Recovering Family Memories, in Pen and Ink

NEW YORK, May 10, 2010 – Through carefully crafted narrative and hand-painted illustrations, author Belle Yang brought four generations of her family to life at the Asia Society, in a program based around her groundbreaking graphic memoir Forget Sorrow: An Ancestral Tale.

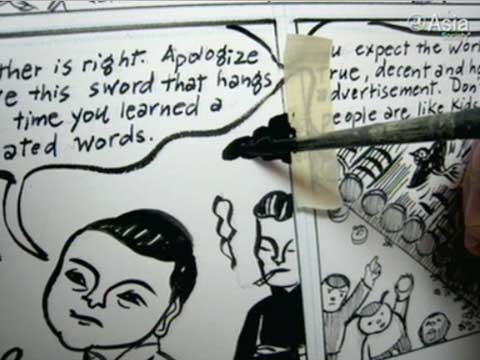

Introducing Yang at the start of the evening, Ken Chen of the Asian American Writer's Workshop (AAWW) stated that Forget Sorrow "reshapes what a graphic novel is." The book, Chen continued, "is what it would be like if a traditional Chinese painter wrote a comic book."

Opening the event, Linda Cai, a high school student from AAWW's Drawing in Color program, shared one of her own comics and spoke about her experience creating comics as a young woman. Then graphic novelist Christine Norrie spoke with Yang about her creative use of the medium and her stylistic choices.

Yang is a classically trained Chinese painter, a trait that makes Forget Sorrow unique within the medium, as she uses a brush to paint her illustrations. "A graphic novel is the perfect balance between words and images," Yang said. With a projection of finished pages from Forget Sorrow on the wall, Yang read some original prose text, demonstrating the editing process that turns prose into a graphic novel.

Yang's father, Baba, escaped to Taiwan from mainland China in 1948, and the author was born in Taiwan in 1960; seven years later the family immigrated to California. "I started losing my cultural heritage," said Yang. "Being Chinese was not fun—there was the cultural baggage of wars, of famine." After college, Yang returned to her parents' home, fleeing an ex-boyfriend turned stalker. Attempting to regain some of her freedom, and start anew, she moved to China to study traditional painting.

Her time in China was colored heavily by her witnessing the rise and suppression of the democracy movement, and she returned home to the United States shortly after the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989. The author compared her relationship with an abusive boyfriend to the Chinese Government's suppression of its people during that time. "I understood violence at a personal level and a societal level."

After returning to California, Yang began to write. "Our stories and voices are what make us individuals .... After returning from China, I valued freedom of speech that much more, and knew I wanted to share my voice." Still living in fear of her ex-boyfriend, she spent a year living with her parents, painting and listening to her father's stories, which would ultimately become the narrative of Forget Sorrow.

As an immigrant raised in the US, Yang found that learning and sharing her family history reconnected her to her Chinese heritage. "Memory to me is like soil, reclaiming the past is like piling up soil—ancestral land—beneath our feet," she told her audience. "I had to rescue great-grandfather’s voice."

Reported by Suzanna Finley