Massacre at Nogun-ri

At the beginning of the Korean War, US Army ground troops of the 7th Cavalry executed civilian refugees over the course of four days. Fifty years after the fact, the world is learning about the massacre and trying to understand how crimes against humanity could occur, even during times of war.

Background to the Korean War: 1945-50

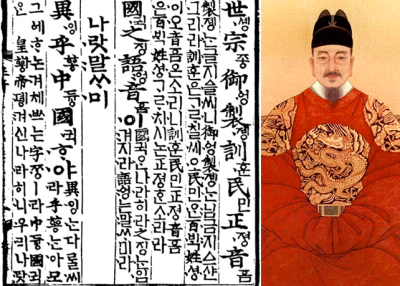

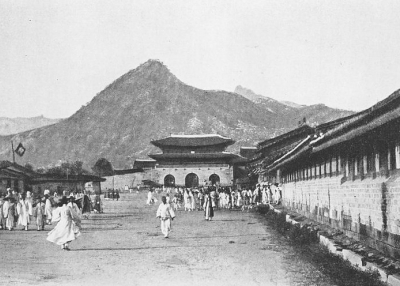

Japan’s 35-year colonization of the Korean peninsula came to a close with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that capped World War II. Japan, preparing for its inevitable removal from the peninsula, sought to install a temporary governing structure in Korea. The approach of the Soviet military from the north led the colonial government to believe that the peninsula would ultimately come under Soviet control. While long years of colonization had produced undercurrents of wide-ranging political sentiments, the conservative Japanese ultimately tapped a popular leftist, Yo Un-hyong, to oversee a temporary administration, predicting that his leftist leanings would win a Soviet nod. On August 15, 1945, the day of Japan’s surrender to the Allies, Yo accepted the colonial government’s proposal. His contacts and popularity aided him as he quickly set up a Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence (CPKI). By September, the CPKI had formed the Korean People’s Republic (KPR) and within three months had established offices countrywide, from the township level on up. It was a far more vigorous and popular governing force than the Japanese had expected, but they had been left with hardly a choice in the matter, having freed their political prisoners and acceded to other demands made by Yo, just to convince him to take the job.

The Soviet and US leaderships agreed to jointly accept the Japanese surrender in Korea and to each oversee one half of the peninsula—divided at the 38ºN parallel—during a transitionary phase of no set duration. Communist Koreans accompanied the Soviet party to this task in the north, where they influenced the leftist KPR administration. On the other hand, the US team (with few Korean personnel) arrived later in Seoul, and were greeted by Japanese officials’ rumors that Korean communists planned upheaval and sabotage. So, with little understanding of the changes already begun by the KPR, such as guidelines for land redistribution and labor reforms, the US Army broke up the KPR’s nascent networks in the south to set up its own government. To make matters worse, the US invited Korean officials who had been complicit with Japanese colonial rule to participate in the new Army-led government. The move put them directly at odds with the KPR (whose policies, such as land redistribution, sought to eliminate the inequities of the colonial period), and with the public-at-large (who viewed the reinstated officials as cronies and collaborators of the Japanese). Though the reinstated officials claimed to be democrats in a newly established political party, the US track seemed rather to be leading back to foreign, conservative colonial rule in an increasingly divided Korea.

In 1947, with the Soviet-US Cold War intensifying, with no progress made toward Korean reunification, and with hope snuffed out for its joint trusteeship (envisioned as being shared between the US, the Soviet Union, Britain, and China), the UN, at the urging of the US, established a temporary commission to supervise elections in Korea. However, the Soviets barred the UN-initiated election in the north, and so in 1948, in the south, Syngman Rhee, an exiled septuagenarian devotee of independence and a forty-year resident of the US, was elected the first president of the Republic of Korea (ROK). In the north, the Soviets followed up by supervising a separate election naming Kim Il Sung, a glorified thirty-six-year-old hero of anti-Japanese guerilla warfare in Manchuria and a supporter of the Soviets, the first premier of the new Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Both governments claimed sole legitimacy to govern Korea, and this would become the discordant North-South duet for the next 50 years.

Early Weeks of the Korean War

By the end of 1949, both the Soviets and the US had withdrawn from Korea’s political scene, leaving the cleft nation to its own devices. In the south, leftist guerillas were quashed; in the north, Korean communists arrived home from the civil war in China; and along the 38°N parallel, the armies of the two sides often skirmished. On June 25, 1950, war erupted when North Korean forces, backed by the Soviets, invaded all along the 38°N parallel. South Korean and US forces rapidly retreated southward. By August, North Korea would have nearly the entire peninsula under its control. The arrival of UN forces in the south and later Chinese reinforcements in the north would wrest control back and forth. By the time of the reluctant truce signing on July 27, 1953 (Syngman Rhee swore he would unite the country or die trying), South Korean casualties would total 1.3 million, and North Korean casualties, 1.5 million.

In the weeks shortly after June 25, the speed of the North’s advance and of the South’s retreat left a wake of violence and devastation. Full knowledge of the events of those weeks can never be had.

Early on, political prisoners and, invariably, civilians were executed en masse by both sides. Seoul fell to the North by early July. South of Seoul, ROK forces killed 1,800 political prisoners (South Korean leftists) at Taejon, to prevent their collaboration with the advancing North. On July 20, North Korea seized Taejon in a siege that killed upwards of 5,000 South Korean civilians and around 60 US and ROK soldiers. In turn, southeast of Taejon at Dokchon, retreating ROK soldiers and police executed up to 2,000 South Korean leftists without trial, an atrocity photographed by US soldiers. (Soon afterward, US ambassador John Muccio urged Syngman Rhee to stop the mass executions). Disorganized, urgent retreats were incendiary. Many massacres were recorded; far more were, and still are, alleged.

Guerilla fighters aided the North substantially throughout the conflict. Around 3,000 guerillas died within the first month, and by the end of the war, 67,228 guerrillas would die. In comparison, 58,809 ROK soldiers, 33,629 US soldiers, and 3,330 UN soldiers were killed by war’s end.

It was amidst these circumstances of rapid movement and volatility that US troops killed Korean civilians at Nogun-ri.

Time Opens the Sluice of Memory: Nogun-ri

Nogun-ri was practically unheard of before the Associated Press’s report of the bridge massacre was published on September 29, 1999. The report earned the AP a Pulitzer Prize.

The Pulitzer did not protect the authors from criticism. The story’s main source, a US veteran named Edward Daily, was proven to be a fraud—he claimed to have been a machine-gunner at Nogun-ri, but in fact had been working as a mechanic elsewhere. Before he was exposed, Edward Daily had gone so far as to meet with Nogun-ri victims in Korea. The press reported accounts of tearful embraces and Daily’s passionate words of remorse and friendship.

Mistakes aside, the AP report, citing declassified military documents, carried implications of outright and deliberate war crimes, condoned if not ordered by the US Army. This prompted a full investigation by both the US and South Korea.

In fact, growing numbers of people had known of the massacre over the years. Following the 1953 truce, the repressive regime of Syngman Rhee forced civilians to silence their claims against the ROK and its US allies for war injustices. In the feverish year of 1960, when April saw a student-led revolution topple Rhee, survivors tried to file a claim for compensation, but efforts were thwarted when the military seized power in 1961. After the democratic presidential elections of 1993, survivors sent petitions to US officials and President Clinton.

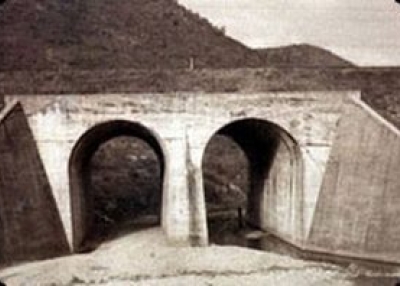

In a letter to President Clinton dated September 10, 1997, petitioners described the incident according to the recollections of victims. They described US soldiers evacuating them from several villages and leading them to a stream. Overnight, the villagers observed long lines of troops and vehicles passing in the direction of Pusan. At dawn, finding none of their previous night’s chaperones about, the villagers left the stream and began walking down the Seoul-Pusan highway with other evacuees. When they reached Nogun-ri, several US soldiers appeared, stopped the group, and instructed them to stand on the railroad tracks atop the bridge where the soldiers then searched them for weapons. The victims claim that the soldiers then radioed for an aerial bombardment and then fled. Soon, fighter jets arrived and strafed the group. Of those who were not killed, many escaped to the tunnel beneath the bridge, where for the next four days, July 26-29, soldiers fired at them. Those who survived the four days did so by using dead bodies as shields. US medics visited the group, but did not offer help; they merely checked out the situation under the bridge. The petitioners estimated that 400 died. Individual accounts included horrific details: a young woman plucking her dangling eyeball from a thin tether of nerves; another, surrounded by bleeding bodies, lapping at the ground to relieve her thirst.

After the initial shock of the AP story, people began seeking human logic behind the inhumane killings by looking for common elements in the stories of the veterans and survivors and by examining available evidence.

Guerillas had been known to infiltrate ROK and US positions disguised as civilians in white peasant clothing. Soldiers duly feared that guerillas were harbored among civilians, particularly during retreats, or when groups approached suddenly, or attempted to cross front lines.

Likewise, regarding refugee management, it was common practice to prevent them from crossing front lines and approaching troop positions. In a July 26 communications log, General Kean gave orders that all civilians moving around in combat zones would be considered unfriendly and were to be shot. The daily log notes that the ROK chief of police was to be summoned and informed of these orders, presumably so that the police could manage refugees accordingly.

Regarding strafing by US fighter jets, a CBS reporter uncovered a July 25 memo, written by Colonel Turner Rogers, entitled “Policy on Strafing Civilian Refugees.” The memo notes that, at the request of the Army, all civilian refugee parties that approached troop positions were being and would continue to be strafed. Several pilots’ logs noted the strafing of targets who were dressed in white peasant clothing, or who had loads of possessions and appeared to be civilians. Upon receiving orders that appeared to target civilian refugees or evacuees, many pilots questioned the choice of targets, and some claim to have refused. “[W]e didn’t have a system and communications network to control and coordinate air and ground operations,” said one pilot veteran.

While the circumstances of guerilla threats, unmanageable numbers of refugees, and questionable strafing targets could mostly be agreed upon, the charge lingered unresolved that soldiers on the ground had intentionally and under specific orders killed civilians.

More and more, veteran interviews corroborated that charge of intent. Several veterans recalled shooting the civilians at Nogun-ri, and up to 20 recalled having orders to shoot civilians (though neither these veterans nor the Pentagon investigators could figure out from whom or from which level of command the orders came). One veteran recalled shooting on his own volition, without orders, based on the belief that guerillas among the group would kill him if they were not completely eliminated. “We got orders to eliminate them,” said veteran Eugene Hesselman, recalling a similar event a week after the Nogun-ri incident. “And we mowed them all down. The Army wouldn’t take chances.”

In January 2001, the Pentagon wrapped up its yearlong investigation in its “No Gun Ri Review.” The Review opens matter-of-factly with the AP story and the Korean survivors’ accounts. It chronicles activities all around the bridge area. Aerial photographs and tactical maps uncovered in their “1-million document” study illustrate the report. While no remains or mass graves were detected in the area, the Review ultimately concluded that US soldiers shot unknown numbers of civilians at the bridge at Nogun-ri. The Review does not say that orders were given to do so.

As regards management of refugees, “The task of keeping innocent civilians out of harm’s way was left entirely to ROK authorities,” states the Review. In considering all the reported evidence, the Review assigned blame for the deaths to nearly every party involved—the US Army for shooting; the ROK for mismanaging refugee movement; North Korea for instigating the war, and their guerillas for masquerading as civilians; and the individual US soldiers for joining the Army, for moral decrepitude, and for murder. Though no one doubts the innocence of the civilians, some accounts suggested that soldiers returned fire after believing they had received small arms fire from the group.

Following upon the conclusion of their respective investigations, the US and ROK announced a “Statement of Mutual Understanding” on the Nogun-ri incident. The report states that at the time of Nogun-ri, refugee control was a “major concern.” Strafing could not be confirmed on July 26, as survivors had claimed, and none of the pilot veterans recalled the policy outlined by Colonel Rogers’ memo on strafing. Forensics, it reports, evidences US bullets in the wall of the bridge tunnel. However, it reports further that both US and Soviet munitions were found throughout the vicinity, widening the possibility that US soldiers may have thought they were returning fire received from the group (regardless of whether or not the soldiers had really received fire). The Statement concludes that US soldiers killed an “unconfirmed” number of civilians “during a withdrawal under pressure….” President Clinton offered an unprecedented apology for the deaths and announced that, in remembrance and honor of the victims, scholarships would be awarded and a memorial built at the site.

With the gist of the AP story affirmed—that US ground troops shot and killed South Korean civilians near Nogun-ri, July 26-29, 1950—the AP retained its Pulitzer. The reporters went on to develop the story into a book, The Bridge at No Gun Ri, introducing more actors and testimonies from the incident, and making severe point-by-point criticisms of the Pentagon’s investigation of Nogun-ri.

Survivors, their families, and advocate groups were not appeased by the show of cooperation and agreement between the two nations, or by the type of compensation offered up. On July 20, 2001, one of the survivors’ advocate groups staged a symbolic Korean War Crimes Tribunal in which the US was convicted, symbolically, of multiple counts of war crimes. In August 2001, lawyers were preparing a case against the US government on charges of violating the US Freedom of Information Act. The pivot-point for the continuing claims is compensation, and the net of grievances stretch beyond US involvement in Korea, to US involvement around the world.

While it’s questionable what good can come of these further measures, the evidence uncovered during the investigation shows not only that US soldiers killed civilians at Nogun-ri and elsewhere, in violation of numerous international treaties governing war—Geneva, Nuremburg, Hague, and UN human rights treaties—but that war crimes are more common and more close-to-home than people may have thought. It is not surprising information; even the disappearance of a few flight logs is not a major surprise. For the US, and other governments that enter conflicts in other countries, owning up to these crimes is a delicate operation, mixing public appeasement and foreign policy; for veterans, victims, and everyone else, they are a stark fact that some can neither face nor accept.

Works Consulted

ACKERMAN, Seth, “Digging Too Deep at No Gun Ri,” Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting. (Sept/Oct 2000). http://www.fair.org/extra/0009/nogunri.html

CUMINGS, Bruce, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. (New York: WW Norton, 1997): 185- 298.

ECKERT, Carter J., Ki-baik LEE, et al., Korea Old and New: A History., Korea Institute, Harvard University (Seoul: Ilchokak, 1990), 327-352.

GALLOWAY, Josepth L., “Doubts about a Korean ‘Massacre’,“ US News and World Report (12 May 2000).

HANLEY, Charles J., Sang-Hun CHOE, and Martha MENDOZA, The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War (New York: Holt, 2001).

LEE/ Tong-hui, “Thoughts on Nogun-ri Incident,” Korea Times (18 Jan 2001).

LOBE, Jim, “Nogun-ri Statement Fails to Douse Flames of Resentment,” Asia Times (16 January 2001).

MILLER, Jeffrey, “Korean War Crimes Tribunal: Searching for the Truth or Rewriting History?” Korea Times (20 July 2001).

“The Bridge at No Gun Ri," Korea Times. Book review.(10 Sept 2001).

MONTGOMERY, Alicia, “No Gun Ri: What They’re Saying,” Salon (1 Oct 1999).

SOLBERG, S. E., The Land and People of Korea (New York: HarperCollins, 1991),: 134-136.

SON Key-young, “Korea, US Show Wide Gap in Assessment of Nogun-ri Case,” Korea Times (6 Dec 2000).

Author: Elisa Joy Holland.