"Spellbinding"

— The New York Times

"Rapturously beautiful"

— The New York Review of Books

"A stellar lineup"

— The Wall Street Journal

"Superb"

— The New York Times

Watch: Preview of works featured in Kamakura

About Kamakura

The magnificent sculpture of the Kamakura period (1185–1333) has long been considered a high point in the history of Japanese art. Stylistic and technical innovations led to sculpture that displayed greater realism than ever before. Sculptors began signing their works, allowing us to trace the development of individual and workshop styles that influenced later generations for centuries. Religious developments—often combinations of traditional and new practices—brought devotees into closer proximity with the deities they worshipped.

The icons in this exhibition commanded the faith of passionate devotees, some of whom hoped to gain merit from the making of a Buddhist image, to ensure salvation in the afterlife, or to obtain tangible benefits in this life. Others aimed to achieve ultimate awakening through ritual unification with the deity represented by the icon. In their original contexts these powerful icons were “real presences,” brought to life by their naturalistic form, ritual activation, and sacred interior contents.

Craftsmen created these icons during a time of profound political and social disruption. For the first time in Japanese history, powerful warrior clans challenged the imperial court that had dominated the political and cultural landscape for centuries. In the civil war of the 1180s, the great Buddhist temples of the ancient capital in Nara burned to the ground. The devastation shocked the entire country, but rebuilding and repopulating the temples with new sculptures and paintings began almost immediately. Renewed contact with the Asian mainland, which flourished in the early Kamakura period, further invigorated arts and religious practices.

Elite warriors became an important new source of patronage for religious arts, while the imperial court and aristocratic clergy continued their sponsorship of sculpture workshops in Kyoto and Nara even as their fortunes gradually declined. One major new patron was Minamoto Yoritomo, who became the first ruling shogun and established a military government headquartered in the town of Kamakura in eastern Japan. Later in the thirteenth century, however, the continued threat of invasion by the Mongol empire created further instability. In 1333, a cunning Japanese emperor launched a rebellion ending the Kamakura shogunate not even 150 years after its founding.

Despite the brevity of this historical period, it had a lasting impact on the political, artistic, and religious legacy of Japan. Shoguns and warlords were the dominant rulers up until the mid-nineteenth century. Even in the eighteenth century, sculptors proudly traced their artistic lineages back to early Kamakura master sculptors, while religious movements established during the period continue to be some of the most popular forms of Buddhism practiced in Japan today.

Ive Covaci, Guest Curator

Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art, Asia Society

Purchase the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue at AsiaStore.

Sculptures of the Kamakura period can be strikingly realistic; the works have naturalistic body proportions and are carved with a sense of breath-filled volume. Buddhas (enlightened beings) and bodhisattvas (beings destined for Buddhahood who postpone it to assist others in reaching enlightenment) appear approachable, while fierce guardian deities possess a great sense of movement and dramatic facial expressions. The folds of draperies and details of clothing are rendered with convincing naturalism, and facial features often evoke real, human individuals.

Several factors contributed to the increased realism in sculpture of the period: joined-woodblock construction (employing multiple hollow blocks of wood for a single statue) allowed sculptors to portray more dramatic movement than in works carved from a single tree trunk. The use of inset crystal for the eyes was another important innovation that created a vivid sense of realism. Sculptors in the Nara area, working to restore icons lost to fire, revived and updated naturalistic eighth-century styles. Contact with China intensified during the early Kamakura period, and Japanese sculptors absorbed elements from Song-dynasty (960–1279) Chinese art, which also displayed greater naturalism during this time.

The Kamakura period saw the emergence of master sculptors with clear artistic identities. We know the names of these artists from signatures on works, a practice which increased significantly in this period. The Standing Shaka Buddha, Fudō Myōō, and Standing Jizō Bosatsu in this section were all made by the master sculptor Kaikei (active ca. 1183–1223), one of the most renowned artists of the period, whose style was widely imitated by later sculptors. Competition for patronage was fierce, and artists completed commissions for a wide variety of patrons and religious institutions. But as inscriptions and documents reveal, sculptors were also themselves devotees of Buddhism and of the deities they so beautifully rendered in material form.

Sculptors and Their Workshops

This exhibition includes a number of signed works by master sculptors and other works that can be attributed to specific artists or their workshops. Most of these artists belonged to the innovative Kei school, a major driver of stylistic change and increased naturalism in the Kamakura period.

Sculptors emphasized their artistic lineage through their assumed names. Disciples—often blood relatives—incorporated characters from previous master sculptors’ names as part of their own. The character “kei 慶” in Kei school comes from the sculptor Kōkei 康慶 (active 1152–1196), who established the school in the Nara area. The same “kei” was also used by his successor, Kaikei 快慶 (active ca. 1183–1223), and the sculptor Jōkei 定慶 (1184–1256).

The Zen school, whose sculptors use the character “zen 善” in their names (different from Zen 禅 Buddhism), emerged in the Nara area during the early decades of the thirteenth century. Zen-school sculptors are known for their great technical skill and for the approachable sweetness characterizing many of their works.

Sculptors frequently collaborated on works, even on small statues, with a master sculptor leading the project. The inscriptions inside two Jizō figures by Kaikei and Zen’en include the names of their associates and sons. Illustrious sculptors were granted honorific ecclesiastical titles and ranks, which they incorporated in their signatures. Some sculptors also adopted devotional names; Kaikei’s signature on a Jizō reads “An’amidabutsu,” which refers to his faith in the Buddha Amida.

Zen’en (1197–1258).Jizō Bosatsu. Kamakura period, ca. 1225–26.Japanese cypress (hinoki) with cut gold leaf and traces of pigment, inlaid crystal eyes, and bronze staff with attachments. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.202a–e. Photography by Synthescape

The interior of this small, elegant image of Jizō Bosatsu bears the signatures of Zen’en and several other sculptors, along with the names of prominent monks of the Kōfukuji temple in Nara, presumed to be the patrons. The inscription also establishes that this Jizō, a Buddhist icon on the exterior, is associated with worship of the native Japanese gods at Kasuga shrine in Nara, which formed a shrine-temple complex with Kōfukuji. Two other statues closely related to this Jizō are still extant in Japan, and Zen’en likely created them all as part of a set of five Buddhist images corresponding to the five native deities of Kasuga.

Kaikei (active ca. 1183–1223). Fudō Myōō. Kamakura period, early 13th century. Lacquered, polychromed, and gilded Japanese cypress (hinoki) with cut gold leaf (kirikane) and inlaid crystal eyes. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015 (2015.300.252). Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource.

Fudō Myōō, whose name means “the immovable Wisdom King,” is an important deity in esoteric Buddhism. Iconographic tradition dictates the child-like proportions and fierce expression of Fudō, who has the power to destroy obstacles to enlightenment. In the Kamakura period, however, images of this deity were imbued with a new sense of naturalism, as seen in the modeling of the chest and articulation of the waist in this work. Although unsigned, this Fudō is attributed to the sculptor Kaikei based on style; a nearly identical sculpture signed by him is in the Sanbō-in temple in Kyoto.

Technical Innovations

Two important technical innovations furthered the realistic approach to sculpture in the Kamakura period.

Joined woodblock construction (yosegi zukuri): While sculptors in ancient Japan used a single tree trunk for the main body of icons, in the mid-eleventh century they began using multiple blocks of wood carved and hollowed out separately and then assembled to create a single, large sculpture. By the Kamakura period, this technique, called “joined woodblock construction,” was widely used even for small works. This allowed for greater flexibility in depicting naturalistic and dramatic movement of the body, since the icon’s form was not constrained by the log’s initial size. Once assembled, the wooden sculpture was coated with lacquer and then painted or gilded.

Gushōjin. Kamakura period, 13th century. Wood with traces of pigment. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975 (1975.268.700a–c). Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource.

Although small, this sculpture was created with the true joined woodblock construction technique (yosegi zukuri) using separate pieces for the left and right sides of the body, the arms, sleeves, hands, and the protruding fabric of the robe in the front. The naturalistic carving and powerful stance, best viewed from all angles, demonstrates the dynamism of Kamakura-period sculpture. The figure is thought to represent Gushōjin, a deity that records the good and bad deeds of every person throughout his or her lifetime for judgement after death by the King of Hell. This Gushōjin is dressed as a Chinese official, reflecting how such beliefs entered Japan from China in the late Heian period.

Inset rock-crystal eyes (gyokugan): The use of crystal inserts for the eyes of wooden sculptures was a mid-twelfth-century innovation, attributed to Kei-school sculptors of Nara. Socket-like openings for the eyes were created in the hollowed-out head of the statue. Lens-shaped pieces of crystal were painted on their concave sides with pupils and irises, sometimes outlined in gold or red, and backed with white paper. The crystal eyes would then be inserted into the sockets from the inside of the head, secured with a wooden strip held in place by pegs. The crystal would reflect the firelight of temple interiors, making the sculpture’s eyes glitter and greatly enhancing the work’s life-like presence.

Kōshun (active 1315–1328). The Shinto Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk. Kamakura period, dated 1328. Polychromed Japanese cypress (hinoki) with inlaid crystal eyes. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Maria Antoinette Evans Fund and Contributions, 36.413. Photograph © 2016 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Although easily mistaken for a portrait of an actual monk, this sculpture represents Hachiman, the clan god of the Minamoto warrior family and the tutelary, or protective, Shintō deity associated with many Buddhist temples. An inscription on the interior of the head tells us that the sculptor was named Kōshun, held the rank of “eye of the law” (hōgen) and was a master sculptor of the Kōfukuji temple in Nara. Later in the fourteenth century, Kōshun also signed his works as a “descendant of the sculptor Unkei,” demonstrating the importance of tracing sculptural lineages in artistic identity in the Kamakura period.

Contact with China

The late twelfth century brought increasing diplomatic, commercial, and religious exchange with China, which contributed to stylistic and iconographic changes in Kamakura-period art. Chinese craftsmen were employed in rebuilding the great temples of Nara after their fiery destruction in the 1180s, and Japanese monks traveled back and forth, bringing Chinese texts, prints, and paintings to Japan. Artists like Kaikei observed and incorporated new elements from imported works into their sculpture.

Continental influence can be seen in the Chinese-style draperies, with fluttering hemlines and fluted sleeves, and towering, elegant topknots of some Japanese sculpture from this period.

The small Gushōjin in Chinese-style official robes in this section represents Chinese beliefs in the Kings of Hell, incorporated into Japanese Buddhism just prior to the Kamakura period. Devotees believed that individuals destined for rebirth in hell first encountered a Chinese-style court complete with kings who judged the dead and assigned their punishments. Numerous paintings of the Kings of Hell were imported from China during this period; Japanese artists copied the paintings and also reimagined the deities of the underworld as sculptural ensembles.

Circle of Higo Busshi Jōkei (born 1184–died after 1256). Bishamonten. Kamakura period, first half of 13th century. Polychromed and gilded Japanese cypress (hinoki) with cut gold leaf (kirikane) with inlaid crystal eyes and gilt-metal ornaments. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, L2015.33.269a-f. Bridgeman Images.

Bishamonten is the guardian king of the North, who appears as a fierce, armor-clad warrior trampling a demon, symbolic of his subjugation of evil. Kamakura-period records indicate that Bishamonten was worshipped for defense of the nation and success in battle by such people as Minamoto Yoritomo (1147–1199), the first Kamakura shogun. The Kei-school sculptor, Higo Busshi Jōkei, to whose circle this work is attributed, executed commissions for warrior patrons in eastern Japan as well as aristocratic patrons in the imperial capital of Kyoto. Jōkei and his circle often represented Bishamonten with highly realistic facial features, evoking the presence of a real individual rather than a distant deity.

Kamakura-period Buddhists believed that making or commissioning an icon generated spiritual merit and formed a bond with the deity, moving the devotee toward ultimate enlightenment. But worshippers also continually appealed to Buddhist deities for help with matters of this world. Icons were invoked for a wide variety of goals, illuminating the concerns and beliefs of the people who created them.

After production, icons are consecrated during the “eye-opening ceremony” (kaigen kuyō), a ritual including the symbolic painting in of the pupils that renders the icon spiritually potent. In temples, larger icons are encountered in ritual settings, multisensory experiences filled with the smoke and scent of incense, the chanting of monks, the ringing of bells and gongs, and the colors and forms of icons and offerings. Ritual implements were arranged on altars and manipulated by monks. Tiny icons, housed in miniature shrines, served as the objects of personal devotions in more intimate settings. A person might even spend the final moments of his or her life in the presence of sculpture, as devotees prayed before icons of Amida Buddha to be welcomed into his paradise after death.

In Kamakura-period religious developments, both traditional and new practices competed and combined in innovative ways. Established temples around Kyoto continued performing state-sponsored and privately-commissioned secret esoteric rites. Renewed devotion to the historical Buddha was championed by monks in the Nara area and beyond. Devotional movements focused on individual deities gained momentum and spread throughout the population. Zen Buddhism, which stresses seated meditation and discipline as the way to realizing enlightenment, arrived from China and gained patronage by elite warriors in eastern Japan and courtiers in the capital alike. Worship of the native Japanese deities (kami) continued and intermingled with the worship of Buddhist deities. The diversity of imagery shown in this exhibition attests to the Kamakura period’s fertile combination of doctrines and practices from all of these traditions.

Ritual Scepter (Vajra). Kamakura period, 14th century. Gilt bronze. John C. Weber Collection. Image courtesy of the collector.

Rather than the prongs that form the ends of most vajra, this example terminates in clusters of wish-fulfilling jewels framed by finely rendered openwork flames. A common iconographic symbol in Kamakura-period Buddhist art, the jewels represent abundance and fecundity, while the flames convey the power to consume the passions and burn off desire. Associated with Buddhist relics, wish-fulfilling jewels are held by many deities, Nyoirin Kannon and Jizō among them. As ritual implements, vajra on trays would be placed directly in front of the practitioner on the altar before the icon.

Esoteric Buddhism

In esoteric Buddhism, doctrines and practices are transmitted secretly from master to disciple through initiations. During ritual, the practitioner visualizes and aims to achieve unity with the main object of worship, and then extends the benefits of the rite to others. Esoteric rites were also frequently performed for specific worldly aims, including conquering enemies, gaining material fortune, healing illnesses, or conceiving and safely birthing children. The esoteric practices of the Shingon and Tendai schools, which had been the dominant forms of Buddhism since they were brought to Japan from China in the early ninth century, continued to flourish in the Kamakura period.

The esoteric pantheon encompasses a host of deities, including cosmic buddhas and bodhisattvas as well as wrathful deities with multiple heads and limbs, like the magnificent Daiitoku Myōō from the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Beyond sculptural and painted icons, the ritual environment includes altar tables with incense burners, offering stands, and ritual implements. Many icons likewise hold such implements in their hands: the cast iron Zaō Gongen, from the John C. Weber Collection, holds a thunderbolt (vajra), while the Asia Society Nyoirin Kannon would have delicately balanced a wheel (rinbō) on its upward pointing finger.

Daiitoku Myōō (Wisdom King of Awe-inspiring Power). Kamakura period, second half of 13th century. Wood with metal, polychrome, gilding, and inlaid crystal eyes. Minneapolis Institute of Art: Gift of the Clark Center for Japanese Art & Culture; formerly given to the Center in 2000 in honor of Dr. and Mrs. Sherman Lee by the Clark Family in appreciation of the Lees’ friendship and help over many years, 2013.29.1a–g. Bridgeman Images.

Daiitoku Myōō is one of the Five Wisdom Kings worshipped in esoteric Buddhism, serving as the wrathful manifestation of the Buddha Amida. Daiitoku was also worshipped for benefits in this world, for example being invoked for military victory in the conflicts that ushered in the Kamakura period in the twelfth century. The figure displays the wide chest, articulated waist, and muscular physique of Kamakura-period images of fierce deities. The expressive bull supporting Daiitoku is original to the work, a rarity among sculptures dating to this period. An inscription on the interior of the main head documents restorations completed to ensure that the icon would remain a sacred whole throughout the centuries of its use.

Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism teaches that devotion to Amida Buddha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, will ensure rebirth in his paradise and escape from the endless cycle of reincarnation. At the moment of death, Amida is believed to descend and welcome the devotee’s soul for rebirth on a lotus blossom in the Pure Land. Pure Land doctrines had entered Japan from China during the centuries before the Kamakura period, finding many adherents among the aristocracy and clergy. In the early Kamakura period, however, charismatic monks broke with the establishment to start new movements based on the exclusive practice of the nenbutsu, the recitation of the name of Amida Buddha, as the only possible path to salvation. Such movements found popular appeal as an accessible path to salvation open to varied social classes.

Pure Land beliefs gave rise to new types of art; as opposed to seated forms predominant in earlier periods, the standing form of Amida implies an active and immanent presence of this Buddha before the devotee. Amida worship was also popular among sculptors; Kaikei, who signed his works with “An’Amidabutsu” in reference to his Pure Land faith, created a large number of standing Amida images, and his style was widely imitated in the period.

.jpg)

Descent of Amida Buddha with Twenty-five Bodhisattvas (Amida Nijūgobosatsu Raigō-zu). Kamakura–Nanbokucho period, 14th century Ink, color, and gold on silk. Seattle Art Museum: Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection, 34.117. Courtesy of Seattle Art Museum.

Paintings of the “welcoming descent” (raigō) visually narrate the belief that the Buddha Amida will descend from his paradise at the moment of death to greet his devotees for rebirth in that Pure Land. Like standing icons of Amida, movement-filled diagonal compositions of the welcoming descent became popular in the Kamakura period. In the lower right corner, the bodhisattva Kannon kneels before the veranda proffering a golden lotus dais; the absence of a painted devotee, however, invites viewers to insert themselves into the drama, visualizing their own rebirth. The tiny, golden Buddhas floating above the dwelling are visual manifestations of the recitation of Amida’s sacred name (nenbutsu).

Zaō Gongen. Kamakura period, 13th century. Iron. John C. Weber Collection. Photography: John Bigelow Taylor.

Zaō, the deity represented by this small but powerful icon, is a fierce manifestation (gongen) of the Buddha. His appearance and attributes are similar to those of esoteric Wisdom Kings seen elsewhere in this exhibition, but unlike them, Zaō is a uniquely Japanese manifestation. As the local deity of Mount Kinpu in the Yoshino range near Nara, he is worshipped as the primary deity of the Shugendō tradition. This syncretic form of worship, which thrived in the Kamakura period, combined native mountain worship traditions, ascetic practices, and esoteric Buddhist iconography and ritual. The dynamic sense of movement in this rare cast-iron statue reflects the technical brilliance of Kamakura-period sculpture.

Nyoirin Kannon. Kamakura period, early 14th century. Japanese cypress (hinoki) with pigment, gold powder, and cut gold leaf (kirikane). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.205. Photography by Synthescape.

Nyoirin Kannon, an esoteric form of the bodhisattva of compassion, is named for the wish-fulfilling jewel (nyoi hōju) and the wheel (rinbō), which would have been held in two of his six hands, the wheel balanced atop the pointing finger, and the jewel held in front of his chest. In the Kamakura period, the wish-fulfilling jewel was associated both with Buddhist relics, creating a symbolic link to the historical Buddha, and with the Japanese imperial regalia. Nyoirin Kannon was therefore invoked in rites for the protection of the sovereign, and became identified with several native Japanese deities, including Amaterasu, the sun goddess of the imperial clan.

The interiors of sculptures reveal a fundamental way that icons were “enlivened” and imbued with sacred power. The practice of placing deposits inside Buddhist sculptures is ancient, but the Kamakura period saw a significant increase in the frequency and quantity of such deposits. Joined woodblock construction created larger hollow interiors and sacred deposits were believed to render the icon more powerful. The Jizō Bosatsu from the Cologne Museum of East Asian Art is a rare example in western collections of a statue still accompanied by its original contents.

Statues with interior deposits could contain a variety of objects, including miniature icons, scriptures, reliquaries, and devotional prints of various deities. Dedicatory documents listed the patrons, artists, and devotees forming a “karmic bond” with the icon. Inscriptions written directly on the interior walls of statues could also include sacred syllables and incantations.

The worship of relics, small grains that represented the corporeal remains of the Buddha, flourished in the Kamakura period. Relics were often placed inside statues contained within miniature reliquaries, such as the crystal pagoda-shaped one seen in this gallery. As well as evoking the Buddha’s presence, relics were considered to have magical properties and helped sanctify the icon.

Throughout the history of Japanese Buddhism, certain famous statues were considered embodiments of the “living Buddha” and capable of working miracles. The temples enshrining these icons attracted large numbers of pilgrims, even if the statues themselves were often concealed from view. Replicas of miracle-working statues were produced in abundance in the Kamakura period. Far from mere formal copies, the replicas were believed to possess the sacred essence of the original.

Zenkōji Amida Triad. Kamakura period, 13th–14th century. Bronze. John C. Weber Collection. Photography: John Bigelow Taylor.

This cast-bronze triad of the Buddha Amida flanked by the bodhisattvas Kannon and Seishi is a beautiful example of the many replicas of the famous and hidden triad at Zenkōji temple in Nagano prefecture. This temple was the focus of a thriving pilgrimage cult in the Kamakura period since the concealed icon was considered a “living manifestation” of Amida, capable of working miracles. Many legends are told about the original icon, including that it floated to the shores of Japan from Korea in the sixth century. Zenkōji-style Amida triads often evoke archaic styles of sculpture; however, in this example, Kamakura-period stylistic elements include the broad shoulders and well-modeled chest of the central figure, and the tall hairstyles of the bodhisattvas, rendered in the Chinese Song-dynasty style.

Reliquary (gorintō). Kamakura period. Rock crystal. Seattle Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. John C. Atwood, Jr., 56.247. Courtesy of Seattle Art Museum.

This reliquary is made of rock crystal, the same material commonly used for the inset eyes of Kamakura-period sculptures. The shape is called a five-element stupa (gorintō), an esoteric form where each of the five geometric shapes represents one of the five elements: earth, water, fire, wind, and space. The five-element stupa represents both the body of the Buddha and the body of the practitioner, which esoteric Buddhist ritual aims to unify. Frequently, such reliquaries were enshrined inside statues, and the symbolic form of the five-element stupa was also used for gravestones in the period.

.jpg)

The Buddha Illuminates the Universe; Frontispiece Illustration to a Handscroll of the Lotus Sutra (Myohōrengekyō). Kamakura–Nanbokucho period, 14th century. Gold and silver ink on dark-blue paper. Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations: Spencer Collection (Sorimachi 19), 3018. Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library.

The Lotus Sutra, the most popular Buddhist scripture in Japan, was often enshrined inside sculptures as a “dharma relic,” standing for the teachings of the Buddha, just as corporeal relics represent his body. The text of the Lotus Sutra directs its devotees to reproduce and ornament the scripture, which could take the form of luxurious productions in gold and silver on indigo-dyed paper. The frontispiece begins with the Buddha preaching the scripture and illuminating the world, followed by devotees painting and sculpting Buddha images and venerating stupas (reliquaries). Other scenes include the apparition of a many-jeweled stupa and the dragon princess presenting a precious jewel to the Buddha.

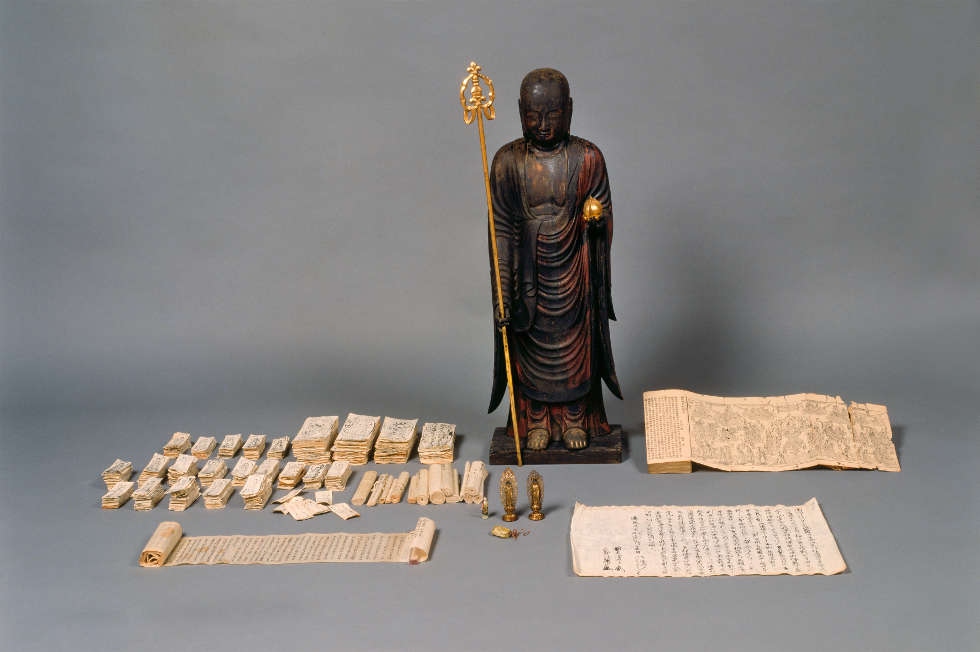

The Jizō Bosatsu from the Cologne Museum of East Asian Art and Its Contents

During conservation treatment in the 1980s, a sculpture of Jizō Bosatsu was opened and found to contain a remarkable assortment of items inserted at the time of the icon’s consecration. A document among these contents describes the circumstances of the icon’s production and names the sculptor, Kōen (1207– after 1275). Some of the most significant deposits are:

• A silk brocade bag containing a grain considered to be a relic of the Buddha.

• Two miniature gilt bronze statues, one of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni and the other of Amida Buddha, found inside the head of the sculpture. These miniature icons are modeled after famous statues considered to have miraculous powers, and were likely intended to transfer the sanctity and power of the originals into the newly created Jizō statue. A miniature wooden Jizō statue was also included, but not listed in the inventory.

• Thousands of printed images of Amida and Jizō on small vertical strips of paper, many inscribed with the names of individual donors. These served a devotional purpose in linking the donors with the icon in a “karmic bond,” and helped in fundraising for the making of the icon.

• Several Buddhist scriptures, including a Chinese printed accordion-fold book of the Lotus Sutra and two handwritten scrolls of the Sutra of Brahma’s Net. Scriptures represent the Buddha’s teachings, and as material objects they were considered “dharma relics” also evoking the presence of the Buddha.

• Printed esoteric incantations (dharani). Dharani are combinations of Sanskrit syllables, without semantic meaning, but whose sounds and written forms were considered to have protective or magical efficaciousness.

Kōen (1207–after 1275). Jizō Bosatsu and Selected Contents. Kamakura period, dated 1249. Sculpture: Japanese cypress (hinoki); Contents: paper, gilt bronze, silk, and wood. Museum of East Asian Art Cologne, RBA, in.nr. B11,37. Photo: © Theinisches Bildarchiv Köln, Sabrina Walz: rba_c004107.

According to a document found inside this statue, the Kei-school sculptor Kōen created this Jizō in conscious imitation of an earlier statue, believed to have miraculous powers, that was the personal devotional icon of the Pure Land Buddhist patriarch Genshin (942–1017). This perhaps accounts for the sculpture’s archaistic style, which departs from Kōen’s more naturalistic approach in his other known works; indeed, before the dedicatory document was discovered inside the sculpture this statue was presumed to date to the early eleventh century.

Kamakura: Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan is made possible by the generous support of The National Endowment for the Arts.

Major support for this exhibition is also provided by the Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation and Etsuko O. Morris and John H. Morris Jr.

Asia Society acknowledges other generous underwriters including The Kitano Hotel New York, the Japan Foundation, The Blakemore Foundation, Peggy and Richard Danziger, Japanese Art Dealers Association, Helen Little, Toshiba International Foundation, John C. Weber, and the Ellen Bayard Weedon Foundation.

Additional support is provided by Sebastian Izzard, Dian Woodner, Leighton R. Longhi, Joan B. Mirviss, and Erik Thomsen.

MEMBERS-ONLY LECTURE

Kamakura: Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan

Tuesday, February 9 • 6:30 pm

Join guest curator of Kamakura: Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan, Ive Covaci for an inside view of the exhibition and its exploration of how sculptures are “brought to life” or “enlivened” by the spiritual connection between exterior form, interior contents, and devotional practice, reflecting the complexity and pluralism of the period.

SYMPOSIUM

Empowering Objects: Kamakura-period Buddhist Art in Ritual Contexts

Friday, February 26 & Saturday, February 27

Held in conjunction with the exhibition, Kamakura: Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan, this major multidisciplinary symposium brings together scholars and experts in art history, religious studies, musicology, and Japanese history to examine the multifaceted artistic traditions and spiritual practices that flourished during the Kamakura period.

LECTURE & DEMONSTRATION

Theater Japan / NOH and KYOGEN

Sunday, February 28 • 6:30 pm

This program is a rare opportunity to see Noh and Kyogen together on one stage through an intimate demonstration and talk by master artists. It illustrates the importance of traditional Japanese theater through different classical forms.

FILM SERIES

Of Ghosts, Samurai, and War: A Series of Classic Japanese Film

Friday, March 4 –Saturday, March 19

With a history spanning more than 100 years, Japanese cinema has produced some of the most admired films that continue to enrich the world cinema discourse. Japan Foundation’s Film Library is indisputably one of the most important archive of Japanese films in the world. Asia Society partners with Japan Foundation to uncover rarely screened 35mm film gems from the Film Library to share with New York audiences.

PERFORMANCE

Recycling: Washi Tales

Thursday, March 24–Friday, March 25

Recycling: Washi Tales brings to life the human stories linked to a sheet of washi (Japanese handmade paper) as it is recycled through time. Four tales of papermaking from different periods of Japanese history unfold on stage with an extraordinary ensemble of performers and musicians in a world created by distinguished paper artist Kyoko Ibe.

PERFORMANCE

Japanese Kyogen Theater

Thursday, April 14

Kyogen is a form of traditional Japanese comedic theater which balances the more solemn form of Japanese theater called Noh. It was originally developed to provide comic relief between heavier, more serious Noh acts.

BOOK PROGRAM

Monkey Business: Japan/America Writers' Dialogue

Saturday, April 30 • 2:00 pm

An annual conversation between contemporary Japanese and American authors selected and moderated by the cofounders and editors of the Tokyo-based literary journal Monkey Business, the program features writers published in the latest volume.

FILM PROGRAM

New York Japan CineFest

Thursday, June 2 & Friday, June 3

An annual festival of short films by Japanese and Japanese American filmmakers with a focus on young talent, this rich offering of films includes documentary, animation, live action, and experimental shorts.

All programs are subject to change. For tickets and the most up-to-date schedule information, visit AsiaSociety.org/NYC or call the box office at 212-517-ASIA (2742) Monday through Friday, 1:00-5:00 pm.

We welcome student groups from the third-grade through university. Arrange a tour and a teaching docent will lead the group through the exhibition and engage students on this fascinating subject.

Schedule a tour

Download Teachers guide (PDF, 2.85 mb).

Plan Your Visit

725 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10021

212-288-6400