Interview: Deborah Baker's 'Convert' Presents a Life of Exile and Extremism

Deborah Baker has written well-received biographies of offbeat characters. The titles include Making a Farm: The Life of Robert Bly, In Extremis: The Life of Laura Riding, which was short-listed for a Pulitzer Prize in Biography in 1994, and A Blue Hand: The Beats in India, which became the centerpiece of a day-long Asia Society symposium in 2008.

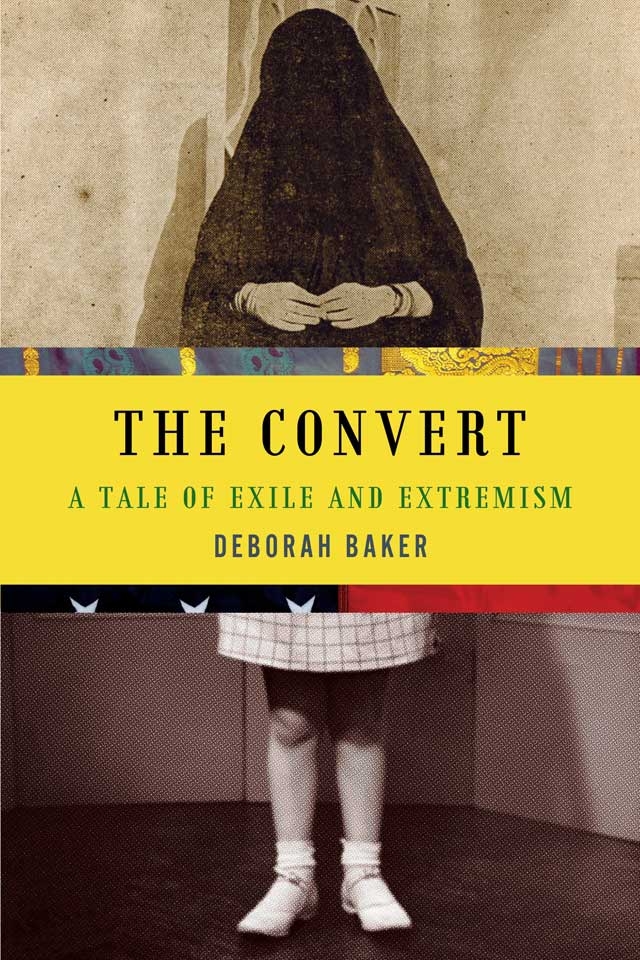

Her latest book, The Convert: A Tale of Exile and Extremism, relates the life of Maryam Jameelah, a New York Jewish convert to Islam who emigrated to Pakistan in 1962 and became a spokeswoman for Islamic fundamentalism.

Baker spoke about the book at an Asia Society India Centre event in Mumbai late last month, where she was joined by renowned historian Shahid Amin. Immediately after that appearance, Asia Blog interviewed Baker via email about the inspiration behind her latest book, the choice of Jameelah as the subject and life in Lahore.

The story of how Margaret Marcus of Larchmont became Maryam Jameelah of Lahore is extraordinary. How did you decide to write about her?

The decision came some months after I stumbled upon her archive at the New York Public Library. The more I read her letters and understood the story they had to tell, the more it became clear that this was a book I was fated to write.

Islam remains one of the least understood religions in the West. Have relations changed between Islam and the West from the time when Jameelah embraced Islam (in the 1950s) to the present? If so, how have they changed?

"Islam" and the "West" are not walking and talking realities, capable of having a prone-to-misunderstanding sort of relationship. The point of the book is to use the works of Maryam Jameelah and Mawlana Mawdudi to trace how recent the history of these two constructs really is and, at the same time, tell the story of two families' efforts to overcome the misunderstandings that result when we take the idea of "the West" and "Islam" or "believer" and "infidel" too literally.

What were your impressions of Lahore? How long were you there?

I was in Lahore for two weeks in December 2008. It was during the State of Emergency under Musharraf. I arrived two months after Benazir's return from exile, and left just before her assassination. The city was in the midst of demonstrations and lawyers protests against the house arrest of the chief justice, yet there was a sense of excitement about the promise of the coming elections. The demonstrations filled people with energy and courage, though many had been beaten and imprisoned. I got some sense of the beauty of Lahore, particularly the small quiet shrines to Sufi saints where people came to say prayers, or men to hang out and talk.

I've since learned that many of these places have been shuttered out of fears of suicide bombers. The people I stayed with, members of the television and print media, are now living in exile because of death threats over stands they have taken and reportage they have published. So I imagine that my brief acquaintance with the city and the impressions that came with it, are sadly dated.

Maryam was apparently diagnosed with schizophrenia. In your opinion, did that affect her narrative of her life in Pakistan?

Maryam was diagnosed in 1950s when lots of people were being diagnosed as schizophrenics. Many were also being institutionalized for being homosexuals, or communists or just unhappy housewives. I am not at all sure she would be so diagnosed today. Such labels were often used to marginalize people who didn't conform entirely to the narrow identities allotted them during that postwar period. Maryam was a strong-minded woman, unwilling to make the kinds of compromises and accommodations that most people do without thinking in order to better get along in life, whether in 1950s America, 1960s Pakistan, or now.

The framework of militant political Islam laid out by Moulana Abul Ala Mawdudi offered a limited role of women. What attracted Jameelah to it, and why did she stay?

She found a place for herself in Lahore, a husband and family as well as an outlet for her writing. In times of upheaval, whether it is post-Partition Pakistan or postwar America, the desire for security and consensus on how the conduct of life should be legislated, can be overwhelming. It is often women who find their allotted roles most narrowly defined in such periods, but Maryam managed to both observe purdah and achieve professional renown.