Clouds Stretching For A Thousand Miles: Ink in Asian Art features selected recent acquisitions from the Asia Society Museum Collection and celebrates the versatility and enduring influence of the calligraphic ink tradition across Asia. Exemplary works by Gu Wenda, Huang Yan, Minjung Kim, Qiu Zhijie, and Sun Xun, displayed alongside two illuminated Qur'ans from China and Central Asia, reveal the innovative use of ink and calligraphy in visual expression, from the fourteenth century to the present, across Asia and the diaspora.

The title of the exhibition comes from the celebrated Tang Dynasty calligrapher and scholar Chang Yen-Yuan (c. 815–c. 875 CE), who likened the primary stroke of traditional calligraphic practice — the horizontal line — to "clouds stretching a thousand miles." This metaphor aptly describes the way contemporary Asian artists have embraced traditional calligraphic painting traditions and underscores the enduring importance of text and language across East Asian, West Asian, and Islamic art canons.

This presentation introduces ink works that are part of Asia Society's new collecting focus and continues the Museum's initiative to connect objects from the Traditional Collection to works from the Contemporary Collection through medium, techniques, and ideas that artists actively draw upon in the twenty-first century. Clouds Stretching for a Thousand Miles highlights the distinct art developments from the region and the creative, and sometimes subversive, methods that contemporary Asian artists have adopted to mine their respective cultures for inspiration.

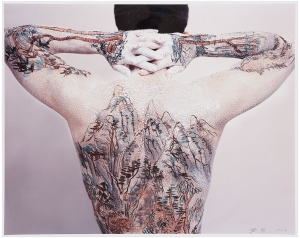

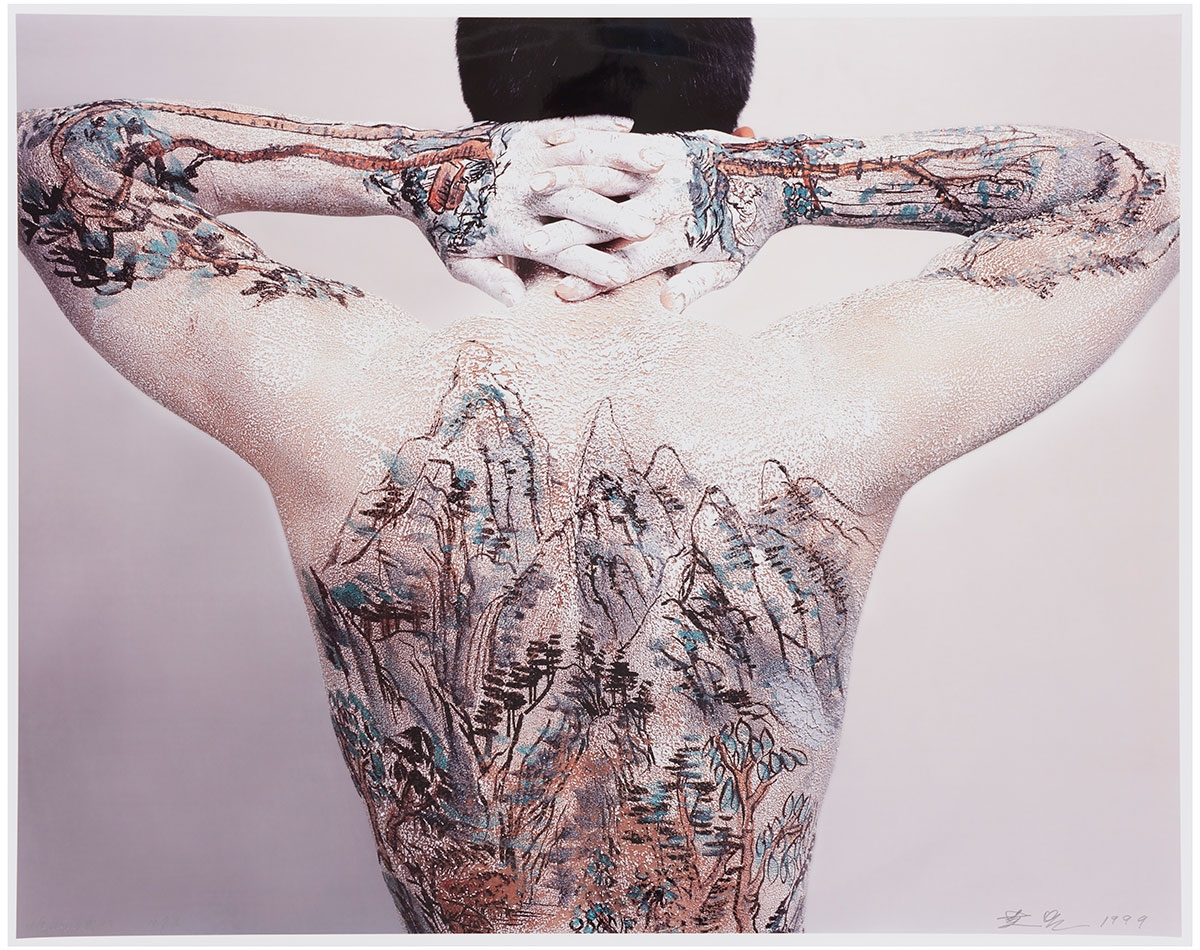

Huang Yan (born 1966 in Jilin, China; lives and works in Changchun). Chinese Landscape—Tattoo, 1999. Chromogenic print. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Ethan Cohen in honor of Professor Jerome A. Cohen and Joan Lebold Cohen, 2016.1.1-13

Huang Yan's reinterpretation of traditional Chinese landscape painting challenges conventional artistic practices and creates a unique dialogue between the body and nature, and the past and present. In 1999 he began creating photographs that documented traditional landscape compositions, in the Song-dynasty style, painted onto the human body. Chinese Shan-Shui (Landscape) – Tattoo, 1999, is an early series of thirteen photographs that depicts a mountain landscape painted on a nude male torso in various poses. The title variously pays homage to the tradition of Chinese landscape painting while also alluding to society's increasing fixation with body art. By using the body as his canvas the artist attempts to reunite man and nature, which he believes have become estranged from one another in contemporary society.

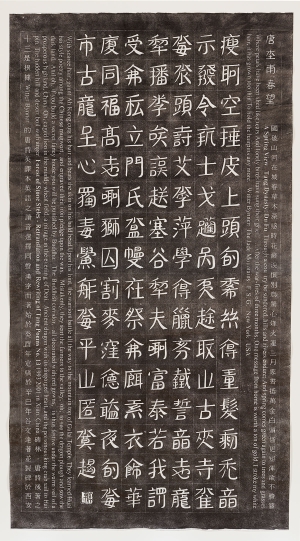

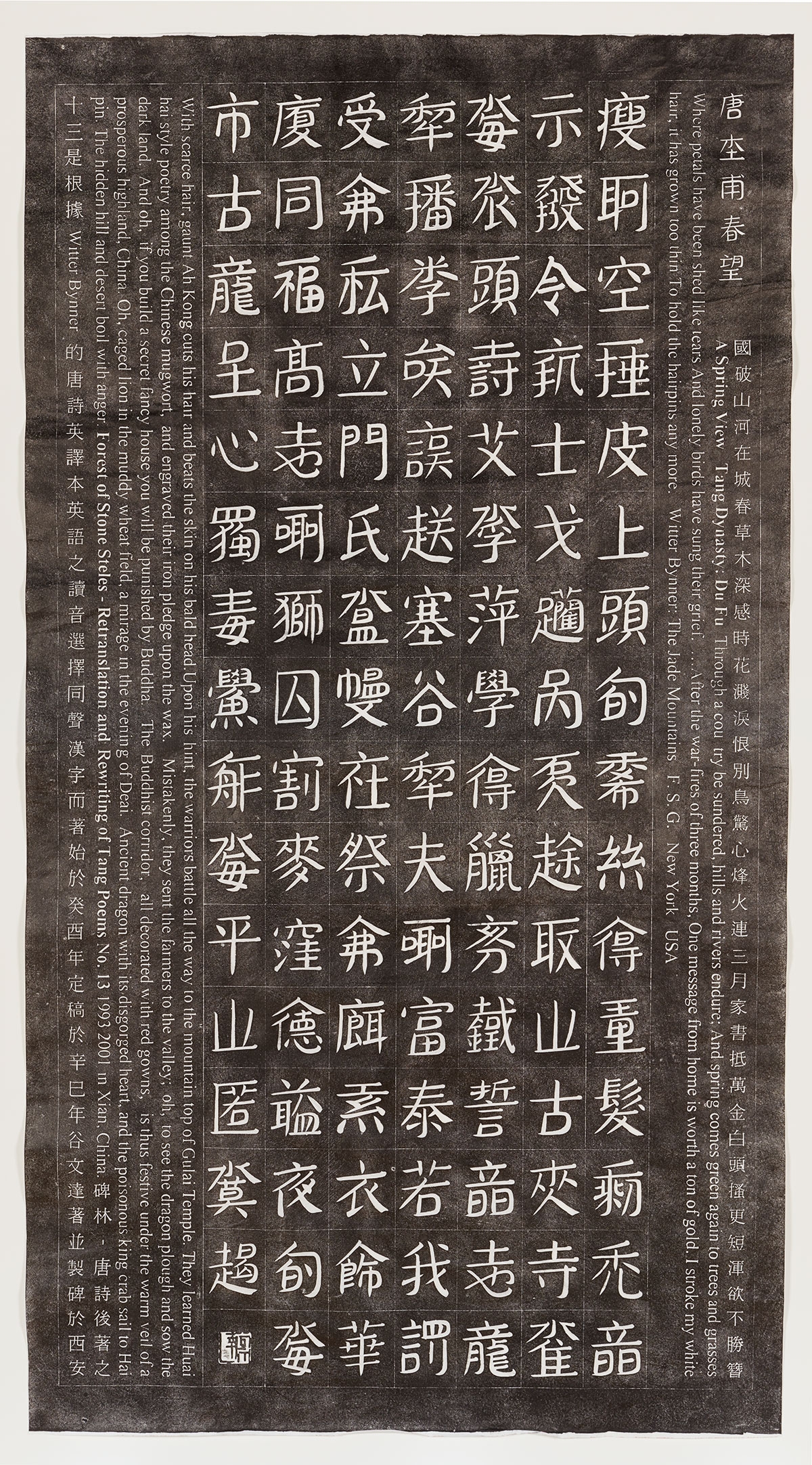

Gu Wenda (born 1955 in Shanghai, China; lives and works in New York). Forest of Stone Steles #13, 1998. Ink rubbing on rice paper. Asia Society, New York: Asia Society Museum Collection, 1998.2

Gu Wenda uses language as a medium to deconstruct meaning, challenge traditions, and examine the outcomes of cross-cultural exchanges. Forest of Stone Steles #13, and Forest of Stone Steles #33, both from 1998, exemplify Gu's play on the traditional art practice of creating ink rubbings. This series references the Stele Forest, a museum in the city of Xi'an that includes more than one thousand stone stele records of important political and cultural moments in Chinese history. These rubbings are from a series of steles created by the artist between 1993 and 2005 that record the translation of Tang dynasty poems into English by the American poet Witter Byner and published in his 1929 anthology "The Jade Mountain." Gu proceeds to phonetically translate the poem back into Chinese and re-interpret his translation back into English including the misinterpretations that naturally occur between these versions. His use of translation in this context highlights the fluidity of meaning and the subjectivity of interpretation over time and between cultures.

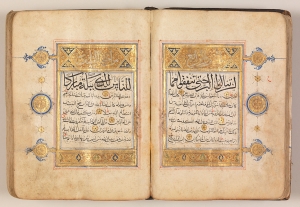

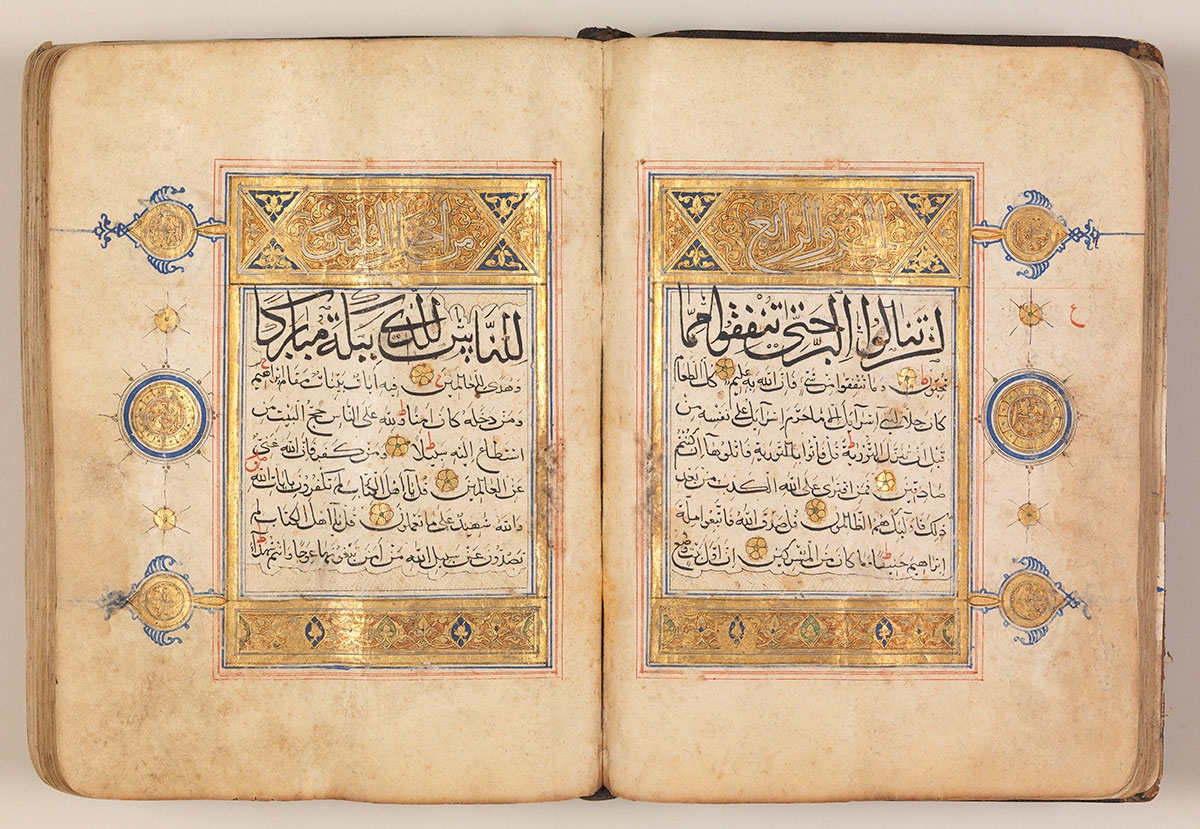

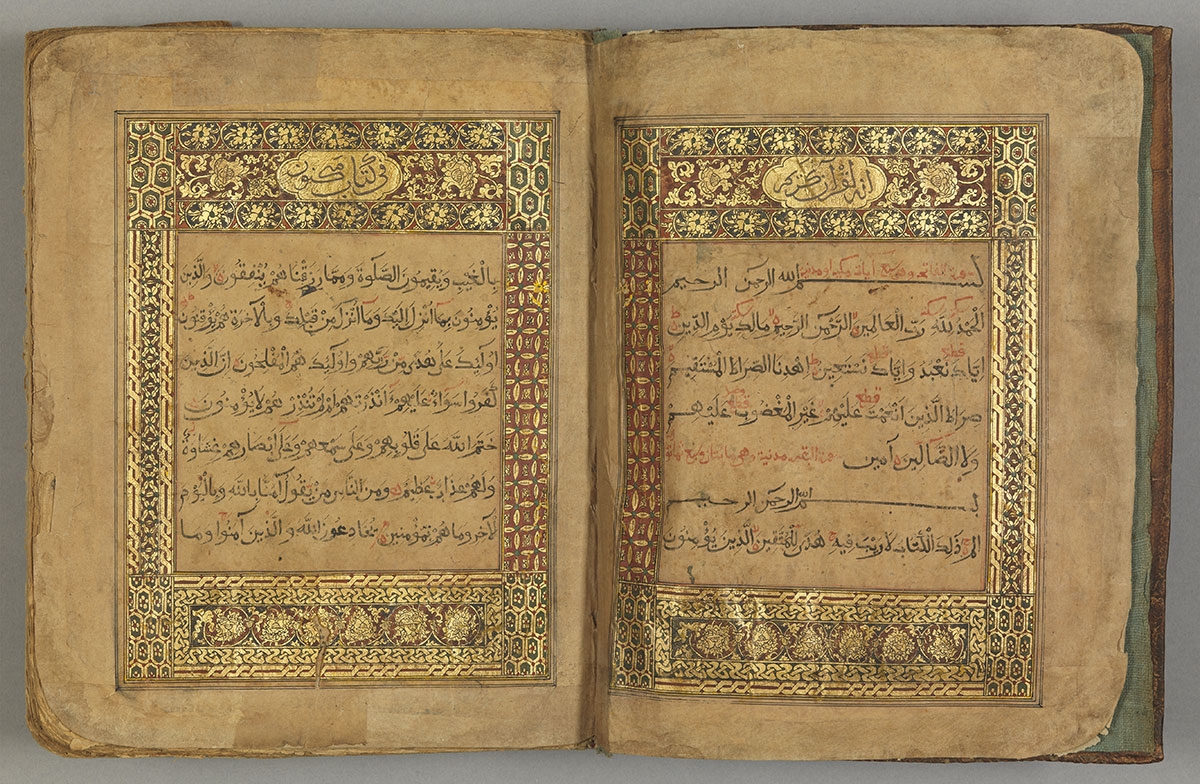

Qur'an. Ca. 1300. Central Asia. Ink, color, and gold on paper; Morocco leather binding. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Acquisitions Fund, 2018.7

This rare Qur'an, the sacred scripture of Islam, survives from Central Asia, most likely the area of current day Uzbekistan. Writing transmits the word of God and therefore the art of writing is the most highly regarded of all the arts in the Islamic world. The sacred classical Arabic text was transmitted from the Iranian world across Central Asia to China. This Qur'an consists of fifteen lines of black muhaqqaqq calligraphy per page. The elaborate decoration includes gold and polychrome rosettes, illuminated roundels with blue ornamental outline in gold kufic calligraphy, and illuminated roundels with radiating finials, as well as illuminated panels.

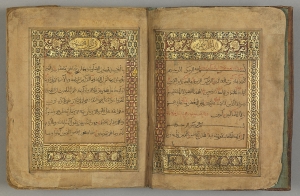

Qur'an. Ca. late 17th century. Western China. Ink, color, and gold on paper. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Acquisitions Fund, 2018.8

The transmission of Islam to China was already underway in the eighth century; the impact that Chinese culture had on the production of the Islamic sacred text is clear in this illuminated Qur'an from around nine centuries later. Decorative motifs common to China, like the peony and geometric patterns, have been incorporated into the illumination. The calligraphy itself is in the style of script known as sini that developed in China. This style derived out of the form of calligraphy transmitted across Central Asia to China.