Using Buddhist Values To Navigate Polarizing Politics

Profiles in Buddhism

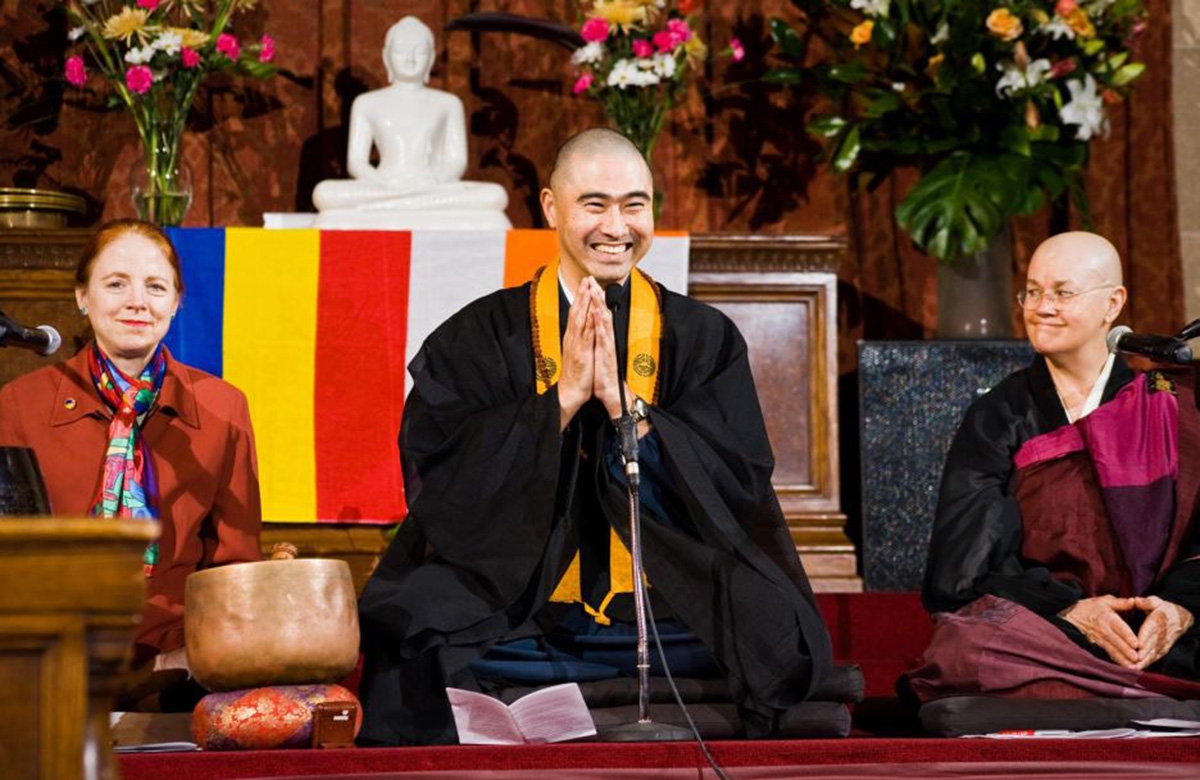

(Image courtesy of TK Nakagaki)

Rev. Dr. T. Kenjitsu Nakagaki is one of New York City’s most prominent Buddhist leaders. Known to many simply as “TK,” Nakagaki has served as a priest in various Buddhist temples all over the world, including his native Japan as well as Seattle and New York, Nakagaki now calls himself a “freelance” priest who has the flexibility to serve the greater New York City community.

During his tenure in New York, Nakagaki has been the president of the Buddhist Council of New York, a Hiroshima Peace Ambassador, a Peace Correspondent of Nagasaki City, Community Clergy Liaison for the NYC Police Department, and former Vice President of the Interfaith Center of New York. He currently is the Founder and President of Heiwa Peace and Reconciliation Foundation of New York, where he continues his work of peacebuilding using Buddhist values. In addition, Nakagaki is also an avid writer and noted Japanese calligrapher. His upcoming book The Buddhist Swastika and Hitler’s Cross: Rescuing a Symbol of Peace from the Forces of Hate uses the infamous symbol to facilitate interfaith conversations and help foster peaceful resolutions across communities.

In an interview with Asia Society, Nakagaki discusses open-mindedness, the rising popularity of Buddhist practices like meditation and yoga, and the value of silence.

What have you found to be the most common misconception the public has about Buddhists and the Buddhist faith?

People are generally still ignorant about the various and sometimes complex traditions of Buddhism, and often don’t distinguish all the different types of the religion. Many people think that Buddhists are all vegetarian, for instance, but even more traditional Theravada monks eat meat. They eat whatever food is offered. Chinese Buddhists are vegetarian, but other traditions are not always so. Buddhists don’t waste food and receive it with gratitude to sustain their life to learn and practice the Dharma.

Buddhism isn’t just about meditation and mindfulness — which is the image that comes to most people’s mind. Yes, meditation is one of the Buddhist Threefold Trainings, but the most important emphasis of Buddhism is cultivating and gaining wisdom.

Additionally, American people tend to believe the Dalai Lama represents all Buddhism. He has been one of the main reasons that Buddhism has been accepted and welcomed in the United States. However, he basically represents Tibetan Buddhist traditions, not other traditions of Buddhism.

I do want to say that since arriving from Japan to the United States in 1985, I have witnessed a significant improvement in people’s understanding of Buddhism. And I expect that people will only continue to enhance their understanding and familiarity with Buddhism in the future.

A significant part of your work is working with interfaith centers to facilitate discussion between other religious groups. Why is fostering conversation and relationships with other parts of the religious community important to you?

Buddhists need to be more involved in our community. Interfaith practices are just one of the ways to bring and introduce Buddhist values and teachings to New York.

My involvement in the interfaith community began when I came to New York in 1994 as a resident minister of the New York Buddhist Church (NYBC). I decided to organize the peace ceremony for the anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings every year for as long as I served at this temple. Though I left the temple in 2010, I continue to organize the Hiroshima and Nagasaki event — this will be my 25th year. In order to do this, I needed to work together with other religions, communities, and professionals. One denomination or one religion alone cannot bring world peace. It felt natural for me to invite interfaith communities to promote it.

Now, my new non-profit organization, the Heiwa Peace and Reconciliation Foundation of New York, represents my commitment to interfaith dialogue. The advisory board includes people who practice various religious traditions, in addition to artists, journalists, and more. In Buddhism, we see it as a world of interconnectedness. We need to work together with mutual respect and mutual understanding — in my head, it’s a literal image of an orchestra of interfaith creating a great harmonious sound together.

My new challenge this year is rather controversial. It’s an awareness campaign of the thousands-year-old swastika — the sacred Buddhist symbol, as well as Hindu and Jain sacred symbol — which was politically damaged by Nazi Germany. The swastika now holds a taboo meaning, and because of that, there is a lot of misinformation that surrounds it. My book The Buddhist Swastika and Hitler’s Cross: Rescuing a Symbol of Peace from the Forces of Hate on this topic comes out later this year. Part of the reason I wrote this book was to prompt another level of interfaith dialogue — when opposite meets, what will happen? The symbol holds totally different meanings and illicit different experiences in Japan versus here in the U.S. For a long time I believed that someone from the Buddhist community needed to write on this matter, so I did.

You’ve called yourself a “Manhattan Monk.” What has made your experience as a practicing Buddhist in New York different from your experiences as a Buddhist minister in other parts of the U.S. and the world?

Diary of a Manhattan Monk is a book I wrote in Japanese about myself and my life running a Buddhist temple in Manhattan. It was written with the intention of introducing Buddhism in New York to Japanese people in Japan. The 16 years that I served at the temple was a time of Dharma experimentation for me. I had so many ideas for programs and activities and I needed to have a place to try them. I appreciate the patience and understanding of the members of the NYBC temple who trusted me to try new things. All of that was such learning experience for me.

My main task was figuring out how to introduce the rich 1,400-year-old Buddhist heritage of Japanese Buddhism to new soil where the understanding of Buddhism only goes back a hundred years. I was given freedom to do new programs which I may not have been able to do in Japan or California where it has already been more established. New York is open to such new things so I feel fortunate to have been able to come to New York. I enjoy learning that various Buddhist Centers offer their unique way to share the Buddha-Dharma in the city — challenging spirits are welcomed here.

What do you think of the mainstream popularization of specific parts of Buddhist practice (like yoga or meditation)? Is there a concern in the community that this may dilute the traditional spiritual meaning of these practices?

I have a confidence that Buddhism has a huge capacity to embrace such a popularized practice of Buddhism. However, I do have some concern about the quality of the teachers. It is my understanding that some have become Buddhist priests instantly without much experience or necessary studies. Buddhist teachers need to be humble, sincere and continue pursuing, learning, and practicing the Buddha-Dharma.

Having said that, it is interesting to see the young energy and enthusiasm from people who are new to the practice. I am sure that this trend has been positive in inviting more people to learn the Buddha-Dharma and experience Buddhist value, which is a good thing.

In a tense and polarizing political climate in the United States, how do you view the role of religion in coping with conflict? Has your faith given you clarity in times of confrontation?

Religions can sometimes become fuel to the flame, but, on most other occasions, religions act more like water to calm down and control the fire. I find that it is somewhat difficult for Buddhists to be involved in polarizing political debates because Buddhist teachings are about the balance, middle path, and non-dualism. If anything, I feel like there is room for Buddhists to get involved more and share their view on issues that are relevant to our society.

I’ve noticed in the U.S. everything has to be black and white, and opposing parties tend not to listen to other views. I feel like the new generation needs to learn the value of listening. The school values sharing, talking, and participation in the class, but they don't place as much value in listening carefully. It’s labeled as lack of participation, but they are in fact participating in the class by listening.

In American society, I notice people need to voice their concerns, otherwise, it’s non-existent. I think this fundamental attitude needs shifting. It is important to hear the voiceless voices which may have more deep issues. Talking has value, but silence in the form of listening should be valued, too. It is interesting to see a new trend in New York emphasizing learning about and caring for mental health and mindfulness. I think these things will help with teaching about listening and being silent. It will be time for the sound of silence.