Global Competence for Chinese Language Teachers

As a Chinese and Japanese language teacher, I’ve always had a secret antipathy for sushi and dumplings. It’s not that I don’t like to eat them. It’s just that, in my first experiences teaching these languages, I was often confronted by skeptical colleagues or parents wondering why these weren’t core parts of my curriculum. I dreaded the annual approach of Lunar New Year, when everyone would expect to see red lanterns outside my classroom and students performing lion dances.

I was once asked to show students a video of Chinese New Year customs that focused on a small rural village in central China. Toward the end of the video, a student recently arrived from Shanghai wandered into my classroom and sat in the back. At the end of the video, I asked him to tell the class what he thought, and he remarked with great surprise that he had never seen anything like those customs before and that young people in Shanghai just played video games during their New Year holidays!

The specter of the old “food and festivals” approach to language teaching haunts me to this day. I mustn’t overstate my case; I am not denying that dumplings and lanterns and chopsticks are a part of Chinese culture. But what about Tang poetry, Confucian and Daoist philosophy, the compass, paper, gunpowder, etc.? Or more contemporary developments like Chinese rap or rock music, fashion, and internet culture?

It’s a little like the feeling I get as an Italian-American, when I see “Italian” festivals that celebrate Pacino, DeNiro, and Sinatra—what about Dante, Leonardo (DaVinci, not DeCaprio!), and Galileo!? Aren’t Enrico Fermi and Arturo Toscanini Italian-Americans too?

It strikes me that a language teacher must be prepared to achieve three fundamental goals in the classroom: (1) to motivate students and cultivate in them a lifelong commitment to language learning; (2) to teach students the skills necessary to become effective language learners and to be able to recognize patterns in language and culture; and (3) to teach students to understand deeply the target culture in all its diversity, including both traditional and contemporary elements.

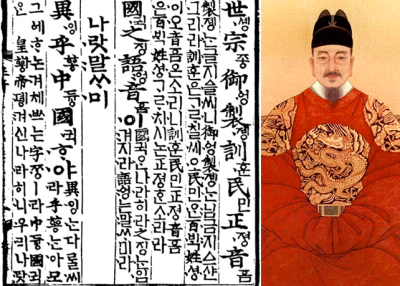

I have previously written about the first two of these goals, and often describe my approach to the second as teaching students to think like linguists and diplomats. As the field of Chinese language teaching and learning continues to expand and develop, it will be ever-more important to develop our teachers’ capacity to achieve the third of these goals. At Asia Society, we are currently completing a new online project called China and Globalization, for which I recently sat down with ten leading historians of China to talk about China’s diversity and its connections to the world throughout history. While many Americans—and many Chinese too, it must be said—continue to think of Chinese culture and civilization as being essentially monolithic, isolated, and unified, there is clear evidence that Chinese civilization has diverse roots, and that what we now call “China” has been involved in intense cultural, economic, and intellectual relations with other world regions from the earliest periods of history. That is, “China” cannot be understood separately from its interactions and connections with the rest of the world.

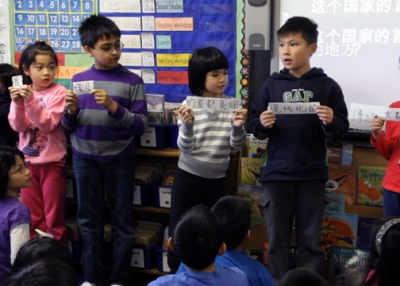

For teachers of Chinese, I think we need to add a new set of standards that go beyond language proficiency that include the ability to:

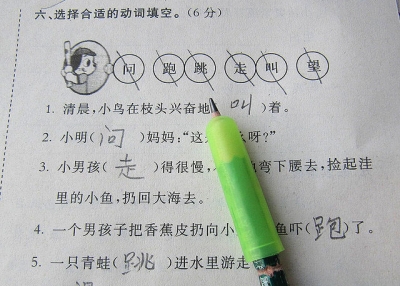

- Teach students about the structure of the Chinese language, as it relates to other world languages, including the unique characteristics of tone, characters, and particles

- Teach students about the latest developments and contemporary trends in Chinese culture and society, including the arts, film, literature, economics, politics, technology, education, etc.

- Teach students about the regional and cultural diversity of China, including geography, dialects, and minority groups

- Teach students about Chinese cultural history, including both high culture and folk culture

When looking at these daunting standards, I see how global competence for language teachers is something to aspire to and not easily achieved. And this realization underscores why I think global competence is so important. In line with both Confucian and Daoist approaches to education, I am a firm believer that it is the personal qualities of teachers that are most critical—good teaching can’t be mandated, legislated, or reduced to a written set of standards.

What you also discover in thinking all of this through is just how truly difficult is the task of teaching Chinese. Beyond the complexity of the writing system, there is also the incredible complexity of Chinese history and tradition.

But I think the benefits of building these kinds of competencies for teachers and students are obvious. Several years ago, a South Indian restaurant opened up in my neighborhood. Since I was one of his first customers, the owner chatted me up and asked what kind of work I did. At the time, I was preparing to open a new school and planned to serve as the principal. The owner looked somewhat dubious and told me in no uncertain terms: “You look much too young to be a school principal. A principal needs more life experience.” We continued to talk and the owner eventually revealed he was a Hindu temple architect back in Tamil Nadu and proceeded to tell me about the glories of the Tamil language and the antiquity of its literature. Having taken an entire course on the Sanskrit epic the Mahabharata in graduate school, I was more than happy to engage him on this topic. Eventually, the owner looked at me admiringly, saying, “You know the Mahabharata, you know everything. Okay, you can be a principal.” I walked out of the restaurant with the firm conviction that a little cultural knowledge can go a long way!