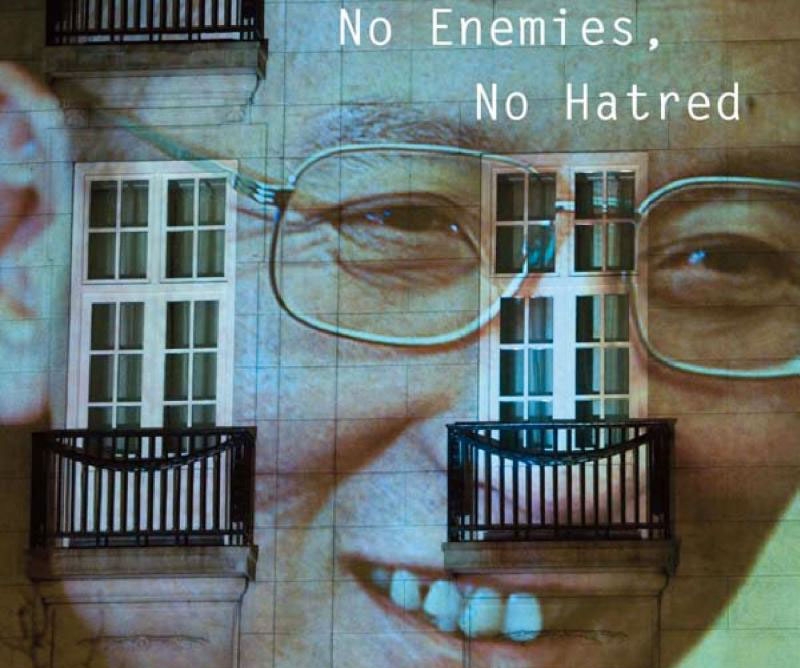

Interview: Perry Link, on the New Book From Chinese Dissident Liu Xiaobo [UPDATED]

UPDATE: Scroll to the end to see Perry Link read from and discuss the book he edited, No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems by Liu Xiaobo.

***

What may become an iconic slogan of China’s brief Jasmine Spring, No Enemies, No Hatred, is the title of a new collection of translated poems and essays by 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, the primary author of the Charter 08 manifesto, a pro-democracy petition, signed by thousands of political dissidents, that eventually landed Liu in jail. Before he received his 11-year sentence on Dec. 23, 2009, Liu uttered, “I have no enemies, and no hatred,” in reference to his advocacy of peaceful-resistance.

Word of Charter 08 and of Liu’s imprisonment quickly traveled west. In 2010, Liu received the Nobel Peace Prize though he was barred from traveling to Oslo to receive the award. His wife, Liu Xia, was also detained and placed under house arrest.

No Enemies, No Hatred introduces English-speaking audiences to Liu’s writings for the first time — a careful selection from the 17 books and hundreds of essays and poems he has penned. The book was edited by Perry Link, Chancellorial Chair for Innovation in Teaching Across Disciplines at the University of California, Riverside, and a contributor to The New York Review of Books, Tienchi Martin-Liao, a Chinese-born human rights advocate based in Washington, D.C., and Liu Xia.

Asia Society spoke with Link by email about the new book, which he also discussed in a panel last Thursday at Asia Society Northern California.

Can you tell us how how the pieces were selected for this book?

The essays and documents were selected by Tien-chi Martin-Liao consulting with Hu Ping (the editor of Beijing Spring) and others. The poems were selected by Xiaobo's wife Liu Xia.

How does Liu Xiaobo's Charter 08 differ from previous dissidents' treatises such as Wei Jingsheng's Fifth Modernization in 1978?

Charter 08 is far more panoramic than other such statements, including Wei's, because it comments not just on free expression, press, and assembly, on academic and religious freedom and on voting in elections, but also on law and constitutions; on school curricula; on tax policy; on environmental protection; on China's history; on truth-and-reconciliation; and more. It is also more sophisticated than earlier dissident statements. It is important to realize that many people — experts in many fields — cooperated to draft it. But all that said, what stood out from the Communist leaders' point of view, what clearly angered them and led them to repress the Charter — and what was, to answer your question, different from any previous dissident statement — was the proposal to end one-party rule.

I have heard that despite China's censorship of the internet, the "Great Firewall" is not as impenetrable as it is touted to be, and that many people there now know about Liu Xiaobo. Do you think that is the case? And if so, how much do you think Liu Xiaobo's writings resonate among the general populace in China?

Before the Nobel Prize, Liu had only a few thousand readers, maybe in the tens of thousands at most. The prize caused many more people to seek out his writings, so — and I'm just guessing here — people inside China who have read him now probably number in the millions or tens of millions. His readership is still far behind that of popular bloggers like Han Han, who have hundreds of millions. But your question in part is about "resonating," and here I think one has to say that ideas like those in Charter 08 resonate wherever they reach. The CCP's assiduous attempts to block the spread of Charter 08 are strong evidence that the authorities themselves know that these ideas have the potential of very, very broad appeal.

Perry Link signs a copy of 'No Enemies, No Hatred' last week

at an Asia Society Northern California event.

What do you think of the criticism some exiled pro-democracy activists launched against Liu Xiaobo — that he shouldn't have received the Nobel and that his views are too moderate? Are there factions within the pro-democracy movement?

Of course there are factions. Even something as large as a "faction" sometimes cannot hold together. But, look, here is a fundamental fact: In order to stand up to a mighty authoritarian regime, to tolerate harassment, prison, and forcible separation from home and family, a person needs to have extraordinary self-confidence and strength of will. Every Chinese dissident I know has these qualities. So how do such people interact with one another? Well —and this should be no surprise — by showing extraordinary self-confidence and strength of will. This leads to frictions, rivalries and factions. But intellectually, in their views of China, they are almost of one mind. There were endless quibbles in the drafting of Charter 08, but everyone, including Liu Xiaobo's critics, endorses the charter's main themes, both then and now.

Is China's pro-democracy movement making any progress?

Yes. Lots of it. To understand the question properly, one needs to see "democracy movement" as something much broader than just elite dissidents who are sophisticated about democratic theory. The important progress is coming as more and more ordinary people see themselves as having "rights" — rights to know things, to express themselves, to bring pressure of organized public opinion, and even, sometimes, to rebel. There is much more "rights awareness" at the popular level in China than there was 20 years ago, to say nothing of during the Mao era. The internet has played a crucial role in its spread.

The team that put together this new book includes Liu Xiaobo's wife, Liu Xia. How were you able to work with her while she was under house arrest? What pieces did she select for the book? And, if I may ask, how are she and Xiaobo coping?

Liu Xia chose the poems for the book before Liu Xiaobo was detained in 2008 and before she herself was put under house arrest, which happened right after the announcement of the Nobel Prize in October 2010. No one on the outside knows how well the two Lius have "coped" since then. Liu Xia was extremely tense and distraught in the winter of 2009-10 when Xiaobo was sentenced and sent away to Jinzhou Prison.

China Human Rights Defenders, a group that is close to Liu, reported in late 2010 that Liu was being held with five other inmates (although veterans of Chinese prisons suspect that these five, inmates or not, are there to report on him) and being provided with low-quality prison food. His cell mates were allowed to pay the prison to get specially prepared, better food, but he was denied this option. He received two hours each day to go outdoors. He could read books, but only if they are books published and sold in China. There was a television set in his cell, and the prison authorities controlled which programs he could watch. There are rumors that Liu Xia has been able to see Liu Xiaobo during the past year, but the stories are unconfirmed.

What has been the most significant development, if any, since Liu Xiaobo was detained and then awarded the Nobel Peace Prize? What are the chances that he might be released early or perhaps exiled from China?

He has made it clear that he will not accept exile. I have no evidence that the authorities have offered him exile, but I believe it is likely that they have done so, and likely that he said no. Whether he will be released before his term ends in 2020 depends on whether there are major shifts in the tectonic plates of Chinese politics between now and then. This could happen, but not because of anything Liu Xiaobo can say or do while in prison.