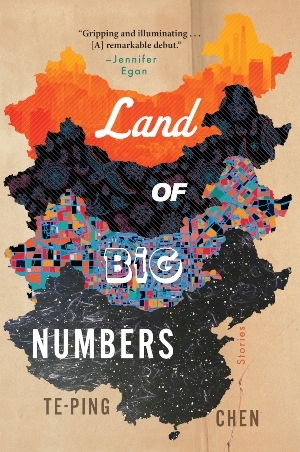

'Land of Big Numbers' Author Te-Ping Chen on Writing Her Way Through the Dark

Commuters crowd a subway station at rush hour in Beijing, China. (Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

A college student finds her voice with online political activism — but at what cost to her safety? A rural pensioner tries to impress a local official by building an airplane in his yard. A young government employee, envious of his wealthy friend, becomes enmeshed in the stock market. A group of commuters becomes stuck in a subway station for months — only to find that they never want to leave.

These are among the characters created by Te-Ping Chen, the author of The Land of Big Numbers, her debut collection of short stories. Chen, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal who was long based in Beijing and Hong Kong, presents a nuanced, intimate portrait of ordinary Chinese lives — a population struggling to navigate the dizzying changes in their country. Her stories, writes Shiner author Amy Jo Burns, possess "the great quixotic feel of being ancient and modern all at once."

Chen is now based in Philadelphia, where she writes about work and work culture for The Journal. She recently spoke with Asia Blog about fiction, journalism, and what her stories say about modern China. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You’ve been a journalist for a while, and also now write fiction. What both have in common is that they’re forms of storytelling. What does fiction allow you to do that nonfiction doesn't?

In large part, journalism is the delivery of meaning through facts, and fiction is the delivery of meaning through experience. When I was working as a correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in Beijing, so much of what we wrote was dictated by what was in the news. We always thought of stories through the lens of what was timely. As a journalist, I believe strongly in the ability of facts to move audiences. But as a reader and a fiction writer, I also believe powerfully in the ability of fiction — of experiences — to change people's minds. That’s the reason travel can be so transformative, right? It’s one thing to read something, but it's another to be more deeply embedded in a society.

As a reporter who spent a lot of time trying to capture China and think about what it means to tell Chinese stories, I felt that I wanted that wider canvas. Headlines, out of necessity, can be reductive. And as a reader, I always felt like I craved more. That’s something that animated a lot of the writing in The Land of Big Numbers.

What inspired you to write fiction?

It was something that I had always done, off and on, over the years. Ever since I was young, I’ve written poetry and fiction. And in the period after I first moved first to Hong Kong and then Beijing to work with The Wall Street Journal, I’d find myself being drawn back into the world of fiction — almost compulsively. China is just such a propulsive place on every level, particularly sensory, and I always had a feeling that there were so many stories that demanded telling. In some ways, journalism is the architecture of the house. But it doesn’t always take you inside. In writing fiction, my hope was to take readers inside the house, too.

How does your process of writing fiction differ from writing a 1,200 word article?

Oh, it’s so different. With journalism, you're writing towards an end, with a feeling that you need to have all the answers. And for me, at least, fiction is a process that feels much more unbound. You're almost writing your way through the dark. As you start to write, it’s like having a flashlight, and as you move around the room, and you get acquainted with the space and bit by bit, this world unfolds itself.

For Land of Big Numbers, I would write first thing in the morning. There was something about the freshness of the morning that gave me the ability to step in and out of worlds. And the writing, so often, would surprise me in ways that my journalistic writing did not.

One of the themes of Land of Big Numbers is dislocation. Your characters are often people who are thousands of miles from home, or who interact with people very different from themselves. Do you see China’s changes over the last 40 years as having brought the country’s people together? Or has it made them lonelier and more isolated?

I think both. At times, China can feel like a deeply lonely place, even when you're surrounded by so many people. It’s easy to feel that sense of dislocation, like Xiaolei (from “Shanghai Murmur”), a character who works in a flower shop, or Zhu Feng, the protagonist of the title story, who’s a young government bureaucrat speculating in the stock market. There’s loneliness in a personal sense — but there's also the broader sense of being left behind by the economy and by friends that have surged ahead and become more prosperous.

But there are other points in the book — for example, the story set in Beijing’s hutong (“New Fruit”) which is told through a choral “we.” The story is not about a single person — it's about a community. A lot of what you see too, in China, are people embedded in these structures, like the title character in “Lulu,” whose family structure made her more aware of her differences. But as with anything in China, it's hard to generalize.

Te-Ping Chen (Lucas Foglia)

In “Gubeikou Station,” you write about a group of people who get trapped in a subway station for months. Over time, a lot of them become so accustomed to it that they even begin to like it, and become reluctant to leave. Is this story a metaphor for China — or for human nature more broadly?

I was writing it in China, of course, and so I think the themes of the story absolutely sprung from that experience — in particular how readily adaptive this group of commuters are, and the degree to which their sense of self gets shaped by state media. I wanted to explore the idea of how easy it is to grow comfortable with a lack of autonomy.

I guess you could argue that it was a particular “China” thing — but I think it’s a pretty fundamentally human one, too. Like this question of: To what degree do we attempt to challenge the circumstances around us? To what extent do we accommodate ourselves? There's something extraordinary about the human spirit and how resilient we can be, and how we have the ability to adapt and thrive no matter the circumstance. The idea behind “Gubeikou Station” is how terrifying, at the same time, these very human traits can be. But I think these traits exist, no matter the social context. It's something that's latent within all of us.