Book Excerpt: 'Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific' by Robert D. Kaplan

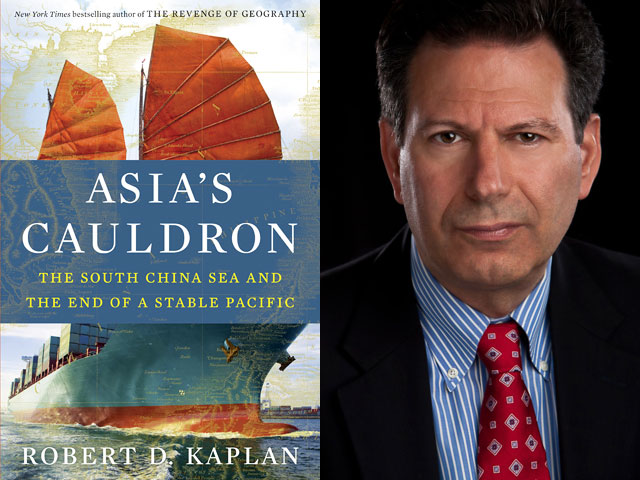

"Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific" by Robert D. Kaplan (Random House, 2014). (Author photo: Maryna Marston)

On Wednesday, November 12, Asia Society New York will present a panel discussion examining the ways in which the ongoing South China Sea dispute might be disentangled while avoiding disastrous conflict between its major players. (For those who can't attend in person, the panel will also be webcast live at AsiaSociety.org/Live at 6:30 pm New York time on the 12th.)

Among the distinguished scholars and analysts who will explore some of the questions surrounding the future of the South China Sea in the panel is Robert D. Kaplan, Foreign Correspondent for The Atlantic for nearly three decades and the author of 15 books on international affairs and travel. Foreign Policy named Kaplan one of its "Top 100 Global Thinkers" two years in a row, and he is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security in Washington, D.C.

Kaplan's latest book, published earlier this year by Random House, is Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific, a survey of the key international stakeholders involved in the South China Sea, the issues underlying the growing tensions in the region, and their implications for peace and security worldwide. An excerpt from Asia's Cauldron appears below.

CHAPTER VIII

THE STATE OF NATURE

I am situated by a frozen lake, with gray pagodas and upward-curved roofs in the distance visible through the Beijing smog. There is the sickly sweet smell of coal burning. I walk inside a traditional tea house, filled with porcelain, rice paper paintings, lime wood furniture, and a massive red Turkish carpet. In other words, I am in a world of elegant and traditional aesthetics: a world with which sophisticated global elites are comfortable. This is China as seen through the pages of an expensive coffee table book. My companions are members of an internationally renowned foreign policy institute in Beijing. The atmosphere is convivial. We talk to each other across a geopolitical divide, but actually less so across a cultural one: since we are all similarly educated, all frequently visit each other's countries, and all consequently seek out compromise. Everyone here is equally worried about the stability of the North Korean regime and about the direction of both the American and Chinese economies. There is a discussion about how we can get our two countries' navies to better cooperate. The get-together reminds me of how richly developed United-States-China relations are. Millions of American and Chinese have visited each other's countries, tens of thousands of American businessmen pass through Beijing and Shanghai. Chinese political elites send their children to be educated at American universities. This is not the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, when I was a lonely American in Eastern European capitals. "Containment" is a word from a previous era, one that simply does not fit the American security approach to China, I tell myself.

But that evening I am somewhere else in the Chinese capital. Rather than in a realm of quite elegance, I am now in a loud and tacky new hotel under sharp and glaring lights. There is a lot of fake gold and plastic. I eat dinner with two members of a Communist Party foreign policy think tank. They are badly dressed and speak through an interpreter. They tell me that the Japanese national character has not changed since Pearl Harbor. They defend the nine-dashed line which asserts China's claim to virtually the entire South China Sea. They claim the right for China's navy to protect its sea lines of communication across the Indian Ocean to the Middle East. The Vietnamese are unreasonable, they tell me. They warm up to me only after a I provide a short disquisition about how much I am aware of the territorial violations inflicted upon China by the West and Japan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yes, here I could be back in Cold War Eastern Europe.

As different is the American relationship with China from the Cold War one with the Soviet Union, the fact remains that China and the United States are two great powers with competing interests in the Western Pacific, and while the experts one meets at Beijing's universities and institutes seem reassuringly flexible — members, as they are, of the global elite — they are not in power: and those that are in power are less flexible. Though, of course, the situation is far more complicated than that. For even within the ranks of China's navy, there are significant voices for moderation alongside tougher assessments.[1] Beijing is indeed rich in differences of opinion. However, throughout Beijing, one is inundated with the nostrum, while China only defends, the United States conquers. The South China Sea is the nub of the issue. Hardliners and soft liners alike in Beijing — deeply internalizing how China suffered at the hands of Western powers in the recent past — see the South China Sea as a domestic issue, as a blue water extension of China's territoriality. One night at a seminar I conducted for Chinese students, one shy, quivering young man blurted out:

"Why does the United States meet our harmony and benevolence with hegemony? U.S. hegemony will lead to chaos in the face of China's rise!"

This is vaguely similar to a Middle Kingdom mentality, in which China must defend itself against barbarians. Indeed, the South China Sea and its environs are China's near-abroad, where China's is harmoniously reasserting the status quo, having survived the assault upon it by Western powers. But because the United States has come here from half-a-world away in order to seek continued influence in the South China Sea, it is demonstrably hegemonic. Likewise in the Indian Ocean, where China has legitimate commercial and geopolitical interests, while America's interests, again, are merely hegemonic. It is the United States, so the reasoning in Beijing goes, "that attempts to keep Asia under its thumb and arrogantly throws its massive power projection capacity around." Because Washington is seen as the "agitator" of South China Sea disputes, it is the United States, not China, that needs to be "deterred."[2] After all, China dominated a tribute system based on Confucian values that defined international relations in East Asia for many centuries, and resulted in more harmony and less wars than the balance of power system in Europe. So the West and the United States have nothing to teach China in regards to keeping the peace.[3]

These are different world views informed by different geographical points of reference. They may have no ultimate resolution.

Thus, we are back to containment, the wrong word that unfortunately harbors a great truth: that because China is geographically fundamental to Asia, its military and economic power must be hedged against to preserve the independence of smaller states in Asia which are U. S. allies. And that, in plain English, is a form of containment. A confident, business-like official at the Foreign Ministry in Beijing understood completely the dilemma, when he half-warned me: "Don't let these small countries [Vietnam, the Philippines...] manipulate you." China understands power, and thus it understands the power of the United States. But it will not tolerate a coalition of smaller powers allied with the United States against it: that, given the Chinese historical experience of the past 200 years, is unacceptable. As for the nine-dashed line, as one university professor in Beijing told me: sophisticated people in government and in the foreign and defense policy institutes here recognize that there must be some compromise down the road, but they need a political strategy to sell such a compromise to a domestic audience, which harbors deep reservoirs of nationalism. In the meantime, the Chinese have doubled-down on the nine-dashed line: establishing a prefecture of 200 islets encompassing two million square kilometers of the South China Sea, with 45 legislators to govern it.

Notes

[1] Lyle Goldstein, "Chinese Naval Strategy in the South China Sea: An Abundance of Noise and Smoke, but Little Fire," Contemporary Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2011.

[2] Jonathan Holslag, "Seas of Troubles: China and the New Contest for the Western Pacific," Institute of Contemporary China Studies, Brussels, 2011.

[3] David C. Kang, East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute, Columbia University Press, New York, 2010, pp. 2, 4, 8, 10, and 11.

From the book Asia's Cauldron by Robert D. Kaplan. Copyright © 2014 by Robert D. Kaplan. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.