Testing Times for ASEAN as Indo-Pacific Leaders Meet

by Richard Maude, Asia Society Australia Executive Director, Policy, and Asia Society Policy Institute Senior Fellow

The annual ASEAN “summit season” is upon us. What’s on the agenda?

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) begins three days of intense regional summitry on 26 October, facing a barrage of tests to its relevance, internal cohesion, and social and economic health.

Chaired by Brunei, Southeast Asian leaders will meet virtually for their end-of-year summit and a suite of meetings that have ASEAN at their core. Most significant of these is the annual leaders’ meeting of the 18-member East Asia Summit (EAS — China traditionally is represented by its premier).

ASEAN leaders will also hold “plus one” meetings with their biggest dialogue partners — China, the United States, India, Japan, Australia, and the Republic of Korea (ROK) — along with a “plus three” summit with China, Japan and the ROK.

The ASEAN summit — the group’s highest policy-making body — and its associated meetings are big affairs. They produce an astonishing quantity of often immensely long declarations, statements, frameworks and plans to support the ASEAN community-building project.

Each chair brings its own priorities and projects to the table. This year, for example, Brunei’s “deliverables” include an ASEAN declaration on upholding multilateralism and a “blue economy” initiative.

Every summit season also has its share of dramas and small battles. There will be particular interest this year in how President Joe Biden approaches the EAS and the “plus one” summit with ASEAN. Biden has yet to engage bilaterally with a single Southeast Asian leader, so ASEAN will be looking for reassurance both about his Administration’s commitment to the region and U.S. willingness to manage competition with China.

The positioning of leaders on intractable flashpoints such as the South China Sea and North Korea, will be watched closely. The EAS could also be another important platform from which to further internationalise rising concerns about China’s coercive pressure on Taiwan, although Beijing will fight tooth and nail to keep any references to cross-strait tensions out of the chair’s statement.

In 2021, though, it is three other major challenges that are most influencing the summits.

First, geopolitics is catching up with ASEAN as the United States and its allies and close partners intensify efforts to balance China’s power. Second, ASEAN’s efforts to deal with the coup and subsequent crisis in Myanmar have foundered. And, third, ASEAN wants all the external help it can get as it grapples with the deadly Delta variant and charts a course for economic recovery.

Central, but less relevant?

ASEAN anxiety about its “centrality” to economic, political and security cooperation and dialogue in the Indo-Pacific is rising as U.S.-China competition intensifies.

The new AUKUS partnership has been a sharp and — for some, especially Indonesia and Malaysia — unwelcome reminder of the new era.

AUKUS reverberates still through the region. Southeast Asia understands the new partnership is but one part of a much larger dynamic. The United States’ alliances with Australia and Japan are increasingly positioned as bulwarks against Chinese military aggression, while the Quad countries seek through both hard and soft power to balance China and build a multi-polar regional order safe for democracies.

ASEAN’s anxieties are threefold — of being caught up in a conflict, of being forced to “pick a side”, and of being sidelined: central but no longer relevant to the most pressing challenge of the age.

But ASEAN was not built to manage major power competition and should not expect to do so. Instead, the task for ASEAN is to find a productive co-existence with new groups like the Quad.

This is both possible and necessary. The Quad is here to stay, but its members all recognise the importance of a strong ASEAN and the value of its more inclusive regional architecture and norm-building and regional economic integration agendas.

For its part, ASEAN must accept the right of the Quad countries to make their own choices about China’s rise — to protect their sovereignty and respond to genuine concerns about China’s assertive foreign policy and massive military modernisation. This means a tougher, tenser region. ASEAN has no choice but to adapt.

Some in Southeast Asia are quietly supportive of efforts to sustain a military balance in the region. Others instinctively point the finger of blame at everyone but China for disturbing the peace, underlining how conditioned ASEAN has become to avoiding even the mildest of public criticism of Beijing.

This is not what “not picking sides” looks like. ASEAN has more agency with Beijing than it thinks: it should use it.

In return, it is reasonable for Southeast Asia to call, as Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan did recently, for the United States and China to manage their competition responsibly and for external powers to engage the region “on our merits, rather than be seen purely through the lens of the U.S.-China competition”.

ASEAN as whole is not yet convinced the Biden Administration is listening. Indonesia in particular feels neglected. Still, the Quad seeks to answer the region’s call, with its strong emphasis on contributing to public goods, especially in fighting the pandemic and supplying vaccines.

Quad countries also already make significant contributions to projects and initiatives carried forward under one ASEAN banner or another, like infrastructure, smart cities, and management of the Mekong.

The four nations could further demonstrate their ASEAN credentials by doing more to give life to the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, an Indonesian-led initiative to reinforce norms of peaceful behaviour in the region and encourage cooperation on issues such as sustainable development and connectivity.

Myanmar: ASEAN’s unsolvable crisis

While beset by external challenges, ASEAN is also grappling with an internal threat to its cohesion and effectiveness: the humanitarian and human rights disaster that is post-coup Myanmar.

An ASEAN leaders’ meeting in April agreed on a “five point consensus” to deal with the crisis: an immediate cessation of violence; dialogue “among all parties ... to seek a peaceful solution”; appointment of an ASEAN chair’s special envoy to help mediate such a dialogue; a visit by the special envoy; and, provision of humanitarian assistance.

ASEAN could not reach consensus on a special envoy candidate until early August, when Brunei’s Second Minister for Foreign Affairs, Erywan Yusof, was appointed. In September, ASEAN donated $US1.1m worth of medical supplies and equipment to the Myanmar Red Cross Society, a first batch of the planned humanitarian assistance.

But the junta has blocked any progress on the more substantive elements of the five-point plan, including by placing unacceptable conditions on Erywan’s visit.

Frustration with the military’s obduracy boiled over at an emergency meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers on 15 October. Faced with the unedifying prospect of coup leader Min Aung Hlaing sitting down with ASEAN and Indo-Pacific leaders at the summits, ASEAN effectively disinvited him, opting instead for a “non-political” representative.

Putting aside questions as to how ASEAN will identify a “non-political” leader to sit in Myanmar’s chair, this is a rare and significant step. The junta’s sharp response, disingenuously accusing ASEAN of acting against the principles of the ASEAN charter and weakening the group’s “unity” at a time of strategic competition, suggest it thought ASEAN wouldn’t dare.

Still, welcome as this move is, the obstacles to ASEAN’s five-point plan look insurmountable. Myanmar’s military rulers began backtracking from the “consensus” before the ink was dry. The junta has no interest in real dialogue nor in any “solution” that does not entrench its rule. The military believes it can grind the opposition down and the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) has in turn declared a “people’s war” against the regime. There is no space here for compromise.

The very nature of ASEAN places limits on the pressure it can apply. The military regime has trampled brutally all over solemn commitments in the ASEAN Charter to human rights and democracy. But these commitments play second fiddle to the priority ASEAN places on non-interference in internal affairs.

ASEAN is divided over just how hard to press. Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, in particular, see a ‘”stern test” of ASEAN’s credibility. Others worry about ASEAN unity and want to keep lines of engagement open. The divide is at once between the more democratic and autocratic members of ASEAN and between maritime and mainland Southeast Asia.

ASEAN’s Myanmar challenge has prompted calls for the group to find a “new modality” to deal with crises and for its Charter to be amended. ASEAN has circled inconclusively around such proposals in the past, in particular the idea that the “ASEAN minus X” model, which already applies in the economic sphere, could be extended to allow a subset of the group to take action on major crises like the one in Myanmar. But with so much on ASEAN’s plate there appears little will or bandwidth in the group to take on contentious reforms.

Meanwhile, in Myanmar the bloody conflict and the suffering roll on. ASEAN’s partners, who have found it convenient to line up behind the five-point plan and keep the problem largely in ASEAN’s court, should not let themselves off the hook.

Some, like Australia, have scope to toughen targeted sanctions on the military. Partners must continue to demand the release of political prisoners. And there is an urgent need for more humanitarian and pandemic assistance, despite the immense challenge of delivering this in a conflict zone. Finally, ASEAN still has tools it could be encouraged to use, like the suspension of Myanmar’s membership, to leverage concessions with humanitarian outcomes.

The pandemic and economic recovery

Controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccinating its populations, and supporting economic recovery are ASEANs highest priorities and will feature prominently at the summits.

The renewed ferocity of the pandemic in Southeast Asia through 2021 has slowed the region’s fragile and uneven economic recovery. Both the World Bank and International Monetary Fund have downgraded their growth forecasts for the region.

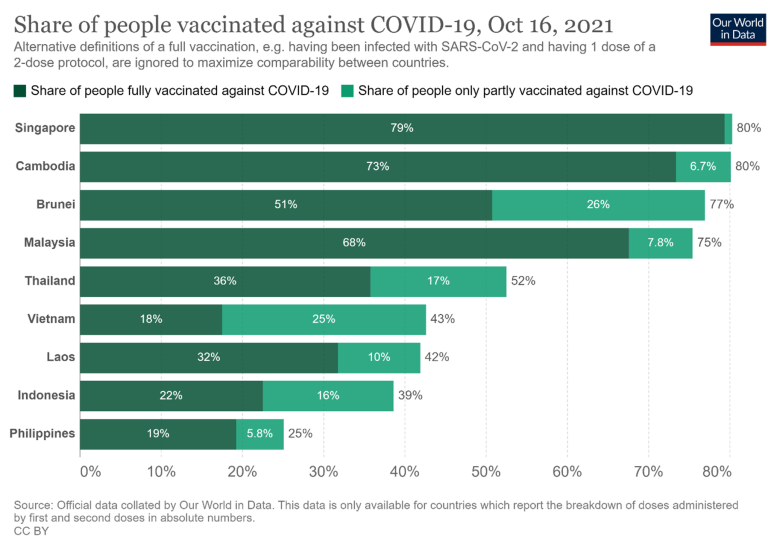

Vaccine inequality is a major cause of the slowness of Southeast Asia’s economic recovery compared to most advanced economies. The vaccine supply picture is changing, as wealthy countries donate excess stocks and production ramps up (including within Southeast Asia). New vaccines are in the pipeline. But Southeast Asian nations such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Laos, and Vietnam still have a long way to go to reach high levels of national vaccination.

ASEAN’s partners have already given financial support to a new COVID response fund and a yet-to-be-established ASEAN Centre for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases. But ASEAN has a slew of other pandemic and economic recovery-related needs. Donations of additional vaccines will be welcomed. The group wants to beef up its laboratory capacity across the region to improve its ability to conduct genomic testing and surveillance. ASEAN countries are interested in vaccine production opportunities, including for mRNA vaccines.

Desperate to re-start tourism and business travel, ASEAN countries are also beginning to open up quarantine-free travel lanes for fully-vaccinated arrivals from selected countries, with Singapore leading the way. ASEAN will be looking to partner countries to help bring visitors back to the region.

Rapid testing kits will help the poorer Southeast Asian countries manage quarantine-free travel. “Vaccine discrimination” is also a red-hot issue for most ASEANs, especially Indonesia, which has relied heavily on Sinovac shots. So ASEAN wants partner countries to recognise China’s vaccines for overseas travel, as Australia has done, for example.

ASEAN in 2022

At least some ASEAN countries, along with partners like the United States, Australia and Japan, will look to 2022 with some trepidation, as Cambodia assumes the chair.

Cambodia’s Hun Sen government has hewed ever closer to China in recent years. And when Cambodia last helmed ASEAN, in 2012, its backing of China’s position on the South China Sea created the group’s most serious split in decades.

Now, in an even more testing period, Cambodia’s role as chair will be watched closely. Other ASEAN countries won’t want a repeat of the 2012 split on South China Sea language. Nor will they want Cambodia to undermine the position of Southeast Asian claimant states in the long-running negotiations with China on a South China Sea code of conduct.

Similarly, Cambodia’s authoritarian government is very unlikely to push Myanmar’s military leaders on the five-point plan (or on anything, really), nor to tackle China on Mekong River issues.

U.S. officials are already seeking to shape Cambodia’s approach, making clear they expect Phnom Penh to “play a constructive role in addressing … political and security challenges”.

Cambodia probably doesn’t want to rock the boat in such a challenging period for ASEAN. But much depends on how hard China presses its interests. At best, Cambodia’s year as chair looms as a lost opportunity for ASEAN as it seeks to navigate turbulent times and bolster its effectiveness and credibility.

Richard Maude is Executive Director, Policy at Asia Society Australia, and a Senior Fellow at Asia Society Policy Institute.

Asia Society Australia acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government.