Artists Tackles History of Anti-Chinese Discrimination in Indonesia

During the height of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998, Indonesia plunged into turmoil as food shortages and mass unemployment led to widespread protests and riots. And, as they had been many times during past crises, the country’s ethnic Chinese population was scapegoated.

Under the authoritarian rule of President Suharto’s New Order, a raft of discriminatory laws ensured that ethnically-Chinese Indonesians — who made up about 2 percent of the country’s population — remained second-class citizens. This exacerbated hatred of the group that stretched back centuries. So when the economy took a turn for the worse, the ethnic Chinese became a convenient target. As riots reached their zenith on May 14, 1998, Chinese-owned shops were ransacked, scores of women were raped, and over 1,000 were killed. In one particularly heinous incident, a mall was set ablaze, killing hundreds that were trapped inside.

Numerous reports emerged that military forces had allowed, or even instigated, the violence — some believe at the behest of Suharto himself. But within a week, the strongman was forced to resign, ending his nearly three-decade rule and beginning the more politically open and liberal Reformasi period.

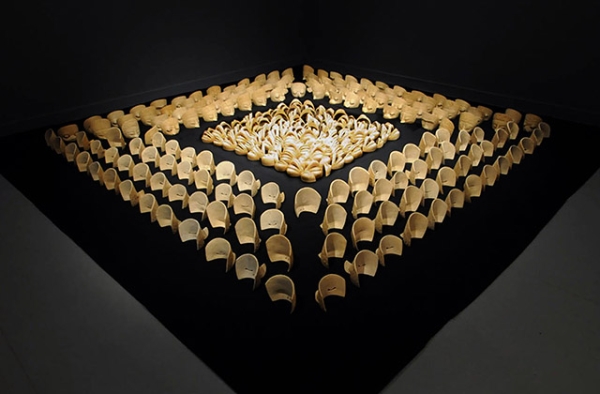

It was during this time that the Chinese-Indonesian artist FX Harsono captured the sociopolitical upheaval and subsequent political transition through a number of visual and performance artworks. Among them were Burned Victims, which memorialized those who had perished in the Jakarta mall fire, and Blank Spot on My TV, which lampooned political figures in the waning days of the New Order. More recently, Harsono created works reflecting on other massacres of ethnically Chinese Indonesians in his country.

Some of Harsono’s works will be on display at Asia Society in New York through January 21 as part of the exhibition After Darkness: Southeast Asian Art in the Wake of History. In conjunction with the exhibition, the artist spoke with Asia Society about his Chinese-Indonesian identity and how it has encouraged him to use art to remind people of the darker chapters of his country’s history.

Why did you decide to do political art?

When I first started making art related to social and political issues, I was thinking about Indonesian identity. I wanted to talk not just about local issues but national issues. Some artists try to find Indonesian identity using traditions. But as a young artist at the time, I didn't agree with that because the traditions in one area don’t represent all of Indonesia. So how to represent Indonesia? I realized that social and political issues were the same everywhere in Indonesia under the Suharto era, where a lot of people were suppressed by the military.

But after that, I realized that art can also mean being part of social activities. So I started to participate in NGOs, activism, and labor activities, and discussed social problems so my art could be stronger and more useful for people. Before I make a piece of artwork, I do research and become a part of the sociopolitical issue myself. Now I do a lot of research for artwork using issues related to Chinese people in Indonesia. I don’t just read books but also do field research to find mass graves, some eyewitness, and survivors. For me, it's very important for the artist who engages with social and political issues to not just look from the outside but become part of the issues.

How much discrimination did you experience growing up as ethnically Chinese in Indonesia?

From when I was a child, I realized I was Chinese and endured a lot of discrimination from indigenous people. People would say I’m not Indonesian, even though I was born in Indonesia. My parents aren't even 100 percent Chinese and I can’t speak Mandarin, so I wondered why they called me Chinese. Then when I started to grow up, I had to prove Indonesian citizenship for certain things, like in court. Others didn’t need to — they just said they were born in Indonesia — it was only the Chinese in Indonesia who had to prove this, which was part of the discrimination by the government. But now all children born in Indonesia automatically become Indonesian.

How did the 1998 anti-Chinese violence in Indonesia affect you?

In 1965 in Indonesia, there were a lot of people killed because they were deemed communists. That of course was traumatic for me, then it happened again in 1998. In 1965, Chinese weren't the specific target for the violence, but in 1998 the Chinese became the target. Chinese shops and houses were burned and Chinese women were raped. Of course, I felt scared because the political situation created chaos in Indonesia — mostly in Jakarta and some cities in Java. I became angry because of this and I questioned a lot — like why do Chinese always become a target during social and political change in Indonesia? I think everywhere, when people want to create social and political change, they use racial or religious minorities and women as a target to capitalize on the situation.

That time around May 14, 1998, the situation in Jakarta was very chaotic and a lot of people like me didn’t want to leave their house or neighborhood. Every night all the men guarded our housing area because the situation was so chaotic at the time. On May 17th, my mother passed away in my hometown in East Java, so I had to go back there. I went to the train station in the city so I could go to my hometown. The city was very quiet by then — it looked like no one wanted to go out. The situation was scary.

There have been many instances of Chinese being targeted and killed en masse in Indonesia going back to 1740. Do you worry there's a certain continuity, and that it could happen again?

Yeah. A lot of Chinese also wonder who can guarantee that this situation won't happen again in the future. I'm an artist, so I can only worry about the situation, but I must do something through my work, and I also made a documentary film to show this dark history. I use my art to teach society so this doesn’t happen again.

How has your art been received in Indonesia?

Up to now, I haven't had any problems. Most people, when they see my work they understand — yeah we have a lot of problems and must not do this again. Just a few people are anti-Chinese and still use discrimination as a political issue. But I believe a lot of people now realize that Chinese in Indonesia are part of our family, our neighbors.