Books have the power to galvanize. As repositories of memory, history, and ideology, books have inspired social revolutions and been banned by regimes threatened by their contents. Born on the cusp of the Cultural Revolution, Xiaoze Xie has experienced the profound power of books firsthand. “Xiaoze Xie: Objects of Evidence” explores the subjectivity of censorship in relation to the shifting nature of sociopolitical and religious ideologies. Through paintings, installation, photography, and video, the artist traces the history of banned books in China, providing a means to chart changes in cultural standards and their influence on shaping modern Chinese society.

Books have the power to galvanize. As repositories of memory, history, and ideology, they have inspired social revolutions and been banned by regimes threatened by their contents. Consequently, the censorship of books can serve as a barometer for oppressive social and political norms. As a child born on the cusp of the Cultural Revolution, Xiaoze Xie has experienced the profound power of books firsthand. Formative memories of his grandmother entertaining family and friends with epic tales mined from classic novels dovetail with recollections of his father, a school principal, who was forced to collect banned books slated for destruction under Mao. Those memories serve as a point of departure for creating the works included in this exhibition. Those doomed titles from the artist’s youth became forbidden, yet tantalizing objects that have continued to inspire Xie and have become a central aspect of his artistic practice.

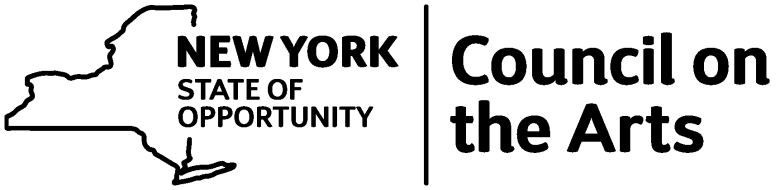

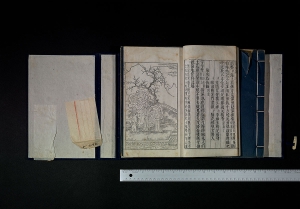

“Xiaoze Xie: Objects of Evidence” explores the subjectivity of censorship in relation to the shifting nature of sociopolitical and religious ideologies. Xie’s focus on books banned in China was initiated during a 2014 residency as a faculty fellow at the Stanford Center at Peking University (PKU) when the artist compiled an index of banned books from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), through the Republic of China (1911–49), and into the present day. Through paintings, installation, photography, and video, the artist expanded this research project to trace the history of banned books, including Dream of the Red Chamber (Hong Lou Meng) by Cao Xueqin and Water Margin (Shui Hu Zhuan) attributed to Shi Nai’an, which have become among the most revered and beloved novels in Chinese literature. Xie’s resulting body of work provides a means to chart changes in cultural standards and their influence on shaping the modern Chinese society.

Xiaoze Xie was born in 1966 in Guangdong Province, China. He received a BFA in Architecture from Tsinghua University in 1988, an MFA from the Central Academy of Arts and Design in Beijing in 1991, and an MFA from the University of North Texas in 1996. The artist currently lives and works in Palo Alto, California, where he serves as the Paul L. & Phyllis Wattis Professor of Art at Stanford University.

Michelle Yun

Senior Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art

Asia Society Museum

Michelle Yun, senior curator of modern and contemporary art and curator of "Objects of Evidence" at Asia Society Museum, interviewed Xiaoze Xie about his creative process and the concepts behind the paintings, photography, video, and installation featured in the exhibition. The following is a transcript of that conversation

MICHELLE YUN: Books and libraries have figured prominently in your work for over a quarter of a century. Would you please explain your relationship to books and how they became a primary subject within your artistic practice? How has this focus shifted over time?

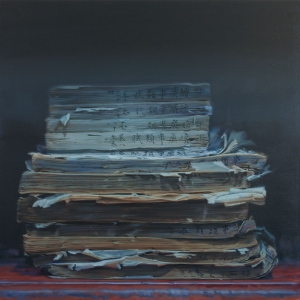

XIAOZE XIE: I became interested in books as a subject of my painting in 1993, shortly after I moved to the United States. I was fascinated by both the potential meanings and forms of the subject. For me, books are the material form of something abstract, such as thoughts, memory, and history. In the many years that followed, I continued to expand my subject to include Chinese thread-bound books, museum library collections, and eventually newspapers.

MY: Your most recent body of work, currently on view at Asia Society Museum, takes on as its subject the history of literary censorship in China. How did you become interested in this topic?

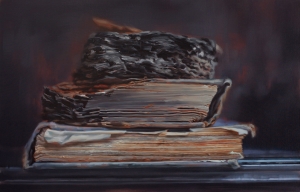

XX: As I continued to paint books in the 1990s, I was also interested in what people have done to books. I painted monumental volumes decorated with gold-leafed edges as well as neglected books in silent decay. I also made installations based on specific historic events such as the destruction of books by the Nazis during the Second World War and by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. All these led to the current project on the history of banned books in China. The books in my “Chinese Library” paintings are all closed and stacked; however, in the photographs in the banned books project, their pages open up for the first time. Content is brought to the fore for close examination.

MY: You grew up during the Cultural Revolution and have stated previously that a memory of your father, who was a school principal, collecting banned books slated for destruction left a great impression on you. Would you please share any recollections of growing up during the Cultural Revolution that have had an impact on your artistic practice regarding this project in particular?

XX: I grew up in the rural area of southern China during the Cultural Revolution so there was little culture one could access—serious “malnutrition,” I’d say. I have vague memories of big parades, propaganda paintings, and slogans. In my father’s office, I saw piles of old books which people were urged to turn in to designated places to be destroyed. I had a strong feeling that those books were mysterious and dangerous, but did not understand exactly what was going on. One doesn’t know what kind of seeds an experience could plant for the future.

MY: Through this body of work you utilize a broad range of media— painting, photography, video, and installation—to deconstruct the history of censorship in Mainland China. Would you please elaborate on your vision of how these visual art forms complement each other to explore this complex subject?

XX: The project started with reading and research and eventually involved searching, collecting, and photographing objects; consulting and interviewing various individuals (scholars, authors, editors, and officials in publishing houses); organization and display of materials, etc. The mediums I employed are necessary and direct ways to tell this complex story. The installation of books and life-size photographs provide concrete evidence of censorship, while the documentary film contextualizes the history of censorship and offers different perspectives on related issues.

MY: You have amassed a significant collection of banned books—over 750 titles to date—from the Qing dynasty to the present. Was it difficult to identify and source these books? How did you research for this project? Would you please explain the organizing rationale of your selection and display of the books as part of your Objects of Evidence installation?

XX: I used many books such as A Brief History of Banned Books in China (Chen Zhenghong and Tan Beifang), A Complete Introduction of Chinese Banned Books (An Pingqiu and Zhang Peiheng), and other materials as reference tools to compile a long list of titles to try to gather. There are many publications available on premodern banned books history. Unfortunately, it was much harder to find sources of information on banned books of the past few decades since the topic itself is sensitive. For modern books, I set out to locate and purchase the original editions (those published before they were banned) from the internet and used bookstores. For premodern titles, I searched the databases of public libraries; I identified many great entries in the rare book collections of Peking University in Beijing and Fudan University in Shanghai and negotiated with these institutions to access and photograph the books on site.

In the installation, the books are organized by time, genre, and author. Key authors are highlighted with multiple entries. Original editions are placed on the top layer. These are supplemented by later publications and reference materials on the lower level.

MY: How do you feel your work presents the history of censorship in China? Through your research, have you found underlying commonalities or connections among the types of materials being censored during the various periods represented in the exhibition? Have you come across banned books that have had their status change over time due to shifting social ideologies?

XX: Given the vast history of banned books in China, I feel what I have done is merely a drop in the ocean. However, I am as passionate about this ongoing project as ever. In working with these materials, I have found recurring themes and genres in different periods as well as changing patterns of control and tolerance. Erotic work has been banned over and over again yet has remained popular over time. Writing about history, which often resonates with current politics, has proved to be a highly risky territory. By looking at the banned titles from Chronology of Chongzhen Emperor Reign Period to Documents of Ming Dynasty (both from the Qing dynasty about late Ming dynasty history) to Anti-Rightist Whole Story (about the 1957 political campaign), a repetitive pattern of censorship on history writing clearly emerges.

As social conditions change, a previous ban could be lifted. Some of the titles featured in my photographs, such as The Peony Pavilion and Dream of the Red Chamber, were banned for being “obscene” multiple times in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Today, they are considered to be among the greatest works in the history of Chinese literature.

MY: You have developed a searchable database of banned books in China. Would you share the impetus behind its creation? Who would be your ideal user for this database?

XX: While developing this project, I’ve written exhibition proposals for huge installations in ideal, large spaces. I’ve come to realize that the number of objects and images that can be included is always limited by the scale of the available exhibition space; and it is almost impossible to present the variety and richness of the materials as well as the project’s breadth of time and ambition in a physical space. I also found myself caught in competing desires to protect the objects while creating interactive experiences for the audience. A searchable database is a good solution. It presents a more inclusive, if not comprehensive, view of the project. The database offers examples, facts, clues, and connections that allow viewers to further navigate the history of censored publications and draw their own conclusions.

MY: What would you like visitors to learn about the history of censorship in China and take away from a visit to your exhibition?

XX: Through these objects, images, and stories, I hope the audience will be able to get a sense of the vastness and continuity of a history of thought control, with all its complexity and texture. Banned books encapsulate political, religious, and moral conditions and reflect power relationships in different times. As the pursuit of freedom of expression often comes at a cost, I do hope that one remains hopeful despite the weight of this history.

To enjoy Asia Society's free audio guide for "Xiaoze Xie: Objects of Evidence" just look for the audio icon next to select artworks in the exhibition.

For easier mobile access, listen at Soundcloud.

Installation views of “Xiaoze Xie: Objects of Evidence." Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2019

Generous support for “Xiaoze Xie: Objects of Evidence” is provided by Bo Wu, The Lou Foundation, and the Fortinet Founder.

This exhibition was made possible with support from the Department of Art & Art History at Stanford University.

Asia Society appreciates the cooperation of Chambers Fine Art.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Global Council on Asian Arts and Culture, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and New York State Council on the Arts.