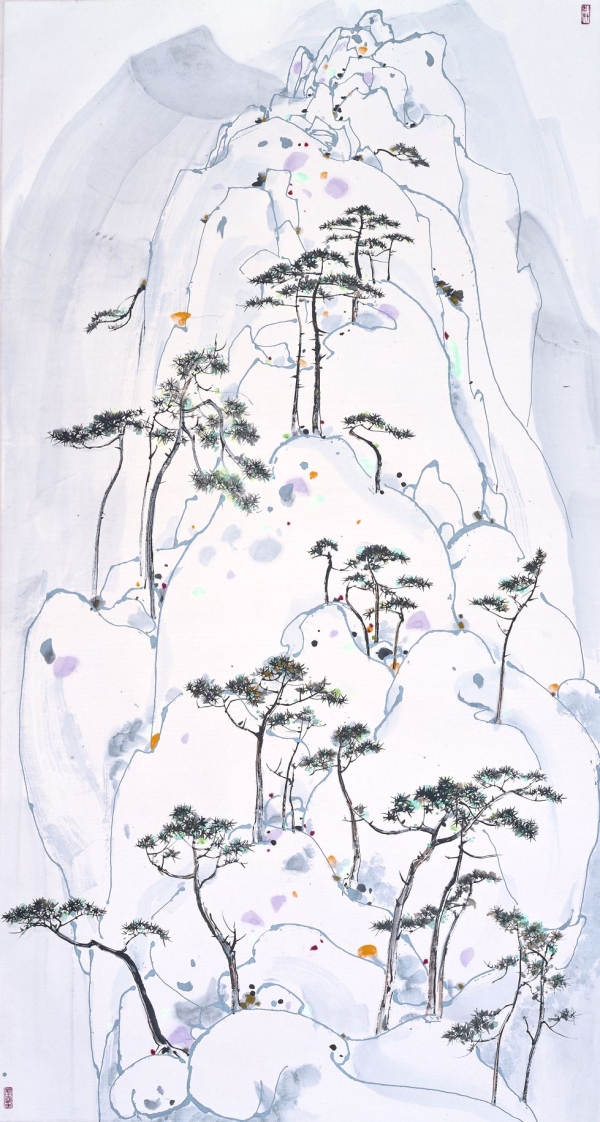

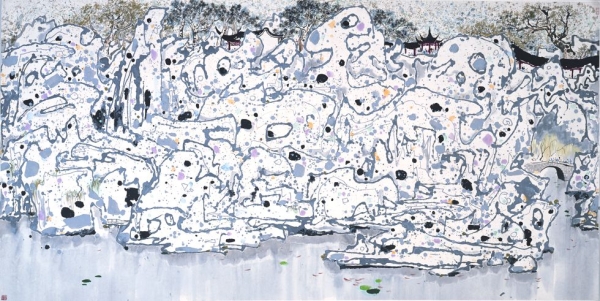

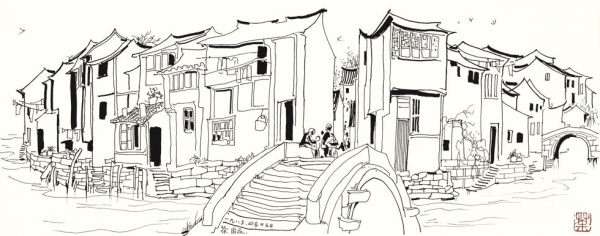

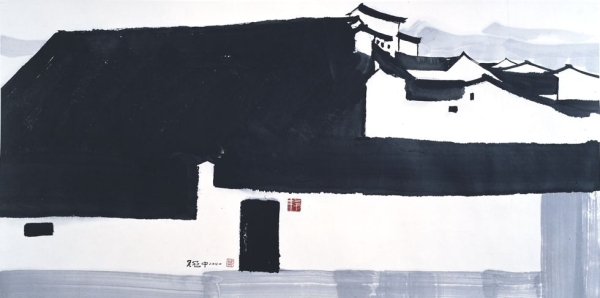

Sneak Peek: The Revolutionary Chinese Ink Paintings of Wu Guanzhong

Asia Society Museum's new exhibition, Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong, which opens tonight in New York City, marks the first posthumous retrospective in the United States of the pioneering Chinese artist who passed away at the age of 90 in 2010. As The Wall Street Journal reports, Wu is well known in China and throughout Asia for "his experimental, sometimes abstract variations on traditional Chinese ink painting." Last year, an oil painting of his from the 1970s fetched more than $23 million at auction in Beijing.

Above, you can view 10 of the 54 ink-on-paper pieces featured in the exhibition. (We strongly encourage you to use the "enlarge" feature — these paintings deserve to be enjoyed as big as possible!)

Wu studied in Paris in the 1940s and the Western-style works he produced in China in the 1950s made him a target during the Cultural Revolution, writes The Wall Street Journal:

Wu is said to have destroyed much of his early work as the Red Army approached his home in 1966. They seized his belongings and forbade him to paint or write. He then spent several years serving hard labor in a rural town. Publicly chided, he was forced to condemn his own work and ideas.

As restraints loosened in the early 1970s, Wu rededicated himself to his work, focusing intently on the ancient Chinese medium of ink.

"It was very much the opposite of what younger artists were doing in the 1970s and '80s," says Asia Society Museum director Melissa Chiu, who curated the exhibition with the Shanghai Art Museum's Lu Huan. "They were very interested in Western art, but he had already done that. So he turned his attention to traditions of the past."

A story in today's New York Times says Wu's show at Asia Society Museum, which runs through August 5, is an example of "a more sophisticated approach" from China in sharing its art and culture with the rest of the world. Chinese museums are now making decisions with less interference from the central government's propaganda officials.

The New York Times goes on to explain how this collaboration between Asia Society and the Shanghai Art Museum came about:

The genesis for the exhibition came in 2008, when the director of Asia Society Museum, Melissa Chiu, visited a retrospective of Wu’s work at the Shanghai Art Museum. The idea evolved with the cooperation of Mr. Li Lei, the museum’s director, and the artist, whom Ms. Chiu visited at his studio in Beijing ...

Wu’s art appeals to Chinese collectors partly because, in contrast to some of the high-selling avant-garde artists who went to the West after the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution and adapted Western trends, Wu returned to Chinese tradition. Mr. Li said he hoped Wu could be a bridge between the two cultures for American art lovers.

The choice of works for Asia Society was a joint effort between her and Mr. Li, Ms. Chiu said. The two museums shared the costs, with the Chinese paying for all framing, packing and shipping, a welcome contribution in an era of austere budgets, she said.

“I haven’t heard of the Chinese government paying those costs before, so this is a new chapter in the China-U.S. art relationship,” she added.

For more images, and more about Wu, please visit the official exhibition homepage.