Photos: Across Generations, Bangladeshis Unite to Demand a Death Sentence

From up top, it looks like a perfect cross — the intersection at Shahbag. In Bangladesh, if there was ever a place where you could literally stand at a crossroad, this major junction that stands between Old Dhaka and New Dhaka would be it. On any other day the four major thoroughfares that crisscross at Shahbag are bloated with rickshaws, scooters, cars and trucks. But since February 5, 2013, the two-, three- and four-wheelers have all stepped aside to make room for thousands and thousands of people protesting a verdict from Bangladesh's International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) delivered on that day.

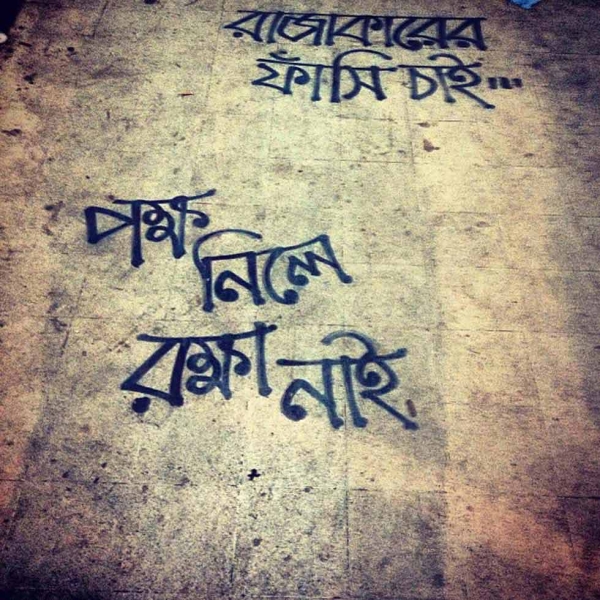

The verdict in question was the life sentence for Abdul Quader Mollah, a politician and war criminal from Bangladesh's Liberation War in 1971. Murder, torture and rape were among the many atrocities Mollah was tried for and found guilty. But after the trial, when he emerged from the court with a smile on his face, flashing the victory sign, 42 years of pent-up emotions came to the surface for the people of Bangladesh. And surprisingly, it was a younger generation, often described as apathetic, that took to the streets and began the protest in Shahbag. Their demand? Hang Abdul Quader Mollah.

On February 14, as thousands and thousands of people joined a candlelit march in Dhaka, Asia Blog reached out to freelance writer Hana Shams Ahmed and the Regional Editor for South Asia for Global Voices Online who goes by the name Rezwan to understand the history and evolution of this protest and get some inside perspective.

Ahmed was an Asia Society Asia 21 Young Leader Delegate from Bangladesh in 2008. In addition, she was previously a feature writer for the Bangladeshi Daily Star and has written about Bangladeshi migrant workers, the legal limbo of camp-based Urdu-speaking minorities, sexual harassment, the abuse of domestic workers, medical negligence at private hospitals, indigenous women's rights, and more.

Dhaka native Rezwan has been blogging at The 3rd world view since 2003. He has been bridgeblogging the Bangladeshi and South Asian blogosphere in Global Voices since 2005 and is also the translator-coordinator for the Global Voices Bangla Lingua.

Can you explain to our readership what the Shahbag protest is, and how it got started?

Rezwan: During the 1971 Liberation War an estimated three million people were killed by the Pakistani army and approximately 300,000 women were raped. Local political and religious militia groups like Razakar, Al Badr and Al-Shams, many of whom were also members of Jamaat-e-Islami, aided Pakistani soldiers in mass killing, particularly targeting Hindus. They also resorted to rape, arson and many other crimes against humanity. Jamaat-e-Islami sided with Pakistan and did their best to deter Bangladesh's independence. Even after Bangladesh came into being, Jamaat Islami leaders, many in exile, carried out lobbying in the Middle East not to acknowledge Bangladesh.

After the war, as many people were under trial and many were absconding, Jamaat-e-Islami was virtually non-existent. In 1974 head of state Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared a mass amnesty for many detained — those who did not have sufficient charges or lack of evidence [against them]. But the clemency was not for those who were involved in mass murder and other grave crimes against humanity. Still, hundreds of people were in jail for the charges. In 1975 Sheikh Mujib was assassinated. And the subsequent governments reinstated Jamaat-e-Islami by amending laws who in the 1991 was in the coalition government with Bangladesh Nationalist Party (now in opposition). During the mid-2000s Bangladesh encountered a surge in militancy. Reports said that Jamaat-e-Islami patronized like-minded Islamists to build many training camps in madrassas in remote Bangladesh. When in 2009 the Awami League government came into power they had an election mandate to implement trials of war criminals. The ICT was established and laws were enacted to pave the way to the much-awaited war crimes trials.

Long before it was Awami League's mandate, bloggers and online activists were raising their voices (since 2006) for the trial of war criminals. They even launched a mass signature campaign in 2008 to pressure political parties to provide roadways for the trial.

On February 5, 2013, Abdul Quader Mollah, the secretary general of Bangladesh's Islamist party Jamaat-e Islami, was sentenced to life in prison for murder, rape, torture and other crimes committed during the 1971 Liberation War. But tens of thousands feel that justice has not been served. They want him hanged.

The Bloggers and Online Activists Network (BOAN) created a Facebook event to invite people to occupy Shahbagh Square, protest against the strike [Jamaat-e-Islami] called by and demand the death penalty for Mollah. More than 100,000 people were invited to the event and more than 10,000 people confirmed they were joining. That started the protest and it grew day by day as more people joined spontaneously.

Hana Shams Ahmed: The expectation from these trials was that all those who were marked war criminals would be handed over with the maximum penalty allowed by the law of the land — which is the death penalty. When Quader Mollah, one of the known war criminals, was given a lesser penalty, a life sentence, people began to smell foul play in the trial process, that the government may have carried out a back-door deal in the judicial process. This brought the people down on the streets in droves to protest against the verdict against Quader Mollah.

What particularly about this war criminal, Abdul Quader Mollah, and this case, drew so many people from all walks of life to unite?

Rezwan: The first verdict of the ICT was against Abul Kalam Azad, also known as "Bachchu Razakar," who was sentenced to death for his involvement in crimes against humanity in 1971. Quader Mollah, also known as "Koshai" (Butcher) to the Bengalis in Dhaka's Mirpur area, was a senior leader of the Razakar force. He led many mass murders in Mirpur.

There were six indictments against Quader Mollah. The trial has proven his association in three of these and direct involvement in two killings. He was acquitted on one charge. The indictments are related to the following incidents:

- April 5, 1971: On Mollah's instructions, one of his aides named Akhter killed Pallab, a student of Bangla College.

- March 27, 1971: Mollah and his aides murdered pro-liberation poet Meherun Nesa, her mother and two brothers at their home at Mirpur of Dhaka.

- March 29, 1971: Mollah, accompanied by Al-Badr, Razakars and non-Bangla speaking Bihari men, apprehended journalist Khondoker Abu Taleb and brought him to a place known as Mirpur Jallad Khana Pump House and slit his throat.

- November 25, 1971: An organized attack and indiscriminate shooting by Mollah and his cohorts killed hundreds of unarmed people of Khanbari and Ghatar Char villages in Keraniganj.

- April 24, 1971: Mollah led Pakistan army men and around 50 non-Bangla speaking Biharis into an attack on unarmed people of Alubdi village in Mirpur that left 344 people killed.

- March 26, 1971: He and his associates went the home of Hazrat Ali Laskar and killed his wife, two daughters and two-year-old son. One of his minor daughters was raped before she died.

Ahmed: Azad is absconding from the country. He was given the death sentence in the very first verdict. Quader Mollah is believed to have been a mastermind of massacres, rapes and inhumane crimes during 1971. He was given a lesser sentence and when he came out of the court room he showed the "V" sign with his fingers, denoting victory. It seemed audacious that a person who had just received a life sentence in crimes against humanity came out of the court room expressing victory. People believed that the reason Mollah saw this as a victory was because he knew that under the corrupt political system that exists in the country, if the BNP-Jamaat alliance came to power, he would be pardoned.

But I think this rage is more than just about Quader Mollah himself. This rage is against the impunity that war criminals have been enjoying for the last 42 years. It is about how known war criminals have been socially and politically established in this country and are in a position to be peoples' leaders. The very people who opposed the formation of the country have been enjoying leadership positions. This rage is also towards religious politics that many people oppose in this country.

What role, if any, did social media play in this?

Ahmed: Social media, especially Facebook, played a very important role in initially mobilizing people for Shahbag. Although once the crowd assembled there, people who were not connected to the social media also started pouring in. Social media continues to play a big role in disseminating the everyday news to the people. Now we see bloggers are spending nights at Shahbag with their laptops and multimedia equipment — blogging news instantly, uploading photos, live-streaming speeches, etc. Social media also helped in building emotions and solidarity among people. The images coming out of Shahbag — of men, women and children chanting slogans, lighting candles — are quite powerful. I know of a Bangladeshi journalist who is working overseas at the moment. Her brother told me that she's rushing over to Dhaka for a week, "because she can't take it anymore," and wants to experience the Shahbag phenomenon firsthand.

Rezwan: Social media has been very influential regarding building an awareness for the trials which were delayed for 42 years. It may be mentioned Jamaat has been very accomplished and influential in campaigns and lobbying to free their leaders. They were engaged in smear campaigns since 2006 to decriminalize them and to distort the history of 1971 liberation war and the role of Jamaat during that time. They even had the audacity to claim there were no war crimes, which are already established through thousands of media stories from around the world, U.S. embassy documents, eyewitness accounts, books, journals, video footage, etc. There is actually an active cyber-debate between the anti-war criminal vs. the Jamaat supporters (there are claims that Jamaat recruited cyber-warriors to promote their cause). Even now, at this crucial juncture, you will see many Jamaat supporters are trying to disgrace the Shahbag protests.

Why are protestors pushing for capital punishment?

Rezwan: I know capital punishment is seen negatively in many countries. Bangladesh is one of the 58 countries (66% of the world's population) where capital punishment is still practiced. Whenever there is a talk of strict punishment, capital punishment is sought. For example, now violence against women via acid throwing or carrying drugs may get one a death penalty. Whether or not that should be abolished in the country is another debate and requires a mass awareness campaign for the Bangladeshis, of whom 40% cannot read and write. For them till now capital punishment for the evil is very much civil. People have taken to the streets demanding that Mollah and other war criminals be put to death, fearing that if they are imprisoned, they may be released after a regime change. The opposition BNP is opposing the trial as one of their leaders (he is known in the locality as war criminal) is also under trial. The next election is due in less than a year's time.

When Abdul Quader Mollah emerged from the supreme court on the afternoon of Tuesday, February 4, he turned to the press waiting outside, smiled, and made a victory sign. This is an odd reaction for a man just sentenced to life in prison considering the list of charges against him. And people know that he will not remain in jail for long and justice will not be served.

Considering all, the protesters want a closure of the 1971 crimes by demanding the death penalty.

Ahmed: The protestors believe that the war criminals will be able to get out of jail if they don't get capital punishment. Also, in Bangladesh there has never been a movement against capital punishment. People are still not sure what stand to take regarding capital punishment. Even human rights activists have mentioned that although they are against capital punishment in general, the war crimes trial is a very emotional issue for them and they want the war criminals to be handed over with the maximum punishment that the law of the land allows.

People also do not have faith in the system and in their politicians. They have seen that even the supposedly secular Awami League party has formed alliances with Islamic political parties. Sheikh Hasina was part of the anti-autocrat movement in 1990 which saw the fall of President Ershad, but later formed an alliance with the same Ershad in order to win electoral votes. These self-contradicting alliances and ingrained corruption within the system make people uncomfortable about asking for anything less than capital punishment.

How do people who support the cause but are against capital punishment fit into the broader dialogue?

Rezwan: There are some like me who do not support capital punishment for normal crimes. But genocide and mass murder is a different ball game. The hatred against Bengalis shown by Jamaat and its cohorts in 1971 isn't normal crime. So they deserve the death penalty. It's actually our Nuremberg moment. You can find some voices who are against capital punishment even for war criminals. Those pushing for the death penalty are only trying to campaign for the cause — not imposing it on those who differ.

Ahmed: This is the problematic part — the images of little children with "fashi chai" (we want death by hanging) written with red paint on their cheeks and their bare torsos, the chanting of slogans using violent language like "Ekta ekta Shibir dhor, dhoira dhoira jobai kor" (Take one Shibir at a time and behead them). There is an element of revenge embedded in the protest language and images.

The other problematic part is that there is not enough demand from Shahbag about due process in the trials. Many journalists/activists who have been following the trials have pointed out that the trials were not following due process — including the disparity in the number of witnesses allowed for the defense and the prosecution and disappearance of a key witness, among other things.

There is a small group of people who are actually seeking justice from the courts, and don't want the death penalty and there are some others who are careful about speaking about these things, fearing getting labeled Jamaat sympathizers. Many of the protestors have been intolerant towards any criticism of the movement, saying, "Either you are with us, or you are Jamaat supporters." It has become almost impossible to speak about the movement in a nuanced way. No one wants to be labeled a "rajakar," yet there are many who fully support the cause but don't support capital punishment. They have been left in an uncomfortable position about how to address the whole issue and the violence and revenge exhibited by the protestors. To set a precedent, it's important that the whole process is transparent and fair, so that history does not look back upon these trials and find prejudice in the trial process.

As protests continue in Dhaka, we want to know your perspective on the Shahbag protest. Please share your thoughts in the comments below.