Meet the Artist: Afruz Amighi

Afruz Amighi in her studio in Brooklyn. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Throughout Asia Society Museum’s exhibition Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians — The Mohammed Afkhami Collection, we are spotlighting participating artists through a series of interviews. Featured in the exhibition, Afruz Amighi is a Brooklyn-based sculptor and installation artist whose installations use a subtle play of light and shadow, often engaging with more complex themes of politics, violence, and displacement.

What does a typical day in your studio look like?

I have a joke with a painter friend of mine. We ask each other, “how’s it going at the studio today, stare at the ceiling much?” Because that's what I do a lot of the time. I take stock of every crack, check out the progress of new cobwebs, you know, routine ceiling research. This can drag on for weeks.

But inertia leads to anxiety, and to ease the anxiety, I’ll work up to the grand effort of turning the music on. Then I’ll make a few sketches. This spirals into notes and Google searches, and all of a sudden I’m launched into the ecstatic beginnings of something new. It’s incredible, but getting there is awful, the ceiling research, that’s my typical studio day.

How do you think art’s role has evolved during the pandemic?

The role of art is to transport, mesmerize, heal, distract. People don’t cast off art in dire times, we lean on it even more.

But during the pandemic, a reliance on social media changed things. A painting or sculpture has aura, the way light hits it, the reflection it casts on the floor, the particles it electrifies in the air, even the smell of fresh paint on the walls behind it in a gallery... without this, it is dead.

And this is true not just for the viewer, but the artist too. There is incredible joy in the act of creation. But art is a form of expression and if it is unseen and not engaged with, it is not fully realized.

How did your upbringing inspire your art?

My mother was a big influence, although she probably wouldn’t see it that way. We never went to art museums. But we were constantly getting our hands dirty, making things. We made gingerbread houses with stained glass windows made from melted candy, easter eggs painted in the most intricate designs, acorn tiaras, and on and on. It was a way of life, and so I just assumed I could continue doing that indefinitely.

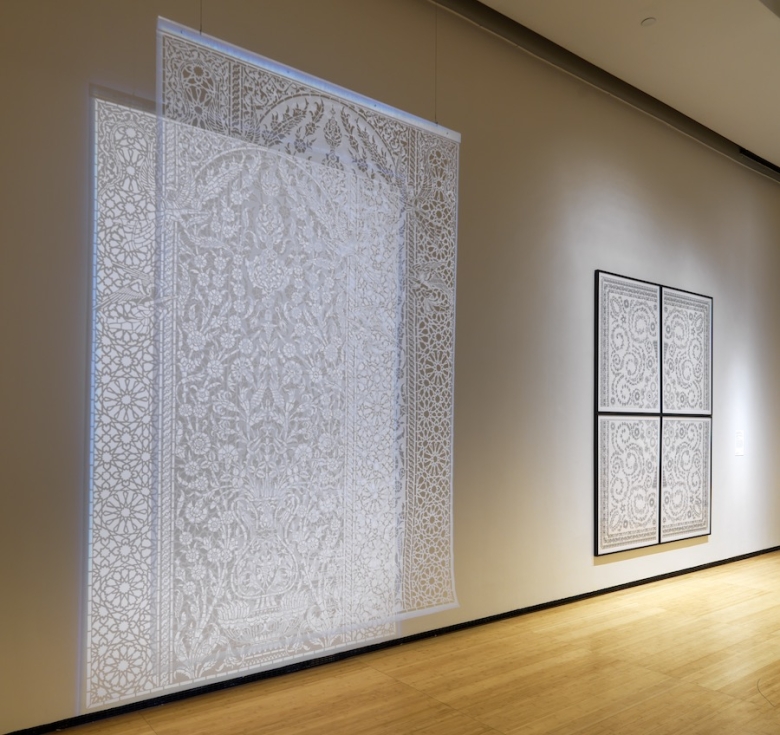

Installation view of Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians—The Mohammed Afkhami Collection. Exhibition runs until May 8, 2022. Foreground: Afruz Amighi, Angels in Combat I, 2010, courtesy of Mohammed Afkhami Foundation. Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2021, courtesy of Asia Society

What themes does your work in Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians — The Mohammed Afkhami Collection focus on?

Angels in Combat was my attempt at forging a meeting ground between heaven and hell. To create this earthly realm, I cut motifs and patterns into polyethylene, a material used by the United Nations to make tents in refugee camps. I wanted to recreate scenes where peace and conflict reign side by side. It made sense to use a material associated with trauma, shelter, displacement, maybe hope at times. In this work, I masquerade violence in Angels’ wings and try to generate tranquility through geometric repetition. There is no clarity here, no heroic answer. My intention was to create a work where people would be confronted with barbarism through imagery and yet could escape it through light and shadow.

Would you describe yourself as a rebel, jester, mystic, or poet? Why?

A poet, with mixed reviews.

Who are other contemporary artists who are capturing your interest right now and why?

The most beautiful shows I saw this year were by Izumi Kato and Wangechi Mutu. Kato made an incredible series of hanging sculptures anchored to the floor with chain, and another series out of pigment on dense stone. Such heavy materials, chain and stone, and yet the work felt weightless, like floating spirits. I saw Mutu’s show at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco where she installed sculptures within their existing collection. She activated the entire museum, awoke it from a centuries old slumber. It was magical and redemptive, such an incredible feeling.

What is an upcoming project of yours or exhibition that you’re involved in that you’re most excited about?

I am developing a project involving the creation of a labyrinth. At this stage I am looking at labyrinths and mazes all over the world, both old and new, made from hedges, marble, concrete, glass, mirror. My hope for now is to find a way to make this labyrinth in an immaterial way, perhaps using light to delineate its pathways.