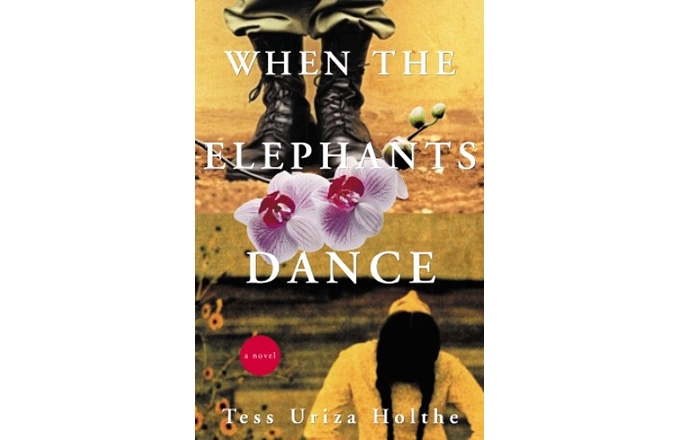

When the Elephants Dance

Tess Uriza Holthe is a Filipina-American writer from San Francisco. Her first novel, When the Elephants Dance, is inspired in part by her father's experiences growing up in the Philippines during World War II. The novel recounts supernatural tales based on indigenous Filipino mythology and Spanish-influenced legends as told by an extended family hiding in a cellar during the last week of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Alternating between the gruesome realities of torture, starvation and rape brought on by the war and the magical realism of Filipino folklore, When the Elephants Dance presents a lyrical, multi-layered view of the history and culture of a war-torn nation. It has been called "a remakably rich story... [with] a well-orchestrated chorus of voices" by Kirkus Reviews and "an impressive debut" by Library Journal. Asia Society spoke with the author from her home in northern California.

Can you explain the title of When the Elephants Dance?

It’s from an expression I found in some of the research I did on Robert Lapham, one of the American guerillas in the Philippines during World War II. They used to say, “When the elephants dance, it isn’t safe for the chickens.” The elephants were the Americans and Japanese who were fighting then and the chickens were the Filipino civilians that had to get out of their way or get crushed. I think it was a saying that originated prior to World War II, but they applied it to that time period.

How much of this novel is based on family stories and how much is fiction?

All of it is made up, but a portion of the [Karanalan] family story was based on my family stories. The story about the church that sank into the ground was based on a family story. I had heard growing up that there was a church in Manila that sank into the ground and only about a third of the door was above ground. My family explained to me that in that town the people were really arrogant and an angel came in the form of a dog to test the arrogance of the village's parishioners. They all scoffed at the dog and the dog brushed its paws on the church and the church sunk underground. Another explanation is that the church sunk during an earthquake, but I based the section of the novel about Esmerelda on the legend of the dog. So there were little pieces of stories my family told me that went in the novel.

The story about the fisherman and the bone is also based on one of my father’s stories. My father used to be an errand boy for a neighbor who was rumored to be a magical fisherman. As the neighbor was dying, his wife called my father over and told him that her husband wanted to give him something. When my father arrived, the neighbor took this fishbone out of his mouth and tried to give it to my father. My father was only nine and he didn’t want the fishbone, so the neighbor threw it out of the window. Supposedly a huge storm started the moment he threw the bone, like he was letting go of this giant power. I based the story of Mang Minno and the fishermen in the book on that story my father had told me.

I had also heard so many ghost stories growing up that I wanted to intertwine them within the rest of the novel.

In addition to the supernatural stories, did your family tell you stories about their experiences during WWII even though they were painful?

Yes, we just heard some new ones this weekend from my father. My relatives tell stories from the war repeatedly, which I thought everyone’s family did, but people tell me that they are amazed that my family was so open about it and that their families wouldn’t talk about it. One woman I spoke to at a reading told me that her father would only mention that he met the Emperor of Japan, but wouldn’t say anything else [about the Japanese occupation]. I think with my family, telling these stories was a healing process.

Has your family read the novel?

No, my family is one of storytellers, but not readers. I had to actually tell them what was in the book. My parents don’t read except for the news. I don’t know if my Dad will ever read the book. We were joking that when it becomes a book on tape, then maybe he will pick it up. They are very proud of it, but they haven’t read it.

How did you go about doing historical research for this book? Are there many historical accounts of the Philippines during WWII?

Yes, there are a lot of books and articles, but mainly I relied on historical novels. I went to any library I could find for research, but I really had the meat of it already from my family. I just needed the dates and then added information regarding General [Douglas] MacArthur.

Have you ever been to the Philippines?

No, I’ve never been to the Philippines, though I've heard about it all my life. My family would describe the heat, the scents, the fruits, the animals, the bugs, the terrain, and my millions of cousins. Growing up, I couldn't afford to visit, and then during college I was working just to put myself through. I would love to visit in the near future, but with my schedule lately it may be a year or two before I can. My sister is actually going back this Friday and she would have been the ideal person to go with, only I have been blessed with more Bay Area readings and signings for the book so I can't go with her.

Your novel showed various layers of Filipino culture, particularly the interaction between indigenous Filipino religion and Catholicism. Does this type of syncretism characterize the religion you grew up with?

It characterized our household and I would venture to guess it does for most Filipino households. There is the belief in God and then there are these dwarves and other [supernatural creatures]. I’ve encountered it in just about every Filipino family I knew growing up.

Filipinos never let go of how they respected the forest. My father would always say, “Watch out for the dwarves [in the forest]. You can crush their homes.” And even now, when I go hiking in Marin where I live, I say in my head, “Excuse me, I’m sorry,” sometimes, just to warn [the dwarves]. It’s a habit and I think a lot of people have that mix of superstition and Catholicism and believe in them hand in hand. Maybe people are in denial of how the two [traditions] conflict.

When the Elephants Dance depicts a world inhabited with supernatural creatures like elves and ghosts, and contrasts it to the stark realities of war and death that pervade the novel. Why did you intersperse these fantastical myths and legends with the grim stories of war?

There are two reasons. First, it was organic because I grew up hearing both [types of stories] side by side and they made sense. I didn’t see the [mythical stories] as anything different. Consciously I knew the war was so horrific and I wanted something as a relief in between the war stories. But then I found myself building the conflict in the mythical scenes as well. I knew that the war was tough to consume, so I interspersed the [mythical scenes with the war scenes].

As gruesome as the war scenes are, I thought When the Elephants Dance was ultimately uplifting in that many of the characters emerge relatively unscathed given the horrors they have just experienced.

I have been getting different reactions to [the survival of some of the characters] at the ending of the book. My father survived and went on to live a full life. I spoke to a woman yesterday whose mother didn’t make it out of the war, so for some people there really are no endings to tie it all together.

You used Tagalog and Spanish in many of the dialogues in the novel, and then translate them in the following text. Why did you decide to include Tagalog and Spanish phrases?

I heard both languages growing up because a lot of Filipino families speak Spanish and because Tagalog was influenced by Spanish during the occupation. I read All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy and he interspersed Spanish throughout the whole thing, but he doesn’t translate it. I realize how much including the Spanish colored his novel. The characters became authentic to me. Also, I had never seen Tagalog in print anywhere and I thought it would be a nice addition.

One of the main themes explored in the novel is division and infighting among Filipinos in the face of foreign invaders, be they Spanish, Japanese or American. Given the current political situation in the Philippines with the secessionist movement and the arrival of US troops, do you think this message is particularly relevant today?

Yes, there is definitely an amazing parallel for the civilians who are struggling there. There are people in the Philippines who do not want Americans there because they have been occupied by so many different nations for so many years. There are others who are loyal [to the Americans] and want them there to rid the Philippines of these extremist groups like the Abu Sayyaf. Just like in World War II, there were different factions fighting. During World War II, some Filipinos wanted the Japanese to come in order to be pro-Asian. There were groups that wanted to collaborate with the Americans and not the Japanese. And there were still other groups who didn’t want any [foreigners in their country]. It’s the same right now in the Philippines. As American troops come over to help the Filipino army train to purge the extremist groups, there are Filipinos who feel they are being occupied, even though the Americans are there to support [the Filipino army]. The civilians are probably terrified to have any of this go on. The conflict continues.

How did this novel develop? Have you always been a writer?

I have written journals and read all of my life. The book took a year and a half to write. Two years ago I wasn’t a writer, I was just a controller for a private company here in California. Growing up, I always had creative tendencies, but my folks said I had to be a doctor or lawyer or an accountant, something very practical. It was only after I had my degree and a career that I thought I would take up writing as a hobby. I took a writing class and it hit a vein and this book just came out whole. I think it was ready and I was ready to be a writer, but I just kept depressing it and putting it away in a box.

Who are your influences?

I wish I had read Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things before I wrote this book. I read it because a publicist compared me to Arundhati Roy and I had never read her before. I loved that book and I read it twice. Before that I was influenced by Cormac McCarthy because I loved the dialogue in his books. The dialogue was always lively and never stilted. I love Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. I think the books about family and that have a sense of adventure [have inspired me]. Amy Tan was of course a big influence because it was the first Asian voice I read.

What are you working on next?

I can’t tell you. When I was working on When the Elephants Dance, I had read talking about a novel [before it came out] was like telling a joke. You don’t want to tell it too many times or else it gets stale. Also, when I keep myself from telling people what the next novel is about, it makes me want to write more each night so that I get closer to letting people know.

Interview conducted by Michelle Caswell, Asia Society.