Novelist Min Jin Lee on the 'Eternal Foreignness' of Being Asian American

(Tracy Hunter/Flickr)

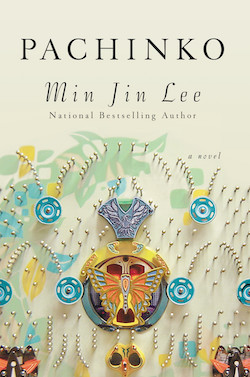

Novelist Min Jin Lee has made a career of telling the stories of people largely neglected by literature and popular culture. Her debut novel, Free Food for Millionaires, which follows the struggles of a young Korean-American woman striking out on her own in Manhattan, became a New York Times bestseller and was named a top 10 book of 2007 by NPR’s Fresh Air, USA Today, and The Times of London. Her sophomore effort Panchinko is a large, gorgeous book centered around a little-known group — the ethnically Korean population living in Japan. Lee traces the lives of four generations of a Korean-Japanese family, from absolute poverty to immense wealth in the era spanning Japan’s occupation of Korea to the late 1980s.

Every May for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Asia Blog interviews noteworthy Asian Americans from a diverse set of backgrounds. View the complete Q&A archive

Asia Blog recently chatted with Lee about the “eternal foreignness” of being Asian American, the dangerous lure of external validation, and living as a foreigner in Japan.

Part of the research for Pachinko involved interviewing Korean-Japanese people when you lived in Japan from 2007 to 2011. Who were some of the most memorable people that you met?

I met an ethnically Korean gentleman who rescued bar hostesses and sex workers in [Tokyo’s red-light district], Kabukichō. His father was a pimp and his mother was a prostitute, and they were not married. He grew up to become an activist helping women who had fallen into sex work. In Japan, it's really difficult for sex workers to be protected and then to get out because of the organized crime aspect and because of alcoholism or bad family situations.

He was very matter-of-fact about his situation and what he wanted to do to create change in Japan. That was a really cool way to deal with the fact that he was part of an oppressed minority. He saw himself as somebody who was kind of heroic. He was actually trying to help Japan.

What drew you to this subject?

Pachinko is an essential metaphor. I'm trying to argue that in all gambling, the house always wins and it's rigged. What I really noticed about this community is that they were in a situation created by history that was almost unwinnable. They were treated badly by history as well as by the nation in which they were living.

That said, when I visited the ethnic Koreans in Japan and spent an enormous amount of time with them, I learned that their attitude is, "I'm just going to do what I need to do. I'm going to survive because I can't count on the people who are in charge." They felt betrayed not just by the Japanese government, but by both North Korea and South Korea and by their own leaders in Japan.

They saw me as what I am, which is a progressive, liberal bleeding heart person and they were like, “Min Jin, you're getting way too upset about this; you just have to keep doing what you're doing.” I had to throw away my initial manuscript and start again because they did not see themselves as victims, but as very hardy and very resilient. This novel became about resilience, not just about oppression.

How has Pachinko been received in Japan and Korea?

I've been told several times that the English edition of the book is sold out in bookstores in Japan and Korea. It's interesting to see the English edition take over Asia. I can't tell you how surprised I am by it. I didn't think that people would care. I just thought this was my bizarro passion project. I started this book well before Free Food for Millionaires. I spent most of my life working on this book.

Have you heard directly from any readers in Japan and Korea?

The most gratifying letters I get are from people who say that they felt very recognized. They’re usually very emotional letters. An ethnically Korean person in Japan will tell me, "I don't know how you got access to all these people, but this is just like what happened to me or to my uncle or to my cousin."

.jpg)

Min Jin Lee (Elena Seibert)

It's so incredibly gratifying because I was very worried about getting all this stuff wrong. I did feel this real sense of historical responsibility because I knew that there wasn't a single novel written originally in English about this subject matter. I thought that this would be an academic press kind of book, that it would be recognized as something that we needed but wasn’t necessarily popular.

When you look at the U.S. book market, the percentage of translated literature is very small, but some Korean writers like Han Kang have recently found commercial success. How do you see this development?

I've been watching this issue for a long time because I read a lot of translated literature. Personally, I think it's really important to learn about other cultures besides those that have a dominant English-speaking body of media and literature. But in terms of its development, translated literature is still such a tiny percentage. The only way it's ever going to get better is if we have a critical mass of different books and not just one kind of book that gets translated.

Han Kang's book wasn't very well received in South Korea. The Vegetarian had almost no traction there when it was published. It's actually an old book; it didn't come out recently. Later on, it was translated by Deborah Smith from England and then it got the Man Booker International Prize. That is an interesting thing about Asia. When do we consider our own work important before we have a Western imprimatur and a kind of prestige associated with it? That's something we all have to really consider.

If something is really good we should talk about it and we should share it because it will only increase a greater understanding of the way we see ourselves and each other. That's the thing that I really recognize when I travel to universities — just how many kids of color are not recognized in media and literature. One of the primary things I work on is addressing the invisibility of Asians and the invisibility of Asian American art. Because art is our mirror.

You have stated that you wrote your first novel, Free Food for Millionaires, partly because of the dearth of complex Asian American characters. Has this situation improved since the book was published in 2007?

I want to say yes, but in so many ways, the invisibility of Asian Americans and also the eternal foreignness of it is perplexing. I am a parent of a college student and I am constantly addressing college kids. I'm so sad because they have the same issues that I had three decades ago. In some ways, Asian American kids get lumped in with the international students and it causes a weird separation.

The whole political angle of identity is something that people are made to feel ashamed of. They're made to feel we're post-racial, but we're quite there yet. A lot of kids that I talk to have never, ever known anything about Asian American literature or even Asian American history. And there is a rich American history in this country. The absence of history, the absence of a context, is making young Asian Americans really confused because there's a huge silence about this stuff. And parents often don't want to talk about it because it scares them. Or because they think it's distracting to their pragmatic goals.

One of the characters in Pachinko breaks up with his college girlfriend after he realizes she was only dating him because he was Korean-Japanese. Are you concerned that in the U.S. today Asian Americans are still being fetishized in that way?

Absolutely. Asians and Asian Americans and people of color are fetishized. There is also a very distinct experience for Asian American women as opposed to Asian American men. The way Asian American men are treated in this country by the media is simply appalling. If you are an oppressed, minority male there is a constant emasculation that's occurring. Every single male who is in that system has to ask himself, "How will I be a man?"

In Pachinko, Mozasu decides, “I'm going to become a man by making a lot of money because obviously I'm not very bright and I'm not good at school.” Noah decides, “I'm going to becoming a man by becoming such a respectable, exceptional Korean that they'll respect me.” And Park Chang Ho decides, “I'm going to become in this world and in this time in history by becoming a patriot.”

Those experiences reflect the way gender and race intersect to create a sense of identity as how the majority culture sees you and how you see yourself as a person of color. You can’t control the majority culture, but it's very important that you have a sense of integrity about how the world treats you and how you want to be seen, not as a reaction but as an active participant in your own life.

Is that quest to become a respectable man by seeking external validation ultimately elusive?

External validation will always destroy you. It's never enough, there's always a need for more. If you're living in New York, you know there's always somebody more attractive, more wealthy, with a better pedigree, more whatever than you. You could do this forever. This treadmill is just ruthless. At some point, you have to make peace with how you see yourself. And then the external validation, if it comes, great. If it doesn't come, I'm sure it's heartbreaking, however, you still have to manage to live with yourself.

Another character in Pachinko notes in 1989 that “nothing would ever change” in Japan, pointing to that society’s unwillingness to assimilate the Koreans born there. Has Japanese society become more tolerant?

I think Japan's approach towards non-Japanese will never change. The Japanese are a terrific people. That said, there is something about Japanese culture that takes great ownership and pride in ethnic and blood heritage. You could become a Japanese citizen today after being there for four or five generations but no one will ever think of you as Japanese. In order to be considered Japanese, you have to be fully by blood Japanese. I've interviewed hundreds of people about this issue and every Japanese person has said that a biracial Japanese person is not Japanese. I think that's fine. I think that's just the way a culture is.

I don't think South Koreans are necessarily different. I don't think Koreans approach foreigners in a better way. I've been very critical in this book as well as in public about the way South Korea treats the Korean-Japanese people. If you look at the history of how the Korean-Japanese are treated in South Korea, it's appalling.

It's not like America is perfect, but America has a very long and rich history of having to integrate different kinds of people. I'm a naturalized American citizen and in certain parts of America, I'm seen clearly as an American and people wouldn't deny this. But that doesn't happen actually in many other parts of the world. They don't see other people as being of that nation because of their bloodline.

Throughout Pachinko, the Korean-Japanese are treated like second class citizens. Today, with the so-called Korean wave, or hallyu, Korean films, music, and television are widely consumed in Japan. Would you characterize this as something of a “revenge” for South Korea?

Selling soft culture is a very explicit intention of the South Korean government in the same way South Korea wanted to join the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Hallyu is a very cool phenomenon just as Japan soft culture is probably the most amazing thing about Japan right now. We really accept sushi or Pokémon or the manga culture, all those things from Japan. The fact that we have emojis — those are Japanese creations.

I do think it's problematic to think Korean soap operas or soap stars are acceptable, while one’s Korean-Japanese neighbor is still considered a criminal. That's not okay. What I noticed when living in Japan is that people who are obsessed with hallyu, who are obsessed with South Korean TV or food, still felt very comfortable thinking that all the crime in Japan came from the Koreans and the Chinese. It's quite possible to have this bizarre binary in your head. That may not be a Japanese problem. It may just be a human problem where we are always having to make these distinctions of what's good and what's bad.