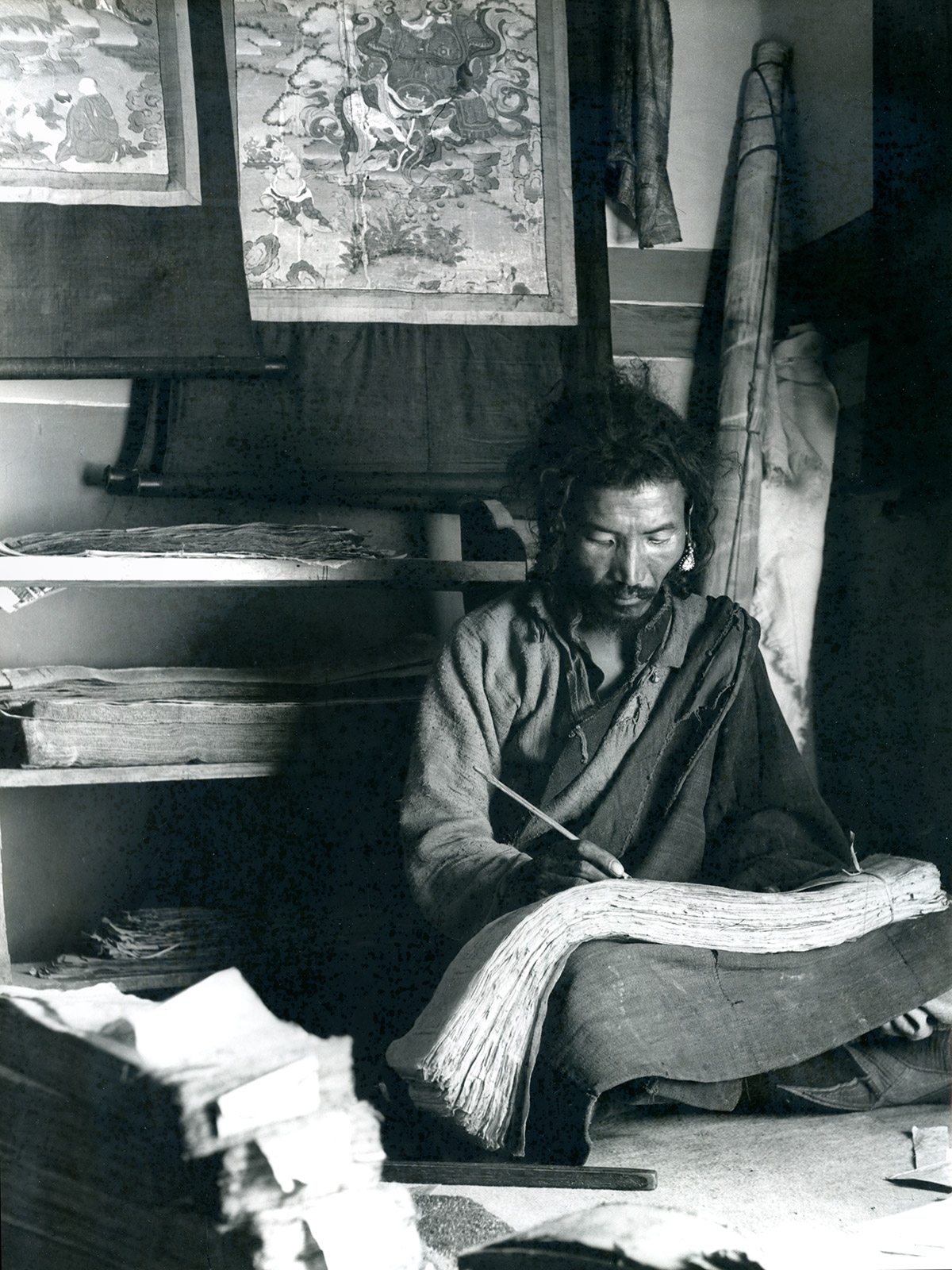

The world knew very little about the Himalayan region when Italian scholar and explorer Giuseppe Tucci (1894–1984) began his work around one hundred years ago. His contributions to the understanding of Tibet, including Tibetan Buddhism, in the West have been enormous and the materials he was able to gather for future study impressive. Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting presents a selection of the paintings he acquired during his travels. Tucci obtained expedition permits that included permission to acquire and export original source materials for scientific study. The paintings he acquired were purchased, gifted, or found and deemed too badly damaged or incomplete for cult use by the Tibetan communities. Those in this exhibition, all recently conserved, are now in the collection and care of the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art “Giuseppe Tucci” in Rome, to which Tucci and his wife Francesca Bonardi Tucci bequeathed all of their possessions.

Tucci’s life was framed by two World Wars, a worldwide economic depression, and—shortly after his last journey to Tibet—the destruction of Tibetan monastic culture. The turbulent times and the four years Tucci spent in the military during World War I—two of which were at the front line—had a profound effect on him. He was a highly intellectual, multi-lingual scholar with an antipathy to military solutions and a dedication to the pursuit of intercultural dialogue. During his lifetime, he received many high honors from many countries in Europe and Asia, and his scientific legacy is still fundamental to the research of Tibetan culture today. Tucci’s bibliography of more than four hundred entries attests to the expansiveness of his interests and talents.

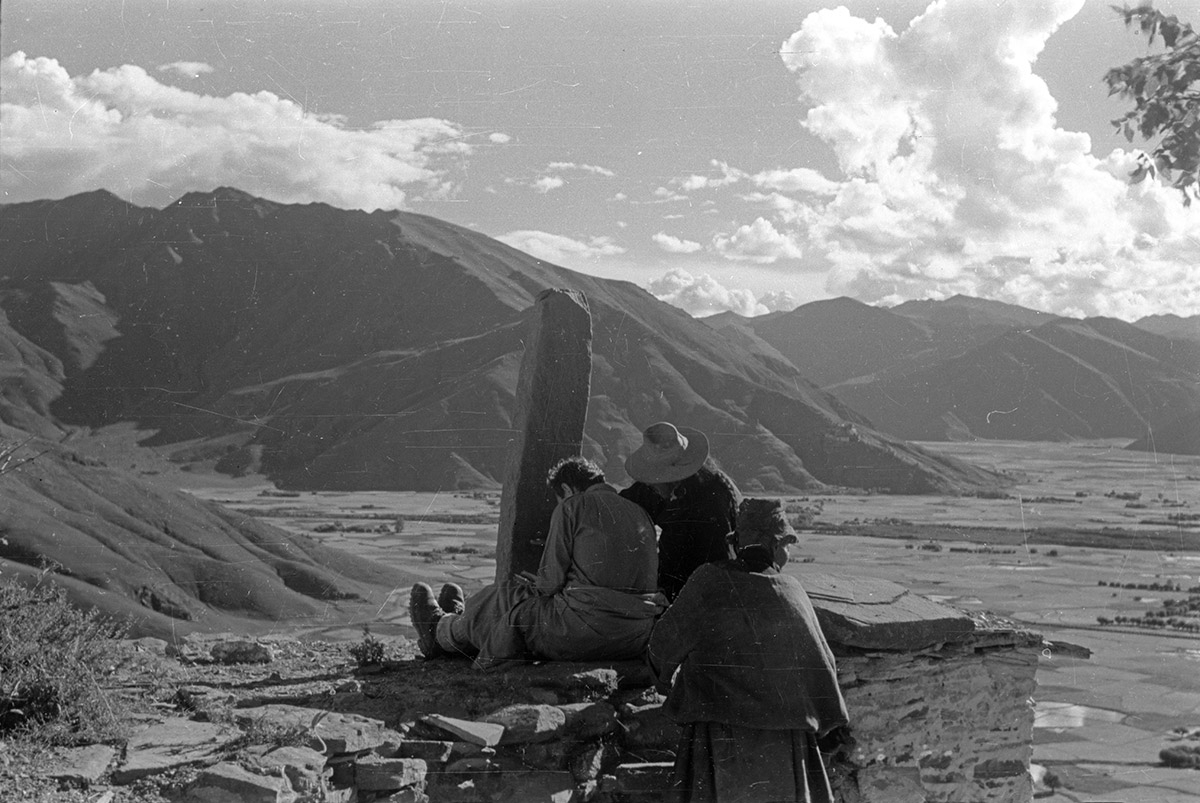

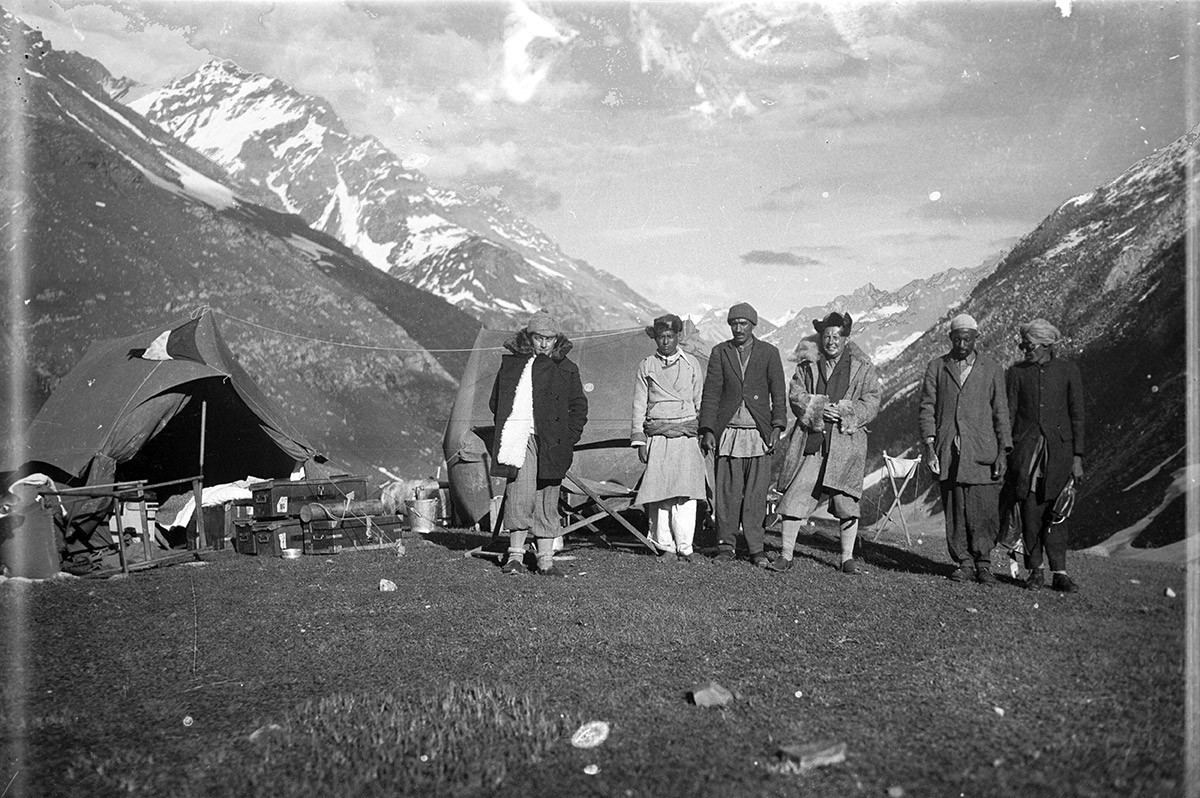

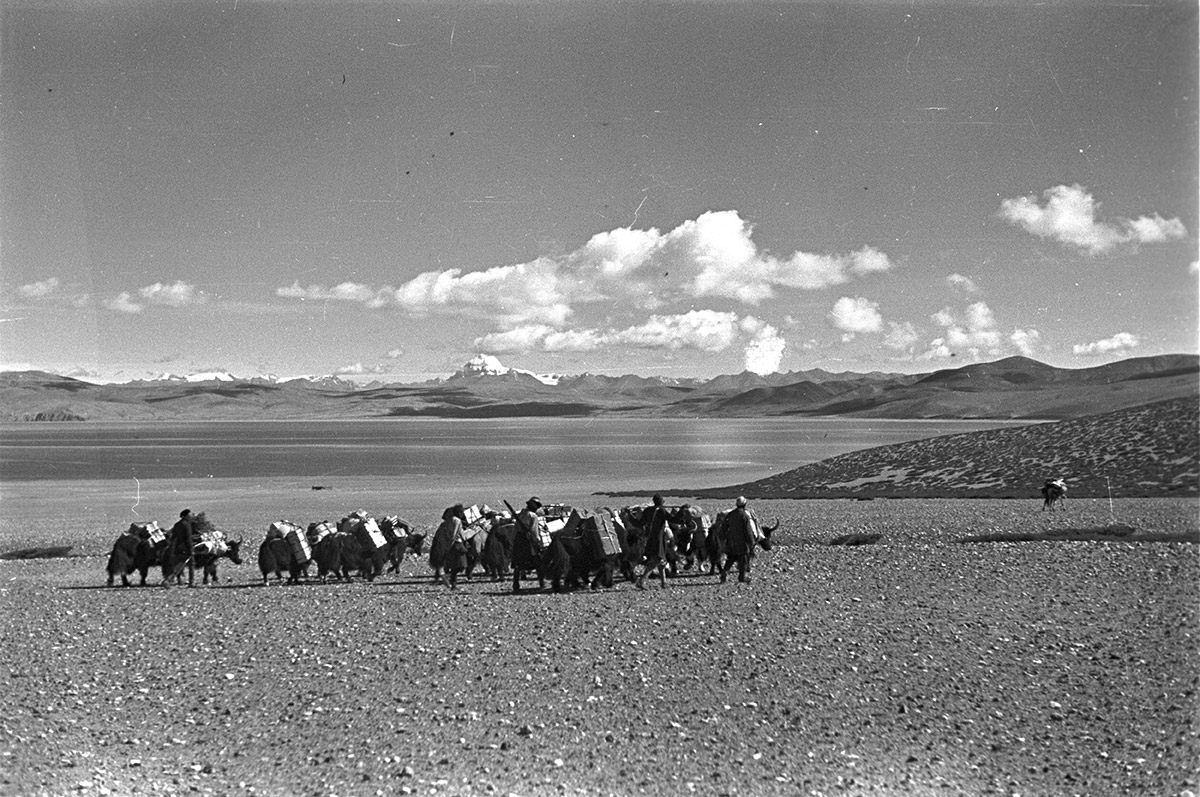

Tucci was also one of the most important explorers of the century. Among his scientific travels were eight major expeditions to Tibet, from 1928 to 1948, which are the focus of this exhibition. The selection of paintings and reproductions of photographs from three Italian photographers represent the roughly five thousand miles Tucci trekked across the Tibetan cultural zone, which extends far beyond the present borders of the Tibetan Autonomous Region in China. They also challenge us to envision very distant points in time and place: Italy at the beginning of the twentieth century, pre-modern Tibet, and the culture of ancient Tibet that expanded and blossomed from the twelfth century.

Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting was organized by the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art “Giuseppe Tucci,” Rome. Unless otherwise noted, all objects in the exhibition are on loan from MU-CIV/MAO “Giuseppe Tucci,” Rome.

Guest curator Deborah Klimburg-Salter with Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art, Asia Society.

A Selection of Photography From Tucci's Expeditions to Tibet

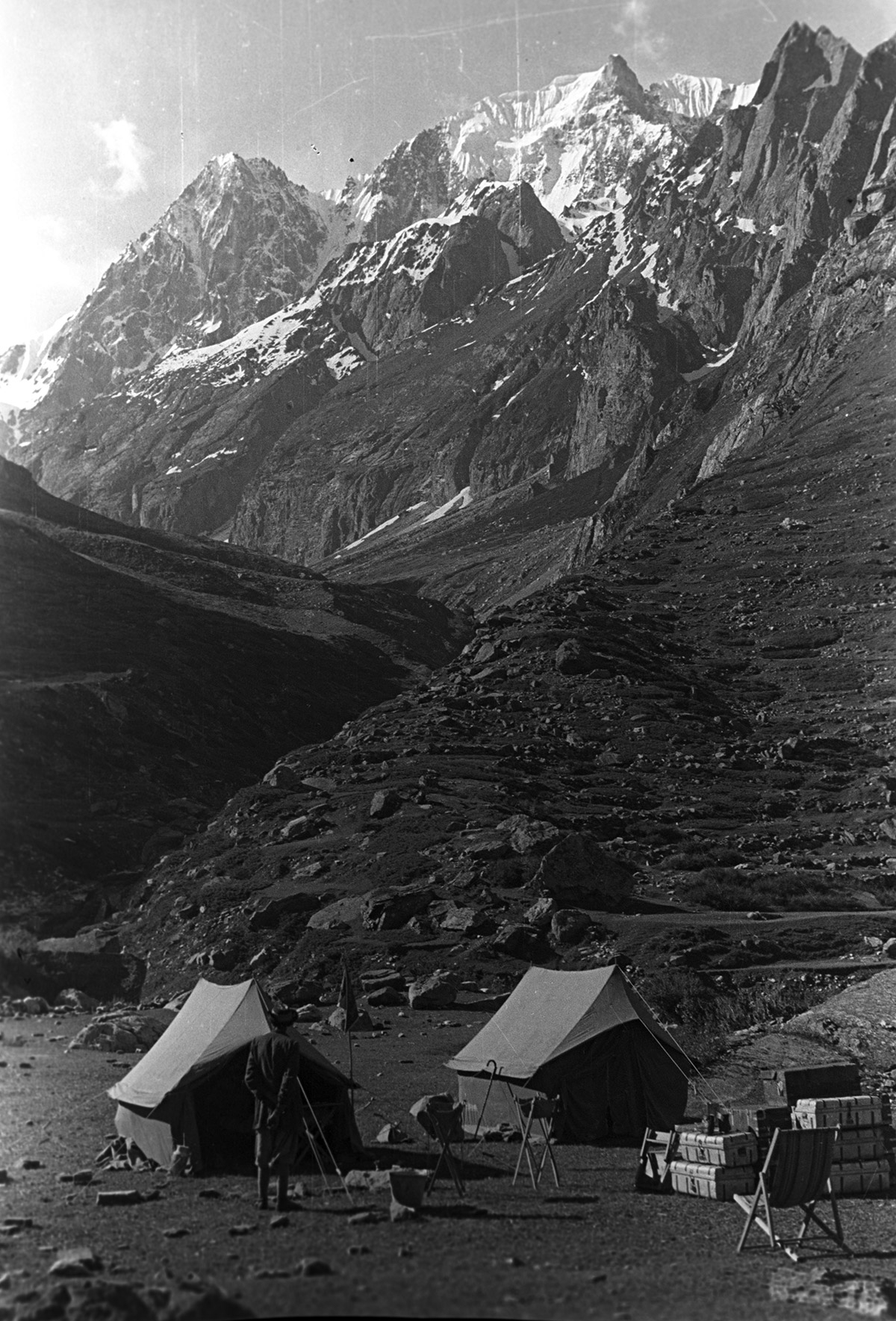

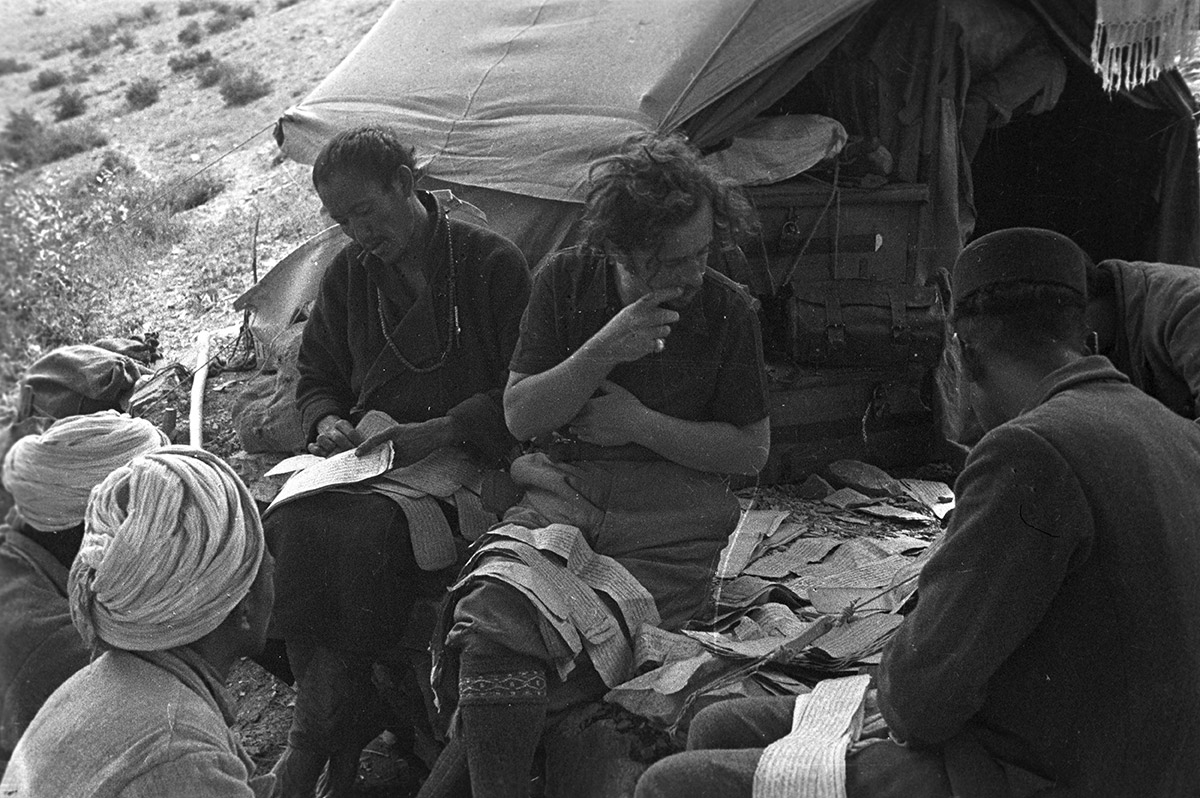

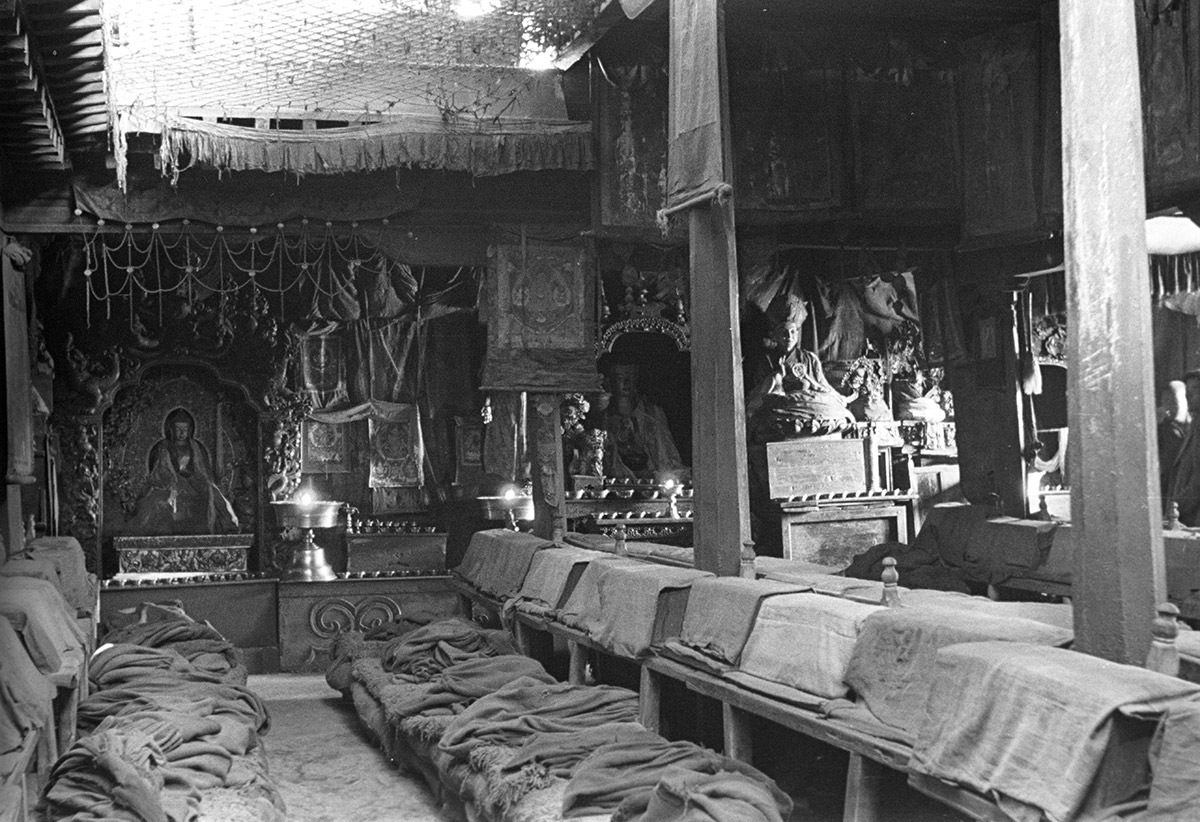

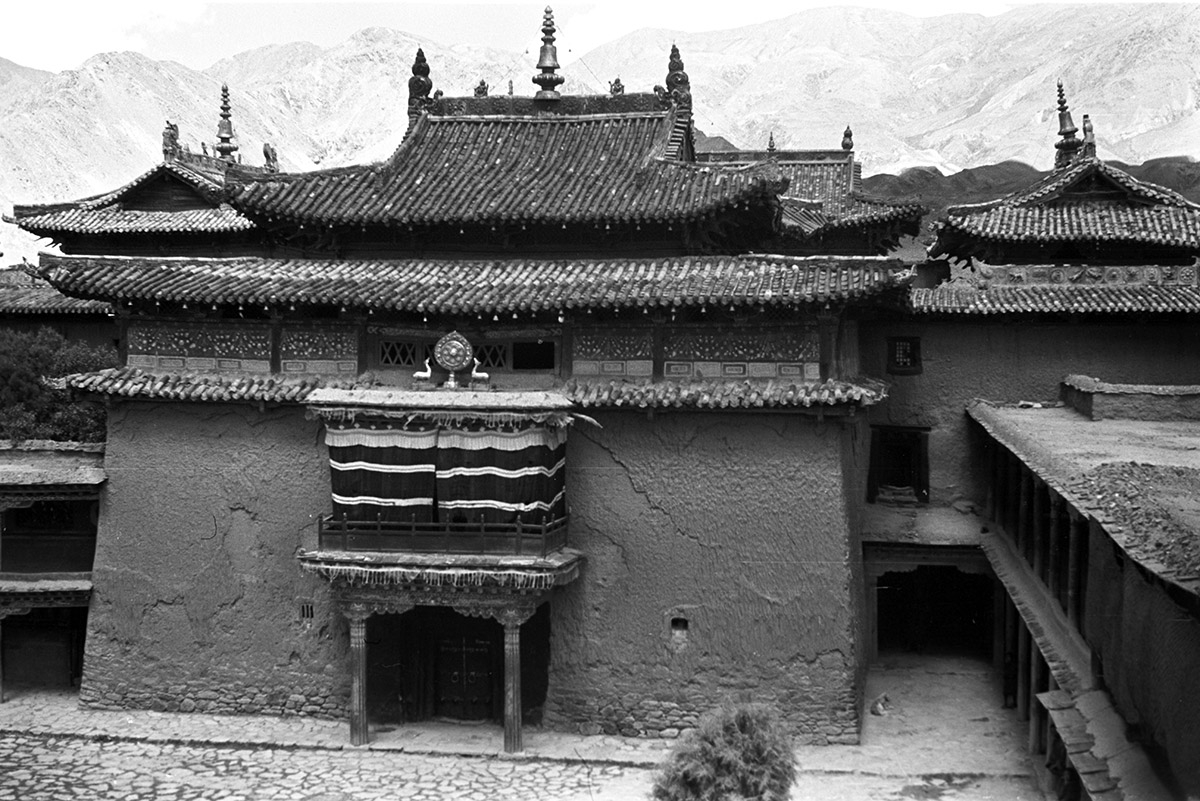

The photographs included in the exhibition resulted from Giuseppe Tucci's eight Tibetan expeditions (1928-1948), which each averaged six months and not only were complicated to organize and provision, but also expensive. Tucci traveled under the Italian flag to facilitate negotiation for permits with other governments, and he struggled to secure public and private contributions. His failed attempts at documenting his earliest journeys with photography convinced him that each expedition needed a dedicated photographer with the skills to photograph in challenging environments-even inside dark monuments-and to develop the film along the way.

Concerned with the desperate condition of much of Tibet's cultural heritage, and receiving no response to his requests to the British government in India for preservation measures, he championed the most extensive, systematic photo-documentation effort ever made across the entire Tibetan cultural sphere. His expedition photographers were instructed to record monuments, cultural artifacts, and people and their occupations. The goal, Tucci wrote, was "the revealing and preserving, in so far as the record of photography may preserve, the remains" of this ancient civilization. The selection of photographs includes representative images of landscapes and towns, as well as monasteries where the paintings in this exhibition were created, displayed, or acquired by Tucci.

Covering nearly five thousand miles on foot and horseback across the most difficult terrain and the highest plateau on earth was no easy task, and required that the photographers also needed to be adept mountaineers. Eugenio Ghersi, who accompanied two expeditions-1933 and 1935-was not only a photographer and mountaineer, but also a surgeon, hobby cartographer, and beer brewer. A uniquely talented and loyal travel companion to Tucci, Ghersi was the only photographer to keep a detailed diary of their journeys. The 1937 expedition photographer was the twenty-five-year-old Fosco Maraini, while Felice Boffo Bellaran was the photographer for the 1939 expedition. The long 1948 expedition to Lhasa and Central Tibet included the physician and photographer Regolo Moise, in addition to the photographers Pietro Francesco Mele and Prodhan, a Sikemese.

Today the majority of 14,000 prints, negatives, and fragments of film from the expeditions have been cataloged by The Tucci Photographic Archive project sponsored by IsMEO and now housed in the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci."

The Path of the Sutra and the Path of the Tantra

The majority of paintings in this exhibition are religious paintings that are meant to serve as supports for meditation and ritual. They are intended to assist the practitioner on the path to awakening, or the attainment of bodhi, often called enlightenment. Tibetans recognize two paths of the Mahayana, which provide the primary structure for this exhibition. The goal of Mahayana is the attainment of Buddhahood for oneself and all sentient beings. The Path of the Sutra, path (yana) Sutrayana, or Paramitayana. The second path is Tantrayana, the esoteric path, or Path of the Tantra, also called Vajrayana or Mantrayana. Each path is based on different sacred texts. A sutra is a discourse attributed to a Buddha (often the historical Shakyamuni Buddha); a tantra is a discourse attributed to a tantric transformation of the Buddha that contains philosophical principals as well as instructions for ritual and meditation. Tibetans believe that the development of compassion combined with the distinctive meditational practices of the Path of the Tantras offers a quicker path to enlightenment.

The paintings in the exhibition are presented in six groups according to the invocation recited at the beginning of the Buddhist daily prayer in Tibet. All Buddhists begin their daily practice by taking refuge in the Three Jewels, which are fundamental to the Sutrayana in all Buddhist traditions: the Buddha (Shakyamuni Buddha); the Dharma (the Buddhist teachings); and the Sangha (the Buddhist community). In Tibet this invocation is often expanded to include the Three Roots of Tantrayana, so that the practitioner additionally vows to take refuge in the Lama (Guru); the Yidam (a personal meditational deity); and the Protectors (of the Dharma and the practitioner).

Thangkas are devotional paintings dedicated to the figure placed at the center of the composition who is always larger than all other figures in the image. Within the categories of the Three Roots, this figure can be a Lama, a Yidam, or occasionally a Protector. Highly esteemed lamas appear at the top of many thangkas, representing the transmission of the teaching manifested in the painting. The Protectors of the Dharma are placed at the bottom of the thangka. An image of the practitioners and donor of the painting is sometimes found at the bottom of the painting as well, together with the lamas who perform the rituals associated with the painting.

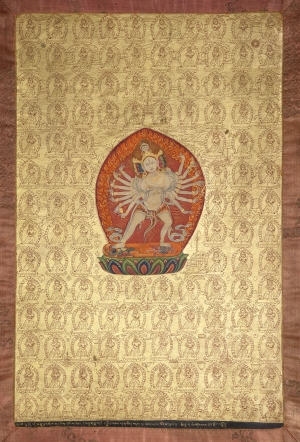

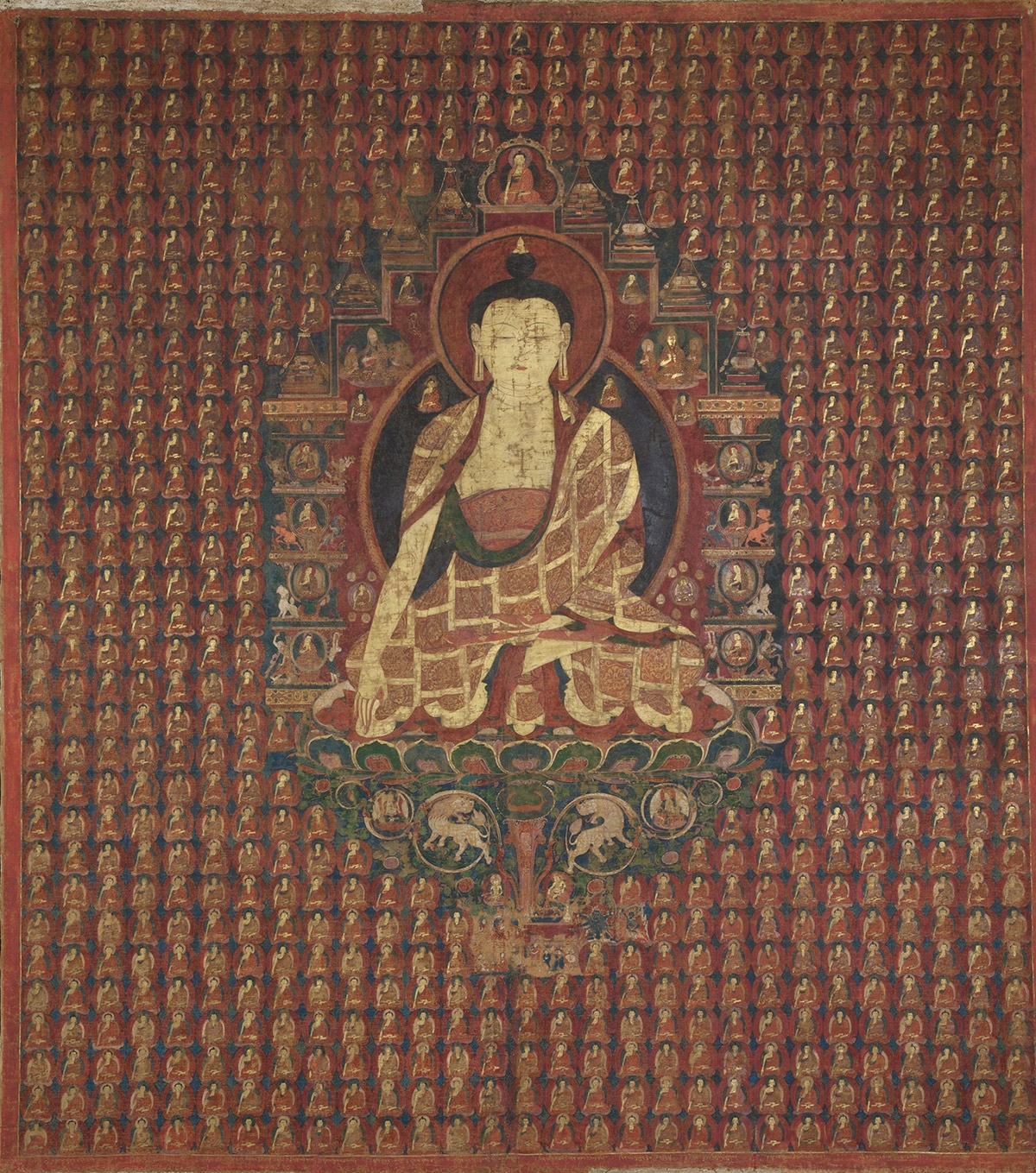

Amitayus. Ca. 16th century. Tsaparang or Tholing, Ngari (West Tibet). Tradition: Gelug. Pigments on cloth. MU-CIV/MAO 'Giuseppe Tucci,' inv. 1011/837. Gift of Oliviero and Marzia Corcos. Image courtesy of the Museum of Civilisation/Museum of Oriental Art 'Giuseppe Tucci,' Rome.

The subject of this painting is Amitayus, one of the three Long Life deities in Tibetan Buddhism. Amitayus is the emanation of Amitabha, the Jina Buddha of the West. Amitayus floats here in the middle of a cosmos inhabited by hundreds of tiny repetitions of himself. The composition is dominated by red, the color of the family of Amitabha Buddha. Amitayus holds the bowl of Amrita, or elixir of immortality, which flows down over the lotus throne and onto King Jigten Wangchug (d. 1540) and his eldest son Naggi Wangchug. The king patronized temples filled with monumental sculptures and mural paintings in Tsaparang, the capital of the Kingdom of Gu ge.

A sutra is a discourse attributed to a Buddha, usually Shakyamuni Buddha. The most frequently encountered image in all Buddhist art is the iconic image of Buddha seated in meditation and dressed in monastic robes. This image was first developed in India where the teachings of the Buddha originated.

In Tibetan painting the iconography of the Buddha remains true to its Indian origins. The Buddha is often depicted with two attendants, usually his two principal students, one to each side, as in the fifteenth-century painting in this section. Buddhists study the spiritual biography of the Buddha as a paradigm for the progress to enlightenment.

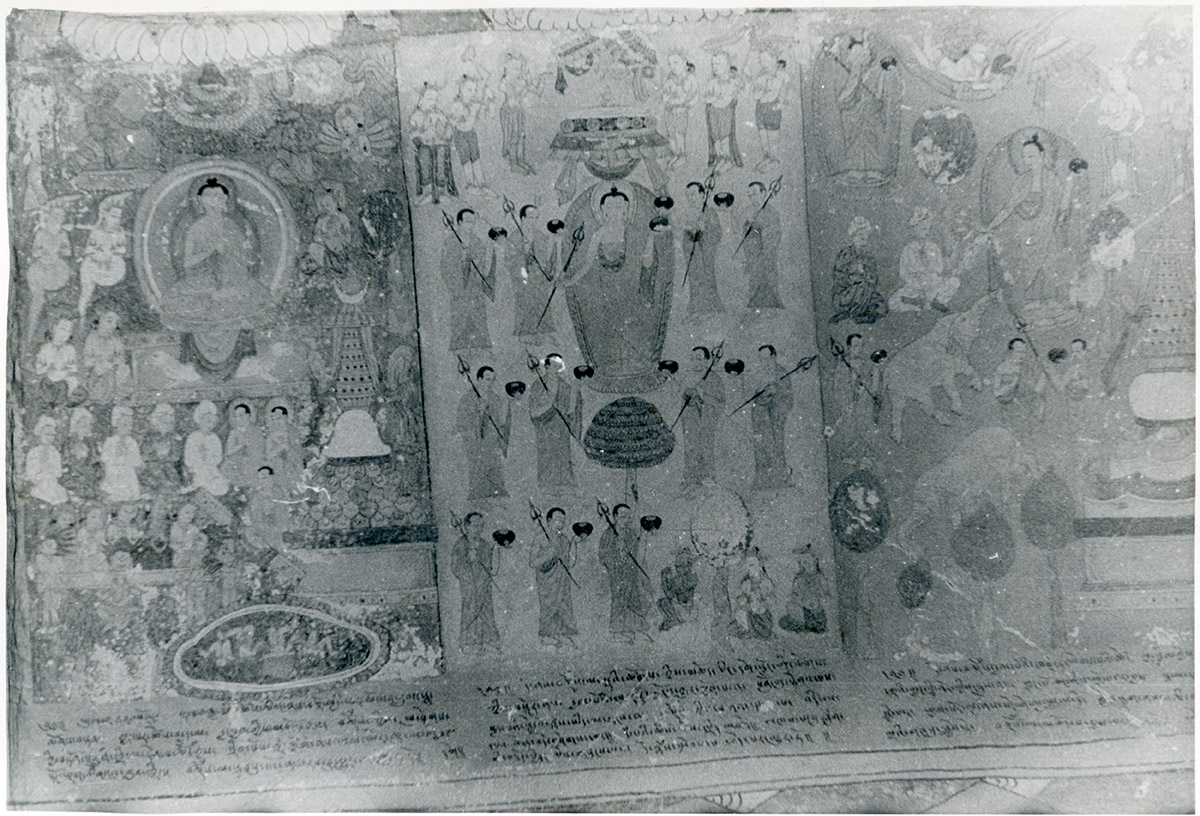

This important thangka has an inscription in gold along the bottom margin that includes a rare mention of an artistic school-the Kashmiri tradition-in addition to a quote from the Bhadrakalpikasutra. Originally hidden under the silk frame, the inscription would never have been seen by anyone. The subject of this painting is the bhadrakalpa, an "auspicious age" in which there are one thousand buddhas. The style of the painting is closely related to that found in wall paintings in the temples in Tholing and Tsaparang, the religious center and the capital, respectively, of the Kingdom of Gu ge, West Tibet, which Tucci visited, documented, and photographed during his 1933 and 1935 expeditions.

Tucci acquired this thangka during his 1933 visit to Luk Monastery in Ngari, West Tibet. His accounts praise the high quality of artworks in Luk Monastery. There are two lineages represented in this painting-that of the Gelug tradition and of the Kagyu tradition. Each lineage begins with the primordial buddha, Vajradhara, who is positioned at the center of the top row. Five Gelug tradition lineage holders are depicted to the right and ten Kagyu tradition lineage holders to the left. The small number of lamas shown in the Gelug tradition lineage indicates that the thangka must be from a relatively early date.

In this image Shakyamuni is dressed in the patchwork robe of a monk and is seated in meditation posture on a lotus. Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelug tradition, is depicted directly above Shakyamuni. They are each flanked by their principal disciples. The names of Shakyamuni's disciples appear below each in gold. They are Sha ri bu (Sariputra) and Mon gal bu (Maudgalyayana). Another inscription on the right, below Shakyamuni's lotus throne, may be translated "I prostrate myself to Shakyamuni."

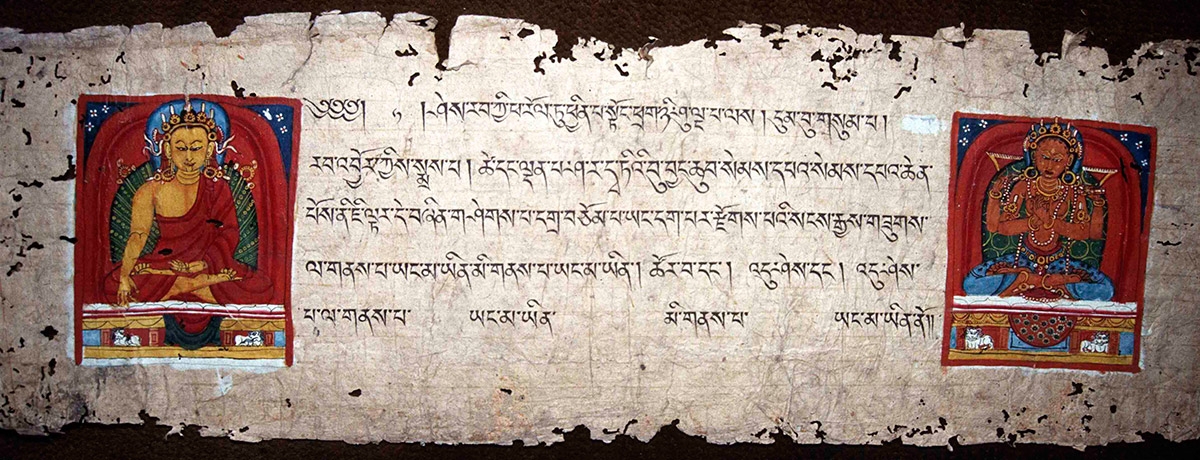

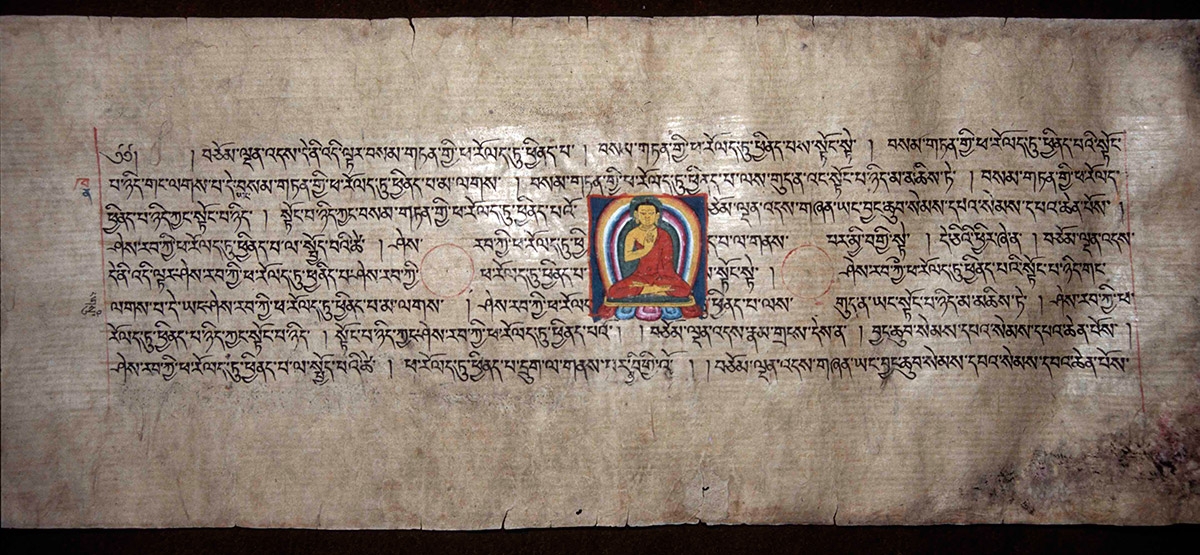

The Buddha's teachings (dharma) are known as the Buddhadharma. In this gallery the teachings of the Buddha are presented in manuscript form. The Perfection of Wisdom, or the Prajnaparamita, is a Mahayana sutra first written in Sanskrit. It was translated for the first time into Tibetan during the Period of the First Dissemination of Buddhism in Tibet (7th-9th centuries) and became extremely important in Tibet. As is seen in the two examples on this panel, the text has different forms distinguished by the length of the text.

In 1933, when Tucci's expedition photographer Eugenio Ghersi climbed up the mountain next to Tholing Monastery in order to take a photograph, he found a cave where folios from incomplete religious manuscripts had been buried. According to tradition, when sacred texts or images can no longer be used for cult purposes because they are defective they must be properly disposed of, such as by burial.

The female Bodhisattva Prajnaparamita, the personification of the text, is frequently painted as in the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century folio from a manuscript that was no longer complete and thus could not be used for religious purposes and was retrieved from caves high up above Tholing Monastery in West Tibet.

Sacred works of art are intended to support the efficacy of the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha. Sacred manuscripts such as these support the speech of the Buddha (gsung rten) as a means to transmit the Buddhist doctrine (Buddhadharma). This page is the first folio from a handwritten Tibetan manuscript of the Pancavimshatisahsrika Prajnaparamita, or The Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom in 25,000 Lines. On one side of the page is the four-armed goddess who is the personification of the Prajnaparamita text. She holds the book in her upper left hand and her upper right hand holds prayer beads. On the opposite side of the page is an image of Shakyamuni Buddha. His golden skin is one of the eighty-four auspicious signs of a so-called "great being."

Tucci found this folio with other fragments of a Shatasahasrika Prajnaparamita, the Tibetan translation of the original Sanskrit Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom in 100,000 Lines, in a cave located high above Tholing Monastery in West Tibet. The Prajnaparamita Sutra has several different versions that are identified according to their length; the longest is the Shatasahasrika. The archaic forms of Tibetan orthography suggest the relatively early date of this folio and that it was copied from a Tibetan translation prepared during the Imperial Period from the seventh to the ninth century. All the formal features of this manuscript page are characteristic of early canonical manuscripts from West Tibet, for example the style of the gold-skinned Buddha and his five colored mandorla. The two circles are reminders of the string holes used in the earliest canonical palm-leaf manuscripts, and the red and blue letters in the upper left hand corner identify the number of the volume.

The Sangha refers to the Buddhist community, including religious leaders, monks, and nuns, whose role is to preserve the Buddhadharma. In this gallery the Buddhist Sangha is represented by an incomplete but spectacular set of Arhat paintings from the seventeenth century. Arhats are believed to be monks who were among the earliest disciples of the Shakyamuni Buddha. They are considered to be perfected beings. And although spiritually realized, they remain on earth in order to protect the Buddhadharma.

Thirteen of the sixteen Arhats are believed to have belonged to the original Buddhist Sangha and were entrusted by the Shakyamuni Buddha to protect and propagate his teachings. According to the Buddhist tradition, each Arhat occupies a particular position in the cosmos and together the Arhats protect the universe. In addition each Arhat has a specific place in the spiritual biography of the Buddha, as can be seen from their life stories.

Traditionally a series of painted Arhats like the one this section would be placed inside the temple at the top of the wall around the altar. This set is unique because the original golden veils and blue silk frames have been preserved. They still bear notations in ink on the back that indicate where each painting is meant to be hung relative to a central image of the Shakyamuni Buddha. In this installation an Indian sculpture of the Buddha takes the place of the missing central painting. The Arhats are arranged according to the numbering system written in Tibetan on the back of each painting. There were originally eight Arhat paintings on each side of the central image, but two Arhats are also now missing from the right side. The first painting is placed to the Buddha's right. The first Arhat is followed by the paintings in the second through eighth position. The next painting is placed to the Buddha's left and the remaining seven paintings in the set follow.

Ajita Arhat, one of the thirteen original disciples of the Buddha, is shown here in his meditation cave on Mount Trangsrong. He is said to have been able to inspire discipline and deep meditation in everyone who saw him. The outer shawl of his monastic robes is pulled over his head, indicating that he is meditating. He is one of four Arhats responsible for protecting the Buddhadharma and practitioners who inhabit the western part of the Buddhist cosmos.

Vanavasin was one of the original followers of Shakyamuni Buddha and was personally initiated by him. He is said to inhabit a retreat on Saptaparni Mountain in India with his retinue of 1,400 Arhats. The tiger at his feet represents his isolated wooded retreat, where he meditates in solitude. He is one of four Arhats responsible for protecting the Buddhadharma and practitioners in the western part of the Buddhist cosmos.

Kalika Arhat holds two large earrings which, according to legend, the gods of the Kamadhatu gave to him when he ascended to teach the Buddhadharma. The earrings appear again in the hands of one of the two gods depicted making offerings at the bottom right of the painting. Kalika is said to live in Tamradvipa, a mythological land, with a retinue of 1,100 Arhats.

Vajriputra Arhat is said to reside with 1,000 Arhats on the island of Sri Lanka, perhaps suggested by the magnificent peacocks at the bottom of the painting. One of the original followers of the Buddha, he is one of the four Arhats responsible for protecting the western part of the Buddhist cosmos.

Cullapanthanka is the last, or eighth painting, on the Buddha's right-hand side. The two Arhats who occupied positions six and seven on this side are missing from the set. Cullapanthanka is said to have lived on Vulture's Peak, one of the Buddha's favorite spots for meditation, with a retinue of 16,000 Arhats. There, even wild animals were fond of listening to his discourses, as can be seen from the pair of birds to the Arhat's right and the dragon below them in the bottom corner. In this painting, a royal couple faces the Arhat and offers him a blue jewel.

Angaja is the first among the Arhats and therefore his painting occupies the first spot to the Buddha's right in this series. The Buddha is said to have miraculously delivered Angaja at birth, though his mother had died and was being cremated when he entered the world. At the age of twenty-eight Angaja was initiated into the Sangha by Shakyamuni Buddha. Here the snow-capped mountains and the sleeping snow lion indicate the Arhat's abode on Mount Kailasha with an entourage of 1,300 Arhats. The stream flowing down on the right reminds the viewer that Mount Kailasha is the source of many important rivers in the subcontinent.

Nagasena Arhat was born a prince in Northern India and belonged to the Kshatriya caste of warriors. One of the original followers of the Buddha, Nagasena is shown here holding his standard attributes: a beggar's staff and a treasure vase. He uses the staff to heal sickness and cleanses sentient beings of their sins with the vase, presented to him by the four kings of the four points of the compass. He is said to occupy Ngoyang, a sacred mountain, along with 1,200 followers.

One of the original followers of the Buddha, Panthaka Arhat was born in the holy city of Sravasti to a Brahmin family. According to tradition Panthaka lives in the Devaloka, a plane of existence inhabited by gods and celestial beings (devas), attended by 700 Arhats. He is one of the Arhats responsible for protecting the eastern part of the Buddhist cosmos. Here he holds a book as his attribute. The artists of these series often painted very imaginative interpretations of animals and heavenly beings. Here the marvelous miniature elephant to the Arhat's right has the paws of a lion and strangely formed ears, while in the opposite lower corner a heavenly being (Ghandarva) is dressed in leaves.

Kanakabharadvaja carries no attributes because he sits in meditation. He was born in the holy city of Sravasti and is one of the original disciples of the Buddha. He was known for his generosity and one source identifies the name of the place he dwells as Godhanya, where he is attended by 700 monks. He is also said to have an affinity for sweet music and fragrant smells. The symmetrical composition and lack of activity in this painting reflect the meditative atmosphere projected by the meditating Arhat. The pair of beautifully drawn cranes at the bottom of the painting demonstrate the reverence afforded him by birds and animals.

Bakula was born into a Brahmin family in Sravasti, one of the eight Buddhist pilgrimage places because it is the scene of miracles performed by the Shakyamuni Buddha. Bakula lives in the legendary land of Uttarakuru. In this image his attribute, a mongoose (nakula) sits on his left leg and expels gems from its mouth into the offering platter placed in front of the footstool.

Rahula is the natural son of Yashodhara and Prince Siddhartha, who became the Shakyamuni Buddha, and is one of the original followers of the Buddha. Rahula was initiated by Sariputra, one of the two closest disciples of Shakyamuni Buddha. The crown Rahula holds was a gift from the gods when he entered into the Trayastrimsa heaven to preach the Buddhadarma. Adherents of Buddhism believe he dwells on the mystical island of Priyanku accompanied by 1,100 Arhats. He is one of four Arhats responsible for protecting the eastern part of the Buddhist cosmos.

Pindola was born to a Brahmin family in Rajagriha, one of the eight holy cities and Buddhist pilgrimage places. He is said to be one of the original disciples of the Buddha and resides on the island of Sharluipapho in the eastern world attended by 1,000 Arhats. He holds an Indian-style book and a filled begging bowl. Pindola's miraculous powers enable him to grant special wishes to those who invoke him, such as the two supplicants by his right arm. The mythical animal dancing below his throne and the man holding a staff, perhaps from Central Asia, in the lower left corner enhance the atmosphere of the exotic and mystical. He is one of the four Arhats responsible for protecting the eastern part of the Buddhist cosmos.

Gopaka, born in Northern India into a merchant's family, is the younger brother of Panthaka Arhat. Gopaka Arhat lives on Vulture's Peak with 16,000 attendants. His attribute is an Indian-style book. At the bottom of the painting two expressive snow lions depicted in contrasting colors represent his mountainous abode.

Abheda was born in the holy city of Rajagriha into a Brahmin family. His attribute is the stupa which he holds in his hands. He is said to live with his 1,000 Arhat followers on the sacred mountain of Himavat (the Sanskrit word for the Himalayas), near the legendary land Shambhala. He does not sit on a throne but on a rocky outcropping, his Chinese-style boots resting on a stone. The setting symbolizes his distant secluded mountain abode. He was one of the original disciples of the Shakyamuni Buddha, who gave him the stupa in order to tame the dangers awaiting for him when he went to the northern countries to convert the nature spirits called Yakshas. A converted Yaksha with an exquisitely expressive face stands to the Arhat's right. Abheda is one of four Arhats responsible for the southern part of the Buddhist cosmos.

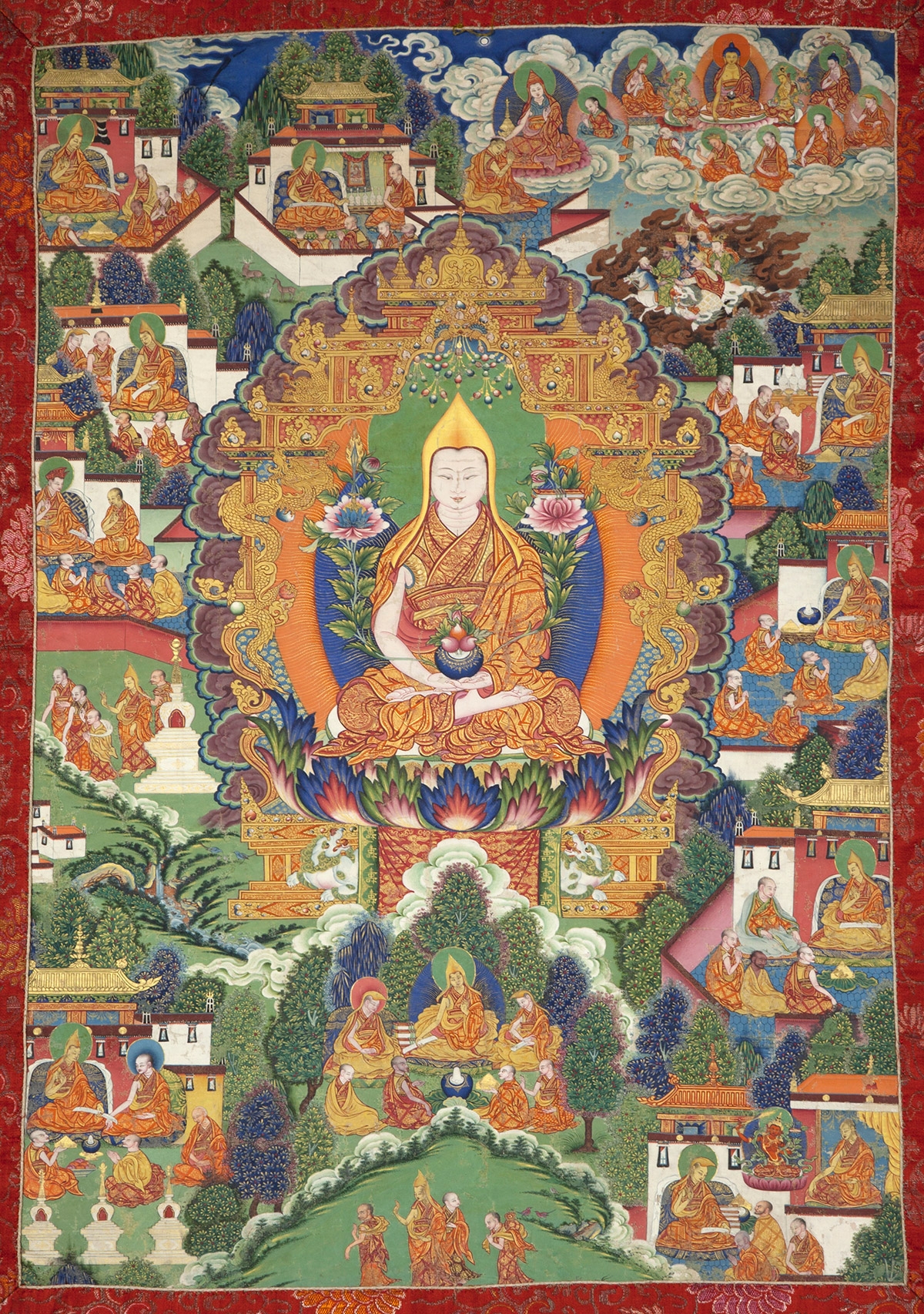

The Lama, the Tibetan designation for a spiritual master, holds a central position in preaching and explaining the Buddhist liturgy and meditation practices. In Tibet a large number of paintings represent the principal Lamas of the various Tibetan Buddhist monastic traditions. The thangkas in this exhibition include those of the Gelug, Sakya, Drikung, Nyingma, and Kagyu traditions. The lamas from the different traditions can often be distinguished by the specific hats they wear. For example the Gelug tradition, to which the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas belong, wear yellow hats. The other three major traditions-Nyingma, Sakya, and Kagyu-wear red hats.

For each of these traditions, every ritual text begins with an invocation that lists the entire lineage of transmission of the text. It is this lineage of lamas that establishes the authenticity of the teaching. The rows of persons, usually exclusively male, represented at the top and along the sides of the paintings in this gallery are the visual depiction of this invocation.

The transmission lineage begins at the top of each painting usually at the center, above the head of the central figure, but occasionally at the upper left, and continues down on each side. The line of transmission may begin with a deity, such as the primordial Buddha, Vajradhara, followed by one or more Indian Siddha, a perfected spiritual master who has attained psychic abilities, usually identified by his darker skin. The line may include a layperson, but usually the teachers are monks who wear the prescribed monastic robes.

Seated at the center of this painting is the eighth-century Indian Buddhist master Guru Rinpoche, Padmasambhava, the "lotus-born" teacher and scholar. Below this image is the Lotus King, Padma rgyal po, another form of Guru Rinpoche. Surrounding the central figure are twelve scenes representing Guru Rinpoche's teaching activities and the narrative of his invitation to Tibet.

Tucci recorded that he received this painting in Shalu Monastery, where the lamas assured him that the painting depicted the great fourteenth-century scholar-lama Buton Rinchendrub (1290-1364). His right hand is in a form of the vitarka mudra, indicating that he is teaching. At the bottom left of the painting, two standing lamas offer a mandala plate and a vase (bumpa) to the seated lama, who is conducting a tantric ceremony. The officiating lama is framed by a Chinese-style palace or temple which may refer to Shalu Monastery (founded in 1040), which was rebuilt by Buton Rinchendrub after being destroyed by fire.

In this painting the central image of Tsongkhapa is surrounded by scenes from his life beginning at the bottom center and proceeding clockwise. The painting is noteworthy for the remarkably fine and detailed renderings of people, architecture, and nature, and is unusual in that it is based on a wood-block series from U in Central Tibet. When the brocade borders were removed from this thangka during restoration, an inscription was revealed that identifies it as the third on the left of a series of paintings. Tucci purchased this painting at Kyi Monastery in Spiti, Himachal Pradesh.

This painting belonged to an important set of eight paintings representing the Sakya tradition teachers of the Lamdre rgyud lineage. This painting is the fourth in the set. Because this is the esoteric or tantric path of the Sakya tradition, not only were the teachers, or lamas, important but also the Mahasiddhas, or Great Adepts. Gold inscriptions on the red border of the painting identify all the figures. The four lamas, organized in pairs, are seated in meditation posture. Their dignified presence contrasts with the playful representations of the Mahasiddhas, often with their consorts, performing miraculous feats throughout the surrounding landscape. This contrast is a skillful visual, symbolic synopsis of the two aspects of the Sakya tradition's esoteric lineage: the esoteric teaching of the path and its realization.

The central figure in this painting, Lha'i rgyal po, the King of the Gods, is one of the previous mytho-historical persons in the incarnation lineage of the Dalai Lamas. The Avalokiteshvara Incarnation Lineage of the Dalai Lamas is a chain of rebirths beginning with Avalokiteshvara and progressing through several mytho-historical figures. The naming of the past lives of eminent lamas may be dated to the early twelfth century, but the elaborate Avalokiteshvara Dalai Lama Lineage dates to the lifetime of the Fifth Dalai Lama. Gold inscriptions assist us in identifying the secondary figures. This painting would have been part of a large series of thangkas, each representing one of the incarnations of the Dalai Lama Incarnation Lineage, typical of the school of the Gelug tradition.

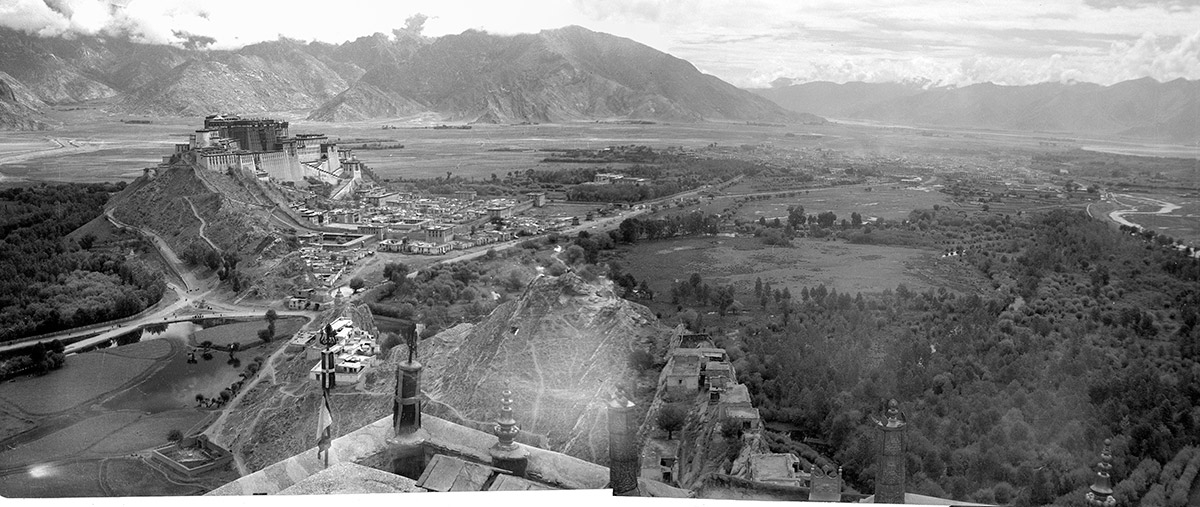

The most powerful political symbol of the Dalai Lama as an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara was the Potala Palace, named after the mythical residence of Avalokiteshvara, Mt. Potalaka, which is traditionally considered to have been located in southern India. In 1645 the Fifth Dalai Lama began construction of the palace on the site of the Emperor Songsten Gampo's seventh-century palace. The enormous complex was completed at the end of the seventeenth century by the Desi Senggye Gyatso, the Fifth Dalai Lama's last regent.

The yidam, or personal meditation deity, is understood to be a manifestation of Buddha-mind or an enlightened mind. Therefore the yidam is considered to be the Root of spiritual accomplishment. There are three forms of yidam-peaceful, semi-wrathful, and wrathful-and each has different characteristics. The most common type of peaceful yidam is one of the five Jina Buddhas. The Jina Buddha sits in meditation and is sometimes dressed in royal finery, but above all can be identified by his hand gesture and the color of his skin (white, yellow, green, blue, or red). Each of the Jina Buddhas is associated with a family of deities who are depicted in the same color. Another peaceful yidam featured in two paintings in this gallery is Tara, who has always been a very popular cult figure in Tibet.

Only a yidam can occupy the center of a mandala. The yidam assumes a wrathful appearance when extraordinary powers are needed. These paintings serve to support the visualizations that are part of the meditational and ritual practice of the Path of the Tantra.

This painting combines two forms of Tara as Savior as well as twenty-one Taras into one image. The large Tara at the center is flanked by her companions Marici on her right and Ekajata on her left. Her role as protector of eight perils is included at the edges and bottom of this work. Tara is considered both a bodhisattva and a buddha, and in her various forms she helps practitioners overcome difficulties on their path to enlightenment. The dense composition and vibrant coloration indicate that this magnificent painting was created either in Central or South-Central Tibet. The costumes of the donor figures at the center of the bottom row, and the architectural frame above Tara, which may refer to Shalu Monastery, both suggest a South-Central Tibetan origin.

Chakrasamvara is the main deity of the so-called Mother Tantras, a class of esoteric sacred texts within the category of the Highest Yoga Tantras (the Anutaratantra). Chakrasamvara is shown here in union pose with Vajravarahi, known in Tibetan art as yab yum, father-mother pose, and is a symbol for mystical union that developed out of Indian and Tibetan esoteric thought. It is not present in the Buddhist art of other cultures. Located at the bottom of the thangka, slightly left of center, a practitioner is depicted performing his daily ritual practice. He is most likely the man who commissioned this and the other paintings in the original series. Chakrasamvara was likely the donor's personal meditation deity, or yidam, as the entire series is dedicated to Chakrasamvara. This painting purportedly came from Sakya Monastery in South-Central Tibet.

Tucci acquired this painting in Narthang in South-Central Tibet. The distinctive stylistic features, such as the lotus base with fringed petals, suggest that the painting was also created in this region. The painting is dedicated to the yidam, or personal meditation deity, Dorje Jigje (Vajrabhairava in Sanskrit). He is represented here as the "lonely hero," that is without a consort. In this image Dorje Jigje is surrounded by a representation of the eight charnel grounds that, as Tucci explained in Tibetan Painted Scrolls (1949), symbolize "the eightfold conscious activity which keeps us bound to life and hence to death." Sakya lineage figures and deities frame the image. At the bottom left of the painting the donor of the painting is depicted in a scene that probably represents the ritual consecration of the painting. The donor, his family members, and the officiating lama are seated under a blue and red canopy. The donor and a woman that is probably his wife wear the elaborate dress and headgear associated with the nobility of Tsang during that period.

This extremely fine and well preserved painting appears to have been inspired by a fifteenth-century painting from Ngor Monastery of the Sakya tradition. The schematic presentation of the lamas and other figures surrounding the central mandala, however, suggests a later date of the sixteenth to eighteenth century. This mandala features the wrathful Chagna Dorje embracing his partner Dorje Dzedenma. His feet trample on Brahma and Chandra, who symbolize non-Buddhist beliefs that need to be overcome. Eight charnel grounds that symbolize the eight kinds of sensual or mental activities, along with a fire circle, surround the lotus of the mandala. The row of figures at the top of this painting represent the Sakya lineage that handed down the teaching of this mandala. The row at the bottom of the painting includes an offering scene between the protector deities.

Those who follow the Path of the Tantra also rely on Protectors of the Dharma and Practitioners, who are the Root of enlightened Activity. In the daily invocation the Protectors are asked to protect the mandala that is the sacred space in which the ritual takes place. In the graphic mandala that is often represented as a Palace Mandala, the Protectors guard the four gates to the center of the mandala. This symbolism derives from built architecture where sculptures of Protectors flank the entrances to sacred spaces, such as temples.

The Protectors of the Dharma is a large category and the only one presented in the exhibition that is defined slightly differently by each Tibetan tradition. Each school has preferences for specific Protectors, for example Palden Lhamo is the preferred Protector of the Gelug tradition.

This compelling painting with its strong and simple composition and subtle color palette is the earliest in the Tucci collection from the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci" in Rome. The figure at the center of this painting is Vaishravana, the king of the north, represented in his form as a wealth-bestowing deity. He holds a club crowned with a wish-granting jewel and a bag in the form of a mongoose spitting out pearls. The small nagini to his left is his consort, Pema Tsukpuma. This painting was originally part of a larger group of paintings dedicated to the gods of wealth. Tucci appears to have acquired this painting at Ngor Monastery in South-Central Tibet. The archaic figure style, the simple geometric composition with minutely depicted secondary figures isolated in square fields, and the small number of lamas in the top row of the painting all suggest an early date around the fourteenth century.

This dramatic "Black Thangka" shows the wrathful deity Palden Lhamo surrounded by whorls of smoke and fire painted in gold and red. Palden Lhamo, the most important protectress of Tibet, is also the protectress of the Gelug tradition, and the principal guardian goddess of the city of Lhasa. Here, she appears as the Army-repulsing Queen. She is mounted on a mule saddled with a human skin and who has an eye at the base of its tail. At the upper right of the painting is a practitioner of the Gelug tradition performing the ritual associated with Palden Lhamo. The aesthetic impact of this thangka is reinforced by the original silk and brocade frame.

Tucci obtained this painting in Nako Village in 1933 in Kinnaur, India, an area that from the tenth century was the western most district of the powerful Kingdom of West Tibet. While the wall paintings from the five surviving temples of Nako from the early twelfth to eighteenth century testify to a vibrant and distinctive painting tradition, this is the only early portable painting that can be definitely attributed to Kinnaur. The subject of this painting is a mythical bird known as a Garuda. A Garuda protects against negative influences, especially poisons. In Buddhist philosophy the three poisons are defined as attachment (craving), hatred, and delusion (ignorance). The primary colors and archaic composition and figure style seem to reflect earlier Tibetan ritual paintings. At the bottom left of the painting are depictions of the donor and his family. Their elaborate dress is typical of West Tibet as known from surviving examples from Tabo Monastery in neighboring Spiti district, also in India.

Black Garuda is a wrathful protector, whom Buddhist practitioners would ask to transmute sickness, harmful spirits, and negative karma by reciting the protective formula written on the back of this thangka. This four-line verse is surrounded by the pacifying mantra, om a hum, repeated seven times. The Black Garuda is depicted here transmuting all negative influences to protect the practitioner or the person for whom the ritual associated with the Garuda is being performed. This painting is an example of a "Black Thangka," which features gold on black paint. Above the Garuda's head is a lama of the Gelug tradition. He is flanked by the Maitreya Buddha and the wrathful protector Vajrapani. The silk frame was already a valuable offering when it was added to the painting at the time it was created. The brocaded silk satin is Chinese and can be attributed to the fifteenth to sixteenth century.

The vast Tibetan plateau, the highest region on Earth, contains two of the world's tallest mountains and is the source of many of the region's major waterways. The vast horizon, the seemingly limitless sky, and the bouts of extreme weather experienced on the plateau have shaped the human and historical geography of the Tibetan cultural zone.

The original religions of this region had complex systems of ritual and prayer dedicated to many spirits and natural phenomena. The Bon religion, one of the oldest indigenous religions in Tibet, is the modern expression of one of these ancient religions. Followers call their religion Eternal Bon (yung drung Bon). According to legend, the religion can be traced to the teacher Tonpa Shenrab, who was thought to have lived in a mythical land to the west of Tibet. The earliest role of the Bon priest was to assure that the spirit of the departed passed safely into the next world.

From the time Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in the seventh century CE, Bon and Buddhism began to influence each other. By the eleventh to twelfth century Bon institutions resembled Buddhist institutions. Bon art is mostly known from recent centuries and has different regional styles, as well as a superficial resemblance to Buddhist art. Bon iconography, never the less, is unique and follows its own canonical sources and ritual practices.

Tibetans also sought to understand their world through scientific inquiry. Their system is adapted from the Indian five categories of knowledge. An important subdivision of this inquiry is divination and astral sciences, which are related to other fields of knowledge in Tibet such as medicine and mathematics. The astrological chart in this section was used for divination. Such inquiries are of great importance in Tibet, with calculations sought at both the highest institutional levels as well as in daily life.

Tucci received this thangka from Namkha Jigme Dorje in Himachal Pradesh, India, during his 1931 expedition. A master of the Dzogchen tradition, Namkha Jigme Dorje had first been educated in the Bon tradition and acquired the painting in West Tibet. Tucci called him "one of the most cultivated men I met in Tibet." The subject of the painting is the Bon Long Life deity Tsewang Rigzin. The image is meant both as a support for meditation and as a votive offering to secure the efficacy of the long-life ritual for the person for whom the ritual is performed.

This work is a representation of an eight-Buddha mandala surrounded by scenes of what appear to be the life of Tonpa Shenrab, the real Buddha of our cosmic age and the founder of Bon. As is evident in this painting, Bon, the indigenous religion of Tibet, adopted and adapted elements associated with Buddhism as this foreign religion spread throughout Tibet.

The diagram shown here is called a sipaho, which generally is used as a charm to protect the worshipper from all negative influences from planets, stars, elements, semi-gods, and demons. The central figure is the cosmic tortoise surrounded by flames. A divination chart of Chinese origin-consisting of the nine numerical squares, the eight trigrams, and the animals of the cycle of twelve years-is painted in the middle of its belly.

Rahu, the subject of this painting, is depicted in his wrathful form as Sachog Gyalpo, the king of the planets whose body is covered with one thousand eyes. The lower part of his body is that of a snake and he stands in a sea of blood. His right hand holds a Makara-banner and his left hand holds a bow made of animal horn and an arrow. His nine heads are crowned by a raven's head.

Major support for this exhibition is provided by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation, John and Fausta Eskenazi, Lisina M. Hoch, and an anonymous donor.

Generous support is provided by Misook Doolittle in honor of Chae Ok Rollison, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky, and Carlton Rochell Asian Art.

Additional support is provided by the Ellen Bayard Weedon Foundation, the Blakemore Foundation, and Trace Foundation.

Asia Society appreciates the support of Susan L. Beningson and Steve Arons, John and Berthe Ford, and James J. Lally.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Global Council on Asian Arts and Culture, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and New York State Council on the Arts.

Buddhism & Beyond is a series of programs exploring Buddhism, its practice, and its popularity in contemporary culture, organized in conjunction with Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting.

KEYNOTE ADDRESS

Keynote Address: Moving Borders: Tibet in Interaction with its Neighbors

Friday, May 4, 2018 • 6:30-8:00 pm

Andrew Quintman, Yale University, gives the Keynote Address to introduce a day-long symposium which will take place at Asia Society on Saturday, May 5. As part of Free Admission Fridays the museum is open from 6:00 to 9:00pm.

SYMPOSIUM

Moving Borders: Tibet in Interaction with its Neighbors

Saturday, May 5, 2018 • 9:30 am-6:00 pm

International scholars, art historians, and curators focus on the moving borders of the Tibetan cultural zone across the centuries, from the Imperial period to the present, including the Western exploration of Tibet.

PAST PROGRAMS

RETROSPECTIVE FILM SERIES

Pema Tseden: Celebrating a Tibetan Voice

January 27-28, 2018

Pema Tseden was born in 1969 in Amdo, in the Tibetan region of Qinghai Province. He is widely recognized as the leading filmmaker of a newly emerging Tibetan cinema and the first director in China to film his movies entirely in the Tibetan language.

DISCUSSION

The Miracle of Mindful Meditation

Thursday, February 15 • 6:30-8:00 pm

ABC news anchor and author of 10% Happier, Dan Harris and leading Buddhist scholar Dr. Thupten Jinpa.

MEMBERS-ONLY OPENING TEA RECEPTION & LECTURE

Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting

Tuesday, February 27 • 4:00-8:00 pm

4:00 pm Tea reception

5:30 pm Docent–led tour

Galleries open until 6:30 pm

6:30 pm Lecture: Walking With Tucci: A Visual History of Tibet

Join art historian and exhibition guest curator Deborah Klimburg–Salter as she introduces the extraordinary group of works from the Museum of Civilisation/Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci," Rome, featured in Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting. Klimburg–Salter was research director for the Guiseppe Tucci Photographic Archive and guest curator for the Tucci collection (MU-CIV / MAO '"Giuseppe Tucci").

All programs are subject to change. For tickets and the most up-to-date schedule information, visit AsiaSociety.org/NYC or call the box office at 212-517-ASIA (2742) Monday through Friday, 1:00-5:00 pm.

VIDEOS

NEW YORK, February 20, 2017 — 'Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting' is the first-ever U.S. showing of the paintings collected by Italian scholar Giuseppe Tucci during his 1926-1948 expeditions to Tibet. The recently restored paintings are on loan from the collection of the National Museum of the Oriental Art (MNAO), Rome, and span the 13th through 19th centuries. They are presented together with photography taken during Tucci's eight major expeditions. (34 sec.)

NEW YORK, April 17, 2017 — Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art at Asia Society Museum in New York, provides an inside look at the Tibetan thangka paintings on display in the exhibition she co-curated, Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Panting. (4 min., 57 sec.)

ARTICLES

'Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddhist Painting' Opens to American Audiences for First Time

Asia Society Museum's highly anticipated exhibition explores Tibet through the eyes of Italian explorer Giuseppe Tucci.

A Guide to Decoding Buddhist Symbolism in Tibetan Art

Understand the significance of specific Buddhist symbols frequently found in Tibetan art.