In China, a Long Tradition of Dodging the Sun [Photos]

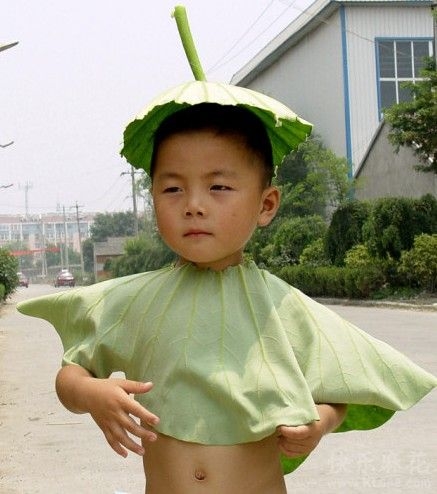

WSJ.com's Scene Asia blog recently posted a series of photos of women in China wearing masks while bathing in the ocean, an apparent effort to preserve their fair complexion. Many similarly ingenious methods of avoiding the sun exist in China (and other parts of Asia), as you can see in the photos above. But how did this preference for light skin originate?

Fair Skin Through the Ages

Chinese empress Zhao Feiyan

Pale skin has historically been prized as beautiful in China, and the concept is widespread in other Asian countries, such as India, as well. An early Chinese woodcut scroll, New Chants of a Hundred Beauties (百美新詠圖傳), first published in 1792, mentions one of the fabled beauties of China, empress Zhao Feiyan (right), as having "slender waists and snow-white skin" (细腰雪肤), attributes that became among the "Ten Commandments of Classical Beauty" in ancient China. That image of beauty has endured over time.

Zhang Lijia, a Chinese writer and journalist who came of age in early post-Mao China, recalls the social inferiority of having a darker skin in her autobiography "Socialism is Great!": A Worker's Memoir of the New China. "With darker skin and coarse hands, they had clearly been 'repairing the earth' — their scornful term for tilling the land," writes Zhang about some of her factory co-workers. Later in the book, she recalls, "In his better moods, Father shouted jokes with little regard for taste or sensitivity. 'You're not our natural daughter, you know,' he used to tell me when I was little. 'We picked you up from a coal dump. That's why you're so dark.' Most Chinese consider dark skin ugly. His joke haunted me for years."

Making Oneself Light

While the veneration of thinness and demureness as standards of beauty historically shifted in China, fair skin has consistently been prized and pursued. Once upon a time, according to a chemical pathology professor at Chinese University, people would actually crush pearls into powder that they would then swallow in hopes of attaining whiter skin.

In traditional Chinese medicine, meanwhile, there are recommendations for eating peas for lighter, more lustrous skin in the medical compendium Bencao Gangmu (本草纲目); for an herbal concoction for lighter skin from a Ming dynasty medical reference, Introduction to Medicine (医药入门); and for a Three Whites Soup (三白汤), containing white peony root, white atractylodes, white tuckahoe and licorice.

Skin whitening creams and powders to lighten skin have also been popular in Asia for a long time. Susan Brownell, author and professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, cites the calamitous wars of the mid-20th century as one explanation for their appeal: "Historically, Japan and Vietnam and other parts of Asia that have been militarily occupied by U.S. and European troops, you can definitely trace an influence. ... Particularly where you've got a lot of prostitution going on, where you've got local women trying to make a living by being prostitutes or marrying American and European soldiers, that also tends to influence beauty practices."

A 1948 advertisement for Shiseido face powder makeup

reads (top left): "Produces fresh colors/ Attractive beauty!"

(MIT's Visualizing Cultures project)

Brownell continues, "I would almost think that today, beauty ideals across East Asia are fairly uniform just because there's so much mutual influence, in terms of pop stars and also the cosmetics industry. Of course, the Japanese cosmetic companies were the first ones to move into China in a big way, like Shiseido."

A kind of face powder, Three Phoenix Begonia Powder, very popular in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia in the 1980s, was a block of calcium carbonate and talcum women applied on their faces to look fairer. These days, the product is favored by jewellers and watch restorers to remove rust and tarnish, as it has abrasive properties.

The promotion of fair skin as being socially superior has resulted in pushback from women's groups. A television advertisement in India in 2003 for skin whitening cream, Fair and Lovely by Unilever, had to be pulled when the ad suggested that a darker complexion prevented girls from getting better jobs or getting married.

In addition, many of these creams have been found to contain unacceptable levels of mercury, some containing up to 131,000 times the amount permitted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and some users have suffered mercury poisoning as a result of using them.

Fair's Fair — and Here to Stay

Despite the touted health risks of these skin whitening products, there seems to be little indication that demand for a lighter skin will ease in many parts of Asia, as the skin whitening industry is projected to exceed the $2 billion mark in 2012, given the fast-growing markets of China and India.

Could there be a sudden turnabout in perceptions of beauty, in which Chinese people would start to prize tan skin instead? Brownell doesn't think so. "We did a reversal in the U.S. probably around the 1930s, where before that women wanted to be white," she says. "People argued what caused that was perhaps this move away from an agricultural society. Suddenly most people were this middle-class working indoors and they were white, and people showed off their high status by getting tanned, which means they have the leisure to get outside the office."

Brownell adds, "By that logic, you might expect the same thing to pertain to Asia, but I'm not so sure, because you have to factor in their strong distaste for manual labor. In China, you've got a huge number of the population that just one generation ago were still farmers. As long as they're still trying to leave that behind, as long as it's a little stigmatized, I imagine that's going to act against a deep tan becoming the mode."