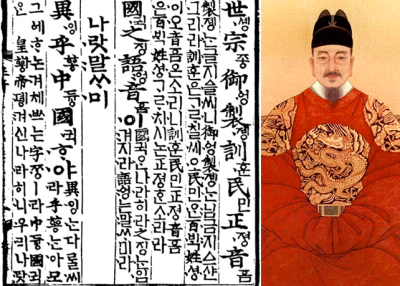

Religious Influence on Korean Art

What was the importance of landscape painting in traditional Korean art and culture? How did landscape painting develop in Korea? What are the distinctive characteristics of Korean landscape painting?

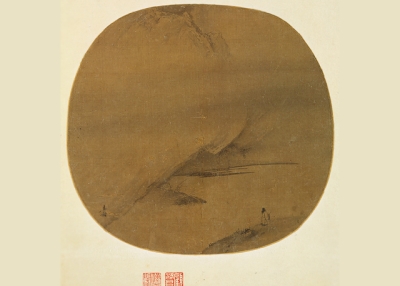

In Korea, landscape painting—rather than figure paintings or historical paintings as in the Western world—became the preeminent form in part because nature itself was considered sacred. Nature was seen as a living entity. It symbolized both an integral part of human life and a higher spiritual being. Such a conception of nature was shared also by China and Japan, with each culture developing its own variations of the philosophy and related rituals. Given the lofty ideals attached to it, transferring this vast and superior nature or landscape onto a two-dimensional surface posed a challenge to artists that in turn elevated the position of landscape painting.

Another reason that landscape painting became the superior art form in Korea was the dominance of Confucianism and neo-Confucianism, adopted from China. This philosophy prescribed, among other things, the cultivation of the intellect and humility. Translated into art, it meant that pictures of the human figure—the physical body, the mundane activities of humans, even historical episodes that focus on human activity or achievement—were secondary. Instead, landscape painting emerged as the means for exploration and expression of the intellect and of the larger world beyond human beings. Not until the eighteenth century, with the growth of genre painting, does figural painting become important in Korean art history.

Landscape painting did not take shape immediately. The earliest depictions of landscape in Korea, from the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BC–668 AD), appear as rudimentary background elements, not as an independent genre of painting. In the tomb wall paintings of the fifth century, for example, we see isolated mountains or trees depicted around figures in action, such as hunting. The human figures and the landscape put together comprise the whole.

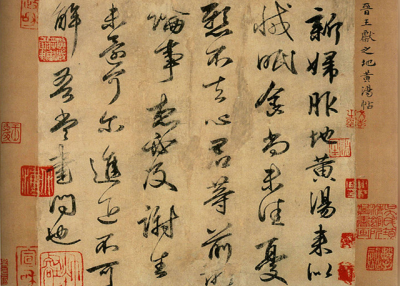

It was during the Koryo period (918–1392) that landscape painting—and painting in general—blossomed rapidly as an art form in its own right. This evolution paralleled developments in Song dynasty China (960–1279). Song and Koryo shared a close relationship of frequent diplomatic and cultural exchanges. As in the paintings of Northern Song, monumental landscape painting—pictures that portrayed colossal mountains and conveyed a sense of awe in nature—became popular in Koryo. Unfortunately, relatively few examples of landscape painting from this period survive, which makes it difficult for us today to assess fully its development and achievements.

Over the five centuries of Korea’s Choson period (1392–1910), the repertory of landscape painting expanded. There are also many more extant examples. Two schools of landscape painting were of particular importance during the Choson period. One was led by the fifteenth century court artist An Kyon. His landscape paintings adapted and transformed stylistic and conceptual elements of the old Northern Song landscapes and perfected a unique style. He played with innovative and striking compositions that challenged conventional notions of space and time within painting. His distinctive brushstrokes were copied and adapted by his followers who continued the tradition even after his time.

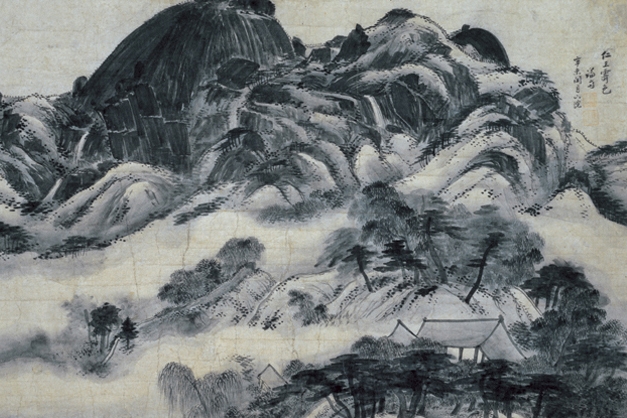

The other major school or style of landscape painting arose in the eighteenth century, led by the master artist Chong Son. His “True-View” landscape style revolutionized the whole concept of landscape painting in Korea. Until then, landscape painting was conceptually abstract: the landscapes depicted were usually not actual scenery or even the artists’ personal or emotional reaction to existing landscape, but rather nature as it was conceived in the artists’ mind. Chong Son’s paintings portrayed famous scenery in Korea— both previously painted sites such as the Kumgang Mountainan and other sites that had not been subjects of landscape painting—and did so in a way that presented the landscape as real, noble, and personal simultaneously. The achievement of True View landscape painting lies in its ability to evoke the essence of both native landscape scenery and native sensibilities.

Buddhism and Buddhist Art in Korea

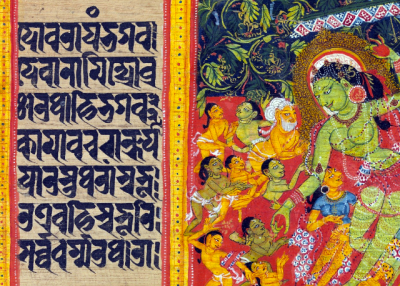

Buddhism, having originated in India, spread through almost the entire continent of Asia— and in the twentieth century, to the rest of the world—profoundly affecting the lives of both the converts and non-converts. The many different ways in which it has been adapted by the various cultures and societies attest to both the religion’s flexibility, as well as to the appeal of its fundamental principles. Buddhism was first introduced to Korea from China in the fourth century of the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BC–668 AD). It was subsequently adopted as the official state religion in each of the three kingdoms—Koguryo, Paekche, Silla—and remained the state religion through dynastic changes over the next seven centuries—unified Silla and Koryo—until the fifteenth century.

In Korea, the period between fifth and eight centuries represents a good case study of the early development and subsequent flourishing of Buddhism and Buddhist art. In particular, the development of Buddhist sculpture illuminates the changes in philosophy and taste. Early examples (from fifth and sixth centuries) of statues of the Buddha and other deities of the Buddhist pantheon evidence close iconographic and stylistic ties to their Chinese models: the elongated face, harsh facial features, sharp linear folds of the garment, stiff, central poses. This adoption of Chinese models was inevitable given both the early stage in the development of Buddhism/ Buddhist icons in Korea and also the nature of religious statuary, which dictates adherence to existing archetypes. By the seventh and eight centuries, however, Korean Buddhist sculpture had matured both conceptually and stylistically. The famous “Paekche smile” on the small Buddha statues of the Paekche kingdom, the elegant and individualistic representations of meditating (or pensive) Buddhas from the seventh century, and the technically and stylistically unsurpassed sculptures in the eighth century cave temple of Sokkuram are some of the most striking examples of the breadth of native development of Buddhist sculpture. Sokkuram and its sculptures, in particular, exemplify Korean ingeniousness and the essence of Korean style in Buddhist art. The cave, built as a dedication to the ancestors of a prominent politician of mid-eight century, embodied complex mathematical calculations and architectural genius. The statue of the main Buddha and the wall-carvings of Buddha's attendants manifest the ideal combination of the divine and the human—one that was rarely matched in Buddhist statuary of contemporary China or Japan.

It should be remembered that Buddhist art in Korea, as with religious art in many ancient societies, was more than purely aesthetic display. It also represented both the religious fervor and the political ambitions of the ruling class of the time. For the elite, Buddhism was not only a religious belief, a practical guide to life, and a means to salvation after life, but also a way of asserting political power and of subsuming the society under that power. The temples and iconic statues afforded the elite both visible public displays of its political presence and influence as well as a means of spreading and controlling the religion and the people. This is not to say that Buddhism and Buddhist art were the sole domain of the political elite. Buddhism did disseminate to virtually all levels of society, and objects of worship, such as statues, became accessible to various ranks of people (either in the form of regional or local temples with accompanying statuary or of small, personal shrines or icons in private homes).

After several centuries as the state religion, Buddhism was displaced by Neo- Confucianism in the Choson period (1392–1910). The latter was a philosophy based on the teachings of the ancient Chinese scholar Confucius, rather than a religion, but one that had wide-reaching influence in all aspects of public and private life in Choson society. Buddhist worship, as well as the production of Buddhist icons persisted in the provinces, away from the capital. Today, Buddhism continues to gain followers, but with increasing competition from other religions, both ancient and modern, including Christianity.

Genre Painting in 18th Century Korea

Genre painting developed in two directions in the Choson period (1392–1910). One was as visual representation of the culture and customs of Choson society and functioned as statepatronized pictures to be given as gifts to foreign dignitaries (especially Qing Chinese). The other branch of genre painting involved portrayals of daily activities of rural communities and began to develop around the seventeenth century. Paintings of the latter group were based on actual observations and depicted such mundane activities as farmers working in the fields, potters making pots, and women sewing.

This line of genre painting further matured and flourished during the eighteenth century. Such giants in the art world as Kim Hong-do (1745–1806) perfected genre painting and elevated its position within the canon of art. Kim’s works show ordinary people, male and female, young and old, engaged in everyday work or play. The figures are usually set against an empty or simplified background, so that it is the facial expressions and physical movements of the figures, along with the activity at hand—often involving the classroom, public sports or entertainment, or some type of manual labor—that become the focus of the picture. The paintings represent a moment in time, frozen, yet fully alive with all the sounds, actions, and emotions. Kim’s paintings are also often humorous—such as the scene of a boy being scolded by his teacher while his schoolmates giggle in the background—highlighting the light-hearted and playful side of life.

Another major artist of genre painting is Shin Yun-bok (1758–1800s). Unlike Kim, Shin painted scenes of aristocrat-scholars engaged in leisurely activities, such as boating or listening to musical performances. In addition, he is also well known for his pictures of courtesans (known as kisaeng in Korea). Many of Shin’s paintings involve a group of men on an outing with courtesans, semi-nude women bathing or laundering in the stream, or lovers’ secret rendez-vous, and are either subtly or overtly erotic. In both subject matter and erotic tone, they are clearly different from Kim’s works and are rather risque in the context of strait-laced and moralistic Choson society.

It is neither coincidental nor curious that the popularization of genre painting paralleled the rise of realistic and native-focused landscape painting (True View landscape) in the late Choson period. Both art movements emphasized actual observations, real scenes or scenery, and focused on either the people or landscape of the native land. Eighteenth century Choson Korea had turned its attention away from China, which had by then fallen under “barbarian” Manchu occupation, and looked to itself as the new cultural center of East Asia. This attitude allowed Koreans more freedom to examine and appreciate their native traditions. Moreover, a new, popular philosophical movement, called Sirhak or Practical Learning, pushed intellectuals and artists to explore practical aspects of life. These factors contributed to the growth of diverse trends in the arts and encouraged a greater range of artistic expression in both subject matter and style.

Author: Soyoung Lee.