Experience the exhibition — virtually!

Impermanence is a pervasive subject in Japanese thought and art. Through masterpieces of calligraphy, painting, sculpture, ceramics, lacquers, and textiles drawn from two of America’s greatest Japanese art collections, this exhibition examines Japan's unique and nuanced references to transience. Objects span from the Jōmon period to the twentieth century. From images that depict the cycle of the four seasons and red Negoro lacquer worn so it reveals the black lacquer beneath, to the gentle sadness evoked in the words of wistfully written poems, the exhibition demonstrates that much of Japan's greatest art alludes directly or indirectly to the transient nature of life.

Order the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue online at AsiaStore.

In an age when news headlines regularly warn us of the dire effects of climate change, the transience of life may seem to be on people’s minds more than ever. Yet the concept is one that has resonated with humans across time and cultures. In Japan, the notion is particularly nuanced and the aesthetic or symbolic suggestion of ephemerality is key to the appreciation of much of Japan’s artistic production. Longing, fear, loss, and feelings of helplessness are part of the human condition. It is difficult not to be anxious about the transient nature of our lives. However, the expression of ephemerality and its related feelings vary from culture to culture. In this exhibition, more than sixty masterpieces of calligraphy, painting, sculpture, ceramics, lacquers, and textiles drawn from two major collections, the Collection of John C. Weber and Asia Society’s Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, are presented to elucidate the art of impermanence in Japan.

This exhibition provides a sense of how the theme of impermanence has emerged in various forms in the arts of Japan over many centuries. In Japan, as throughout much of the world, early sculptures, vessels, and amulets come from contexts that have largely been lost, but modern humans feel compelled to try to scientifically reconstruct them. This loss of history and the related desire to retrieve it is something to which we can all relate. Historically, Buddhism had a major impact on the development of Japanese culture and remains influential within the country today. For Buddhists, the concept of impermanence is closely related to the understanding of and the desire to escape from the cycle of rebirth and death through enlightenment. During Japanese tea gatherings (chanoyu) participants focus on aesthetic details that elicit feelings of wistfulness associated with the transience of life. Moreover, allusions to the transience of life have appeared in Japanese literature for centuries. The emotional associations with the ephemeral run so deeply in Japan and are so highly regarded that visual references are reflected though much of the high and low art of Japan, from elegantly mounted calligraphy for the tearoom to bold kimono patterns.

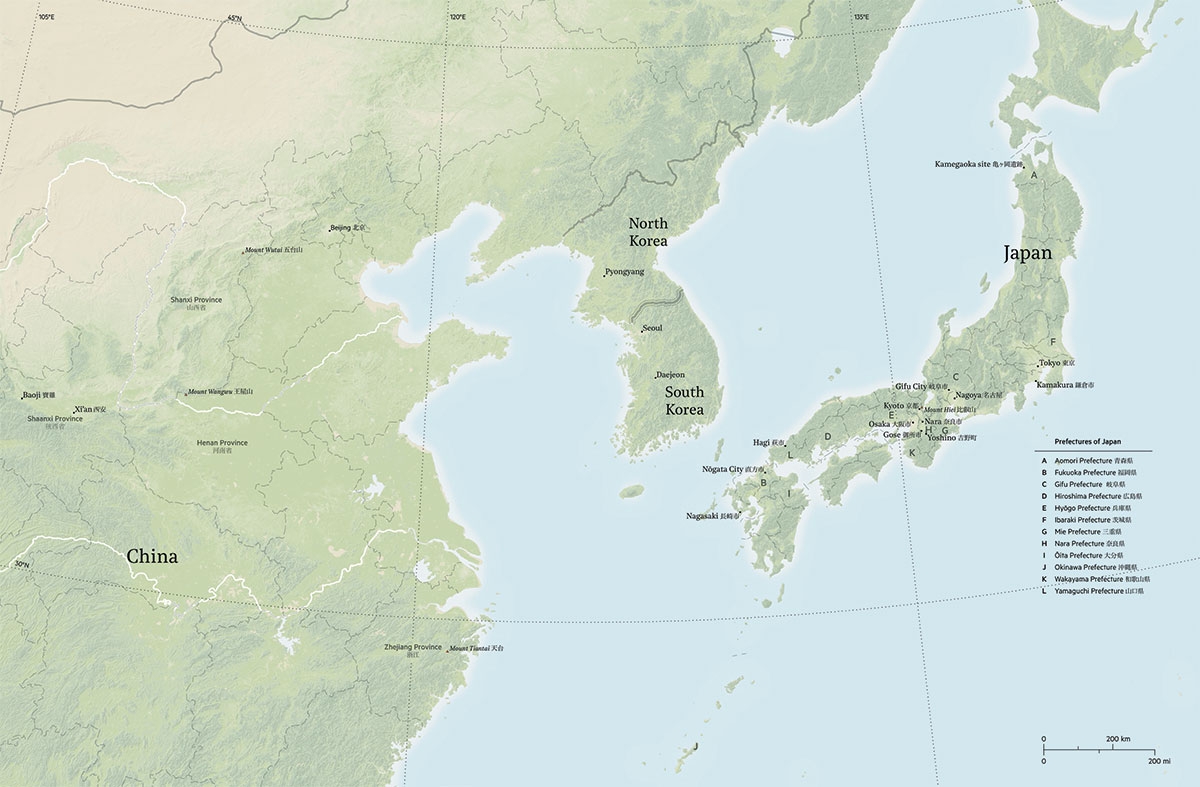

The survival of fragments of ancient cultures from preliterate Japan highlights the fragility and ephemerality of the past writ large. We do not know what language the earliest people spoke and if there were original names for Japan’s three ancient civilizations they did not survive. Today the earliest of these is called Jōmon (ca. 15,000–300 BCE), which means “cord marking,” a term inspired by impressed patterns on some of the ceramics produced by these Neolithic people. The subsequent Yayoi civilization (ca. 300 BCE–300 CE) got its designation from a find site, Yayoi-chō, a district in Tokyo. The Tumulus period (300–710) refers to the distinctive grave mounds that characterize the burial practice of its people. The objects presented in this exhibition section from these three past epochs offer tantalizing clues about why they may have been made.

Ceramic pieces associated with Kamegaoka, the first Jōmon site to receive notice in Edo-period (1615–1868) Japan, are on view: two figures known as dogū, a bowl, as well as a flame-style vessel. At least three of these appear to have had some kind of religious or ceremonial purpose. Jōmon culture gradually was subsumed by waves of immigrants from the Asian mainland, mainly Korea, arriving first on the southernmost island of Kyushu and bringing the culture later called Yayoi. Rice agriculture, as well as bronze and iron working, are among the practices they brought that radically influenced Japanese civilization. The Yayoi jar in this exhibition section typifies the thinner, harder, higher quality pottery developed by the Yayoi people under the aegis of immigrant potters. Another wave of immigrants brought additional skills that enabled independent Japanese clan rulers to consolidate power during the Tumulus period. Two large haniwa—guardian sculptures placed around tombs—draw attention to the martial nature of this period and the complex transfer of materials and styles of military dress across East Asia. The meaning of other objects discovered in tomb settings is completely enigmatic, such as the striking bracelet-like object of green tuff that is too small, heavy, and bulky to be worn.

“Life is suffering,” proclaimed the Historical Buddha, Shaka (Shakyamuni), as the first of his Four Noble Truths. He goes on to suggest that because impermanence, called mujō in Japanese, is a basic existential condition, to cling to things—rather than realize that ultimately all is formless and that the physical world is illusion—is the source of human suffering. Recognizing the existence of mujō is an essential step toward the elimination of desire and achievement of enlightenment.

Buddhism is a religion that is deeply rooted in but not originally native to Japan. Though it originated in India, according to Japan’s earliest historical accounts, it was not until around the middle of the sixth century when the ruler of Korea’s Baekje Kingdom sent Japan’s Yamato ruler an image of Shaka Buddha in gilt copper, several flags and umbrellas, and a number of Buddhist texts that Japan’s rulers embraced the religion. Several schools of Buddhism eventually took hold in Japan. Mahayana, which stresses universal salvation rather than the salvation of the individual, and esoteric Buddhism, which focuses on doctrines and practices transmitted from master to disciple and mystical formulas, were popular in Japan in various forms. In this exhibition section, relics, symbolic tokens of Shaka Buddha’s physical remains, and sutras, religious texts, capture the essence of the Buddha and his path in aesthetic forms that Japanese believers found especially appealing. The representations of several buddhas said to inhabit different Buddhist paradises, along with bodhisattvas, enlightened beings who aid sentient beings in their quest to cease the cycle of rebirth and suffering, and wrathful Buddhist deities attest to how popular these forms of Buddhism became in Japan.

Whether commissioned or produced by royalty, priests, or laypersons, the works on view in this exhibition section—from the section of an eighth-century sutra attributed to Emperor Shōmu to a splashed-ink landscape from the late fifteenth century by Zen Buddhist priest Josui Sōen, to the unknown craftsman who created the dynamic Namikiri Fudō Myōō sculpture—reflect the Buddhist desire to gain merit in hopes of ultimately breaking the endless cycle of suffering.

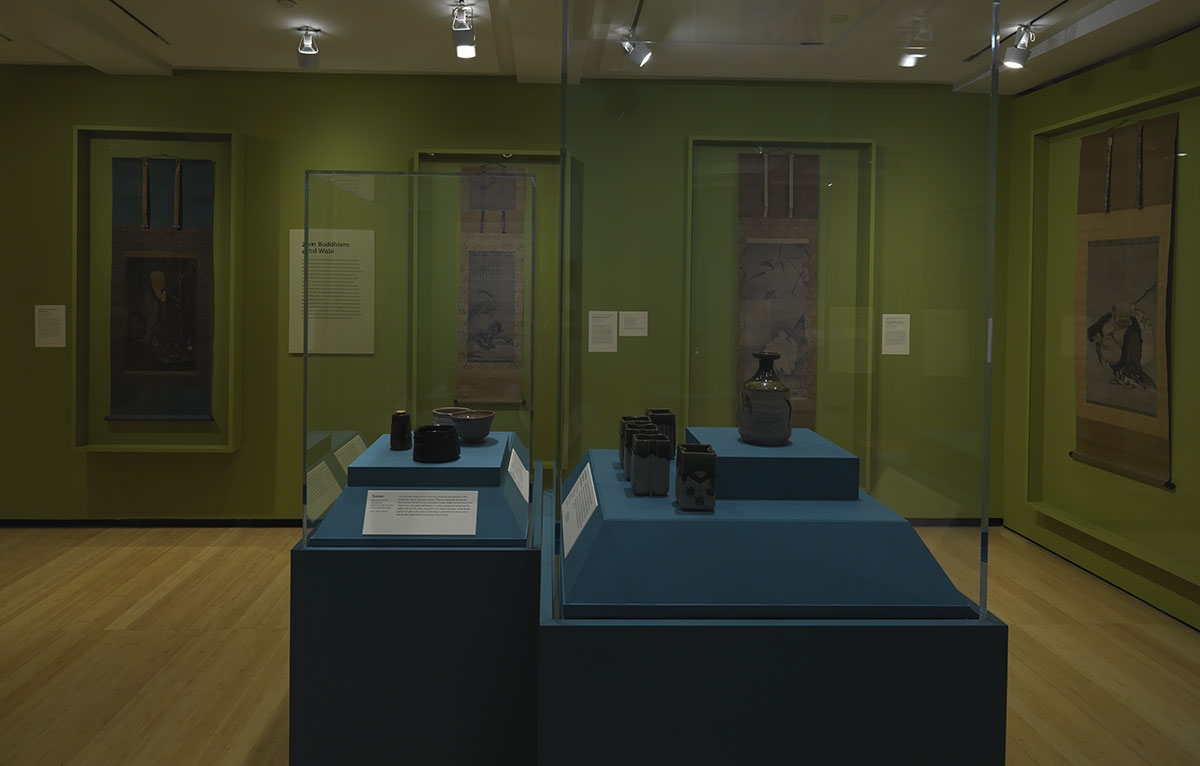

Zen Buddhism (which originated in China where it is called Chan Buddhism) emphasizes master-to-pupil teaching and meditation. Portraits of patriarchs and teachers were particularly venerated due to the importance placed on personal dissemination of religious knowledge and the lineage that resulted. Most important for the evolution of Japanese taste, Zen practitioners linked their religious practice with the arts of poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Priests, monks, and other adherents engage in these cultural activities at least in part as exercises to help spark their enlightenment. The Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi, valuing the pleasure taken in austerity, aloneness, and an appreciation of objects weathered by time, is associated with these practices. Zen Buddhists feel that focusing on Buddhist beings is largely extraneous to the goal of enlightenment. However, depictions of these beings join calligraphy, landscapes, and bird and flower compositions as preferred imagery for their religiously nuanced washy monochrome or largely monochrome and austerely rendered paintings.

Japanese tea drinking began in the monastery and spread to the elite sphere of medieval courtiers and warriors. The fifteenth and sixteenth century saw the emergence of a quintessentially Japanese form of tea gathering with roots in Zen Buddhist philosophy called chanoyu, the Way of Tea. A gathering can take place on any sort of occasion and might last from twenty minutes to four hours. During these carefully orchestrated tea events, participants quiet their minds; focus on their senses; appreciate the beverage, their intimate surroundings, and aesthetically compelling objects; and tap into feelings of wistfulness associated with the transience of life.

Murata Shukō (Shukō or Jukō, 1423–1502) who has been called the father of the tea ceremony, advised practitioners to avoid “overbearance [and] attachment to self.” He introduced the term wabi, related to the notion of simplicity and restraint, to tea. Implicit in wabi is the idea that material things are mutable. As part of this, he championed finding satisfaction in the unassuming, like a weathered hut, a cracked bowl, or the random glaze effects resulting from wood ash flying about the kiln during firing. A striking example of the latter is visible in the Iga water jar in this exhibition section.

The school of Tea founded by Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) emphasizes the qualities of both wabi and sabi. For Rikyū, the latter is a term that evokes the qualities of old age, a flower past its bloom, or rust on metal. He advocated for the inclusion of imperfect ceramic and lacquer objects in contemplative tea gatherings. The aesthetic he favored is embodied, for example, in the rugged Hagi tea bowl or the slightly damaged Shino object in this exhibition section. He also considered the hanging scroll featuring calligraphy or painting to be the most prized object in the tearoom. Rikyū’s student, Furuta Oribe (1544–1615), a former military general who studied Zen Buddhism, catered his style of tea to the military class. Oribe’s taste is characterized by the rough yet bold, asymmetrical aesthetics of the Oribe dishes in this exhibition section. He also welcomed elements of the new into chanoyu, for example serving tea and related meal in recently made ceramics.

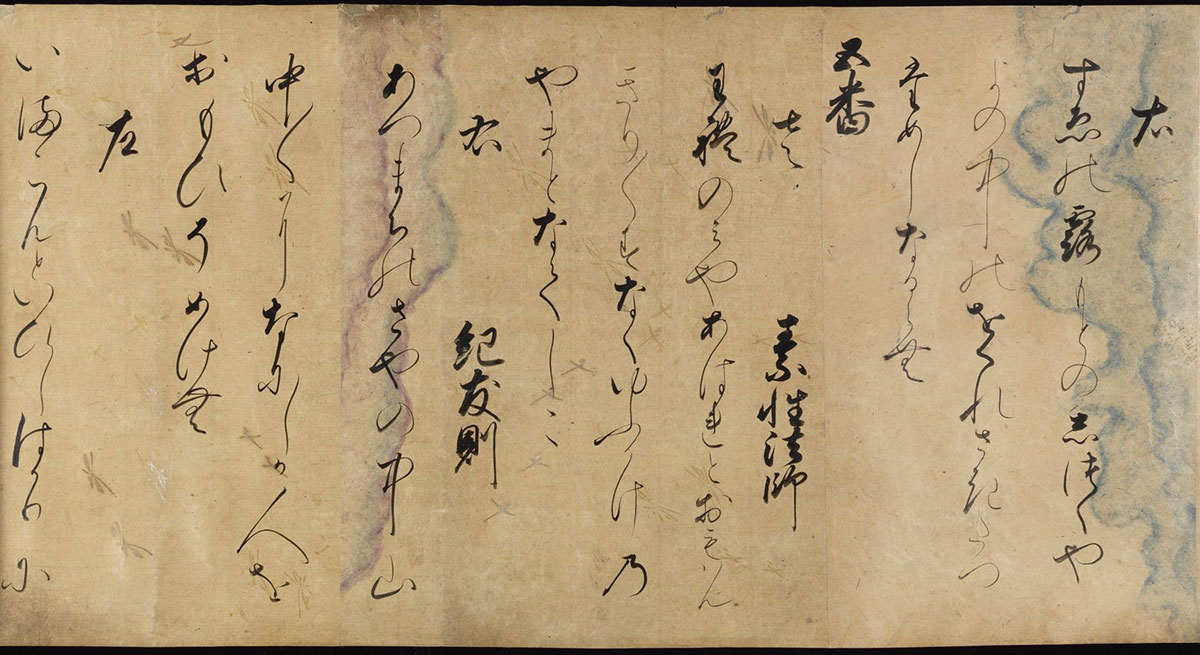

Laments about ephemeral things fill Japan’s earliest writings. The word sabi (loneliness), which Japanese learned from Chinese Tang dynasty poetry, originally connoted wretchedness. Over time, it took on the notion of an introspective type of beauty brought on by solitude. From this melancholy perspective something becomes all the more beautiful because it is worn from use. The four seasons connote impermanence through cyclical change and serve as a prevalent theme in Japanese poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Autumn is charged with additional, poignant meaning as a forlorn time because the beauty of its blazing colors fades with the chill of winter.

Writings invoking the imagery mentioned above as well as idealized portraits of Japan’s early poetic geniuses are on view in this exhibition section. One of them, the great Ki no Tsurayuki (872–945), wrote in the Preface of a poetry anthology, Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Waka Poetry (Kokin wakashū), “Japanese poetry has the human heart as seed and myriads of words as leaves. It comes into being when men use the seen and the heard to give voices to feelings aroused by the innumerable events in their lives.” It is through this mono no aware (elegant sensibility to the nature of things) that Japanese poets express themselves.

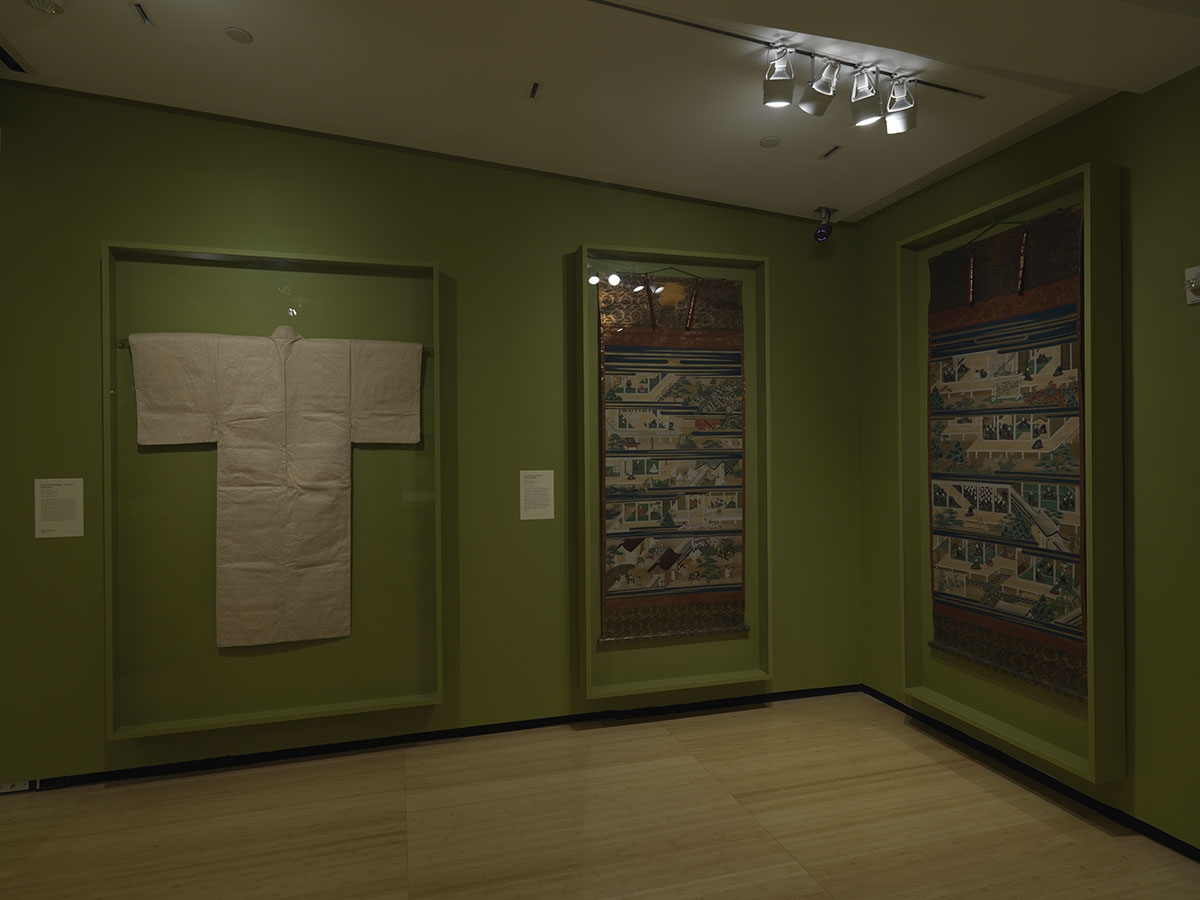

The categories of poems in the imperial anthologies overlap with themes in Lady Murasaki’s (d. ca. 1019) famous novel The Tale of Genji. Sorrow and impermanence figure prominently throughout the novel as do love, seasons, and poetry. The delicately hand-painted Genji Cards in the exhibition further attest to the popularity of the novel, which was profusely quoted, studied, adapted, and spoofed. The pathos associated with impermanence was fully ingrained in Japanese culture when the warrior, tea aficionado, and waka poet Hosokawa Sansai (1563–1646) wrote that the sight of a helmet lying broken on a battlefield was “something truly heroic and beautiful.” The same could be said of a tattered fan that graces a nineteenth-century battle coat designed for ceremonial use, seen in this exhibition section.

Starting in the seventeenth century, the term mono no aware became associated with popular paintings and prints from Japan’s pleasure quarters, which were perceived as transient, yet enjoyable worlds. Similarly, pictures of the Floating World (ukiyoe) were so named because of the transient (floating), but intensely pleasurable nature of what they show on the surface. In Japan beautiful women were already linked with cherry blossoms, which bloom quickly then scatter. The brothel quarters capitalized on this connection by importing cherry trees in tubs for their few weeks of bloom in early spring. Images of the beautiful women of the pleasure quarter, such as the two hanging scroll paintings of them in this exhibition section, both of which also feature blossoming cherry trees, were luxury commissions by wealthy merchants and other well-placed people.

To enjoy Asia Society's free audio guide for "The Art of Impermanence: Japanese Works from the John C. Weber Collection and Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection" just look for the audio icon next to select artworks in the exhibition.

For easier mobile access, listen at Soundcloud.

MEMBERS-ONLY RECEPTION AND LECTURE

The Art of Impermanence

Tuesday, February 11, 2020 • 6-9 p.m.

Reception from 6-8 p.m.

Members-only lecture: 6:30-7:30 p.m.

Galleries open until 9 p.m.

Docent-led tours at 6, 6:45, and 7:45 p.m.

As part of the members' opening reception and activities, Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator of Traditional Asian Art at Asia Society and curator of “The Art of Impermanence” will examine themes drawn from the exhibition.

LECTURE

My Thoughts Dyed with You: Perspectives on Impermanence in Japanese Art

Wednesday, March 11, 2020 • 6:30-8 p.m.

Curator Sinéad Vilbar explores how commentaries on Buddhist scripture and the production of poetry in Japan communicated the ephemeral nature of human existence.

[WEBCAST ONLY] LECTURE

Monuments to Impermanence: New Inspirations From Ancient Japanese Stone Circles and Burial Mounds

Tuesday, March 31, 2020 • 6:30-8 p.m.

Archaeologist Simon Kaner examines the concept of impermanence as suggested by the monuments of preliterate prehistoric Japan.

[WEBCAST ONLY] LECTURE

Tattered Fans and Talismans: The Symbolism of Battle Fans and the Ethos of Impermanence

Thursday, May 28, 2020 • 6:30-8 p.m.

Art historian Melissa McCormick explores the role of fans in Japanese warrior culture, from talisman to icons of ephemerality.

Due to ongoing concerns about community transmission of COVID-19, the remaining exhibition lectures have been suspended. We are working closely with the speakers to digitally broadcast the lectures at a later time and will update you when more details are confirmed.

Find all the recordings of lectures and podcasts related to the themes of The Art of Impermanence here:

The Art of Impermanence: A Lecture by Exhibition Curator and Asia Society Museum John H. Foster Senior Curator of Traditional Asian Art Adriana Proser

Asia In-Depth Podcast: The Art of Collecting with John C. Weber and Adriana Proser

Subscribe in iTunes ∙ RSS Feed ∙ Download ∙ Full Episode Archive ∙ Listen on Spotify

My Thoughts Dyed With You: Perspectives on Impermanence in Japanese Art

Lecture by Sinéad Vilbar, Curator of Japanese Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art

Monuments to Impermanence: New Inspirations From Ancient Japanese Stone Circles and Burial Mounds

Lecture by Simon Kaner, Executive Director of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures and Director of the Centre for Japanese Studies, University of East Anglia

Tattered Fans and Talismans: The Symbolism of Battle Fans and the Ethos of Impermanence

Lecture by Melissa McCormick, Professor of Japanese Art and Culture at Harvard University

Installation views of “The Art of Impermanence: Japanese Works from the John C. Weber Collection and Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection” at Asia Society Museum, 2020. Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2020

Support for “The Art of Impermanence: Japanese Works from the John C. Weber Collection and Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection” comes from the Japan Foundation and an anonymous donor.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Global Council on Asian Arts and Culture, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and New York State Council on the Arts.