This exhibition features a selection of the finest artworks from the renowned Asia Society Museum Collection. Included are Chinese, Korean, and Japanese ceramics; Indian and Cambodian Hindu sculptures; and sculptures from South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Himalayas that show imagery associated with the transmission of Buddhism across the region.

Even before John D. Rockefeller 3rd (1906–78) established Asia Society in 1956, he was deeply involved with the arts and culture of Asia. He firmly believed that art was an indispensable tool for understanding societies, and thus made culture central to the new multidisciplinary organization that would encompass all aspects and all parts of East, South, and Southeast Asia and the Himalayas. From 1963 to 1978, he and his wife, Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller (1909–92), worked with art historian Sherman E. Lee (1918–2008) as an advisor to build the Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, which was later bequeathed to Asia Society. The group of spectacular historical objects they assembled—including sculpture, painting, and decorative arts—became the core of the Asia Society Museum Collection and is now world renowned. The Collection is distinguished by the high proportion of acclaimed masterpieces, representing the artistic pinnacles of the cultures that produced them, to which additional high-quality gifts and acquisitions have been added since the original bequest to Asia Society.

The selections on view showcase the breadth and depth of creative expression across Asia created by artists and artisans with extraordinary skill. To this day, the objects remain an important means for sharing the talent, imagination, and deep history of the peoples of Asia with audiences all over the world. In these galleries, we invite viewers to explore the specialized artistry of Asian ceramics, metalwork, and stone carving, and the development of Hinduism and Buddhism in Asia through some of the most re ned and accomplished examples of the region’s great artistic traditions.

Among the most extraordinary historical examples of Asian craftsmanship are vessels created for holding food and drink. The appreciation of wines, teas, and cuisine have long traditions in China, Korea, and Japan, and craftsmen developed a myriad of vessel forms and decorative patterns to enhance the visual appeal of food and drink in domestic, imperial, and ritual settings. The unique forms—from elaborate bronze Chinese vessels to simple ceramics for the Japanese tea ceremony—and the materials they are made from often offer clues to their functions.

Dishes, bowls, platters, cups, jars, and bottles comprise some of the most common objects for daily use in East Asia. Many of these wares have survived—and maintain much of their original beauty—even after hundreds of years in large part due to the development of strong, high- fired wares with equally tough glazes. In addition to domestic objects, the masterpieces on view in this section include pieces created for royals and elites and for export. Most of the vessels originally came from larger sets made for drinking tea or wine, for tea ceremonies, and for imperial feasts and banquets.

This jar, though more decorative than functional, is based on the form of vessel used for storing tea leaves. One of only a handful of seventeenth-century potters whose name is recognized today, Nonomura Ninsei operated an extremely successful kiln in Kyoto called Omuro that catered primarily to important patrons in Edo (present-day Tokyo). His seal is imprinted on the unglazed base of this important jar, which is decorated with mynah birds. It was designated an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government and Mr. Rockefeller had to obtain special permission to purchase it.

These very handsome sets may have been made as part of a larger set of dining ware and used as containers for delicacies during dinners or banquets at the royal court. The color and quality of the glaze on these elegant pieces has been esteemed not only in Korea but throughout East Asia for centuries.

This large, impressive flask is decorated with a three-clawed dragon, a symbol of imperial power, among lotuses and tendrils. It was possibly used at the Ming court in the early fifteenth century as a gift from the emperor to one of his attendants or to a foreign ruler or dignitary. Though the form of the flask has been traditionally used for holding liquids, the scale of this one indicates its function was probably decorative rather than functional.

Hinduism and Buddhism both originated in India and spread through the sacred languages of Sanskrit and Pali. Traders, missionaries, and scholars from India and Sri Lanka introduced these belief systems and their imagery to kingdoms of Southeast Asia, creating ties that began as early as the first century CE. These include the countries that we know today as Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar (Burma), and Cambodia.

Blended with indigenous beliefs, aspects of Indian Hinduism and Buddhism were incorporated in the art and architecture of Southeast Asia. Even in kingdoms where one of these belief systems came to dominate, deities from the other religion also found an important place. Often the same artist made sculptures for both religions. Geographic and political ties among Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms led to further cultural and artistic exchange, the effects of which can be seen on some of the masterpieces on view in this section.

Rulers and wealthy patrons supported the production of impressive icons from expensive and highly refined materials and the creation of Hindu and Buddhist temples to house them. Moreover, the Hindu and Buddhist rulers of Southeast Asia frequently asserted their power by constructing a capital city with a temple at the center, providing a state setting for the representation of deities. These acts were demonstrations of their power in this life, but just as important—and perhaps more so—patrons carried them out with the expectation that they would be rewarded in the afterlife.

This figure and a male figure also on display in this exhibition have often been identified as a royal couple. The Cambodian custom of considering gods as tutelary deities that protect the kingdom through royal intermediaries, however, often makes it difficult to distinguish rulers from the divine. Angkor-period rulers commissioned the construction of huge temple mountains in mainland Southeast Asia. They filled them with religious scenes in relief and three-dimensional sculpture. These figures, both with oval-shaped faces, are in the style associated with a temple located at the center of the famed walled city of Angkor Thom. It was commissioned by the late-twelfth- to early-thirteenth-century ruler Jayavarman VII. This temple, the Bayon, was dedicated either to the Hindu god Brahma or the Buddhist deity Avalokiteshvara.

During the Chola period, adoration of the physical beauty of the divine was an integral part of bhakti, the Hindu tradition of devotion that emphasizes intense and intimate devotion to a personal god. This sculptural visualization of Shiva’s consort Uma represents the outward grace and sensuality that were considered manifestations of inner spiritual beauty. This image of Uma stands in the tribhanga, or triple-bend posture that emphasizes the sensual contours of Uma’s slim waist and full breasts and hips. Her gracefully raised hand once held a lotus or blue lily blossom, which is now missing.

By the seventh century, Buddhism was a major religious force across South, East, and Southeast Asia, after it spread dramatically following the death of its founder, Shakyamuni (“Sage of the Shakyas”) or the historical Buddha, who is traditionally believed to have been born in 563 BCE. The form of Buddhism known as Theravada, which emphasizes a monastic path to enlightenment, was adopted in Sri Lanka and subsequently became the predominant form of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Mahayana Buddhist doctrine, which argues that a wider group of followers—including members of the laity—can become enlightened, spread to East Asia and also had some presence in both South and Southeast Asia. Another movement was Vajrayana (Esoteric) Buddhism, which stresses attaining union with cosmic aspects of Buddhahood through ritual and meditation.

The pantheon of deities described in the religious texts and images associated with each of the three major strains of Buddhism show some distinctions. For example, Theravada Buddhist painting and sculpture are dominated by images that relate to the life and past lives of Shakyamuni. This subject matter also can be found in Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, but works associated with these branches frequently feature other fabulous beings like bodhisattvas, intermediaries who are able to escape the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara), but choose to remain active in the world to help others along the path to enlightenment. Images of bodhisattvas most often show these beings sumptuously adorned. They wear crowns or other headdresses, armbands, and necklaces and often feature the tall, matted coiffure of an ascetic. The Vajrayana Buddhist pantheon is the most diverse of all and includes, for example, depictions of a range of wrathful deities that play protective roles and help steer practitioners on the path to enlightenment.

Fantastic beings from all three forms of Buddhism are on view in this section, exemplifying the complexity of representation of Buddhist deities among these three Buddhist traditions across Asia.

This stone image of the “Sky-Gliding” (Khasarpana) form of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, Avalokiteshvara, once decorated an architectural niche. Avalokiteshvara demonstrates his compassion for all living beings by holding his right hand in the gift-bestowal gesture (varada mudra) above the “hungry ghost” (Suchimukha) who kneels beneath his right hand. He feeds this hungry ghost with drops of nectar that flow from his fingers. Represented on the base are Suchimukha to the left and the terrifying protective deity Hayagriva to the right.

This sculpture presents the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in the form of “All-seeing Lord of the Infallible Noose” (Amoghapasha Lokeshvara) and is identified by the rope held in his bottom hand. Once ensnared in this sacred noose, the devotee must tell the truth about and to himself, an act that can sever the bonds of illusion and help a practitioner achieve enlightenment. Amoghapasha Lokeshvara is one of the guardian deities of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal and is also worshiped for day-to-day well-being.

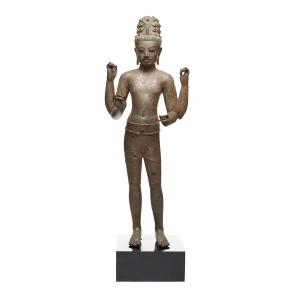

This large, cast image of the Bodhisattva Maitreya (the Buddha of the Future, destined to become the next mortal buddha after Shakyamuni) is one of the finest eighth-century Southeast Asian bronze sculptures in the world. The scanty clothing, long matted hair, and lack of jewelry indicate that this image represents Maitreya as an ascetic bodhisattva, a type found throughout Southeast Asia from the seventh through ninth century. Bodhisattvas appealed to practitioners and were worshipped along with the Buddha all over South and Southeast Asia.

To enjoy Asia Society's free audio guide for Masterpieces from the Asia Society Museum Collection, just look for the audio icon next to select artworks in the exhibition.

For easier mobile access, listen at Soundcloud.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Global Council on Asian Arts and Culture, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York State Council on the Arts, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.