China's Elusive Search for Innovation

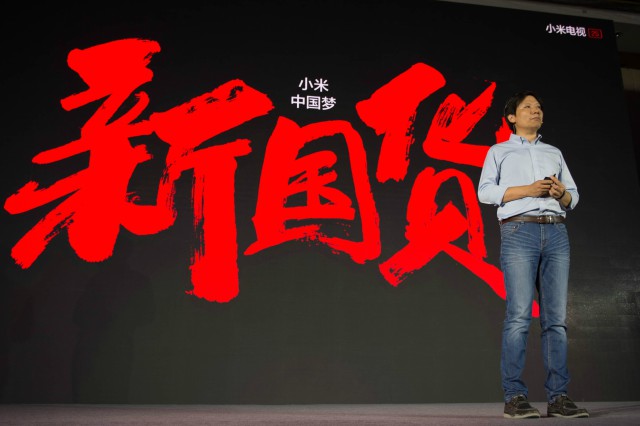

Lei Jun, popularly known as China's "Steve Jobs", is one of the world's most influential telecommunications executives. (Getty Images)

Over the last three decades, as China’s once-impoverished economy emerged into the world’s second-largest, the country has still failed to shed one aspect of its international reputation: that it can’t innovate. In January, former Hewlett Packard CEO and current Republican presidential candidate Carly Fiorina told an Iowa blogger: “I’ve been doing business in China for decades, and I will tell you that yeah, the Chinese can take a test, but what they can’t do is innovate.”

Fiorina’s comments may be typical for an American populist attempting to win a presidential primary. But her sentiments are commonly shared in China itself, where the country’s perceived lack of innovation is a genuine national concern. In a 2013 post published on Zhihu, China’s Quora, and translated by Foreign Policy, an anonymous Chinese blogger wrote that the country “lacked an environment conducive to creativity” and that Chinese people are “not good at using lively debate to turn a spark of originality into a developed idea.”

In assessing this innovation gap, critics, both domestic and foreign, pin the blame on a number of factors. There’s an education system that encourages rote memorization, a corporate culture that penalizes risk taking, and a government that controls the flow of information. Under the administration of Xi Jinping, China’s president, these problems remain as daunting as ever. But there are signs that a culture of innovation is taking hold.

Take Xiaomi. The cell phone manufacturer — whose name means “small rice” in Chinese — has become the darling of China’s tech scene, emerging as the world’s third largest cellphone company and accruing a valuation of $46 billion. The company’s success has turned its founder Lei Jun — whom Asia Society named an Asia Game Changer in 2015 — into a celebrity whose slender frame and taste for t-shirts and blue jeans evokes comparisons to the late Apple CEO Steve Jobs. Xiaomi, however, is no Apple imitator. The company’s smartphones are a fraction of the cost of iPhones, putting them within reach of China’s burgeoning middle class. Now, Lei Jun is betting that his formula will work in other emerging markets. Last week, Xiaomi announced that it would expand into Africa.

The success of Xiaomi and other large tech firms like Tencent and Alibaba validate, in part, the effort of the Chinese Communist Party to promote and foster innovation. The government now sets aside $163 billion for research and development, and China now leads the world in patent applications. According to Kaiser Kuo, director of international communications at Baidu and a frequent commenter on China’s high-tech sector, China has “wisely invested in telecommunications infrastructure and created the competitive conditions to ensure basic services are affordable and accessible.”

For all this success, several obstacles remain for China to realize its innovative potential. Some of these are structural. According to Kuo, China’s enduring abundance of low-cost workers, spurred by internal migration from the countryside to cities, has reduced one primary incentive to innovate: saving labor costs. Combined with comparatively low-risk business opportunities that still abound in China’s economy, private investors have little reason to gamble on ventures that may not work; those that, in more mature economies, tend to foster innovation.

Then there’s China’s education system, one which, in many respects, has changed little in centuries. In order to determine which college they attend, China’s high school students must take the gaokao, a nation-wide entrance examination that largely functions as an exercise in fact recitation.

“The gaokao fosters a culture whereby students are rewarded for their ability to plagiarize the content of teachers and materials and are punished for learning anything outside of [them],” said Rich Brubaker, the managing director of collective responsibility at the China Europe International Business School and an expert on Chinese innovation.

Many of China’s elite students attend universities elsewhere, and, following their graduation, remain overseas to pursue their professional careers. For those who do not leave, incentives to advance through shortcuts and outright fraud remain.

According to Brubaker, there are signs that China is tackling this problem. Increasing numbers of affluent Chinese students who remain in the country choose to attend private primary and secondary schools that favor a more holistic approach to education, and this, combined with advancements in new sectors such as mobile technology, make him optimistic about the future.

“Over the next five to 10 years, I think there will be a lot of advancements made by Chinese entrepreneurs and firms,” he said. “There is a lot of money sloshing around, the culture around being a startup entrepreneur is changing, and the market needs are huge.”