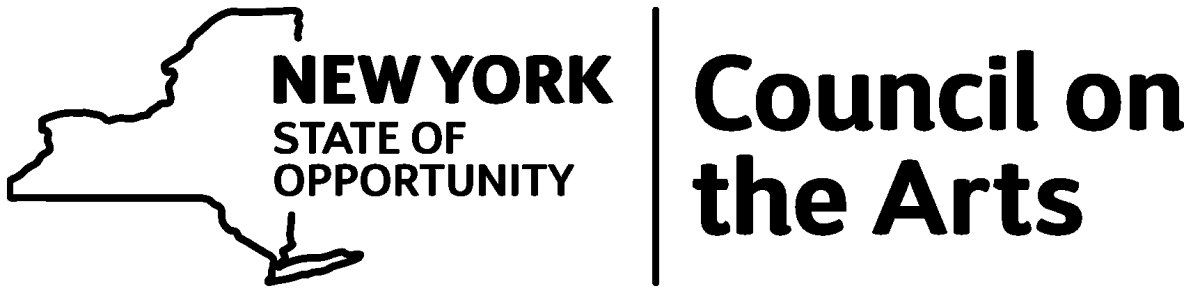

Reza Aramesh examines the power imbalance between captor and captive and the aestheticization of violence in media coverage of wartime atrocities. The exhibition focuses on Aramesh’s series of limewood sculptures inspired by seventeenth-century Spanish Christian iconography of martyred saints. His models, predominantly young, non-European male subjects, exude a homoerotic sensibility that adds a charged religious and sexual dynamic within representations of violence and evokes the military practice of sexual humiliation as a form of torture.

Reza Aramesh restages political conflicts in his sculptures, photographs, and performance works to reassess societal conventions that have come to define identity or ethnicity. This exhibition showcases the artist’s series of sculptures depicting young men in pain, sourced from war reportage images found online as well as in newspapers; their titles refer to specific historic political events and conflicts. The artist’s interest in seventeenth-century Spanish painted limewood sculptures of martyred saints inspired his choice of medium and influenced his exploration of the relationship between mythology and martyrdom. Aramesh’s choice to use limewood and his hyperrealistic style elevates the statues to the level of religious icons. His models, predominantly young, non-European male subjects, exude a homoerotic sensibility that adds a charged religious and sexual dynamic to the representation of violence and evokes the military practice of sexual humiliation as a form of torture.

The four sculptures on display are featured against what at first glance appears to be neo-Baroque decorative wallpaper. Upon closer inspection, it becomes apparent that the images of tortured figures, like those seen in contemporary news media, form the wallpaper’s motif. For his design, the artist selected a shade of green known as eau de Nil (water of the Nile), a color that dominated nineteenth-century upper-class interiors as part of the Egyptomania craze that swept colonial-era Europe. The charged sculptures of contemporary subjects against a backdrop that evokes a politically-fraught period of colonial conquest through military force mirrors contemporary society’s troubling penchant for violence to achieve socioeconomic and political gains.

Reza Aramesh was born in Iran in 1970 and currently lives and works in London. He has been the subject of numerous solo and group exhibitions. Reza Aramesh:12 noon, Monday 5 August 1963 is the artist’s first solo museum exhibition in the United States.

Michelle Yun

Senior Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art

Asia Society Museum

Michelle Yun, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and curator of this exhibition, interviewed Reza Aramesh about his creative process and the concepts behind the limewood sculptures featured in his exhibition Reza Aramesh: 12 noon, Monday 5 August 1963. The following is a transcript of that conversation.

Michelle Yun: Would you please share some background about how you began your artistic practice?

Reza Aramesh: Growing up in the south of Iran, we didn’t have access to museums, and there were no museums or art galleries in the city where I lived. However, there was an amazing secondhand bookshop near my school, which had lots of books containing pictures of European paintings and sculptures. They were all in English, which I couldn’t read, but I would buy them for their pictures. This is how I became interested in art.

MY: Much of your work is conceptually grounded by meticulous research often related to sociopolitical events. Would you please share the significance and criteria for the selected events and images that inspire your artworks?

RA: A lot of my artworks are attempts to navigate the history of war and, in particular, the history of the subjected body into mythology. I am using social and political conflicts of the present time and recent past as source materials in order to link to and create a dialogue with the artists of the past. This allows me to use images and events that perhaps I have not witnessed myself as source material by reappropriating found reportage images of conflict that I might not be subjected to directly . . .

This is following in the tradition of my artistic ancestors like Goya, José de Ribera, Andrea Mantegna, Caravaggio, and others. When I look at the work of these artists who depict suffering of saints and civil wars, I see images of Vietnam, the Middle East, and American soldiers . . . displacement, suffering, violence, and loss. I wanted to pick up source materials from different times—ranging from the Vietnam War until present—and different locations in order to pose the question: “Is suffering a universal human condition?” Also to link our present to the Homeric past.

My process of looking and creating an archive of contemporary war images, which come from news sources, is very linear. What I mean by that is, I first collect all the photojournalistic materials of a war or a conflict that I can get a hold of from websites or newspapers. For the second stage, when I am making a body of work for an exhibition, I go back to the archives and I start creating artworks that can respond to a particular image or an event.

MY: Would you please expand upon your process to create this series? What were some of the events that inspired the figures depicted in this exhibition?

RA: Throughout history, we have been telling stories of our wars, conflicts, and sufferings in the form of poetry, literature, and visual art. This is where I find common ground with the western canon. Particularly for this body of work exhibited at Asia Society Museum, I began to enter a dialogue with some of the seventeenth-century Spanish artists by creating four polychrome, hand-carved busts of unknown soldiers. I also made a direct reference to Andreas Schlüter’s dying warriors. The busts in the exhibition reference reportage images of conflicts from the 1960s until very recent events like the Vietnam War, the Iran-Iraq War, the Kurdish-Turkish conflict, and the Iraq-United States war.

MY: Does the viewer need to be aware of these historical events to appreciate the work?

RA: Not at all, the same way a reader might enjoy the poetry of Homer’s Iliad without having to know the sources. Likewise, the story of the Iliad is about humanity and not a particular location. The location where the war takes place is only a stage.

MY: What inspired you to create your series of limewood sculptures?

RA: In 2010 I saw an incredible exhibition of polychrome sculptures from seventeenth-century Spain, called The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700 curated by Xavier Bray at the National Gallery in London. It blew my mind. I kept going back to see the exhibition over and over again. This was the starting point for this series of work. I started looking at the idea and mythology of martyrdom using the material vocabulary of seventeenth-century Spanish artists.

MY: You designed the wall treatment specifically for this installation. Would you please elaborate on the symbolism of the color and patterning of the wallpaper and how you’d like the installation to be read as a whole?

RA: The wallpaper is designed in dialogue with a typical eighteenth-century French style. The base color is called eau de Nil (water of the Nile), which was considered a luxurious color that was often used in palaces and stately homes during the nineteenth century. I decided to take a common pattern of the period wallpaper and juxtapose it with some of the violent images of recent wars. This creates a background for the four sculptures which, in turn, makes the whole piece read as a single installation rather than individual sculptures. Upon entering the gallery, the viewer will become the subject rather than just a spectator.

MY: Do you think that your work takes on alternate meanings or significance depending on the context in which it is viewed?

RA: Definitely.

To enjoy Asia Society's free audio guide for Reza Aramesh: 12 noon, Monday 5 August 1963, just look for the audio icon in the exhibition.

For easier mobile access, listen at Soundcloud.

Generous support for Reza Aramesh: 12 noon, Monday 5 August 1963 is provided by Sonny and Gita Mehta.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Global Council on Asian Arts and Culture, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York State Council on the Arts, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.