- Overview

- Trade Routes in Ninth-Century Asia

- The Discovery

- The Controversy Surrounding the Recovery

- The Crew: Life on Board

- The Cargo: Storage Jars

- The Cargo: Xing Ware

- The Cargo: Yue Ware

- The Cargo: Gongxian Ware

- The Cargo: Blue-and-White Ceramics from the Gongxian Kilns

- The Cargo: Changsha Ware

- The Cargo: Gold and Silver

- The Cargo: Mirrors

- Global Trade at the Time of the Belitung Shipwreck and Beyond

- The Ship

- Related Programs & Events

- Credits

- Overview

- Trade Routes in Ninth-Century Asia

- The Discovery

- The Controversy Surrounding the Recovery

- The Crew: Life on Board

- The Cargo: Storage Jars

- The Cargo: Xing Ware

- The Cargo: Yue Ware

- The Cargo: Gongxian Ware

- The Cargo: Blue-and-White Ceramics from the Gongxian Kilns

- The Cargo: Changsha Ware

- The Cargo: Gold and Silver

- The Cargo: Mirrors

- Global Trade at the Time of the Belitung Shipwreck and Beyond

- The Ship

- Related Programs & Events

- Credits

"Astonishing"

"Full of lessons big and small"

In 1998, Indonesian fishermen diving for sea cucumbers discovered a shipwreck off Belitung Island in the Java Sea. The ship was a West Asian vessel constructed from planks sewn together with rope — and its remarkable cargo originally included around 70,000 ceramics produced in China, as well as luxurious objects of gold and silver. The discovery of the shipwreck and its cargo confirmed what some previously had only suspected: overland routes were not the only frequently exploited trade connections between East and West in the ninth century. Whether the vessel sank because of a storm or other factors as it traversed the heart of the global trading network remains unknown. Bound for present-day Iran and Iraq, it is the earliest ship found in Southeast Asia thus far and provides proof of active maritime trade in the ninth century among China, Southeast Asia, and West Asia.

The objects in this exhibition attest to the exchange of goods and ideas more than one thousand years ago when Asia was dominated by two great powers: China under the Tang dynasty and the Abbasid Caliphate in West Asia. Specifically, the cargo includes some objects of great value and beauty, and demonstrates the strong commercial links between these two powers, as well as the ingenuity of artists and merchants of the period. Moreover, the sheer scale of the cargo shows that in the ninth century Chinese ceramics were greatly popular in foreign lands and that Chinese potters mass-produced thousands of nearly identical ceramics for foreign markets. Ceramics found in the wreck range from humble Changsha wares to those that reflect elite taste such as celadon ware from Yue kilns and white ware from Xing kilns that were valued for their beauty and elegance.

In the past the common historical narrative described major global maritime networks connecting Asia to the rest of the world first emerging in the fifteenth century as western explorers and adventurers asserted a role in the region. With the discovery of the shipwreck near Belitung we now know that important, complex, and dynamic networks of maritime trade already connected disparate cultures across the globe as early as the ninth century.

Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia is co-organized by Asia Society and the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Objects are from the Khoo Teck Puat Gallery, Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. The Tang Shipwreck Collection was made possible by the generous donation of the Estate of Khoo Teck Puat in honor of the Late Khoo Teck Puat.

Asia Society Executive Vice President Tom Nagorski discusses Secrets of the Sea with Museum Director and Vice President for Arts & Cultural Programs Boon Hui Tan

Ninth-century Asia was dominated by two great powers: China under the Tang dynasty and the Abbasid Caliphate in West Asia with its capital at Baghdad in modern Iraq. The Southeast Asian kingdom of Srivijaya—which dominated the sea routes through Sumatra, Java, and the Malay Peninsula—lay at the critical connection between East and West. These distinctive and far-flung lands were joined through overland and maritime trade.

The overland Silk Route that connected China with Central Asia and West Asia during the Tang period is well known, but only now are we beginning to understand the full importance of the maritime trade routes that also linked these regions. Compared to the long overland journey on camels or horses, maritime transport meant that fragile, but heavy loads could be exported in bulk—in the case of this one shipwreck that meant over twenty-five tons of ceramics—from China to West Asia. The use of maritime routes became even more popular during the Tang dynasty when the Arab conquest in the west and civil war in China made overland travel increasingly dangerous and resulted in its diminishing use through the eighth century.

The discovery of the shipwreck confirms that sea routes had become a lucrative alternative route for trade by the ninth century. To reach the coast, the contents of this particular vessel had already traveled through an internal shipping network along rivers and canals that gathered a range of products, including ceramics, gold and silver works, and bronze mirrors, from all over China at one or two ports, probably the major port of Yangzhou or further south at Guangzhou. When it sank off Belitung Island, the West Asian ship appears to have been heading south, possibly to trade for valuable spices like nutmeg and clove with the Southeast Asian empires of Srivijaya and Sailendra, prior to sailing homeward with objects, spices, and other goods from China and Southeast Asia. The ship had likely carried glass, spices, and minerals to China, where they were traded for silk, ceramics, and lead (which may have on-loaded in China as ballast). India and Southeast Asia contributed goods and crewmen to this network of trade.

In 1998 fishermen diving near Belitung Island saw an unusual mound about three feet high rising from the sea floor. Upon further exploration they discovered the mound was composed of coral-encrusted ceramic bowls, many of which were still intact. The discovery of these bowls and the rest of the nearby shipwreck soon came to the attention of Indonesian government authorities. As it turned out, the unique construction of the sunken ship was unlike locally built vessels. Each of the ship’s timbers was fastened with stitching—not nails or other iron fastenings, or even wooden dowels. Archaeological research revealed that the ship is West Asian in origin and that its keel (the chief structural element that extends downward from the center of the ship’s bottom) measures more than fifty-feet long. The vessel had been constructed with wood from Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, and Arabia in a technique that still survives in the ancient ship-building tradition of Oman. Many of the ceramics onboard were perfectly preserved, neatly packed and protected by the silty floor of the sea. As the cargo and vessel were closely examined, the importance of the discovery and recovery became even clearer: it was the first wreck of an ancient Middle-Eastern ship to be found and excavated.

The ship was carrying a small amount of cash in the form of Chinese bronze coins (seen here) and large silver ingots. The presence of the coins on the ship suggests some of the earliest evidence of their acceptability in Southeast Asian markets. (Photography by Michael Flecker, 1999)

The wreck discovered by the fishermen lay in shallow water less than two miles from Belitung Island, making it vulnerable to looting and accidental destruction from fishing. Reports of looting emerged early on and the Indonesian government—its resources simultaneously focused on economic troubles and quelling related racial riots—authorized a salvage company, Seabed Explorations, to recover the cargo. Over the course of two seasons in 1998 and 1999 the company retrieved some 60,000 objects.

Some have argued that commercial salvage as deployed for this site was not the most appropriate way to recover the ship and cargo. If an academic underwater archaeological excavation had been conducted there would have been more documentation, but this also would have required significantly more time and financial resources. The Indonesian Government settled on a quicker and completely legal process that made it possible for them to move recovered objects to conservation and storage facilities. The cargo was preserved largely intact from looting and at the same time valuable information was recorded.

This exhibition and its related programming provide an opportunity to discuss underwater cultural heritage and the complex questions surrounding archaeology, preservation, commercial salvaging, looting, and international law. The recovery and sale of the cargo by Seabed Explorations were commercial transactions, which is problematic. The wreck, however, is one of the most important discoveries from the last fifty years and it is important that we share this historic story of global interaction.

Changsha bowls from the wreck tightly packed inside a storage jar. (Photography by Michael Flecker, 1999)

The recovery of the ninth-century wreck yielded no human remains nor records indicating who manned the ship. It can be assumed that traders from West Asia probably chartered the ship, and that it is likely there were at least a few Chinese crew on board. The ports throughout Asia in the ninth century were cosmopolitan hubs. The populations of the Chinese trading ports at Ningbo, Guangzhou, and Yangzhou included Arabs, Chams (from central Vietnam), Indians, Malays, and non-Muslim Persians. Nearly all the space on the ship, including below deck, was given over to stowing the cargo, meaning that the crew would have suffered a great deal of exposure as they led their lives on deck. These conditions combined with the other hazards of the journey meant that some of the crew very likely died along the way and new men would have been recruited at ports where the ship stopped.

Objects recovered from the wreck support the theory that the ship’s crew was multi-ethnic. Tools used for everyday ship maintenance and personal possessions originating from across Asia were found with the wreck. They include weights and a scale bar of the kind used in Indonesia; a Chinese inkstone for grinding ink; and bronze spoons, ceramic lanterns, kettles, a mortar and pestle, a grindstone, and roller of the kind used in Southeast Asia. Lead weights of unknown origin used as sinkers for fishing nets, a Chinese needle for mending sails, and ivory game pieces of unknown origin were also recovered.

The crew had to combine ballast with the cargo to keep the ship stable in the water. If the ship sat too high in the water, it would be in danger of capsizing; too low and it could be swamped by waves. The crew adjusted the ballast at every port of call as cargo was loaded on and off. There were lead bars found in the wreck that it is assumed were used as ballast. Despite the skill of its crew and having sailed thousands of miles, the ship never reached its final destination. It is unclear what caused the ultimate demise of ship and man. It is likely to have been the result of a storm, a crash into a reef near where the wreckage was found, or a combination of the two.

A diver for Seabed Explorations GBR with a storage jar from the wreck during the excavation and recovery. (Photography by Michael Flecker, 1999)

The wreck contained many storage jars made in Guangdong Province in southern China. Storage jars with a wider opening held as many as 130 Changsha ceramic bowls tightly stacked in coils inside and padded with straw. Thanks to this space-saving packing method, as well as the silt of the seabed, many of the bowls were able to survive intact for over 1100 years. Jars also served other functions: one was filled with nine lead ingots, while several were found full of star anise, a fragrant spice from China.

After centuries underwater, many of the jars became encrusted with coral. Others were restored to their original state, but only through many hours of painstaking work by conservators. Once cleaned some jars were found to bear inscriptions. These may be merchant’s marks.

Chinese white wares were immensely desirable, both within China and abroad. By the latter part of the Tang dynasty Xing ware was frequently extolled in Chinese poetry and literature for its beauty and used as a symbol for taste and wealth. Its appearance was likened to that of silver. Xing ware has been discovered throughout Southeast Asia and West Asia and it was likely considered among the most valuable cargo onboard the ship. The three hundred white ceramics found in the shipwreck are of high quality and were probably very expensive even in the ninth century. The Xing kilns in Hebei Province in northern China produced the most sought-after Chinese white wares. The wares are thinly potted, trimmed into precise shapes, and evenly covered with a fine white glaze that, once fired at high temperatures, gives the ware a pure white body. In West Asia, Abbasid caliph courtiers were so entranced by this durable, white ware that potters from Basra strove to duplicate them using the local yellowish clay and an opaque white glaze.

Yue ware is gray-bodied and covered with olive-green glaze, the appearance of which was likened to jade. The production of this kind of ceramic dates back as far as the fourth-century BCE. During the Tang period, when the shipwreck pieces were made, a group of kilns in Zhejiang Province produced them. Yue wares were held in high esteem both domestically, where the finest pieces were offered as tribute to the court, and abroad. Around two hundred Yue wares were recovered from the shipwreck. By the latter part of the Tang dynasty, Yue ware was frequently praised in Chinese literature for its beauty and used as a symbol of taste and wealth, much like Xing ware, some of which the ship also carried. For the world outside China the aesthetics of the high-fired clay and glaze were highly appealing as was its comparative resilience that made it more difficult to chip and crack than local products. Yue wares have been found in Southeast Asia, Japan, Iraq, Iran, and even Egypt.

The Gongxian kilns of inland China were noted for their production of tomb wares, but in the ninth century in response to the burgeoning trade of China’s south and southeastern ports, they created colorful daily-use wares for export. The bodies of these wares were covered with a white coating of slip and over this both copper and cobalt were used as coloring agents in glazes. The bright green seen on the Gongxian objects is the result of copper while the rich blue on the dish comes from cobalt.

The approximately two hundred pieces of green-splashed white wares discovered with the shipwreck represent the largest cache of this type of ware recorded to date. The pieces were located at the ship’s stern along with the other items of higher value. The desirability of these ceramics in the Abbasid Caliphate (covering what today includes Iran, Iraq, and surrounding regions) is supported by many finds in West Asia, including in Samarra, Iraq, the former capital of the Abbasids, where an example of Gongxian ware decorated with a lozenge with vegetal palmette projections was found.

Long-necked ewer. China, probably Henan Province. Gongxian kilns. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–50. Glazed stoneware with copper-green splashes over white slip. H. 40 1/2 x W. 9 x D. 10 1/4 in. (102 x 23 x 26 cm). Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00900 1/2 to 2/2. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Tang Shipwreck Collection

This large ewer is one of the finest ceramics found in the shipwreck. The incised lozenge motifs with leafy fronds is an Iranian design seen on other objects in the wreck, which suggest that much of the cargo was destined for the Persian Gulf. The overall form of the ewer is based on that of objects produced in metal, as is evident from the rim surrounding the base, and the thinness of the handle. The ewer is difficult to hold and balance, and may have been made purely for decoration. The stopper, shaped like a dragon’s head, roughly fits the mouth of this ewer, but may have belonged to another vessel.

Four-lobed bowl with dragon medallion. China, probably Henan Province, Gongxian kilns. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–850. Stoneware with pale copper-green glaze over white slip. H. 5 x D. 14.5 in. (12.7 x 36.8 cm). Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00396. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Courtesy of John Tsantes and Robert Harrell

Potters in both China and West Asia contributed to the ninth-century creation of the earliest known blue-and-white ceramics. The blue of blue-and-white ceramics is created with cobalt, which was a specialty of Iran. Painting with cobalt blue was a practice that appears to have started with Basran potters. However, it was China that had the natural resources to exploit to create attractive, hard white ceramics. The potters of the Gongxian kilns were able to take the Iranian method of painting with cobalt blue on ceramics and apply it to their own ceramic output. Three blue-and-white dishes retrieved from the shipwreck suggest that Gongxian potters combined cobalt blue with white ceramics in an effort to cater to the demands of the Abbasid Empire (covering what today includes Iran, Iraq, and surrounding regions).

The Gongxian potters painted a lozenge pattern with flowers at the corners on one object included in th exhibition. This design appears on a variety of objects bound for the Abbasid, where the design originally developed. The blue-and-white dishes discovered with the ship are the first and earliest complete Chinese blue-and-white ceramics known to exist to date.

Dish with floral lozenge decoration. China, Henan Province. Gongxian kilns. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–50. Glazed stoneware with cobalt-blue pigment over white slip. Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00473. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Courtesy of John Tsantes and Robert Harrell

.jpg)

Changsha ewers trapped in a coral concretion on the top of the wreck mound. (Photography by Michael Flecker, 1999)

The Changsha kilns operated in the central southern Chinese province of Hunan, outside China’s centers of commerce. Changsha wares were popular in both domestic Chinese and foreign markets. Changsha bowls of the type in the cargo have been found on Java and throughout Southeast Asia, which confirms that Chinese ceramics were traded in the region in the ninth century. It is likely that the ship was headed to Java to trade for valuable spices such as nutmeg and clove. A Changsha bowl, from among the 55,000 recovered from the shipwreck, helped date the entire group through its inscription. The bowl has the Chinese date that is equivalent to 826, the last year of the reign of Tang Emperor Gaozu, inscribed into the clay.

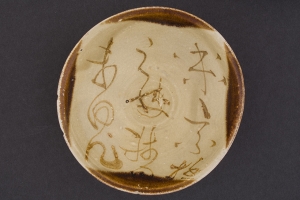

Changsha wares were painted with brown, green, and red iron- and copper-oxide-based pigments. The patterns were hand painted and surprisingly varied. The majority are designs based on forms from nature like flowers, leaves, mountains, clouds, or birds. Imagery with ties to the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, like hybrid sea creatures known as makara, also appear on the bowls. Several examples recovered from the wreck feature calligraphy, often in the form of a poem. Molded decoration of date palms, birds, or lions were also used to further embellish some vessels, as is the case with the ewers on view, which were some of the most popular products from the Changsha kilns.

.jpg)

Stacks of Changsha bowls deep within the wreck mound. (Photography by Michael Flecker, 1999)

Bowl with decorative inscription in cursive script. China, Hunan Province. Changsha kilns. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–50. Glazed stoneware with underglaze iron-brown. H. 2 x W. 6 in. (5.1 x 15.2 cm). Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00580. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Courtesy of John Tsantes and Robert Harrell

The style of cursive calligraphy on this bowl is reminiscent of the great Tang-dynasty calligrapher Huaisu (737–after 798), a famed Changsha resident. His wild cursive style is said to be due in part to the influence of wine. The presence of Huaisu-style calligraphy on this bowl attests to the pride with which Changsha residents regarded his brushwork.

A round, silver box containing a set of small, lobed, silver-gilt boxes recovered from the wreck. (Photography by Michael Flecker, 1999)

More than thirty gold and silver objects created in Tang China were recovered from the Belitung shipwreck. Their location when discovered suggests that they had been concealed in the hold of the vessel. The presence of these was a great surprise to scholars and their discovery ranks among the most important Tang gold and silver finds to date.

The group includes beautifully ornamented vessels for entertaining, including cups and dishes made of solid gold, a wine flask of gilt silver, and silver bowls and platters. The cargo also included fourteen silver boxes for holding cosmetics, incense, and medicines. Whether these rare, valuable goods were bound for use in diplomatic exchange, entertaining high-ranking visitors to the recently docked ship, trade negotiations, or sale to wealthy elites is unknown. It is likely that the objects were manufactured in a workshop located in the east coast Tang Chinese craft centers of Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, or Shaoxing. In addition to these extraordinary objects, eighteen silver ingots and gold foil were also found with the wreck.

Square-lobed dish with insects, flowers, knotted ribbons, and swastika (wan, “10,000”). China. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–50. Gold. H. 1 1/4 x W. 6 x D. 4 in. (3.5 x 15.5 x 10 cm). Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00922. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Tang Shipwreck Collection

The swastika, an image that was transmitted to China with Buddhism via India, is read wan in Chinese and means “10,000.”

Four-lobed oval box with deer and lion decoration. China. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–50. Silver, parcel-gilt. H. 1 x W. 3 1/2 x D. 2 1/2 in. (2.5 x 8.9 x 6.4 cm). Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00865 1/2 to 2/2. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Tang Shipwreck Collection

Fan-shaped box with parrot and duck decoration. China. Tang dynasty, ca. 825–50. Silver, parcel-gilt. H. 1 x W. 3 1/2 x D. 2 1/2 in. (2.5 x 8.9 x 6.4 cm). Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2005.1.00868 1/2 to 2/2. Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum, Tang Shipwreck Collection

Chinese mirrors were generally cast of a copper alloy with enough tin to create a silvery color. One side is often elaborately decorative while the other is smooth and highly polished to create a reflective surface. The examplles found with the wreck are blackened from centuries under water. There were twenty-nine Chinese mirrors discovered in the shipwreck, most likely for trade rather than personal use by the crew. The majority of the mirrors are decorated with popular Tang Chinese patterns of lions, grapevines, and flying birds.

The Jewel of Muscat, a ship constructed based on the Belitung wreck and evidence of early West Asian shipbuilding, during sea trials off Oman. (Photography by Michael Flecker)

It is likely that the ship carrying the objects set sail from West Asia during the height of ninth-century maritime trade activity with China and Southeast Asia. This especially active period began around 829, when a Chinese edict granted imperial protection to foreign merchants operating in Guangdong, Fujian, and Yangzhou, and lasted to 879, the year Guangdong was sacked and large numbers of foreign merchants were killed by rebel leader and wealthy salt merchant Huang Chao and his followers.

China’s sea trade again became vigorous during the Song dynasty (960–1279) when ships began carrying Chinese goods from ports in East Asia to east Africa. The Chinese government also sent missions to Southeast Asia to encourage trading and Chinese ships began to challenge the prowess formally held by Indian and Arab merchant ships.

A new pattern of maritime trade emerged in the fourteenth century as Asia, Europe, and parts of Africa became more closely linked and long voyages were replaced by shorter journeys. The Malays, Javanese, and other peoples of Southeast Asia were especially active in interregional trade during this time. Melaka, on the Malay Peninsula, became the southeastern terminus for the great Indian Ocean maritime trading network and is said to have been the most active port in the world with a free trade policy and 15,000 merchants.

Beginning in the fifteenth century Europeans started to assert a role in the region, starting with the Portuguese explorers and adventurers. The Portuguese conquered Melaka in 1511, followed by the Spice Islands of Eastern Indonesia a few years later. Over the next several centuries the Spanish, the Dutch, the English, the French, and finally North Americans came to play major roles in Asian maritime trade.

Forefoot of Jewel of Muscat showing sewn planks. (Photography by Alessandro Ghidoni, 2009)

The objects in Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia were once part of the cargo on a ninth-century wooden vessel. The discovery of this wreck gave us the first Maritime Silk Route trading ship constructed to ply the waters from West Asia to East Asia that we have been able to study. Parts of the stem, keel, keelson, floors, frames, beams, beam shelf, and a significant portion of planking survived the ravages of the ocean and time.

The Jewel of Muscat was a vessel based on the remains of the Belitung wreck. From the wreck, specialists could see that the planks of the ship were stitched together with rope, a technique that originated in the Arab world and still survives in Oman today. In the case of sewn-plank vessels, the shell of the hull is assembled first and then the framing is fitted, because it is not possible to sew planks where frames are in the way. To assure that the boat is water-tight, each plank has to be perfectly fitted to the next.

Sewing the stem to the forward end of the keel on Jewel of Muscat. (Photography by Alessandro Ghidoni, 2008)

Fitting Jewel of Muscat frames inside the shell of the hull. (Photography by Alessandro Ghidoni, 2009)

Jewel of Muscat just before launching in the Gulf of Oman. (Photography by Alessandro Ghidoni, 2009)

LECTURE

Green, Blue, and White: The Tang Shipwreck Ceramic and Precious Metal Cargo and Global Trade in Medieval Asia

Monday, May 2• 6:30 pm

Scholar and curator John Guy explores the unique insights that shipwreck archaeology can bring to our understanding of historical trade and exchange.

SPECIAL EVENT

The Tang Dynasty Ball

Thursday, April 27

Please join us for a reception featuring live musical entertainment, fusion cuisine, dinner, and dancing.

PERFORMANCE

Soul Journey: Traditional Nanyin Music Reimagined

Wednesday, April 26 & Friday, April 28

Singapore’s Siong Leng Musical Association was founded in 1941 to promote and preserve traditional Nanyin music and Liyuan Opera.

EXHIBITION SYMPOSIUM

Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia

Keynote Address, Friday, April 21

Co-organized by Asia Society and the Tang Center for Early China at Columbia University.

MEMBERS-ONLY LECTURE

Connecting Empires: Shipwrecks, Ceramics, and Maritime Trade in Ninth-Century Asia

Tuesday, March 7 • 6:30 pm

Join Stephen A. Murphy for an in-depth perspective on the groundbreaking exhibition Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Dynasty Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia. Murphy is curator for Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, and curator-in-charge for the Tang Shipwreck Gallery.

All programs are subject to change. For tickets and the most up-to-date schedule information, visit AsiaSociety.org/NYC or call the box office at 212-517-ASIA (2742) Monday through Friday, 1:00-5:00 pm.

Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia is co-organized by Asia Society and the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Objects are from the Khoo Teck Puat Gallery, Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. The Tang Shipwreck Collection was made possible by the generous donation of the Estate of Khoo Teck Puat in honor of the Late Khoo Teck Puat.

.png)

The exhibition is made possible by the generous support of Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang, Ph.D.

Major support for this exhibition is provided by the Mary Griggs Burke Fund; the Singapore Tourism Board; the National Heritage Board, Singapore; and Lisina M. Hoch.

Additional support is provided by ICBC (Industrial & Commercial Bank of China).

Exhibition opening and lifestyle programming

Presented by In association with

.png)

.png)