Gallery: See Modern China Through the Lenses of Contemporary Artists

How did China become the largest trading nation in the world and what stories do contemporary Chinese artists tell about their country’s economic and social transformation? These questions are explored at length in DE/CONSTRUCTING CHINA: Selections from the Asia Society Museum Collection, on view through July 19 at Asia Society Museum in New York. Featuring a selection of videos and photography from eight artists in the museum’s collection, the exhibition explores the evolution of China’s social and physical landscape and its ongoing impact on society.

To learn more about the exhibition, Asia Blog caught up with Michelle Yun, senior curator of modern and contemporary art at Asia Society.

Could you tell us about the inspiration for this exhibition?

I organize thematic shows at Asia Society every summer that draw from our permanent collection of contemporary video and photography, which was founded in 2007. When I started planning for this year’s summer exhibition, it was around the time that China was declared the world’s largest trading nation, surpassing the United States. So I started looking at our collection and thinking about how I could talk about this milestone.

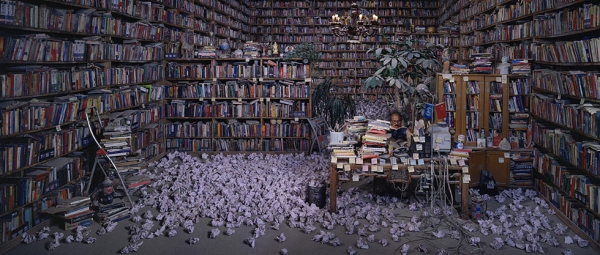

A lot of contemporary Chinese art since the mid 1990s has focused on the shifting urban landscape. China’s social and physical evolution seemed like a common theme in our collection. Personally I’ve been thinking a lot about the evolution of Chinese landscape painting and how contemporary Chinese artists have appropriated or evolved the genre. Today, the genre no longer is limited only to traditional ink painting; artists like Cao Fei are creating landscapes in virtual reality or with digital media. So that’s a larger idea that I’ve been playing with for some time, and I wanted to see how it played out with our collection.

What’s significant about DE/CONSTRUCTING CHINA, the title of the exhibition?

Since the 1990s, China has made a huge effort to gentrify its urban centers. While I was considering this rapid rate of construction, I also thought about the idea of constructing a nation — not just in the physical sense, but in building its economy and political strength in order to construct a world power.

The “deconstruction” part of the title is not necessarily taking this apart, but parsing this evolution. When you deconstruct something, you’re trying to understand it. I feel like the artists who are included in the show are trying to do that in their work. In many cases, they are examining how China’s economic growth reverberates in other aspects of the country’s cultural evolution.

What is unique about how these pieces engage with current issues?

They are certainly presenting direct commentary on what’s going on in China. I think they are trying to illuminate issues and share their experiences. For example, I see Cao Fei’s i.Mirror by China Tracy (AKA: Cao Fei) Second Life Documentary Film as a self-portrait. The video documents her real experiences in the virtual platform of Second Life. It illuminates how the paradigm has shifted, especially for the younger generation, through greater cosmopolitan exposure in large part due to the economy. These experiences and exchanges with people outside China have really liberalized the outlook and experiences of certain contingencies of the population.

How does DE/CONSTRUCTING CHINA speak to the larger artistic landscape in China today?

Contemporary Chinese art is a relatively young field — it really only started at the end of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s. And in the 1990s after the Tiananmen Square protests, many avant-garde artists had to go underground, and so there were no public platforms to exhibit or sell artwork and there was no commercial gallery system.

These artists had to change the nature of their artistic practice. Many artists turned to performance art, and then to video and photography as the means of documenting their performances. For example, the 1995 Lin Yilin video in the exhibition was the documentation of a performance. These guerilla performances were under the radar and people could mobilize quickly. The artists held exhibitions in apartments, warehouses, or other nontraditional places, and promoted them by word of mouth.

Many of the earlier videos from the 1990s were related to performance-based art, whereas Ink City from 2005 by Chen Shaoxiong (a contemporary of Lin Yilin) has a different rationale behind its creation. I find there is now more emphasis on animation and that the way people are creating videos has evolved along with advances in technology.