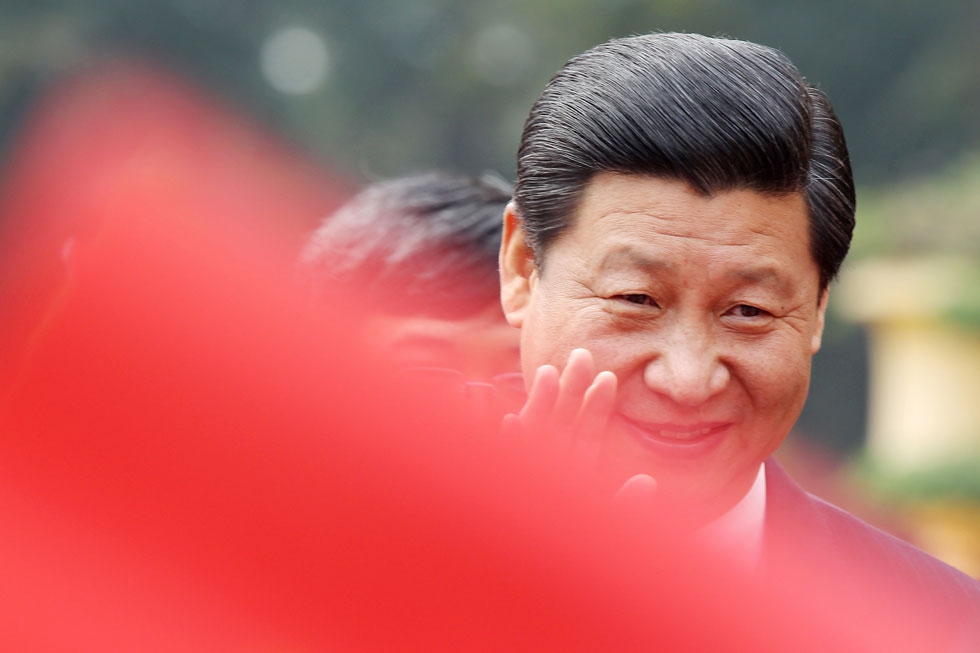

Xi Jinping and U.S.-China Relations in the Shadow of the Arab Spring

There are many things worth keeping in mind as Chinese leader-in-waiting Xi Jinping heads to Washington to meet with President Obama — including the simple fact that Chinese and American views of international issues often diverge sharply. There is never uniformity in either country on any topic, of course, but even taking into account considerable variations of opinion within each nation, the contrasts between the way some diplomatic topics are thought about on opposite sides of the Pacific can be striking. And these different worldviews can complicate meetings between leaders. At the present moment, for example, as Washington is frustrated by Beijing’s efforts to block U.N. actions in Syria, different views of the Arab Spring loom large.

To put the current divergence between U.S. and Chinese views of Syria into perspective, it is worth looking back to the Libyan crisis of last year, which reached a crescendo in September, when I happened to be in Shanghai for a conference. Just how wide the divide between Chinese and American views of the situation could be came home to me during a ride across Shanghai with a taxi driver who had strong opinions about everything — including Qaddafi.

After I got into his cab, I asked, as I often do when chatting with people in China in various setting, what he thought about the current situation in his country. This triggered a spirited lecture on the damage that rampant corruption was having on China’s laobaixing (a term that literally means “the hundred surnames” and is a widely used term for ordinary working people).

After talking about various other things, I brought up Libya. This was a natural enough thing to do, since the rebel take-over of Tripoli was the big international news story of that week. And the Chinese press was covering it pretty closely, a break from the media’s treatment of the earlier risings in Tunisian and Egyptian. Beijing had tried to suppress news of those events as long as possible, fearing that large-scale gathering to denounce corruption and authoritarian rule might give the Chinese laobaixing dangerous ideas.

“It looks like Qaddafi’s done for,” I said. “How do you feel about that?”

“Well, he’s a pretty bad man,” the cabbie answered, “but I don’t think it’ll be good if he’s overthrown. At least, it won’t be a good thing for Libya’s laobaixing. Libya is soon going to end up just like Iraq, and like with Iraq, all the Western powers really care about is the oil. Do you think the Iraqis are better off than they were in 2001? I don’t. How about the people of Somalia and Afghanistan? Are they doing well? No. There’s been no stability in those places, there’s been nothing but chaos since you Americans stormed in.”

These statements didn’t really surprise me, since they fit in with things I had come across in the Chinese press and on some Chinese websites, but they would certainly have had shock value to anyone whose vision of the situation had been shaped only be American coverage of the events.

The tendency in the United States had been to place the Libyan struggle in a lineage that went back to Tunisia and Tahrir, not to Baghdad and Somalia. And when the fight against Gaddafi was presented as a struggle between two abstractions, it was between “freedom” and “tyranny,” not “stability” and “chaos,” a pair of terms that crop up constantly in official Chinese discussions of many subjects.

The taxi driver, I should stress, was no knee-jerk supporter of all government positions. For example, he told me during the ride that he had been no fan of the 2010 Shanghai Expo, a lavish event that received nothing but praise in the official media. It had been, he said, just a giant waste of money.

His vision of Arab Spring and of China’s place within the international order, however, fit in neatly with positions staked out in the Chinese press. More specifically, in the Global Times, an official mouthpiece of the Party that is more tapped into international affairs than most other government organs (hence the name), but also more fiercely nationalistic.

The framing of an August 2011 Global Times poll on Libya was telling. It had not asked readers to speculate on the chances that democracy would come to Libya if Qaddafi fell, or weigh in on whether the international community was doing enough to topple him — two topics being debated at the time by talking heads on CNN and Fox News alike. Instead, it asked whether readers thought Libya would end up more “stable” if Qaddafi was deposed. More than four out of five respondents said “no,” just as my taxi driver would have if he’d been asked.

When the poll was taken, the American debate on Libya tended to revolve around whether Obama had been too cautious in his backing of the rebels. But one comment on the Global Times site, which was just an unusually direct expression of a fairly widely held notion, asserted that the insurrection in Libya was just the latest example of “running dogs of the Americans” doing “what the boss” told them to do.

A Global Times story I read while in China also veered off sharply from the standard American line. The European powers, it said, should not imagine that Qaddafi’s fall would be a panacea. The sovereign debt crisis should be their focus, the editorial insisted, not who ruled a North African country. Instead of stirring up trouble abroad, European leaders should concentrate on getting their own houses in order, with the London riots brought into the picture as Exhibit A.

Americans often expect most Chinese people to see the world roughly the way most people in this country see it, but this often isn’t the case. One reason is each country’s national mythology colors views of the international arena. American ideas about Tibet, for instance, are shaped fact the way struggles for religious freedom figure in our patriotic tales.

In China’s case, ideas about struggles to combat imperialism play a comparably central part in the national imagination. The so-called “century of humiliation,” which began with the Opium War in 1839 and ended with the Japanese occupation during World War II, get enormous play in patriotic education drives. The Communist Party has made a fetish of detailing in great but selective detail each painful episode in that period, such as the invasion by a consortium of foreign powers that took place in the wake of 1900’s Boxer Uprising. This approach to the past lays the groundwork for harsh criticism of any contemporary international situation that can be construed as a case of strong countries interfering with or ganging up against a developing one. Paired with this, in instances such as Arab Spring, is Beijing’s obsessive concern with stability at all costs, which fits in with the argument it makes continually through the official media that China’s economic boom has been the result of stable conditions.

None of this justifies actions such as the Chinese government’s effort to block U.N. moves to stem repression in Syria. Knowing the context, though, should leave us less surprised when Beijing behaves in a way that frustrates Washington in cases such as this. Where many Americans (myself included) see a valiant fight to topple a tyrant, China’s leaders sometimes see (and many ordinary Chinese are encouraged to see) a battle between trouble-makers and a man trying to keep his country stable.

There are many ironies to this situation. For example, the notion that “stability” should be prized at all costs was the excuse Westerners invoked in 1925 to defend a British-run police force in Shanghai firing into a crowd, which had gathered to call for an end to Japanese mistreatment of Chinese workers and for parts of the city controlled by foreigners to be given back to China.

Two decades after that, the Nationalist Party used similar rhetoric to defend using force again protesters. The demonstrations that time were by marchers who insisted that China was being dangerously misgoverned by a corrupt authoritarian figure whose only concern was maintaining his position in power and was being propped up by the United States.

Who was this Chinese figure being charged with misdeeds then so similar to those levied at Hosni Mubarak last year?

Chiang Kai-shek — the archenemy of the Communist Party that Xi Jinping will soon lead.