On the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of Asia Society, this exhibition celebrates the legacy of collecting and exhibiting Asian art that John D. Rockefeller 3rd (1906–1978) and Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller (1909–1992) set in motion for Asia Society. Even when taken out of their original cultural contexts these artworks can serve as a conduit for sharing the talent, skill, imagination, and deep history of the peoples of Asia. In this exhibition, historical and contemporary works are juxtaposed to trigger more informed and distinctive ways of thinking about the artworks, their creators, and how they are displayed.

Before John D. Rockefeller 3rd established Asia Society in 1956, he had been deeply involved with the arts and culture of Asia. Rockefeller firmly believed that art was an indispensable tool for understanding societies, especially in Asia, and thus made culture central to the new multidisciplinary organization that would encompass all aspects and all parts of Asia. From 1963 to 1978, the Rockefellers worked with art historian Sherman E. Lee (1918–2008) as an advisor to build their collection. Together they assembled a group of spectacular historical works—including sculpture, painting, and decorative arts from East, Southeast, and South Asia, and the Himalayas—that became the core of the Asia Society collection of traditional art. This collection is distinguished by the high proportion of acclaimed masterpieces, to which additional high quality gifts and acquisitions have been added since the original bequest to Asia Society.

As a complement to these holdings, Asia Society inaugurated a collection of contemporary Asian and Asian American art in 2007. While the traditional collection began with a desire to create a better understanding among cultures, the impetus for the Museum’s collection of innovative new media art was to broaden the understanding of Asia’s artistic production through works that demonstrate a savvy, and nuanced understanding of advances in new technologies, many of which were first developed in Asia. Using video, photography, and other new media, contemporary artists from Asia and the diaspora have been able to respond to the shifting sociopolitical, economic, and cultural changes that are occurring across the region. The joining together of these facets of Asia Society’s inimitable collection showcases the breadth and depth of creative expression across Asia. Moreover it reflects the rich and diverse cultural history of the region and highlights how elements of the past continue to be present in much of today’s art.

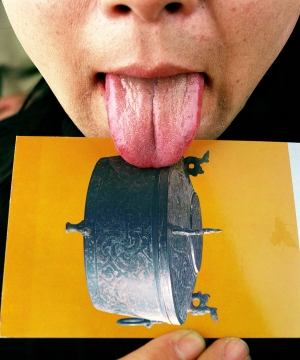

Beginning August 10, visitors will have the pleasure of seeing a remarkable pair of seventeenth-century Japanese screens featuring pheasants under cherry and willow trees, and irises and mist attributed to Kano Ryokei; a masterfully cast Indian Chola-period bronze of Krishna dancing on Kaliya; a recently acquired seventeenth-century Indian painting of Krishna and Balarama in pursuit of the demon Shankashura; and a new section of Hon’ami Koetsu’s 1626 poem scroll with selections from the Anthology of Chinese and Japanese Poems for Recitation (Wakan Roei Shu). The rotation will also feature a new selection of photographs from Cang Xin’s Communication Series.

Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator of Traditional Asian Art

Michelle Yun, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

As museum visitors in the United States, we have become accustomed to viewing objects created for temples, personal devotion, or specific decorative purposes as works of art that can be appreciated outside of their original contexts. Yet looking at objects in completely alien contexts may entirely transform the viewers’ understanding or interpretation. For Village and Elsewhere: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, Jeff Koons’ Untitled, and Thai Villagers, 2011, the artist Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook (born 1957) invited a group of children from the Thai countryside to a local Buddhist temple for a lecture by one of the residing monks about the two western paintings noted in the title. In this unusual context the works take on entirely different meanings as the monk uses the reproductions as visual aids for a lesson on Buddhist teachings. The ensuing dialogue reveals a myriad of cultural nuances and assumptions between East and West, and among social classes. It opens up the possibility for alternative modes of art appreciation outside a conventional western museological structure. The ideas explored in this work embody the premise of this exhibition and illustrate how mindful we must be of the impact of museum display, while also recognizing that opportunities for meaningful dialogues can be initiated when looking at artworks placed outside of their original contexts.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook (b. 1957 in Trad, Thailand; lives and works in Chiang Mai). Village and Elsewhere: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, Jeff Koons’ Untitled, and Thai Villagers, 2011. Single-channel video with sound. Duration: 19 minutes, 40 seconds. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz, 2015.7. Image courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook is one of the leading video artists from Thailand. She began her practice as a sculptor and printmaker, but shifted her focus toward video beginning in 1998. The artist was first introduced to American audiences through the landmark Asia Society exhibition “Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions” in 1996. Rasdjarmrearnsook’s subject matter is based on dichotomies, such as the relationship between life and death, and the search for autonomy within cultural constraints. More recently her practice has encompassed notions of identity and difference through the lens of class hierarchies and regional idiosyncrasies. This video is from her “Village and Elsewhere” series, comprising photographs and videos created in 2011. This group of works is meant to highlight how artworks can take on many different meanings and lives, some of them not even envisioned by their creator. Rasdjarmrearnsook’s humorous and revealing documentation of a Buddhist teacher’s “art history lesson,” in which he uses reproductions of two iconic western paintings to demonstrate the relevance of the Five Precepts of Dharma, exemplifies the subjective understanding of an artwork depending on the context in which it is presented.

Head of Buddha. Thailand. Mon style, about 8th century. Limestone. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.76. Photography by Synthescape

Texts that describe how a Buddha’s face should look often use comparisons to natural forms. According to some texts, a Buddha’s face is supposed to have eyes like lotus petals, eyebrows like an archer’s bow, a nose like a parrot’s beak, and a chin like a mango stone. Although the ultimate inspiration for Thai Buddha images originated in India, the features of this head, with its high cheekbones, full lips, and broad nose, reflect the ideals of the Mon people, who lived in central Thailand from roughly the sixth to the eleventh century.

Flowers, plants, trees, and landscape in general have been sources of inspiration for artists for thousands of years. Artists everywhere have always studied and produced images of these captivating subjects. In East Asia the natural world has rich and complex symbolic associations originating in religious traditions, philosophical thought, and vernacular stories that have inspired artists’ work with these themes. The symbolism of some of the subjects found in nature have specific ethical and philosophical connotations. For example, the image of an evergreen pine tree is often associated with long life and stoicism through adverse conditions.

Artists from China and Japan often use imagery that relates to Confucian and Daoist philosophies. Bamboo, for example is emblematic of an upright Confucian character that will persevere through adversity; it may bend but will not break. There is a long tradition of retreating from the world among the Chinese literati, or educated elite, during times of social and political turmoil. For example the fourth-century scholar Xie An retired to East Mountain in Zhejiang province to avoid the politics of the Eastern Jin capital and study the Dao. Consequently a painting of or reference to a particular mountain or idyllic mountain setting may connote the notion of withdrawal in search of a more natural order during periods of corruption.

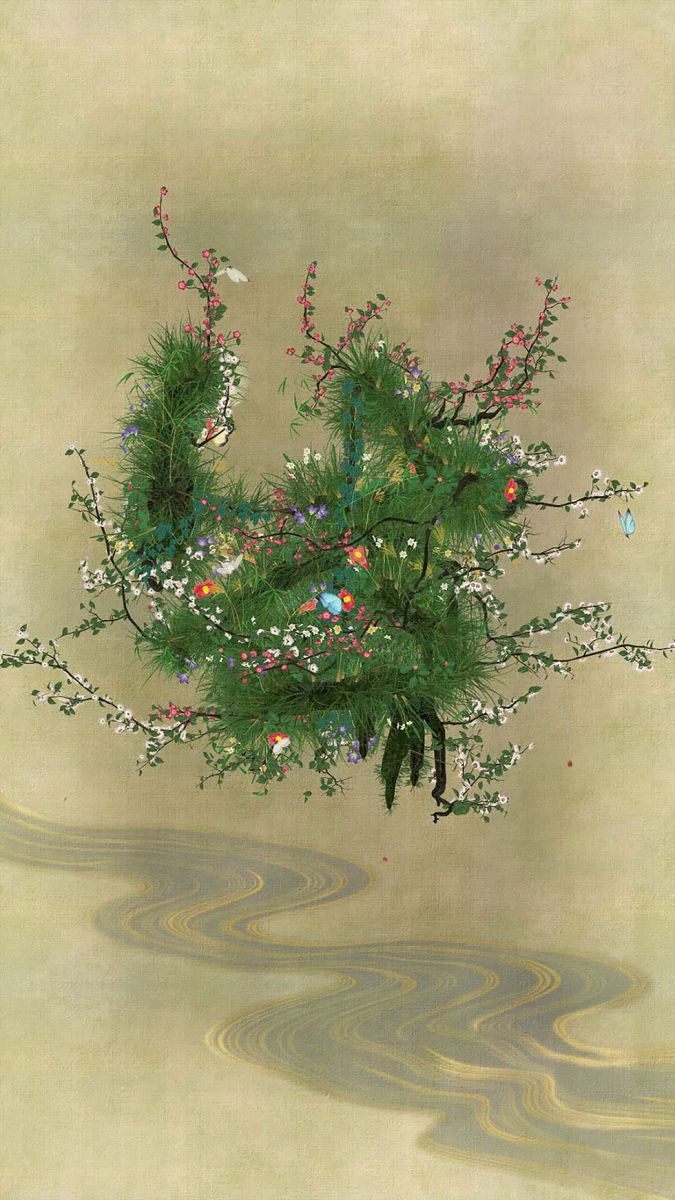

In East Asia, imagery from nature also often alludes to famous scenes from popular works of literature or poems. One theme in the literature and philosophy of East Asia that frequently appears in painting is that of flowers of the four seasons, which has roots in early Chinese poetry and has continued to inspire poets and other artists to this day. In Japan, where interest in the theme dates back to the eighth century, artists have excelled at depicting the seasons individually or transitioning from spring through winter in one painting or one pair of screens. This theme has continued to inspire contemporary artists who have used new technologies to explore this subject. The time-based medium of video can depict the passage of time by seamlessly animating the growth and decay of living things through the four seasons.

Jar. China, Jiangxi Province; Ming period, late 14th century. Porcelain with underglaze copper red (Jingdezhen ware). H. 20 x Diam. 16 3/4 in. (50.8 x 42.5 cm). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.153. Photography by Lynton Gardiner, Asia Society

This large jar is an outstanding example of fourteenth-century porcelain painted with underglaze copper-red pigment. The red color is notoriously difficult to achieve during firing, and pieces decorated exclusively with this color are scarcer than the well-known blue-and-white types. The central section of the jar is painted with a traditional Chinese theme called the Three Friends of Winter (suihan sanyou); plum, bamboo, and pine, symbolizing longevity, perseverance, and integrity, respectively.

teamLab(collective formed in 2001 in Tokyo, Japan). (Video still) Life Survives by the Power of Life, 2011. Single-channel digital work; Calligraphy by Sisyu. Duration: 6 minutes, 23 seconds. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Mitch and Joleen Julis in honor of Melissa Chiu, 2015.14. Video still courtesy the artist © teamLab, courtesy Pace Gallery

Life Survives by the Power of Life is a rumination on the nature of language, and more specifically the relationship between the western alphabet and kanji, Japan’s modern writing system based on Chinese pictographic script, and between the past and present. The video animation depicts the character “life,” written in kanji by the contemporary calligrapher Sisyu, through the lens of Japanese traditional painting, albeit brought to life as a moving image using new technologies developed in the twenty-first century. The specific reference to the four seasons alludes to a longstanding tradition in Japanese painting and provides an interesting juxtaposition to the pair of seventeenth-century screens depicting this subject also on view in the gallery. This work was created in the midst of the 2011 tsunami and subsequent Fukushima nuclear disaster that occurred in Japan. It serves as both a sign of our inherent vulnerability, as well as a testament to the collective resiliency of the human race in the face of great adversity.

Mami Kosemura (born 1975, Japan). (Video still) Flowering Plants of the Four Seasons, 2004–06. Three-channel animation with sound. Duration: 36 minutes, 30 seconds. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold and Ruth Newman, 2011.15

Inspired by traditional Japanese screen painting, Mami Kosemura created this “moving painting” installation in her studio by arranging seasonal plants and flowers into a composition emulating classical depictions of The Four Seasons. The artist recorded their growth and decay with a stationary digital camera over the course of a year and the resulting photographs were then collaged together to create a moving image. Kosemura has created a number of video works in which she examines various methods and styles of artistic production in the history of art across the world. Flowering Plants of the Four Seasons is the first of this ongoing investigation by the artist and is focused on the convention of Japanese traditional painting. Kosemura juxtaposes the process of copying directly from nature with the tradition of copying past master paintings to reflect the passage of time, as well as the cycle of death and renewal in nature and art.

Attributed to Kanō Ryokei (Japanese, died 1645). Pheasants under Cherry and Willow Trees and Irises and Mist. Japan, Kyoto Prefecture, Nishihonganji. Edo period (1615–1868), first half of 17th century. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink and color on gold leaf on paper. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.217.1-2. Photography by Lynton Gardiner, Asia Society

These screens are believed to have once been two of four sliding-door panels (fusuma) illustrating the transition from the cherry blossoms, willow, and pheasants of spring to the irises of summer. Nishihonganji, a prominent temple in Kyoto, still has a panel from the original set. The third panel is in the collection of the Honolulu Academy of Arts. The use of gold foil as background on screens dates to as early as the fourteenth century in Japan. The flowers, tree trunks, and pheasant are painted with bold forms as well as attention to detail, both characteristics of traditional Kanō-school style. The Kanō school was a prominent family of painters employed by Japanese feudal military rulers between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.

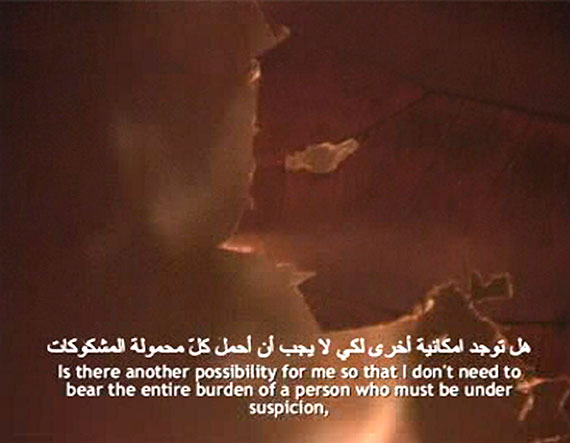

Fantastic legends featuring arduous journeys, battles, or tasks surround the plethora of deities that populate the Indian religious traditions. These tales spread with Hinduism from India to Southeast Asia, where they were adopted by local inhabitants and adapted to their native traditions. This epic narrative genre has continued to permeate artistic traditions up to the present, for example in images of stories from the Ramayana (Deed of Rama) and Arahmaiani’s video work I Don’t Want to Be a Part of Your Legend. Contemporary artists like Arahamaiani use the time-honored stories as metaphorical vehicles to illuminate and critique contemporary social and political issues.

The protagonists of these stories are superhuman men who can metamorphose in size, form, and character, or devoted women whose virtue is tragically questioned. Like the gods of Greek mythology, the characters from these tales engage in love and war among themselves, and intervene in human affairs. The sources for these stories range from ancient religious hymns and ritual texts, to philosophical treatises and great epics.

South and Southeast Asian sculptures and paintings of gods and other deities often include imagery that directly or indirectly alludes to tales from ancient epics. These stories would be familiar to worshippers through reading texts or viewing narrative drama and dance. This section of the exhibition focuses on tales related to the god Vishnu in his manifestations as Rama and Krishna.

Rama. Chola period, 11th century. Copper alloy. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.23. Photography by Synthescape

Sculptures of Vishnu’s avatara Rama were commissioned for Vaishnava temples to form an assemblage that included his wife Sita, his brother Lakshmana, and the monkey-general Hanuman. Rama, shown in the tribhanga, or triple-bend posture, is ornamented with jewels, a halo-wheel, and a high crown that would have made him the tallest figure of this group. A bow was once held in his raised left hand and an arrow, or arrows, in his right. These attributes are associated with the imperial hunt and reflect the heroism of Rama, the protagonist of the popular Indian epic the Ramayana.

Arahmaiani (b. 1961 in Bandung, Indonesia; lives and works in Yogyakarta). (Video still) I Don’t Want to Be a Part of Your Legend, 2004. Single-channel video with sound. Duration: 11 minutes, 34 seconds. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Dipti Mathur, 2015.2. Courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art © Arahmaiani

Arahmaiani is considered a pioneer in the field of contemporary performance art in Southeast Asia and is best known for her provocative videos, installations, sculptures, and performances that address social and political issues in her native Indonesia in an effort to challenge conservative attitudes toward religion, gender, and class. The artist was first introduced to American audiences in 1996 through the landmark exhibition “Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions” at Asia Society. This video references the Sanskrit epic of Ramayana. Sita, Rama’s wife, is put through a trial by fire to prove her purity and her survival serves as a metaphor for the resiliency and self-sustaining nature of the feminine in the face of oppressive male patriarchy. The accompanying lyrics, written and sung by the artist, underscore the lament of existence under these conditions. This particular video utilizes the traditional shadowplay format of wayang kulit to enact Hindu, folk, and Islamic mythology as a metaphor for contemporary political issues in Indonesia.

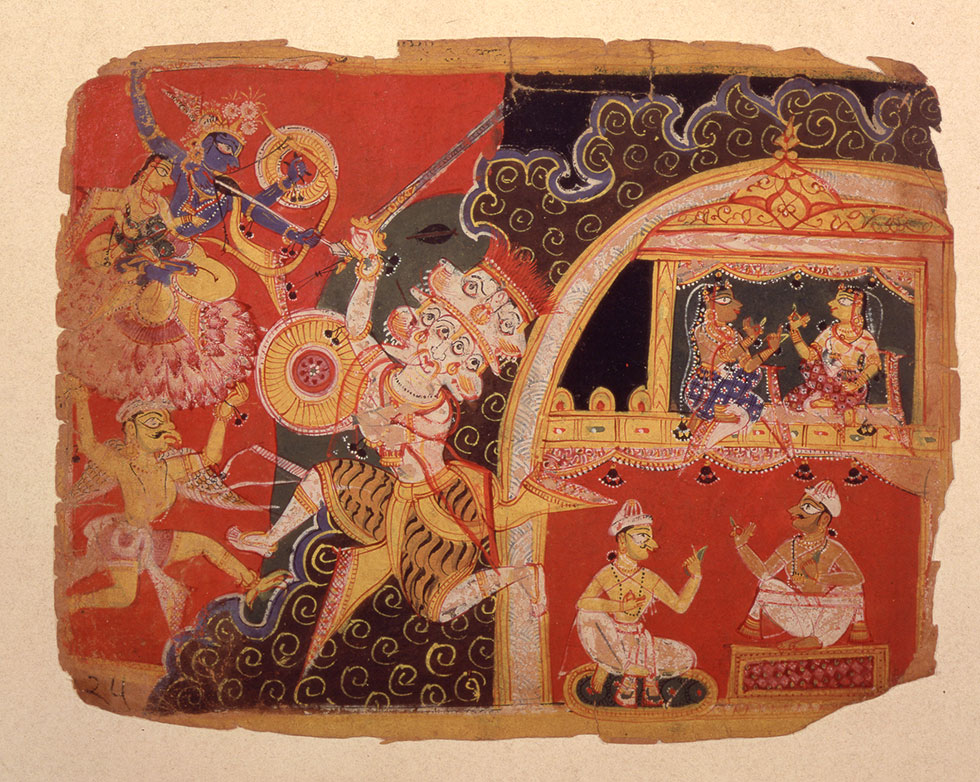

Krishna and the Fire-Headed Demon Mura. Folio from a Bhagavata Purana manuscript. India, Rajasthan or Uttar Pradesh. About 1500–1540. Opaque watercolor and ink on paper. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.55. Photography: Susumu Wakisaka, Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo

This folio comes from an illustrated Bhagavata Purana that was produced in northwest India. In the very popular Book Ten, the god Krishna, who like Rama is one of the god Vishnu’s avataras, is the primary protagonist. In this illustration from that book, Krishna, easily identified by the blue color of his skin, is at battle with Mura, a five-headed demon. The bird-man Garuda holds Krishna, who aims his bow and arrow at Mura as the demon theatrically leaps over the moat surrounding the city of Pragyyotishapura. To the right inhabitants of the city conduct their daily routines unaware of the nearby fight. The name Sa. Nana is written at the top left of this page, which may refer to the names of the two brothers who commissioned the manuscript.

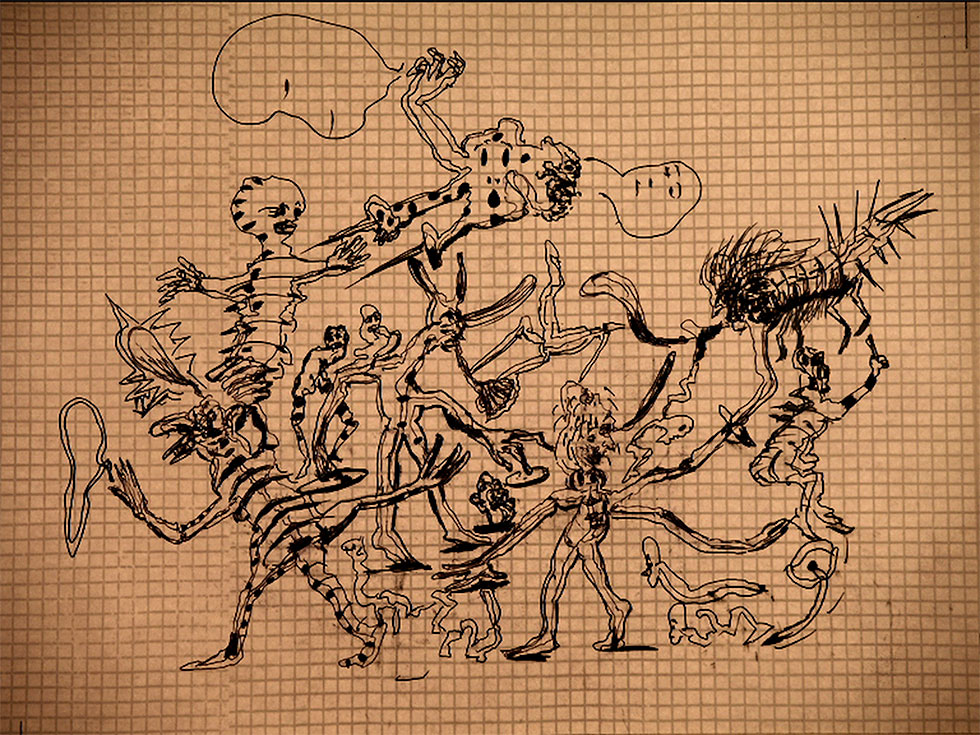

Nalini Malani (b. 1946 in Karachi, Pakistan; lives and works in Mumbai, India, and Amsterdam, Netherlands). (Video still) Penelope, 2012. Single-channel stop-motion animation. Duration: 1 minute. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Katherine and Rohit Desai, 2014.9. Image courtesy of artist

Nalini Malani is one of the most important first-generation new media artists in India. Her prominence was recognized early on through her inclusion in the landmark exhibition “Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions” at Asia Society Museum in 1996. She has created a unique visual language through her drawings, videos, and most notably her video/shadow play installations. Her works have a strong theatrical element and incorporate themes from ancient Greek and Hindu mythology as metaphors for contemporary events. This video sketch references the story of Penelope from Homer’s Odyssey, and how she wove and unraveled her burial shroud in Odysseus’s absence in order to avoid her suitors, alluding to the power of female resourcefulness. Malani’s deft use of stop-motion animation highlights the artist’s foundation in drawing. The video was commissioned by dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012 to complement her video/shadow play installation In Search of Vanished Blood.

Artists have often looked to past artistic traditions for inspiration. The influence of the past can take many forms—as merely an aesthetic reference to historical works, or in other cases an internalization and implementation of traditional processes or ideas. The selection of photographs from Cang Xin’s “Communication Series” creates a link between the present and China’s rich cultural past by the representation of the artist’s physical interaction with traditional objects. By documenting his actions, Cang Xin represents a desire to better understand history through this literal interaction with the past. The practice of borrowing or appropriating traditional art forms is manifest in a more comprehensive manner in the work of Ah Xian, another contemporary artist in this section. Ah Xian draws inspiration from ancient art in his “China China” series. He produced his fine ceramic busts in collaboration with artisans based in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, which was an imperial porcelain factory established in 1402 by the Ming-dynasty emperor Jianwen (reigned 1399–1402). Chinese emperors found the translucent white porcelain body and its decorative possibilities irresistible. Jingdezhen became the center of China’s porcelain production in the early Ming period, and it continued to thrive into the Qing period when export wares for Europe became important for trade. The techniques, styles, designs, and glazes one sees in Ah Xian’s busts are evident in Ming and Qing ceramics from Jingdezhen and traditional landscape painting.

Dish. Jiangxi Province. Ming period (1368–1644), Zhengde era (1506–1521). Porcelain with overglaze yellow enamel (Jingdezhen ware). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.180. Photography by Lynton Gardiner, Asia Society

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, altar vessels that had their origins in bronze forms, such as stem cups and censers, were often made of porcelain. Monochrome wares were specially produced for the four altars used for imperial ceremony and sacrifice. For example, brilliant yellow ceramics were used at the Altar of Earth (diqitan), and deep blue ceramics were used at the Altar of Heaven (tiantan). This dish has a six-character Zhengde reign mark on its base.

Ah Xian. China China – Bust 57, 2002. Porcelain with low-temperature yellow glaze and relief. Asia Society New York: Asia Society Museum Collection, 2002.37. Photography by Synthescape

Ah Xian’s “China China” series was inspired by the artist’s desire to use Chinese culture as a source of inspiration to create new cultural forms. The title of the series refers to not only a geographical location but also to western associations to the artistic medium of “Chinese porcelain” through its pervasive historical connotations with China, and specifically Jingdezhen, due to the country’s role as the primary producer of export porcelain to the West from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries. This relationship to place is further emphasized by the fact that the artist uses Chinese models exclusively to fashion his busts. The traditional patterns that decorate the surface of the sculptures are largely taken from pattern books used by commercial porcelain factories. Bust 57 is inscribed with traditional Chinese landscape motifs. Since 1999 the artist’s porcelain sculptures have been exclusively fabricated by the artisans working at the kilns in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province. This collaboration blurs the boundaries between the applied and fine arts. More recently he has expanded to working with traditional cloisonné, lacquer, jade, horn, and bronze decorative arts techniques to create his figures.

Wang Gongxin (b. 1960 in Beijing, China; lives and works in Beijing). Always Welcome, 2003. Two-channel stop-motion animation with sound; four monitors. Duration: 1 minute, 16 seconds. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Mitch and Joleen Julis, 2015.9. Courtesy of the artist © Wang Gongxin

Wang Gongxin is considered one of the fathers of video art in China and was instrumental in introducing installation art to China in the 1990s. This humorous video installation illuminates the shifting meaning and associations of traditional Chinese cultural artifacts in a globalized world. Wang’s “stone lions” play off the disjunction between the West’s kitschy associations with these symbols and their longstanding representation of protection and wealth in Chinese culture. A pair of seventeenth-century porcelain Guardian Lions found elsewhere in the gallery emphasizes this departure from tradition. Lions are not native to China, but imagery of lions and even live lions were introduced to the country from abroad. In China there is a long tradition dating from as early as the third century C.E. of creating pairs of guardian lions. To this day stone lions are found guarding the entrances to official buildings and temples. Often the male lion of the pair, which is placed on the right, has an ornamental ball under his left paw. Similarly, the female can be distinguished by the cub under her right paw. Wang’s update of the motif through movement and sound is meant to directly engage the viewer and the friendly demeanor of his lions neutralizes the confrontational attitude that these protective sculptures were originally meant to convey.

Two Lion-Dogs. Japan, Saga Prefecture. Edo period (1615–1867), late 17th century. Porcelain painted with overglaze enamels (Arita ware, Kakiemon style). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.238.1-2. Photography by Lynton Gardiner, Asia Society

This pair of large ferocious-looking, Chinese lion-dogs, one with its mouth closed and the other with its mouth open, is elaborately decorated with multi-colored dots covering almost the entirety of their bodies. Japanese lion-dog figures, imported from Chinese sources, were generally used as guardians at entrances to Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. However, these examples illustrate how imagery continues to transform with cross-cultural engagement. Colorfully decorated porcelain statues like this pair of lions were often exported to Europe, and illustrate the extravagant (secular) taste of late seventeenth- to early eighteenth-century Europeans more than that of contemporary Japanese.

In East Asia nature has long been closely associated with spiritual or divine power and sacred sites, like Mount Fuji and Kumano in Japan, have been popular subjects for artists. Both Shinto and Buddhist deities are associated with these sacred sites and there are ritual ceremonies that honor these places and the deities connected to them. Over time, religious practices associated with Shintoism and Buddhism became integrated into the larger culture. Contemporary artists, like Mariko Mori, often appropriate religious rituals and iconography to create performance-based projects that emphasize the universal nature of spirituality and the importance of consecrated sites as places for reflection and transcendence within Asian and western cultures alike. Her video, Kumano, references Shintoism and Buddhism, as well as the Japanese tea ceremony.

Historical works from the collection provide allusions to the traditional notion of sacred space in Japan, which encompasses not only nature, but temple complexes and tea houses. These objects give a sense of how, like the artists of the past, Mori has been inspired by spirituality, nature, and ritual, but has created something innovative with the help of new media.

Attributed to Gekko (Chinese, Yue Hu). Byakue Kannon (White-robed Kannon). Japan; Muromachi period (1392–1573), late 14th–15th century. Hanging scroll; ink on silk. Overall H. 72 3/8 in. (183.8 cm). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3d Collection, partial gift of Rosemarie and Leighton Longhi in honor of Sherman E. Lee, 1998.1 Photography by Lynton Gardiner, Asia Society

Images of Avalokiteshvara, or Kannon in Japanese, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, seated on a rocky outcrop overhanging turbulent water appeared in China around the tenth century, inspired by textual references to Mt. Potalaka, his abode located off the south coast of India. A development of this theme, in which he is clothed in white robes, began to appear in the twelfth century and was favored by Chan, or Zen, monks who brought this imagery to Japan. Although Indian Buddhist sources describe Kannon as a male being, depictions in both China and Japan became increasingly androgynous over time. Religious literature developed in Japan after the introduction of Buddhism described the Buddhist origins of local Japanese deities (kami), thus appropriating them. According to such attribution of origin, the Shinto deity associated with the Nachi Waterfall at Kumano, Fusumi or Musubi no Kami, is identified as Kannon, in his eleven-headed, thousand-armed form. In her video, Kumano, Mariko Mori appears in the guise of a Shinto deity at the Nachi Waterfall.

Mariko Mori. (Video still) Kumano, 1997–1998. Single-channel video with sound; Sound by Ken Ikeda. Duration: 8 minutes, 50 seconds. Asia Society, New York: Purchased with funds donated by Carol and David Appel, 2009.3. Courtesy of Mariko Mori Studio, Inc.

Kumano has been revered by Shinto and Buddhist devotees as one of the most sacred locations in Japan and has attracted pilgrims since the eighth century. Mariko Mori was inspired to create this work after a visit to Kumano in 1997. The site serves as the backdrop for the artist to take on the persona of three spiritual deities: a forest fairy, a shaman performing a Shinto ritual dance, and a futuristic hostess who performs a traditional tea ceremony in a Buddhist temple. These personas respectively signify the past, present and future and allude to the evolving history of the site in relation to the development of organized religion in Japan. Through her use of video technology, Mori illuminates the transcendental forces of nature and the role tradition and the past play in the development of the present and future.

Nonomura Ninsei (Japanese, circa 1574–1660/66). Tea Leaf Jar. Japan, Kyoto Prefecture. Edo period (1615–1868), mid-17th century. Stoneware painted with overglaze enamels and silver (Kyoto ware). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.251. Photography by Synthescape

Nonomura Ninsei’s beautifully enameled ceramics, especially large tea-leaf storage jars like this piece decorated with a group of haha (a mythical Japanese bird similar to a crow), formed an essential part of contemporary Kyoto tea-ceremony culture. One of only a handful of seventeenth-century potters with name recognition, Ninsei operated an extremely successful kiln in Kyoto called Omuro and catered primarily to important patrons in Edo (present-day Tokyo). His seal is imprinted on the unglazed base of the jar.

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). South Wind, Clear Dawn (Gaifū kaisei). Japan. Edo period, early Tempō era, ca. 1831–33. Woodblock print; color woodblock print; ôban yoko-e. Series: Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji (Fūgaku sanjūrokkei). Signed: Hokusai aratame Iitsu hitsu. Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudō). Asia Society, New York: Asia Society Museum Collection. Purchase, 2015.12. Photography by Bruce White

In this work, Hokusai captured the sacred Mt. Fuji as it takes on a red color at dawn, reflecting the rays of the rising sun. Mt. Fuji, like Kumano, the site of Mariko Mori's video in this gallery, is one of a number of sacred Japanese sites with connections to both Shinto and Buddhist traditions that are popular pilgrimage sites and have inspired artists with their great beauty and spiritual associations. This recent addition to the Asia Society Museum Collection is a rare, second-state print from Hokusai’s famed Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji woodblock print series. Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) was a household name in his own time in Japan and became world-renowned for his prints within fifty years of his death. His name is synonymous with dramatic landscapes.