Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity

This exhibition presents 19 artworks by seven artists, born in mainland China in the 1980s. Belonging to what is referred to as the ba ling hou generation, they grew up in a post-Mao China shaped by the one-child policy and the influx of foreign investment. Comprising painting, sculpture, performance, installation, video, digital art, and photography, the exhibition reflects the dramatic economic, political, and cultural shifts the artists have experienced in China during their lifetimes.

The exhibition’s title, Mirror Image, refers to the double reflection at the heart of the exhibition. Rather than emphasizing their “Chinese-ness,” these artists’ respective practices are born of a contemporary China where Starbucks can be found in the Forbidden City and the internet permits them access—despite the obstacles of censorship—to a host of influences beyond geographical boundaries.

Organized by Barbara Pollack, guest curator, with Hongzheng Han, guest curatorial assistant.

Participating Artists

Tianzhuo Chen (Born 1985 in Beijing, China; lives and works in Beijing)

Cui Jie (Born 1983 in Shanghai, China; lives and works in Shanghai)

Pixy Liao (Born 1979 in Shanghai, China; lives and works in Brooklyn, New York)

Liu Shiyuan (Born 1985 in Beijing, China; lives and works in Beijing and Copenhagen, Denmark)

Miao Ying (Born 1985 in Shanghai, China; lives and works in Shanghai and New York City)

Nabuqi (Born 1984 in Inner Mongolia, China; lives and works in Beijing, China)

Tao Hui (Born 1987 in Chongqing, China; lives and works in Beijing, China)

Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity poses the question “What remains of ‘Chinese-ness’ once China has become a fully globalized nation?” Through the artworks of seven artists—all born after 1976 (the year of Mao Zedong’s death), all products of the one-child policy, and all having come of age in an emerging superpower, this exhibition posits that a new transnational sense of self has emerged. Barely considering the traditional East-West dichotomy that dominates discussions of older generations of Chinese artists, these younger artists are full-fledged participants of a global art world.

The title, Mirror Image, refers to the double reflection at the heart of this exhibition. The participants in this exhibition reject the nationalistic label of “Chinese artist” and prefer the banner “global artist.” Eschewing stereotypical iconography and self-Orientalizing, these artists create works that reflect a contemporary China, where Starbucks can be found in the Forbidden City and the internet permits access—albeit with the help of a VPN—to countless sources of influence beyond geographic boundaries. At the same time, as they examine themselves looking inward, they anticipate the reception of a global audience and challenge distortions of identity that assume Chinese artists are exotic, isolated, or politically motivated. Like a hall of mirrors, there is no one way to interpret their work and no single way of seeing things.

The work of this circumscribed group of artists—the 1980s generation, or ba ling hou—represents the prime examples of the impact of globalization on art production in China. They grew up during the first wave of economic transformation set into motion by Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door policy (initiated in 1978) and became artists in a milieu that has benefited from the expansion of the domestic art infrastructure in the early 2000s. Such rapid development—reflected in the innovations in the works in the exhibition—may be the most quintessentially Chinese in the artistic output of their generation. No need to search for Ming Dynasty furniture or references to the Cultural Revolution. From TikTok soap operas to a digital media project run by artificial intelligence to simulate China’s social credit plan, these artworks reveal the outlook of a generation of artists who view themselves as citizens of the world rather than ambassadors of a foreign country.

With the rules of quarantine set in response to the pandemic and with the rise of Xi Jinping and Chinese nationalism, these artists’ lives are changing. Some remain in China; others have left for the diaspora. Regardless of where they choose to live, these ba ling hou artists produce works that are provocative and inventive, challenging us to reconsider contemporary Chinese art and, for that matter, the global dimension of art movements at this moment in history.

Twenty-four years ago, Asia Society Museum presented a groundbreaking exhibition, Inside Out: New Chinese Art, introducing American audiences to the scope and depth of contemporary Chinese art production. Even then—when little was known about contemporary art in China—curator Gao Minglu underscored with prescient insight the impact of “transnational forces” on these artists’ lives and ideas. Flash forward to the present and Asia Society Museum offers Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity as an update, demonstrating the emergence in the last decade of a new kind of artist—forged by more recent and current global influences.

Mirror Image asks the question, “What remains of ‘Chinese-ness’ once China has become a fully globalized nation?” Through the artworks of seven artists—all born after 1976 (the year of Mao Zedong’s death), all products of the one-child policy, and all having come of age in an emerging superpower, this exhibition posits that a new transnational sense of self has developed. Do not search for remnants of an East versus West dichotomy that dominates discussions of the older generation of Chinese artists. Instead, strap on new lenses and see these artists as pioneers from a frontier forged by the internet, bootleg DVDs, international brands, and global art history.

The ease of navigating a world of colliding influences is clearly evidenced by the participating artists: Tianzhuo Chen, Cui Jie, Pixy Liao, Liu Shiyuan, Miao Ying, Nabuqi, and Tao Hui. They experiment with materials, genres, iconography, and social roles to convey the way that globalization has upended traditional values and geographically specific ways of looking at the world. You will not find self-Orientalizing gestures of dragons or calligraphy, Ming furniture, or tea ceremonies. Instead, these artists apply a more fluid approach, consistently refusing to be defined by binary oppositional categories.

In this exhibition, there are distinct strategies employed to illustrate ways of interacting with a world in flux. “Sampling”—a playful use of appropriation akin to the work of deejays in music—is strongly in evidence in the photomontages of Liu Shiyuan, the performances of Tianzhou Chen, and the installations of Nabuqi.

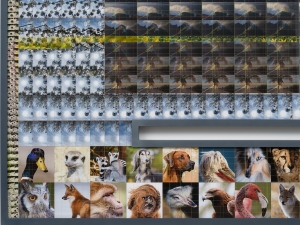

Liu Shiyuan combines found imagery from the internet with her own original video footage to defy linear interpretations, representing the mistranslation pervasive in the global dialogue surrounding contemporary art. Nabuqi postulates the idea that a new universal language may be forming out of the convergence of mass production and culture, using strategies first employed by Pop artists such as Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol. Tianzhuo Chen underscores the altered state of consciousness achieved by “trance” in comparative religions and subcultures, from that of Tibetan Buddhism to that of Burning Man.

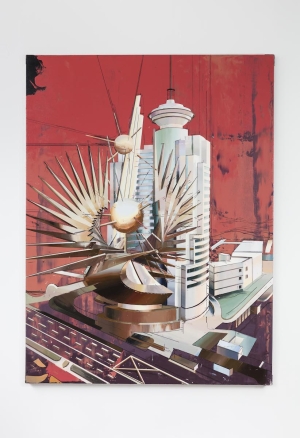

In a similar vein, Cui Jie breaks down lessons learned in the art academy and reinvents painting to convey the crazy juxtapositions and architectural manifestations of time warp on every street corner in major cities in China. Incorporating aspects of Cubism and Surrealism, her urban landscapes transport us to what appears to be a futuristic place, but one that already exists in a city like Shanghai.

The sense of freedom to create one’s own identity is a major concern for this generation of artists. Tao Hui has created a “soap opera” that reinvigorates cliché story lines by featuring an array of characters—queer, transgender, or non-binary—not commonly seen in Chinese television, especially under current restrictions. It is fitting that this faux television series is intended for viewing on TikTok, a Chinese-owned app that fosters a sense of intimacy between the viewer and the video creator, yet is available in China only through its Chinese equivalent, Douyin.

Rather than create false narratives, Pixy Liao makes use of collaborative portraiture in her series, Experimental Relationship, soliciting the cooperation of her long-term partner, Moro. The playful couplings in these photographs offer a critique of the transactional nature of traditional gender roles that is encouraged among young urbanites in Chinese cities. These roles have only become more acute with the repeal of the one-child policy, placing new pressures on Chinese women.

It might be said that this trend towards a “global identity” is not unique to China and is widely in evidence throughout the global art world. But these artists from China most acutely express this transformation in their works because their lives parallel the unfolding transformation in their homeland. China transitioned from a mostly isolated agrarian nation to a land of supercities, international airports, foreign investors, and internet access. These artists grew up in this brave new world, cognizant of Chinese culture while also organically incorporating a wide range of international influences in their lives.

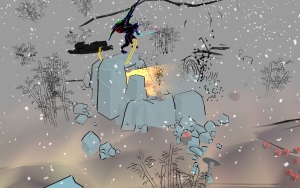

This is especially true for Miao Ying’s videos developed with artificial intelligence. Her computer-generated dialogues do not betray a Chinese accent. Yet on deeper inspection, they reveal a direct correlation with technology as it is employed as a tool of social control in China. She makes art from the underlying algorithms employed in the Great Firewall or the historic roots of China’s social credit system. Miao slyly challenges this system without pointing fingers at specific leaders or laws by referencing in her graphics the medieval Christian practice of purchasing indulgences to reduce the severity of punishment in the afterlife or B.F. Skinner’s novel Walden Two.

Within that social credit system, upholding Chinese values is a key means of earning points under the current leadership in China. Indeed, the notion between “good” and “bad” influences—or eastern versus western influences, which fell out of favor in the early 2000s, has now been revived for political reasons, catalyzed by Xi Jinping’s talks at the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art in October 2014. According to Xi, the artist’s role is to “carry forward the Chinese spirit, bring together China’s might, and inspire all of the nation’s people of every ethnicity to vigorously march towards the future.” The impact of this speech can be felt in the movie industry, television programming, and, to some extent, in museums in China.

Mirror Image recognizes that the clock cannot be turned back. Despite the restrictions and reinvigoration of boundaries due to the pandemic and despite the rise in censorship and nationalism, these artists continue to push forward. We no longer view them as ambassadors from an exotic land but as representatives of a world we share. Their artistic practices contribute to the visual language being shaped on the global stage towards a more pronounced transnationalism as the world grows more divisive.

—Barbara Pollack

Curating Contemporary Asian Art: A Conversation

Thursday, October 6 at 6:30 p.m.

Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity — Artist Talk with Barbara Pollack, Pixy Liao, Miao Ying, Nabuqi, and Tao Hui

Thursday, July 21 at 7 p.m.

Watch the video of the talk:

"A journey into the taboos and prohibitions of present-day China." —Artforum

Wired interview with participating artist Miao Ying on her work in the show, Surplus Intelligence.

"The museum presents works by seven artists, all born after 1976, for whom the binary of East versus West is essentially moot."—The New Yorker

"a unique look into the lives of artists who grew up in post-Mao mainland China."—Galerie magazine

"arguing...for a reevaluation of what it means to be 'Chinese' in today’s globalized world."—RSAA blog

Read the press release for the exhibition here.

Support for Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity is provided by George and Mary Dee Hicks, China Guardian, Asia Society Global Arts Collectors Circle, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and New York State Council on the Arts.