'Chemistry' Writer Weike Wang on Redefining the Coming of Age Novel

Author Weike Wang receives the 2018 PEN/Hemingway Award for her novel 'Chemistry' at the PEN/Hemingway Award Ceremony at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum on April 8, 2018 in Boston, Massachusetts. (Paul Marotta/Getty Images)

Paul Marotta/Getty Images

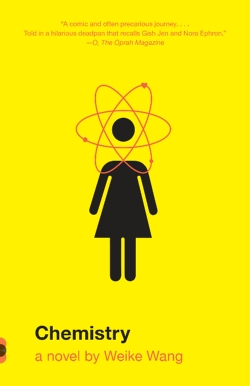

In Weike Wang's debut novel Chemistry, the unnamed narrator, a graduate student in chemistry, finds herself struggling to maintain interest in her subject and, more concerningly, deal with a marriage proposal from her boyfriend. This predicament sends the student on a "comic and precarious journey" of self-discovery, free from the constraints of family, love, and duty.

Wang didn't have to go far for inspiration. Born in China and raised in the United States, Wang earned degrees in chemistry and public health from Harvard University while simultaneously pursuing a Master's of Fine Arts at Boston University, where she published fiction in numerous literary magazines. Chemistry was honored with a PEN/Hemingway Award for "elliptical prose" in April and was named a notable book of 2017 by the Washington Post.

Asia Blog recently caught up with Wang to talk about her writing process, the universality of "Asian American" themes, and whether her novel is or is not a coming of age story. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Your narrator faces a lot of pressure stereotypical to Asian Americans: Dealing with extreme parental pressure to succeed in a practical field, such as chemistry. When you were growing up, did you encounter this story much in American fiction?

I actually don't think [my novel's] story is unique to Asians or Asian Americans. It's a coming-of-age story and something of a redemption story, which are some of the oldest themes in literature.

When I was growing up I was interested in stories that weren't defined by their race. For a lot of Asian American literature, being Asian was a defining factor. I wanted to tell a story in which my character being Asian was a factor, but not necessarily at the forefront. I wanted it to be more subtle.

The New York Times referred to Chemistry as an "anti-coming of age story." Do you agree?

I still think it’s a coming of age novel. The way that “anti-coming of age” is used here is that the novel ends in the middle of [the narrator's] development. She’s on the upswing as far as potential for change, but you don’t see the victory dance — or the resolution of “ah, they’re together or not.”

I didn't want to show drastic change because drastic change takes so much time. By the end, a lot has happened, and yet not a lot has happened. She’s learned something, but she’s got a lot more to learn. She’s just started.

You’re Asian American and have written a book whose central character is Asian American. Are you concerned that you’ll be stereotyped as an Asian American writer rather than just a writer?

That's something I think a lot about and struggle with. Most of Ernest Hemingway's characters are white. But nobody would have asked him, "Don't you think you can write characters of other races?"

When I started writing 10 or 15 years ago I made a conscious decision not to pigeonhole my characters by identifying them by name or race. But in the process of writing my novel, I asked myself: "Who am I waiting for to write a great Asian American character?" Some of the best prose writers in America probably wouldn't do it. So I felt a certain responsibility to have an Asian American character. She could still have other characterstics, of course, like owning a dog, or having certain issues.

But it's something I do worry about. When I develop characters, I really put in my all. I write for myself but I also write for readers my characters may represent.

How did your decision to pursue an MFA alongside your degrees in chemistry and public health play with your family?

I was pretty honest with them from the beginning. I never approached my parents without a plan. I don't think that's necessarily Asian, either — everybody's parents want them to have a plan when asking for money. So I went in with the plan to do my MFA concurrently with my Ph.D.

I applied to the MFA and said that if I didn't get in, I didn't get in. My parents were supportive but, like anyone's parents, cautious: I was leaving something practical for something impractical. But as long as I could support myself and have medical and dental insurance, they were happy. Isn't that the dream of every parent? To have their child insured?

What did they think about Chemistry?

They haven't read it. Neither have my in-laws. Only a few of my friends have.

What advice would you give aspiring novelists?

Read a lot. Especially non-fiction. Understand that revision is a huge thing. I thought that once I'd written my book, I’d edit it once or twice and it’d be done. But the whole revision process is mind-boggling. A lot of the craft and nice transitions come from editing. That’s something I’ve learned: You might feel good about your story today, but you’ll feel even better tomorrow when you’ve cut out the fat. Or you might feel bad about it today, but you’ll feel better about it tomorrow when you’ve revised it.

Do you thoroughly map out your stories and characters before you begin a project? Or do you just start writing?

The latter: I figure it out as I go along. I'm not a good outliner. Writing characters is like raising a child, essentially. It takes awhile to get to know them.

A lot of my friends will write something from every angle 500 times. For me, I just start. One sentence turns into another and into another, and I delete and move things around. The problem is that this method is really inefficient.

You have to remember the entire novel in your head. You think, "Oh, I used that line. I used that structure. I can't use them again." But that's why you have an editor, and that's why you read it multiple times.

If I could find something else I loved to do, I'd do that. Writing is so painful.