Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong

Landscape | Architecture and the Everyday | Abstraction | Quotes from Wu Guanzhong

Press | Selected Readings | Credits | Exhibition Catalogue

Wu Guanzhong (1919–2010) stands as one of the most important artists of twentieth-century China. Born in Jiangsu Province, Wu studied art at the National Academy of Art in Hangzhou (today’s China Academy of Art) and, from 1947, in Paris at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts. He returned to China after three years and taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. His works were condemned before and during the Cultural Revolution because his oil paintings did not comply with the political interests of the time. In spite of this he continued to paint and emerged as a national cultural figure whose works came to be celebrated inside and outside China. He is also well known for his eloquent writings on art and creativity that sometimes led to controversies and spawned heated debates among Chinese artists and intellectuals. Wu Guanzhong created works that embody many of the major shifts and tensions in twentieth-century Chinese art—raising questions around individualism, formalism, and the relationship between modernism and cultural traditions.

With a career spanning over sixty years, the selection of paintings in this exhibition focuses on some of his best works in the medium of ink and spans the decades from the mid-1970s to 2004. It is notable that Wu began to work more extensively in ink in the 1970s in his mid-career—turning to a traditional medium at a time when most artists looked to western art for inspiration. The exhibition traces the development of Wu’s work during this period with a thematic focus illuminating the rich historical legacy of ink painting in China, and also representing his radical individual style steeped in his strong belief in formalist principles. Wu pushed the boundaries of our understanding of how a traditional medium of ink can be made new for a new century.

Landscape

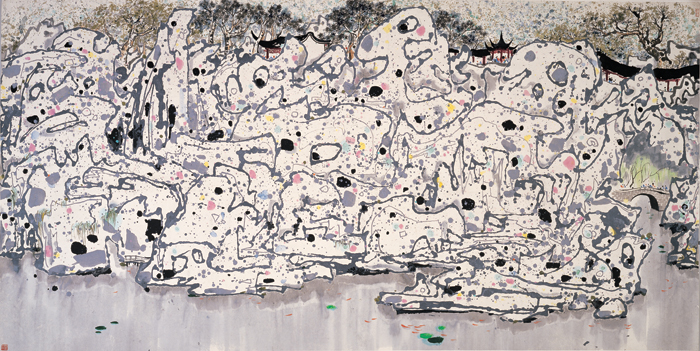

Lion Woods, 1983, ink and color on rice paper, 173 x 290 cm, Shanghai Art Museum

Wu Guanzhong often compared his revolutionary approach to ink painting to the way a kite is navigated; not flying too far from the ground. The use of ink and wash clearly reveals his solid grounding in the centuries-old tradition of Chinese ink landscape painting. Monumental mountains in Wu’s paintings echo the regal presence of mountain peaks in the iconic landscape painting Early Spring by Guo Xi (1000–ca. 1090), dated to 1072. Some other works by Wu show influences of painters from the Song dynasty (960–1279) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in the compositions and the types of brushstrokes he uses to add a variation in texture and an atmospheric effect. However, he has also created works that are fundamentally different from the tradition, particularly in his use of bright colors, liberal use of wash, and radical compositions based on an interest in formalism. This section comprises several examples of drawings from nature that Wu produced during his sketching trips throughout China and paintings from the late 1970s to 2000 that trace his constant reflection on tradition and experimentation.

Architecture and the Everyday

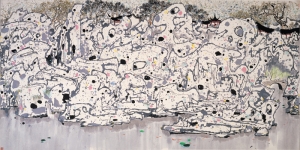

A Big Manor, 2001, ink and color on rice paper, 70 x 140 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

A Big Manor, 2001, ink and color on rice paper, 70 x 140 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

Where traditional ink paintings emphasized the grandeur and majesty of the natural environment over small-scale pavilions or other architectural elements, the most distinct compositions that Wu created are found in those paintings depicting rural yet grand homes and towns that emphasize a constructed, man-made environment. Rather than including buildings as a small part of painting, he extracted geometric beauty and a structural rhythm from architecture. To Wu, whether artists are painting buildings, mountains, rivers, grass, or trees, it is of primary importance that they paint with feeling.

Abstraction

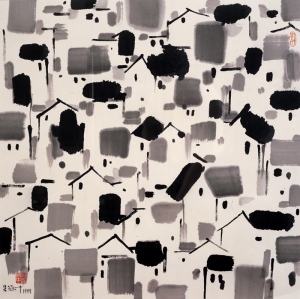

Alienation, 1992, ink and color on rice paper, 69 x 138 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

In his later period Wu’s landscapes became more and more abstracted. Most of these works are from after 1990 and show an intention to represent states of being, emotions, and concepts over more realistic representation. For example, rather than showing birds-eye or long-view perspectives usually associated with ink landscape paintings, the works provide a closer view as if the viewer is fully immersed in the environment. On this subject he has said, “I want to express the transformations in space and time that occur in my mind. The many forms I see with my eyes inspire the unpredictable transformations that I haven’t yet seen.”

Quotes from Wu Guanzhong

Select Quotes of Wu Guanzhong from Abstraction and Form, Meishu (Fine Arts) in 1992, translated by Valerie C. Doran for the exhibition catalogue Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong (New York: Asia Society, 2012)

"The beauty of abstract form is extracted from concrete objects and distilled according to the intrinsic qualities of the form. The art of root carving retains certain concrete aspects, and it is considered very beautiful. This is called transforming the common and useless into the marvelous and the quality of abstract beauty is foremost in creating this effect. On the other hand, we also see some artworks that transform the marvelous into something common and useless."

"The relationship between semblance and non-semblance is in fact the same as the relationship between concrete and abstract. What exactly constitutes spirit resonance and lifelike motion (qiyun shengdong) in Chinese traditional painting? Whether in landscape or in flower-and-bird painting, it lies in the expressive difference between motion that has spirit resonance and motion that does not. Within this there is the question of the harmony or conflict between the abstract and the concrete, and the factor of either beauty or ugliness that hovers just beyond. The principle of analysis for form is the same as for music."

"The fundamental elements of formal beauty comprise form, color, and rhythm. I used eastern rhythms in the absorption of western form and color, like a snake swallowing an elephant. Sometimes I felt I couldn’t gulp it all down and I switched to using [Chinese] ink. This is why in the mid-1970s I began creating a large number of ink paintings. As of today in my explorations I still shift between oil and ink. Oil paint and ink are two blades of the same pair of scissors used to cut the pattern for a whole new suit. To nationalize oil painting and to modernize Chinese painting: in my view these are two sides of the same face."

"Brush-and-ink is misunderstood as being the only choice for life and the future path of Chinese painting, and the standards of brush-and-ink painting are used to judge whether any work is good or bad. Brush-and-ink is a technique. Brushwork is embodied within technique, technique is not embodied within brushwork, and technique is only a means that serves the artist in the expression of his emotions."

"Whenever I am at an impasse, I turn to natural scenery. In nature I can reveal my true feelings to the mountains and rivers: my depth of feelings toward the motherland and my love toward my people. I set off from my own native village and Lu Xun’s native soil."

This exhibition has been organized by the Shanghai Art Museum and Asia Society Museum.

The curators of the exhibition are Melissa Chiu, Asia Society Museum, and Lu Huan, Shanghai Art Museum.

Asia Society Museum Staff

Melissa Chiu, Museum Director and Senior Vice President, Global Arts and Cultural Programs

Marion Kocot, Director, Museum Operations

Nancy Blume, Head of Museum Education Programs

Clare McGowan, Collections Manager and Registrar

Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Curator for Traditional Asian Art

Jacob M. Reynolds, Associate Registrar

Miwako Tezuka, Associate Curator

Davis Thompson-Moss, Installation Manager

Donna Saunders, Executive Assistant

Special thanks to Zixuan Feng and Renny Grinshpan, Museum Interns.

Press

New York Times Review - July 19, 2012

Selected Readings

Bush, Susan and Hsio-yen Shih. Early Chinese Texts on Painting. Cambridge, MA: published for the Harvard-Yenching Institute by Harvard University Press, 1985.

Chow, Kwok Kian. “The Art of Wu Guanzhong: A Decussation of Cultures.” Passage (May/June 2009), 16–19.

Farrer, Anne with contributions by Michael Sullivan and Mayching Kao. Wu Guanzhong: A Twentieth-Century Chinese Painter. London: British Museum Press in association with Mei Yin, 1992.

Hay, Jonathan. Shitao: Painting and Modernity in Early Qing China. Res Monograph Series. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Lee, Sarah, ed. An Unbroken Line: The Wu Guanzhong Donation Collection. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2009.

Lim, Lucy, ed. Wu Guanzhong: A Contemporary Chinese Artist. San Francisco, CA: Chinese Culture Foundation of San Francisco, ca. 1989.

Jiang, Mei. Critical Biography of Wu Guanzhong’s Art. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2008.

Mok Yee Wah, Pauline, ed. Wu Guanzhong: A Retrospective. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1987.

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

Wu, Guanzhong. Collected Writings on Painting. Beijing: People’s Literary Press, 2009.

—————. “Formalist Aesthetics in Painting.” Translated by Michelle Wang in Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, 14–17. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Excerpted from a text originally published as “Huihua de xingshi mei,” Meishu (Fine Arts) 138, no. 5 (1979): 33–35, 44.

—————. Limited Collector’s Edition: Dedicated to the 90th Anniversary of Wu Guanzhong’s Birth. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2009.

—————. Lofty Integrity: Donation of Works by Wu Guanzhong. Hong Kong: Leisure and Cultural Services Department, 2010.

—————. Painting from the Heart: Selected Works of Wu Guanzhong. Beijing and Chengdu: Foreign Language Press and Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House, 1990.

—————. Recent Ink Paintings of Wu Guanzhong, A Contemporary Chinese Artist: Oil Paintings and Sketches. Paris: Musée Cernuschi, 1993.

—————. Shujia fenben (Which is the model?). Chengdu: Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House 1987.

—————. Wu Guanzhong: Ancient City. Hong Kong: Han Mo Xuan Publishing Co., Ltd., 1997.

Wu, Keyu, Jing Yu and Tan Ban Huat, eds. Sketches by Wu Guanzhong. Singapore: L’Atelier Productions Pte. Ltd., 1993.

Wue, Teo Han. “Wu Guanzhong: Chinese Master Artist.” Arts of Asia 42, no. 2 (March/April 2012): 95–109.

Credits

Support for Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong is provided by the Take a Step Back Collection.

Asia Society also acknowledges the generosity of China Guardian Auctions Co., Ltd.

Support for Asia Society Museum provided by the Asia Society Friends of Asian Art; Asia Society Contemporary Art Council; Arthur Ross Foundation; Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions; Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund; National Endowment for the Humanities; Hazen Polsky Foundation; New York State Council on the Arts; and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

Plan Your Visit

725 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10021

212-288-6400

.png)

.png)