Writing and Technology in China

By Irene Leung

August 2008

Early Writing Technologies

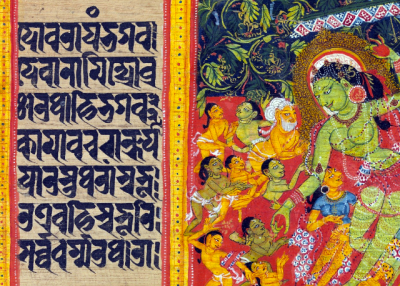

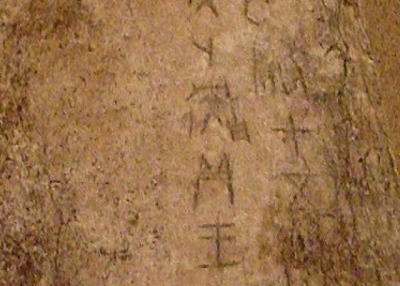

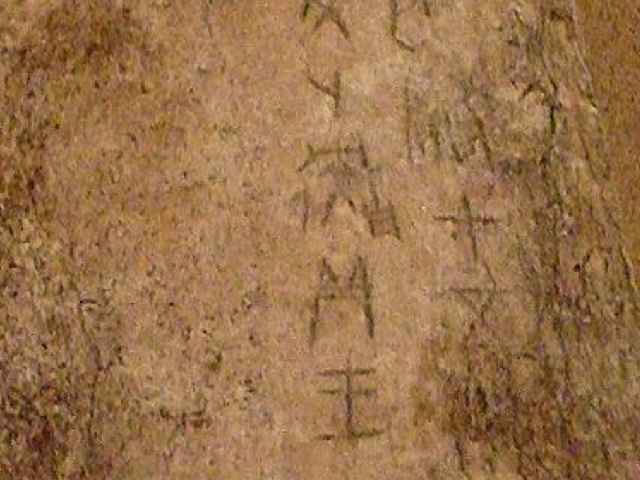

The earliest writings in China were found on ox scapulae, tortoiseshells, and bronzes during the Shang dynasty. Dated from around 1400-1200 B.C.E, the inscriptions on bones and shells-called "oracle bones"-recorded divination used by the Shang royal house. The words were carved with a stylus, some were written with brush and ink made of lampblack or cinnabar. On bronzes, inscriptions were cast on sacrificial vessels, ritual bells, and seals. These inscriptions range from a few to as many as five hundred characters.

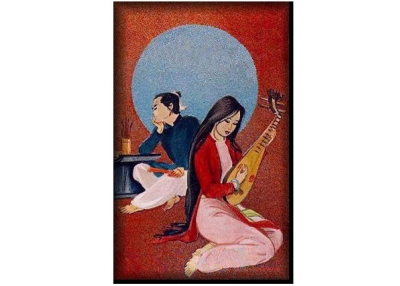

The brush pen was used as early as the seventh or sixth century B.C.E. The holder is made of bamboo, and the tip is made of wolf, rabbit, or goat hair. Brush-point size depends upon its use in executing different styles of characters. The brush was used in conjunction with ink, a permanent black pigment that could not be washed out after being applied. The basic ingredients for ink are pine soot or lampblack and glue (as a binding agent) with any other miscellaneous additives, such as gold flakes, musk, and camphor. Ink is kept as a solid, dry stick until ready for use. A writer then grinds the dry ink stick against an "inkstone," a polished and often decorative piece of stone with a shallow bowl carved into one end. Water is added to the shallow bowl, while the writer moves the inkstick in a circular motion to form dark, liquid ink. When a desired blackness of ink is reached, the writer then uses his or her brush to lift the ink directly from the inkstone. Ink is judged by its insolubility, luster of pigment, and hardness.

Archaeological evidence shows paper was invented around the first century B.C.E. By the third century C.E., paper was already widely used for making books. Since paper was made of readily available materials, such as raw hemp and tree bark, it was inexpensive to produce.

The four implements of brush, ink, inkstone and paper, were later dubbed the "Four Treasures of the Scholar's Studio." The scholar-official class, an outgrowth of the bureaucratic government, used these treasures as tools of communication and self-expression through calligraphy.

Chinese Books and Printing Technologies

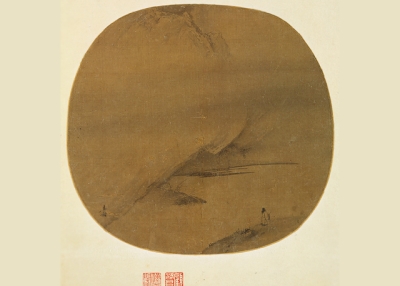

Chinese books began as thin slips of bamboo or wood connected by thongs and used like paged books or scrolls. Recovered from tombs, the oldest of these dates back to third or fourth century B.C.E. They were used for official documents, private letters, calendars, laws and statutes, prescriptions, literary texts, and miscellaneous records. These bamboo or wood documents were sometimes considered drafts, the final editions were written on silk, which had been used for writing since the sixth or seventh century B.C.E. Since silk provided larger continuous writing surfaces that could be tailored to the needs of each patron, it was used for maps, illustrations, and more formal inscriptions, such as religious sacrifices, quotations of kings, and achievements of great statesmen and military heroes. Surviving silk fragments also show that this material was used for letters because it was lightweight and easy to transport.

Printing developed from engraving on stones and metals as well as taking ink rubbings from stone reliefs. Ink rubbings are impressions of relief designs of text or pictures. A sheet of paper is laid on the stone and moistened with water. The paper is then squeezed against the surface and pressed lightly into every depression with a brush, and ink is applied to it with a pad. When the rubbing is peeled off and pressed flat, the parts of the paper where there are characters or pictures will appear white, while the rest will appear black.

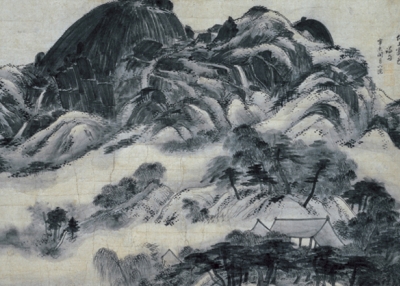

Woodblock printing uses a similar method and is a very simple and inexpensive process. A sheet of paper upon which text has been written in ink with a brush is inverted and pasted on a wooden tablet. An engraver then carves the tablet where the parts of the paper are white. As a result, only the parts bearing characters (in reverse) stand out in relief. The printer then brushes ink on the printing block to which blank sheets of paper are pressed. A skilled printer could turn out as many as 1,500 copies a day. Technically, a single block could be used to print thousands of copies, though most editors ran a few hundred copies.

Woodblock printing began to replace hand copying around 700 C.E. It grew out of religious demand for copies of Buddhist and Daoist scriptures and secular demand for the reproduction of classical text used in the civil service examinations. The existence of these examinations, based on the study of topics such as philosophy, history, and literature throughout the history of premodern China, assured the primacy of print culture.

The Song dynasty (960-1279 C.E.) saw a great proliferation of publishing. Government offices, schools, monasteries, private families, and private bookshops participated in the printing business. The advent and spread of commercial printing transformed popular culture and society. Published books covered a wide range of topics and interests, including history, geography, philosophy, poetry and prose, divination, archaeology, scientific and technical writing, and medicine. Movable type was invented in the mid-eleventh century. It was based on a principle of assembling individual characters made of fired clay to compose a text that would then be glued onto a plate to create a printing block. Common characters needed twenty or more types in case many were called for on the same page. Characters not being used were kept in wooden cases, according to their rhyme group.

Movable type did not prove to be popular. As opposed to Europe, where movable type was suitable for alphabetic languages with limited numbers of symbols, China, where the number of unique characters in a book might reach into the thousands, found it less practical and cost-efficient. A printer would have to stock from 20,000 to up to 400,000 character types in order to meet the demand of a book-a tremendous initial investment. The printer would have to make hundreds of thousands of copies in order to make a profit. Therefore, printing from movable type compared very unfavorably with the low cost of woodblock printing. A printer could choose to make under a hundred copies of an edition. The block could then be stored for printing again at a later date, depending on demand.

Because the written language was standardized, book publishing was not affected by regional dialects. Since rural areas and urban sectors were less sharply differentiated than their counterparts in premodern Europe and the literate population resided both in the countryside and the cities, book publishing flourished in smaller locales as well. Expanded education and increased economic prosperity in the sixteenth century contributed to an even greater rise in the demand for books. Furthermore, there were more educated individuals who wanted to work for the state bureaucracy than there were available positions. Failed examination candidates made up a large literate social class by the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 C.E.). In addition to the scholar-officials, these individuals became consumers and producers of print culture.

Modernization, the Press, and Public Opinion

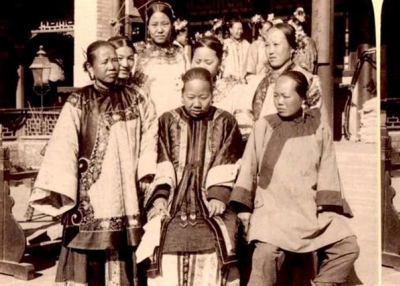

At the end of the nineteenth century, European missionaries and businessmen introduced mechanization and various printing forms. During this time, political information and new ideas were disseminated exclusively through print. At first government edicts were printed and circulated throughout the empire to several tens of thousands of local officials. Later, sensational news was reported on news sheets printed irregularly in the cities. The papers were first bought for entertainment. Soon timely news about political events, war, and peace negotiations spurred expansion of newspaper printing.

During this period, treaty ports were set up by Western powers in coastal China. Some periodicals were sponsored by missionaries but written by Chinese editors. These weeklies or monthlies also began to report international news. With the expansion of readership, modern printing machines became essential to the rapid production of widely circulated periodicals. This nationwide print culture gradually gave the educated class a greater sense of national identity. They also became aware of the press's potential to educate and mobilize the people against the central government.

Following the overthrow of the Qing dynasty, the Republic of China was established in 1911. The vision of a modern society began to be put forth in a large number of newspapers and periodicals. These were often written in simple vernacular language, rather than in classical Chinese, which had been the language used in early newspapers. The articles addressed a range of social and cultural problems, bridging class as well as regional and occupational lines, drawing millions together.

By the 1930s the government continued to face the enormous task of national reunification and economic reconstruction. It began to censor newspapers, journals, and books in order to crack down on Communism. Some intellectuals took their ideas underground. These activists looked toward woodcut as a swift, inexpensive means of creating graphics or pamphlets to spread their ideas. The prints celebrated the courage of students who evaded the police or protested against censorship and publicized the plight of the urban and rural poor.

After the Communist Revolution in 1949, the Party controlled newspapers and journals through state-owned enterprises. For the next decades the print media was used to publicize government policies and propaganda during collectivization movements and ideological campaigns. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Red Guards turned to a more spontaneous medium to denounce alleged counterrevolutionaries. They wrote "big character posters" and posted them outside people's houses or schools to publicly expose their alleged crimes. By the end of the Cultural Revolution, however, the role was reversed. The same print media in turn kept the bureaucracy in check through journalists who investigated abuses of government units and officials. These media also became a forum for citizens to voice grievances. They circulated stories about the horrors and tragedies experienced by many during the Cultural Revolution. This criticism and self-criticism stimulated new debates and reflections on China's past and its future prospects.

Economic innovation and growth in the 1980s began to raise questions of political reform beyond the basic principles of the Chinese Communist Party. While the government was able to control print media, and to a certain extent radio, television, and satellite access, the advent of telecommunication technologies and the Internet revolution in the 1990s make it increasingly impossible for the government to control and monitor news and public opinion. Despite the fact that Internet access is still available only in urban areas, it has enjoyed spectacular success in China in the last five years. One recent figure shows that the number of Internet users grew to 8.9 million in 1999 and the Chinese government predicts that by 2003 Internet use will reach 20 million. Most Internet users are people between the ages of 20 and 40. About 85 percent of users are male, and many earn above average income. They use the Internet to find out about news and current affairs as well as for entertainment. Technological innovation has not only provided faster and easier access to print media, it has transformed people's relationship to each other and the government's relationship to its constituents.