Book Excerpt: 'Shanghai Gone' Depicts a City Consuming Its Own Past and People

"Shanghai Gone" (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013) by Qin Shao (R).

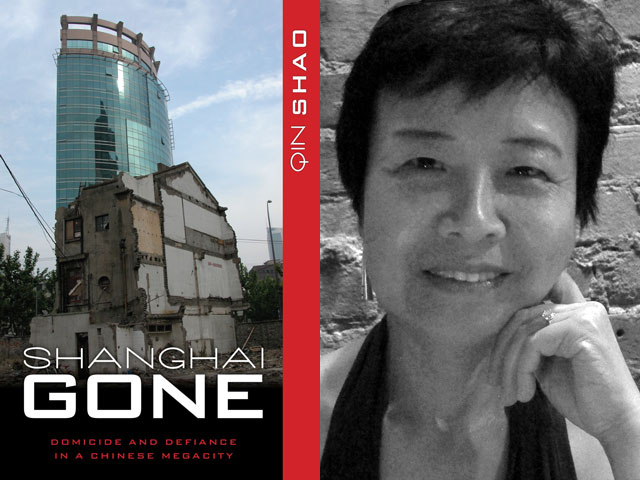

Qin Shao's Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013) bills itself as "the first book to apply the concept of 'domicide' — the eradication of a home against the will of its dwellers — to the sweeping destruction of neighborhoods, families, and life patterns to make way for the new Shanghai."

Shao is currently a fellow-in-residence at Humboldt University, Berlin and professor of history at The College of New Jersey. She has published on topics that include ancient Chinese statecraft, China's early modernization effort, and post-Mao reforms. She is the author of Culturing Modernity: The Nantong Model, 1890-1930 (Stanford University Press, 2004) and her research has led to fellowships from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard University; the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington D.C; the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The following excerpt from Shanghai Gone, "Xintiandi," is a specific case that lays out the human costs of Shanghai's, and by extension China's, frantic rush to development.

"You Destroyed My Home and You Now Own Me"

On a 2005 trip to a Forbes conference in Sydney, Vincent Lo spoke about his development in the Xintiandi area and gave an example about the patience required in doing business in China. Lo's example, according to the reporter, was about "the only [one] family still living on the site and refusing to move unless they are paid $4 million for the relocation. The issue has been going for the last two years and still hasn't been [re]solved." The reporter told the "one funny thing" Lo saw in this case, "That the very family [that] remains on the site doesn't actually have any title to the land they are living on; the local government doesn't want to vacate them because they want to have a 'harmonious' social environment and would never seek violence."

Vincent Lo could qualify as the best spokesman for Chinese government's commitment to a "harmonious society." In reality, however, building such an ideal society is far less important to the Chinese government than building a profitable seven-star hotel complex. The only truth in Lo's statement is that the family in question had indeed been holding out and their house was indeed the last one still standing by late 2005. But the rest of what he said is false — the family did have title to their property; they looked for a reasonable settlement without asking anything remotely close to $4 million; and finally, the government in Shanghai and elsewhere routinely drove residents out of their homes with force and, in this case, evicted the family by kidnapping its matriarch and her daughter in their sleep and then carried out domicide.

The matriarch of the family in question is named Zhu Guangze (1922-), who was in her eighties then. Their three-story unit was located on Lot 108, on Taichang Road, between Xintiandi and Huaihai Zhong Road. It was bought in 1925 by Zhu Guangze's father, who built a thriving paper business in Shanghai. The unit, independent from the neighboring alleyway housing, was what Shanghainese called Western-style garden houses, complete with multiple bathrooms, living rooms, bedrooms, balconies, courtyards, a garden, maids' quarter, and a garage. Lot 108 was to be the site of a seven-star hotel complex, which required the leveling of the entire neighborhood there…

The Zhu family had deep roots in the GMD government. Zhu Guangze's husband was a special commissioner in the GMD's Ministry of Finance. In 1946 he was appointed head of a tax department in a Shanghai district. His various diplomas and appointment letters were signed by Chiang Kai-shek, H. H. Kung (Kong Xiangxi), Chiang's minister of finance, and Wu Guozhen, Shanghai's mayor in the late 1940s. His brother-in-law, Zhou Hongtao, was once Chiang Kai-shek's secretary. Zhu Guangze herself graduated from St. John's University in the mid-1940s.

In 2002 when the Wuxin Co. (Luwan District's demolition company) started the demolition on Lot 108, Zhu Guangze — her husband had died years earlier — lived together with her daughter and son, both married and each with a child. The three-year struggle from 2002 to 2005 over their relocation could have been much less traumatic if the district had accommodated their initial request. The question, as in many other cases, was where and how.

Zhu Guangze asked for three apartments within Luwan District, one for herself, the other two for her daughter and son respectively. The district rejected the request and instead, following its usual practice, assigned them to apartments in the suburbs. The family then was willing to accept a cash settlement so that they could purchase a house nearby. The district employed a number of schemes to drive down the value of their house, which led to a series of conflicts. First, the district tried to deny that the Zhus owned the house, a fabrication that Vincent Lo continued to perpetrate in 2005. Then the district considered the Zhu house as a new-style alleyway type instead of an independent house — the government assigned a different amount of compensation for the two types of housing, with the latter being of higher value. In addition, it insisted the house was smaller than the Zhus had claimed, yet refused the family's request to actually measure the house. Finally, although Zhu and her daughter and son lived together, they were in fact three families — Zhu Guangze herself, her daughter and her family, and her son and his family — each of which had its own, separate household registration. This was an important detail in the calculation of the compensation because, according to relevant regulations, each family was entitled to an independent settlement. But the district tried to shove Zhu's children, especially her daughter, aside and focused its attention on Zhu Guangze who, in her advanced age, was considered the weakest link.

The district almost succeeded. At midnight one night in June 2003, the district demolition office, after exerting much pressure, compelled an exhausted Zhu to sign a contract for a cash settlement. But the contract offered little for Zhu's daughter, who naturally protested. She was nevetheless willing to compromise if only the district would add 30,000 yuan to the package, which would allow her to purchase her own apartment. The demolition office, with Zhu's signature in hand, refused her daughter's request, losing a rare opportunity to settle the matter.

Under pressure from the family and frustrated with the district, Zhu declared that she was rescinding the contract, for which the district demolition office took her to court, causing even more bad blood with the family. The case stalled, and the swelling real estate market over the next two years only further diminished the possibility of reaching a settlement. In fact, the rising market had made the amount of compensation a moving target. Initially, the district offered about 4,600 yuan per square meter, not enough for the Zhus to purchase a comparable home downtown. By 2005, with the rapid rise in the market, the district agreed to pay 10,000 yuan per square meter, but the family wanted 50,000 yuan, the current market price so that they could afford to buy their own apartments. The district refused to bridge the gap of 40,000 yuan.

Instead the district kept the pressure on. Throughout the three years of contention, the district issued three administrative rulings, each with a deadline for the family to get out. The district court subpoenaed Zhu twice for revoking the contract. The Wuxin Co. demolition squad also employed what the family claimed was a series of "abnormal, despicable, mean and dirty tricks," to "torture" them and "threatened" their "property rights and personal safety." The team stole their iron doors in the front and broke their windows. When the family called the emergency number for help, the police told them to "just move out." The Wuxin Co. also destroyed the sewer system and gas supply to the house. The family resorted to using a chamber pot. The demolition squad tried to set fire to their roof, a known scheme employed by local governments in Shanghai and elsewhere to force residents out. It also used another common "dirty trick," literally — for a period of time the demolition squad sent its members daily to use the Zhu's courtyard, which was exposed after the front doors were stolen, as a toilet…It became a nerve-racking, full-time job for the family to struggle with and document all these abuses.

The climax of this sustained harassment came in the morning of November 18, 2005. By then, the construction of the hotel complex on Lot 108 had already started but could not go full speed with Zhus' house in the way. The district lost patience. The last round of threats came on October 25, 2005, when the district issued yet another eviction notice, this time ordering the family to move out within fifteen days. Yet the district did not carry out the eviction on the designated date. The family interpreted that to mean the deadline was yet another empty threat. But suddenly on the morning of November 18 after most of the family members had gone to work, dozens of men from the Wuxin Co. broke into the Zhus' house. They first got hold of Zhu's daughter, who screamed "help" to warn her mother, who was still asleep in her bedroom on the third floor. The demolition squad threw both of them into a parked van and drove them away. Within hours, the Zhus' house became another victim of domicide — it was knocked down and reduced to a pile of debris.

Zhu Guangze recounted the "barbaric kidnapping and eviction" of her and her daughter that morning:

A group of frightening scoundrels broke into my house. Without showing any identification cards, they rushed into my bedroom, tied my hands, and rolled me up in my blanket. I tried to resist but I could hardly move. They dragged me down from the third floor and, in the struggle, I suffered multiple bruises. When they brought me out to the van, I tried to scream "help" in English because there are often foreigners around Huaihai Road, but my voice was too weak to be heard. They then drove my daughter and me to a basement and locked us up. I realized that I'd been kidnapped and was now homeless. "How am I going to live like this? Why am I still alive?" I asked myself. I took off my gold ring and swallowed it; I no longer wanted to live.

Zhu's life was spared that day because a guard saw her desperately swallowing something and took her to the hospital. She was so traumatized by the violence that she lost sight in her left eye overnight and was hospitalized for a week. But her life as a homeless person and her family's anguish over the eviction had only just begun. That afternoon on November 18, when Zhang Xiaoqiu, Zhu's daughter-in-law, returned home, she witnessed the site of domicide: the house was gone, and so were her mother-in-law and sister-in-law. She cried and collapsed to the ground, which was littered with broken but still familiar pieces of her home-no-more: caved stairway rails, stained window glass, and a French bathtub for which an antique dealer had once offered 10,000 yuan. She contacted her husband and son. They frantically went out to search for their missing family members, only to learn that their mother had tried to commit suicide.

Zhu Guangze's daughter and son have since found their own apartments, but not Zhu Guangze herself. She was so deeply offended by the domicide that she was willing to use herself as leverage to compel the district to solve the conflict. She refused to move in with her son and insisted on staying in the basement to which she had been brought on the day of kidnapping. She told the demolition team, "You destroyed my home and you now own me. You are responsible for taking care of me." …The district arranged for Zhu to stay in a small, temporary apartment with a maid about an hour's bicycle ride away from her son's new home. Her son, whom the district has accused of being unfilial, visits her daily. In early April 2007, Zhu Guangze fell down in the apartment and broke her hip. When I visited her in July, she had been confined to bed for three months and had not been able to take a bath. No more than 70 pounds and suffering from heart diseases, her body seemed to have disappeared under the blanket. But she had no intention of ending her self-imposed bondage. She talked to me for an hour about her ordeal and her resolve, pledging her life to "seek justice according to the law: return my home and compensate me for the damage to my family."

Like others who have suffered from domicide, Zhu Guangze and her family simply cannot accept that their loss, so unjust, will be permanent; they want someone to take responsibility and have been petitioning since.

Excerpted from Shanghai Gone by Qin Shao. © Qin Shao/Rowan & Littlefield.