Rohinton Mistry: 'Family Matters,' and Literary Ones

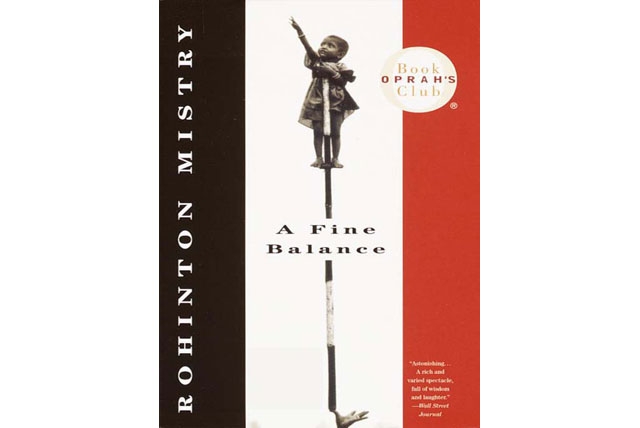

NEW YORK, November 1, 2002 - Rohinton Mistry is the author of A Fine Balance (1995), which won several awards including the Commonwealth Writers Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Fiction, and Such a Long Journey (1991), which won the Governor General's Award and the Commonwealth Writers Prize. Both books were also nominated for the Booker Prize.

Mistry's most recent novel, Family Matters, also nominated for the Booker Prize, was awarded the Kiriyama Prize for fiction. Shortly after the publication of Family Matters, Mistry did a reading at the Asia Society in New York.

Mr Mistry's first work of fiction, Tales from Firozsha Baag, a collection of short stories, was published in 1987.

In this interview, Mistry discusses his initial interest in music and what eventually drew him to writing, as well as the kind of literature he finds most compelling.

As a young adult in India, you were more interested in music than in any other form of artistic creation. What determined the shift from music to literature?

I think it probably has something to do with the act of emigrating; I am speculating, of course, I am not really sure. The music that I used to play - both to make money and to have fun - was Bob Dylan, for example, or Leonard Cohen, or Simon and Garfunkel. I was imitating all these people. I also tried at some point to write my own songs which I eventually realized were not very good, although at the time I thought they were great.

Going to Canada, faced with the reality of earning a living and realizing that although I had, up to that point in my life, read books and listened to music that came from the West, there was a lot more involved in living in the West. I felt very comfortable with the books and the music, but actually living in the West made that same music seem much less relevant. It suddenly brought home to me very clearly the fact that I was imitating something that was not mine, that made no sense in terms of my own life, my own reality.

While I had been in Bombay, the idea of Bob Dylan and protest songs from the 1960s had enormous appeal and of course there were many people in Bombay at the time who were using these protest songs - they were a student specialty in the 1960s and 1970s. One man with a guitar was very powerful, and they were using that model, writing protest songs about the Indian reality, and god knows, there was a lot to protest about.

Once I was living in Toronto, it just didn't seem to work for me anymore. I was a stranger in that culture and to sing these songs back to them would have seemed odd, to say the least. And suddenly I didn't have the energy to pursue music as a career. So I started working in a bank. But reading of course was always a pleasure, and continued to be a pleasure. Listening to music was fine as well, but I just didn't feel like performing anymore. I felt I didn't have an audience whom I could sing to.

I am not quite sure how that transition from music to literature occurred but again I can try to speculate. Because I enjoyed reading, I decided to take evening classes at the university in English literature and philosophy. I thought I would enjoy reading the books and I discovered I also enjoyed very much the writing process, the assignments for the courses, the essays, some of which were quite demanding, were in fact rather long pieces of work. I enjoyed that part the best of all - as much as, and sometimes more than, the actual reading. At some point, I decided it would be fun to write as a career. During my third year in university, there was a short-story competition announced. I wrote a short story for that, prompted mostly by my wife, who had tired of hearing me say, "I wish I could write, I wish I could write." So I decided this was it, I was going to try and write. I wrote my first short story and sent it in and it won first prize.

The same thing happened again the following year. I wrote another story for the competition, although I had been writing in between too. It won again, at which I thought: this is really more than just a fluke and that I ought to think about this seriously especially since I enjoy it so much. People also seemed to like what I was writing, which encouraged me as well. So this is how it all began.

I then got a grant from the Canada Council, the Arts Council, which allowed me to give up my bank job after 10 years.

That must have been a relief.

It was, but it was also a little scary because I was giving up this perfectly decent job without knowing with any certainty what would follow. Of course the work was tedious and boring and everything, but it was a decent job and it paid the rent and bills.

I was interested to hear what you said about music and what it is, initially at least, that prompted you to move towards literature. You felt that you would only have been able to "mimic" Western musical forms, whereas literature offered you something different. What is it about the form of the novel that appeals to you? Presumably one could make similar arguments about the novel, since it is essentially a European form.

Yes, that is quite right. I suppose if I had had the courage to stay with music and work away at it and find a means of expression where I could feel comfortable that it was an honest expression of something, not just mimicry, it could have happened. One of the main problems with music was that I could sit alone in my room and try to compose a song, but at some point I would have to go out and perform it. The exercise simply would not be complete until I had an audience that was listening to me. With a book I could reach completion in utter solitude. I think that may have something to do with it, although I am still speculating.

Also I do think there is something different when you consider the form of the novel on the one hand, and the form of the protest song, for instance, on the other. The protest song is more limited, and I would have had to invent a new form for it to be an honest expression of my reality. The novel is so all-encompassing, so all-embracing, one can throw anything into it and it will probably swim if you do a half-decent job. I cannot recall now who said that the novel was like an old, creaky ship: you can keep loading things into it and as long as you get the ballast right, it will probably float. I tend to agree with that.

You initially wrote short stories, as you said, and they were eventually compiled into an anthology, Tales from Firozsha Baag. Is there something in particular that draws you to the novel more so than the short story, for instance? Do you see yourself returning to the short story at all?

I do, I do. I like both the forms very much, and they each present their own challenges. People who know about these things say that the short story is the most challenging form, much more so than the novel, because of the precision required; sometimes you have to achieve as much as a novel in a much shorter space and period of time. Had I known that it was the most difficult of forms, I probably would not have started with the short story. I think in some ways they are right.

The reason I started with the short story is precisely because my time was limited; I was working full time and going to evening classes. I thought I could handle a short story because I could work on weekends, and try to write, perhaps, five pages per weekend, and then after three weekends, I could have a 15-page short story. I was in accounting at a bank, so these are the sorts of calculations I would make.

And it worked for me. In fact I called in sick one week and made a long weekend out of it; so I had four days, and I finished the first draft of my first short story in those four days. Looking back, it seems incredible.

So I kept plugging away at the short story and by the time I quit the bank, I had written about five short stories. Then I got the grant, left my job, and wrote another six stories which were published as a collection. Later, with more time at my disposal, I thought I would try the novel. I wanted to see if I could stay the distance because a novel requires a different kind of energy and stamina; one has to keep inventing and creating that complete world, one which you can inhabit, and feel is real. That is the kind of novel I write; there are others of course who write quite differently.

Next: "I don't like clever books, I like honest books."

Many critics of your work compare your writing to 19th-century novelists from Dickens to Tolstoy. Would you agree with that characterization? Do you find yourself drawn more to literature of that period?

I enjoy that kind of writing and that period as much as anything else. People often mention Dickens and Tolstoy in connection with my work but it is not as though I have undertaken any special study of their work. The only Dickens I had read till I took night classes in Toronto was in high school; I think we read Oliver Twist and an excerpt from A Christmas Carol. At university, I remember reading Hard Times, Great Expectations, David Copperfield, and I think that was it, really.

I have not undertaken any special study, nor am I particularly drawn to these authors. In fact, if I were to choose my favorites, what I enjoy most, they would probably include some American writers, like Cheever, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and Updike. Of course I do enjoy Chekhov and Turgenev - these 19th-century writers - but I do not have any special attachment to that period. But I'm not an expert in all this so if the critics think my writing is Dickensian or Tolstoyan I will thank them, and say I am flattered.

Would you agree though that at least stylistically your work is, in some ways, more reminiscent of 19th-century literature (for instance, the traditional mode of storytelling, the social realism, the linear narrative, and so on). A lot of contemporary writing tends to be more fragmented, non-linear, etc. Does that writing appeal to you at all?

It appeals to me when I read it but I cannot write like that. I have tried to write like that; for a while I get really involved and enjoy it but then it all starts to feel like a pointless exercise. It is just too clever by half; I don't like clever books, I like honest books. People may take issue with this saying the two are not necessarily incompatible. For me telling the story and being true to your characters is more important than demonstrating your skill with words, all your juggling acts, the high-wire acts, the flying trapeze acts. Some writers perform on the flying trapeze, which is fine, I suppose; you can go to the circus for an evening but you cannot go to the circus every day of your life. It gets too tedious.

Your previous novel, A Fine Balance, had in a sense a broader canvas than Family Matters although in many ways the two are quite similar. Could you comment on this?

So much of this is not conscious. I do know that both these books, for example, started with an image. It was not the idea of writing a big long story with a vast canvas at all; A Fine Balance was going to be a short novel. It started with the image of a woman at a sewing machine. There was this image, and then I decided that my novel was going to be set during the Emergency. So I had that conscious decision and I had the image of the woman at a sewing machine. Later of course I brought in more characters: the two tailors she hires and the student.

This book was going to be narrated in the first person, or if not the first person, at least from the point of view of the student. He was going to be living in that flat and was to observe the interaction of these four people while the Emergency would provide the backdrop.

As I began writing, though, the story grew and I found myself getting interested in other details of the characters' lives: Dina's life and where she had come from, why the tailors were there and where had they come from, and so on. So it all just grew and I was enjoying myself. It seemed to be working as I wrote so I began letting the canvas grow, as it were, letting it expand. I quickly realized that if I continued in this way, it was going to give me a unique chance to tell not just a story set in the city, but also a story about village life. India still lives in its villages (about 70-75 per cent of the population is rural) so this had a particular appeal for me. The novel would give me the chance to write about this student who comes from the North, the foothills of the Himalayas. I had traveled a little bit there, and found myself writing about it. That's how it turned into such a big book.

With Family Matters, the image that started it was the old man with Parkinson's and I think that may have come from a short story I wrote about 10 years ago. This story does not appear in Firozsha Baag; it came out much later. That story, about 15 pages long, narrated in the first person, is about a man in his mid-80s who is slightly paranoid and feels he is being exploited and ill-treated by his family. He has these delusions and lies awake at night and tells his story. I enjoyed that character very much so that is where this image may have come from to write Family Matters.

Family Matters I think has an internal canvas which is as complex as the external canvas of A Fine Balance; that is the only similarity I can perhaps point out. But there are concerns, primarily political ones, which both the books share. If you write about Bombay in the mid-'90s, especially if you give your characters a political consciousness, it is inevitable that they will sit and talk about what is happening in the city, what is appearing in the newspapers.

Despite the fact that you have lived away from Bombay for over 25 years, you depict the city in extraordinarily evocative terms: the splendor, the decay, the restlessness. How is it that you have retained such a vivid sense of a place you left so long ago?

I have never found it difficult. I think I have kept in touch well enough; I go back and visit, I talk to people here who visit there. Now of course air travel, the media, the global village, and the Internet keeps it all within reach. But nothing substitutes for first-hand experience; and I visit often enough to give me what I need.

Though I must say, it is not a conscious process of observing. I have never caught myself consciously observing and making notes. I do not do that. When you have grown up in one place and spent the first 23 years of your life there - that's how old I was when I left - it is almost as though you are never going to be removed from that place. Twenty-three years in the place where you were born, where you spent all your days with great satisfaction and fulfillment - that place never leaves you. All you have to do is keep updating it a little bit at a time. And it works.

Are you working on anything at the moment?

I don't have much time to sit at my desk and work these days, thanks to these book fairs. But I'm always jotting down little ideas and phrases and fragments which may be useful some day.

Interview conducted by Nermeen Shaikh of Asia Society.