- Overview

- The Densatil Monastery

- The Tashi Gomang Stupas

- Tier of Protectors of the Teachings

- Tier of Offering Goddesses

- Tiers of Tantric Meditational Deities

- Lineage Tier and the Uppermost Stupa

- Pillars, Columns, and Embellishments

- Art Historical Influence and Meaning

- Das and Tucci

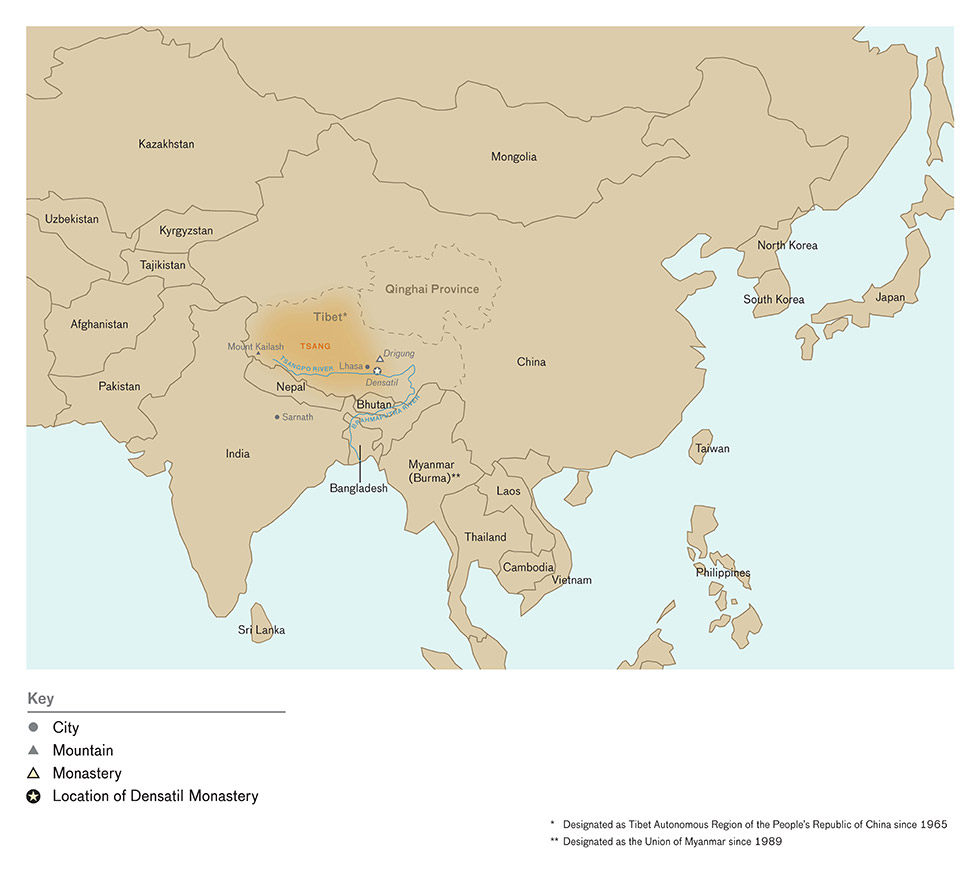

- Maps

- Selected Glossary of Terms

- Timeline

- Videos & Blog Posts

- Catalogue

- Related Programs

- Credits

- Press

- Free Audio Guide

- Overview

- The Densatil Monastery

- The Tashi Gomang Stupas

- Tier of Protectors of the Teachings

- Tier of Offering Goddesses

- Tiers of Tantric Meditational Deities

- Lineage Tier and the Uppermost Stupa

- Pillars, Columns, and Embellishments

- Art Historical Influence and Meaning

- Das and Tucci

- Maps

- Selected Glossary of Terms

- Timeline

- Videos & Blog Posts

- Catalogue

- Related Programs

- Credits

- Press

- Free Audio Guide

"Enthralling"

— The New York Times

The Densatil Monastery has long been considered one of the great treasures of Tibet. Constructed at the end of the twelfth century in a remote, rocky area of central Tibet, this Buddhist monastery was most famed for its special stupas—reliquaries that housed the remains of venerated Buddhist teachers. The stupas at Densatil were of a type called tashi gomang (Many Doors of Auspiciousness). They were multi-tiered, sculptural gilt copper structures that stood more than ten feet tall and were resplendent with inlays of semiprecious stones. Prior to the destruction of Densatil during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1978), eight of them dating between 1208 and 1432 stood in the Monastery’s main hall. This pioneering exhibition brings together statues and panels from international public and private collections to give us a sense of the grandeur of the memorial structures that once stood at Densatil.

Followers of the charismatic Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo (1110–1170) constructed the Densatil Monastery. There are many schools of Buddhism in Tibet. His school, which came to be known as the Phagmo Drupa Kagyu school, was one of the four primary schools of the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. The Phagmo Drupa religious school and its noble house became so powerful in Tibet that they founded a dynasty that lasted from the mid-fourteenth to the mid-fifteenth century.

The Phagmo Drupa school lost power over time and had died out by the end of the seventeenth century, but the Densatil Monastery survived intact under the control of other Tibetan Buddhist schools until it was destroyed in the mid-twentieth century. Today the monastery is undergoing reconstruction thanks to the efforts of the Tibetan Autonomous Region Ministry of Culture and the Drigung (Drikung) Kagyu school.

The exhibited reliefs and sculptures are displayed along with photographs taken by Pietro Francesco Mele, who accompanied the scholar and explorer Giuseppe Tucci to Tibet in 1948, and we are able to see again how they would have once appeared on a tashi gomang stupa. Golden Visions of Densatil provides us with a compelling glimpse of truly innovative and masterly artistry.

Olaf Czaja, Guest Curator

Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art

A sand mandala was created at Asia Society, New York, on the occasion of this exhibition.

In his youth, Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo (1110–1170) traveled from his home in eastern Tibet to central Tibet to pursue his religious studies. After his full ordination at the age of twenty-four, he studied under many teachers from different Buddhist schools. Gampopa Sonam Rinchen (1070–1153), a student of the famous Tibetan yogi and poet Milarepa (1040–1123), had a particularly lasting influence on Dorje Gyalpo’s spiritual development. After his studies with this teacher, and years of teaching on his own, Dorje Gyalpo went into retreat. He found solitude in Phagmodru, which means “Sow Crossing,” where the local ruler of the area supported him and he found shelter in a thatched hut. Many of Dorje Gyalpo’s former students followed him to Phagmodru, where he came to be known as Phagmo Drupa (The One of Phagmodru).

When Phagmo Drupa passed away in 1170, the monks in Densatil performed the funeral ceremonies for their deceased teacher and cremated him. According to old customs, his tongue, untouched by the flames, was cut into two parts. One part remained in Densatil; the other was sent back to his home region. His heart was removed and placed in a newly built stupa called a tashi wobar stupa, or stupa of “Radiating Light of Auspiciousness.”

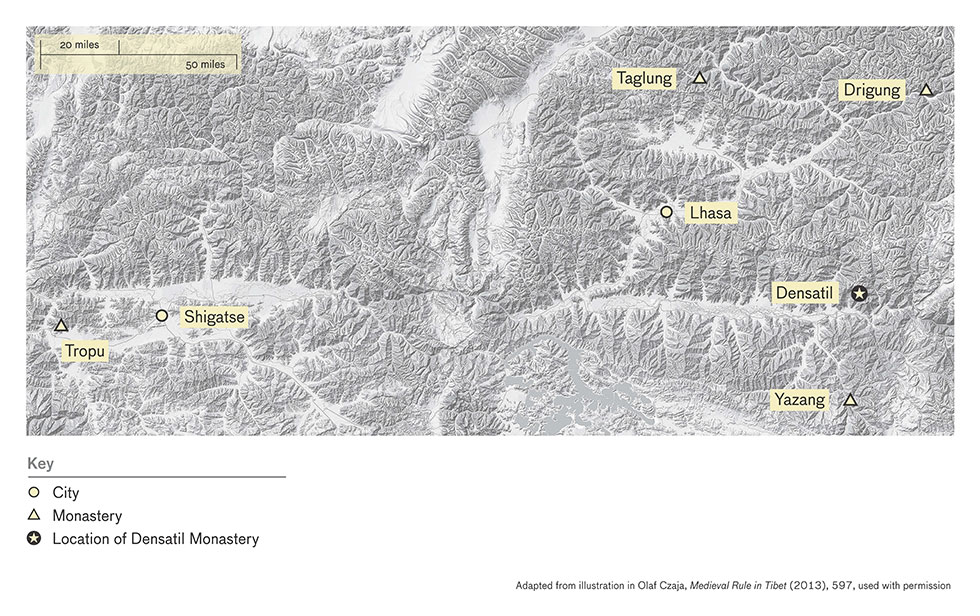

In 1198, followers of Phagmo Drupa held a large meeting to begin the process of constructing a monastery. They agreed that a main hall should be built around their teacher’s thatched hut. Each student together with his entourage was responsible for a portion of the building. The geographic home region of each pupil corresponded with the geographic orientation of the wall that they worked on. The main hall also was conceived of as a mandala, a kind of cosmic chart and meditational device. The five buddhas—Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, Amoghasiddhi, and Vairochana—were associated with the main hall’s four walls and center, respectively. After the structure was completed, major religious objects were arranged inside according to the four cardinal directions. Other smaller buildings were most likely erected beside the main hall.

Floor plan of the main hall of the Densatil Monastery

1. Western main gate

2. Western side gate

3. Central area

4. Stupas and statues

5. Platform with the thatched hut of Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo

6. Chapel of the Teachers

7. Northwestern corner chapel

Illustration: Olaf Czaja, courtesy of Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften

Eight towering memorial stupas known as tashi gomang, or “Many Doors of Auspiciousness,” were located in the main hall of the Densatil Monastery. One of Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo’s former students, Jigten Gonpo (1143–1217), experienced a marvelous vision that inspired the iconography and design of these structures. Jigten Gonpo had briefly served as head of the Phagmo Drupa congregation after the death of its master. He then went to Drigung where he founded a monastery. One day, he had a vision while meditating. He saw the snow-capped peak of the holy Pure Crystal Mountain in Tsari with the deity Chakrasamvara standing in a heavenly palace and surrounded by a retinue of 2,800 deities arranged like a tashi gomang stupa. Following this experience, Jigten Gonpo invited artists from Nepal to the Drigung Monastery to help create a tashi gomang stupa. When the elaborate structure was completed around 1208, Jigten Gonpo requested that the tashi wobar stupa containing the remains of Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo be brought from the Densatil Monastery and placed on top to complete the tashi gomang stupa. Ultimately, however, the students protested the removal of their master’s remains from Densatil and the tashi wobar stupa was returned.

The first tashi gomang stupa built at Densatil contained the remains of the abbot Dragpa Tsondru (1203–1267). The expense of constructing these complex works of art made it impossible to erect one for each of the Densatil abbots. The tashi gomang stupa fragments reveal the high level of craftsmanship required to model, cast, gild, inlay, and assemble these structures. Despite their complexity, seven more tashi gomang stupas were built for Densatil abbots over the following centuries: one in the thirteenth century, three in the fourteenth century, and three in the fifteenth century. The stylistic variations seen in the fragments attest to the many hands that created these tashi gomang stupas over time.

In both the Drigung and Densatil monasteries, the iconographic program created by Jigten Gonpo laid the foundation for the tradition of constructing tashi gomang stupas, although some additional deities were added to later stupas. Thanks to Sherab Jungne (1187–1241), who wrote a description of the tashi gomang stupa created for Phagmo Drupa at Drigung, we are relatively well informed about the appearance of the first structure inspired by Jigten Gonpo’s vision and those that were later created at Densatil.

The name “tashi gomang” may be translated as “Many Doors of Auspiciousness.” The middle section of a tashi gomang stupa comprises several levels showing a number of niche-doors in every direction. These memorial stupas consisted of a multi-tiered tashi gomang structure topped by a stupa that contained the remains of a Buddhist adherent. Tashi gomang stupas at Densatil were adorned with thousands of deities to commemorate deceased abbots who attained enlightenment like the Buddha.

The basic structure of a tashi gomang stupa can be described as follows:

A magnificent lotus flower rose up from the bottommost tier, or the “pool,” to accommodate a structure of different tiers. The tiers were recessed and stepped, accentuating the central axis of the structure. They were adorned on all sides with numerous free-standing deities and panels with deities represented in relief. The deities depicted were arranged according to their sanctity: the higher they were placed on the structure, the higher their religious status. From bottom to top the tiers were the Tier of Protectors of the Teachings, the Tier of Offering Goddesses, the Tier of Buddhas, the Tiers of Tantric Meditational Deities, and the Lineage Tier.

Tashi gomang Stupa as Mandala

A tashi gomang stupa was created as a huge, three-dimensional mandala. As seen in the diagram above, the outline of a mandala is clearly recognizable from the bird’s-eye view of a tashi gomang stupa. An alternating pattern of vajras and three jewels formed a decorative ring around the outermost edge of the structure. We can imagine that the circle of light, which usually forms the outer circle of a mandala, was formed by the butter lamps that encircled tashi gomang stupas. A model of a divine palace was situated within the center of these circles, erected on an adamantine cross called a vishvavajra that was formed by two crossed vajras. The gates of the model of the divine palace were lined up with each cardinal direction and corresponded to the central section of each tier of the tashi gomang stupa. The different tiers or steps represent stages on the path towards enlightenment—successive teachings, which are sculpturally represented by images and symbols. The highest level, represented by the center of this diagram, was occupied by a stupa containing the remains of a late abbot. It symbolizes the highest spiritual attainment.

The spiritual metaphor within the design of a tashi gomang stupa may also have been experienced by an adherent who stood in front of such a stupa and presented offerings, or a pilgrim who circumambulated it ritually. He would have been reminded that he was still trapped in the endless cycle of birth and death and that only by following the Buddhist teachings could he escape pain and suffering, and find enlightenment.

Ritual Direction vs. Geographic Direction

In this exhibition the direction of imagery on tashi gomang stupas refers to Tibetan ritual directions, which are distinct from geographic directions. The front side of a tashi gomang stupa was the ritual eastern side, regardless of its geographic direction. If a viewer stood facing the front side of a tashi gomang stupa, the ritual southern side would be to the viewer’s left, and the ritual northern side would be to the viewer’s right. The back side of the tashi gomang stupa would be the ritual western side.

Adapted from illustration in Olaf Czaja, Medieval Rule in Tibet, 577-580, used with permission

The lowest, or sixth, tier of a tashi gomang stupa was the Tier of Protectors of the Teachings. Believers expected concrete help and assistance from the guardians on this tier. These powerful guardians of the faith are considered still part of the world of samsara, the cycle of life and death. They can grant wealth and help eliminate negative influences in a believer’s life, but they cannot offer enlightenment.

A base called the adamantine ground provided a foundation for the sixth tier and for the giant lotus flower that bloomed over the heads of the protectors. The double row of lotus petals served as a distinctive boundary that separated the lower, more worldly deities from the upper, esoteric ones. Guardians crowded around the rising lotus flower and were each encircled by a large vegetal scroll. They were carefully arranged with respect to the four directions. Four guardians of the directions stood outside a tashi gomang stupa and were arranged as a group on the eastern side of the structure.

Pairs of Nagarajas (Serpent Kings) were placed in the four intermediate directions on the sixth tier. Nagarajas were associated with both rain and wealth. They were also believed to guard the treasures contained within a stupa. Nagas, water spirits in the form of serpents, appeared along with Nagarajas on the sixth tier. They are often depicted with a human upper body and a lower body in the form of an elongated snake with a bent tail.

Pairs of deities also were placed on this tier in the four cardinal directions. Each pair consisted of a Mahakala, the fierce deity who protects Buddhist practitioners and helps them overcome obstacles, and a Shri Devi, a wrathful female deity. Additional dharmapalas—protectors of the Buddhist law that help practitioners avoid inner and outer obstacles they might encounter during practice—were placed between those pairs. Among the other deities found on this tier was Rahu, the leader of the Nine Planets, who was responsible for rain and the ripening of the harvest, as well as the deity Vaishravana, who promised wealth. Together these represented an impressive circle of powerful guardians to protect the Buddhist teachings and their followers.

Nagaraja. The Kronos Collections. Photograph by Richard Goodbody

Rahu. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the 1999 Collectors Committee (AC1999.58.1) Digital Image © 2013 Museum Associates / LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NY

Dhumavati Shri Devi. Asia Society, New York: Asia Society Museum Collection. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert H. Kinney in honor of Vishakha Desai. © 2013 John Bigelow Taylor Photography, Asia Society

Saptadashashirshi Shri Devi. Michael C. Carlos Museum of Emory University, Ester R. Portnow Collection of Asian Art, a Gift of the Nathan Rubin-Ida Ladd Family Foundation in honor of Anthony G. Hirschel, 2001.19.1. © Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. Photograph by Bruce M. White, 2007

Adapted from illustration in Olaf Czaja, Medieval Rule in Tibet, 577-580, used with permission

The Tier of Offering Goddesses, the fifth tier of a tashi gomang stupa, had a central panel occupied by three female deities and flanked on both sides by two groups of four dancing offering goddesses. In each of the levels of Tantric teaching, the visualization of symbolic offerings is important. Visualized during meditation by the practitioner, they manifest as lovely goddesses bringing offerings. On the fifth tier, the sixteen offering goddesses symbolize the offerings of form, taste, touch, and thought; of music, dance, and song; and of flowers, light, sweet perfume, and incense.

The triad of female deities included Parnashavari, who was placed in the middle and is believed to cure diseases and heal injuries. Marichi, thought to protect adherents from anxieties and fears, stood to her right; and Janguli, who adherents trust to help eliminate all kinds of physical and spiritual poisons, stood to her left.

Panel of Offering Goddesses. Collection of David T. Owsley. Photograph by Brad Flowers, courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art

Adapted from illustration in Olaf Czaja, Medieval Rule in Tibet, 577-580, used with permission

The fourth, third, and second tiers of a tashi gomang stupa consisted of Tantric meditational deities. The lowest of these tiers was a Tier of Buddhas where a specific buddha together with his entourage of bodhisattvas were depicted in each of the four directions. Each specific buddha was accompanied by other buddha figures placed in front of panels to its left and right. Many small buddha figures of alternating size and executed in relief adorned the panels. Some surviving fragments from these tiers have holes that most likely were made by nails that originally fixed the metal pieces to the internal wooden support of a tashi gomang stupa.

The two tiers above the Tier of Buddhas brought together various Tantric teaching cycles. At the stage of development represented by these tiers, the practitioner progressed by combining equal parts external ritual practice with inner cultivation of meditative concentration. In most cases on the Tiers of Tantric Meditational Deities, one panel represented one specific teaching cycle, but there were also some highly esoteric mandalas that spread across all of the panels. These included the Guhyasamaja mandala, consisting of thirty-two deities, on the eastern face of the stupa.

Manjushri. Somlyo Family Collection, USA. Photograph by David Godfrey

CBuddha Amoghasiddhi. Museum Rietberg Zürich, on long-term loan from The Berti Aschmann Foundation, BA 31. Photograph by Peter Schälchli

Guhyasamaja. Private Collection, Courtesy of John Eskenazi Ltd. Image courtesy of the collector

Buddha Akshobhya. Museum Rietberg Zürich, on long-term loan from The Berti Aschmann Foundation, BA 32. Photograph by Peter Schälchli

Adapted from illustration in Olaf Czaja, Medieval Rule in Tibet, 577-580, used with permission

Towards the top of a tashi gomang stupa, a wreath of lotus petals surrounded the tiers. This formed the outer edge of the topmost platform on which the stupa with the remains of the late abbot was placed. This stupa was surrounded by a number of statues of Indian and Tibetan teachers placed facing in all directions. Statues of the female meditational deity Vajravarahi were mounted at the edges of the platform to appear as if they were hovering in the sky.

For the Buddhist adherent, wisdom is achieved when the mind embraces emptiness and the lack of inherent existence of all phenomena. Having attained this, a practitioner achieved liberation from the pain and suffering of this world and attained full enlightenment. Enlightenment was symbolized by the stupa on top of the tashi gomang structure. Precious fabric covered with buddha images served as a back curtain for each tashi gomang stupa. Finally, a huge parasol, which was adorned with the representation of a mandala in half relief, was mounted above the whole tashi gomang stupa.

Vajravarahi. Museum Rietberg Zürich, on long-term loan from The Berti Aschmann Foundation, BA 109. Photograph by Rainer Wolfsberger

Kadam stupa. Rubin Museum of Art, New York, C2003.12.2. Photograph by Bruce M. White

Vajravarahi. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Board of Trustees in honor of Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, Senior Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art, 1970-95

Vajravarahi. Seattle Art Museum, Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection, 70.2. Photograph by Paul Macapia

Adapted from illustration in Olaf Czaja, Medieval Rule in Tibet, 577-580, used with permission

According to the inventory charts for the tashi gomang stupa built for Phagmo Drupa at the Drigung Monastery, there were eighty pillars on the stupa. Sixty-four of these had pillar figures and the rest were semicircular pillars. Pillars were an important component of all tashi gomang stupas and were both decorative and functional. As seen in the historical photographs of the main hall of the Densatil Monastery, the pillar figures have four arms and stand on lotuses in the tribhanga (triple bend) pose. These double-sided pillars depict a bodhisattva on one side and an offering goddess on the opposite side.

Pillars and columns placed at the corners of each panel on every tier supported the tashi gomang stupa architecturally. Trefoil embellishments with heavenly beings carrying offerings, however, were simply decorative. The craftsmen who created the tashi gomang stupas often incised Tibetan letters on different components as a way of numbering parts consecutively to aid installation. The location of the incised letters varies—sometimes the letters are found on the front of the pieces, sometimes on the back.

Trefoil embellishment. Rubin Museum of Art, New York, C2006.69.3. Photograph by David De Armas

Chakrasamvara with Footprints of Jigten Gonpo. Rubin Museum of Art, New York, C2003.7.1. Photograph by David De Armas

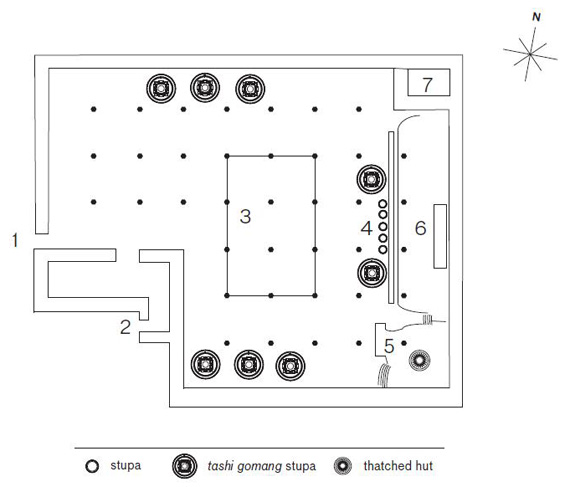

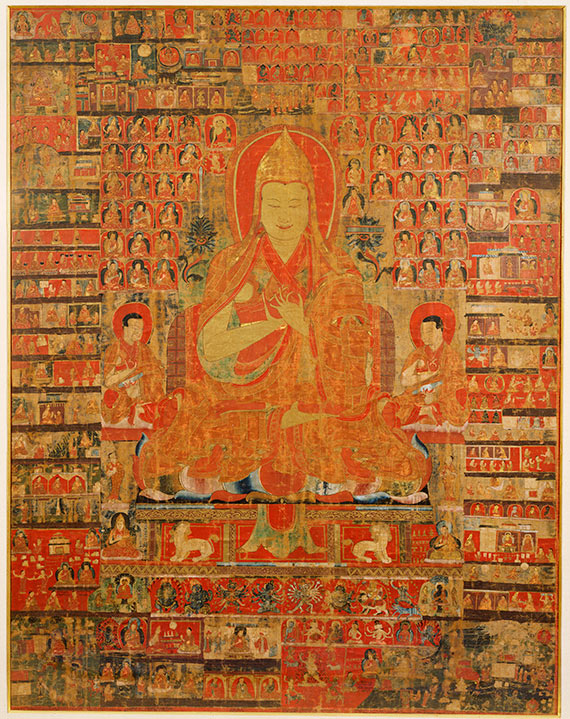

The architecture of tashi gomang stupas is highlighted in some early thangkas of the Drigung and Taglung schools, both branches of the Kagyu lineage to which the Phagmo Drupa school of Densatil also belongs. Important compositional elements also found on tashi gomang stupas are rendered in paint in thangkas. For example, at the bottom of these paintings there are crossed double vajras, symbolizing the adamantine ground, and vegetal scrolls encircle dharmapalas. Shared key elements like these suggest to a certain extent that these paintings may be regarded as two-dimensional representations of a tashi gomang stupa.

A record of the consecration of the tashi gomang stupa built for Phagmo Drupa is evidence of how elaborate these rituals were and points to how important they must have been both from a religious and political standpoint. The consecration comprised three main elements: the tapered, stylized parasols and the stupa’s finial, which depicted the sun and moon over a lotus bud; the stupa placed on top of the tashi gomang structure; and the tashi gomang structure itself. For the latter a complex construction was built: a huge sandalwood pillar richly adorned with silk ribbons served as a central axis. It was inserted and fixed into a vajra cross that decorated the foundation made of sandalwood. Intricate models that resembled divine palaces stood in the interior of the structure. Layers of religious items ranging from manuscripts related to the abbot’s school of thought and relics of important figures; to ritual implements; protective charms; precious powders like gold, silver, and beryl; fragrant materials like sandalwood; and medicinal substances filled the vast interior.

Every person who gazed at one of the completed tashi gomang stupas probably had the impression of looking upon a golden mountain. In fact, stupas in general are often compared to the cosmic Mount Meru, a comparison which also applies to a tashi gomang stupa. The practice of ritual circumambulation is also an important part of Tibetan pilgrimage when pilgrims circle the holy Mount Tsari or Mount Kailash, which also serve as physical representations of the cosmic Mount Meru. By circumambulating a single tashi gomang stupa or all the stupas housed within Densatil’s main hall by circling the building on the circumambulatory path outside its walls, an adherent could gain merit and move forward on the path to enlightenment.

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), the famous founder of the Gelug school, wrote a poem at Densatil in commemoration of his teacher Dragpa Jangchub (1356–1386). After praising the body of his teacher as similar to Mount Meru, he extols the tashi gomang stupa whose construction he had witnessed:

Being surrounded by statues which are beautiful in all ways

on all tiers of the sides filling all directions,

which are of sparkling luster of a clear brilliance,

these tashi wobar and tashi gomang

are, in their breath-taking sight, like Buddha Shakyamuni,

are, in their moving of big waves of blessing, like the ocean,

are, in their natural brilliance, like the lord of mountains Mount Meru,

as if the builders were piling up one beauty on another,

like stirring up the bees by a lotus grove and

the hares by white light and

the mind by a beautiful appearance,

these grasp the sentient beings’ hearts.

Translated by Olaf Czaja

Tsongkhapa (1357-1419). Rubin Museum of Art, New York, F1996.5.1. Photograph courtesy of the Rubin Museum of Art, New York

Descriptions of Densatil: Excerpts from the Journals of Sarat Chandra Das and Giuseppe Tucci

Today, with the help of Tibetan texts that date from as early as the first half of the thirteenth century, we are able to envision the Densatil Monastery that stood in central Tibet until the middle of the twentieth century. These writings provide us with both historical and anecdotal information about the Monastery. We are fortunate that a good deal of detail about the iconographic program for the first tashi gomang stupa at Drigung, the likely model for the tashi gomang at Densatil, still exists in the form of inventory charts (Dkar chag) written by Sherab Jungne (1187–1241). Even the contents of the interior of the Densatil Monastery are known to us as a result of an overview written by Chokyi Gyatso (1880–1923/25). Olaf Czaja has relied on these and other historical sources for the research that informs his enlightening essay in this catalogue. Although there are no extant Tibetan descriptions of the overall impression the Densatil Monastery and the splendor of its main hall made on adherents and visitors, happily we do have passages from the journals of two foreign scholar-explorers who visited Tibet and saw the Monastery before it was destroyed.

The first of these scholar-explorers to visit Densatil was Sarat Chandra Das (1849–1917). Born in eastern Bengal, Das studied engineering at the Presidency College in Calcutta. He began to learn the Tibetan language during his appointment as headmaster of Bhutia Boarding School in Darjeeling. By traveling with the school’s Tibetan language teacher, lama Ugyen-gyatso, he was able to obtain permission to enter Tibet and ultimately studied there for six months in 1879. He made a second visit in 1881, also accompanied by Ugyen-gyatso, and stayed for fourteen months. Das became a prolific Tibetan scholar following this second journey; his accomplishments included the translation of numerous texts from Tibetan to English, writings on Tibet’s pre-Buddhist history, and the compilation of a Tibetan-English dictionary. Das also played a role in what became known as the Great Game, the imperial struggle between Victorian Britain and Tsarist Russia for supremacy in regions from the Caucasus to China. Tibet was one of the places the British wished to explore and chart, in the hopes of preventing the Russians from finding alternate access to India that avoided the difficult Khyber Pass route. Aiding the British in this covert mission and disguised as an explorer, Das took copious notes on the areas he visited, including details about geography, distances, and altitudes. It is perhaps thanks to Das’s undercover work that we have his description of Densatil.

Giuseppe Tucci (1894–1984) studied at the University of Rome and traveled to Tibet almost thirty years after Das’s last journey there. A skilled linguist who had already learned Sanskrit and Chinese on his own prior to entering university, Tucci settled on Buddhist religion and its history as his primary field of interest. For more than twenty years this renowned Italian scholar documented and photographed Tibet and its civilization. Tucci first made his way to Ladakh in search of Tibetan texts in 1928. He was entranced by Tibetan culture and during his lifetime made eight expeditions to Tibet. For his 1948 expedition, Tucci engaged the photographer Pietro Francesco Mele to join his team and capture images of Tibet’s landscape and works of art. On that trip, Tucci and his associates copied inscriptions, collected important texts, and visited sites of religious and historical interest—including Densatil. He published notes about Densatil in his 1950 book A Lhasa E Oltre (To Lhasa and Beyond), one of his numerous publications.

By Adriana Proser

Photograph by Pietro Francesco Mele, 1948. © Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zürich, VMZ 402.00.0513

Photograph by Pietro Francesco Mele, 1948. © Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zürich, VMZ 402.00.1110

Photograph by Pietro Francesco Mele, 1948. © Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zürich, VMZ 402.00.1402

The above photos are not to be downloaded or reproduced in any way without the written permission of the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zürich. © Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zürich. All Rights Reserved.

Akshobhya (Sanskrit, Akṣobhya). “Unshakable”; One of the Five Buddhas. He presides over the east and heads the vajra family. His emblem is a vajra and his vehicle is an elephant, usually depicted on his throne.

Akshobhyavajra (Sanskrit, Akṣobhyavajra). “Unshakable Vajra”; A Tantric meditational deity.

Amitabha (Sanskrit, Amitābha). “Infinite Light”; One of the Five Buddhas. He presides over the west and his lotus family. A lotus is his emblem and a peacock is his vehicle.

Amoghasiddhi (Sanskrit, Amoghasiddhi). “Infallible Realization”; One of the Five Buddhas. He is the leader of the double vajra family occupying the north. The double vajra, a vishvavajra, is also his emblem. He is seated on a throne with a garuda bird.

apsara (Sanskrit, apsarā). Celestial female beings. In Tibetan art, they are portrayed as youthful and elegant figures that bring offerings to enlightened beings.

Ashtabhuja Tara (Sanskrit, Aṣṭabhuja Tārā). “Eight-armed Tara”; A special form of Tara with four faces and eight arms. She is said to be the mother of all buddhas from all times.

Avalokiteshvara (Sanskrit, Avalokiteśvara). “Lord who looks with compassion on suffering beings”; The Bodhisattva of Compassion, with many names and forms. He embodies universal compassion.

Chakrasamvara (Sanskrit, Cakrasaṃvara). “Wheel of Great Bliss”; The principal deity of the Chakrasamvara mandala.

Chaturbhuja Mahakala (Sanskrit, Caturbhuja Mahākāla). “Four-armed Mahakala”; A form of Mahakala especially venerated by followers of the Kagyu schools.

dakini (Sanskrit, ḍākinī). “Female Sky-goer”; A Tantric deity that often acts as consort to male meditational deities, but can also have an enlightened status of her own and serve as a solitary female meditational deity. Prominent examples are Vajravarahi and Vajrayogini.

devaputra (Sanskrit, Devaputra). “Son of the gods”; A celestial male being.

dharmapala (Sanskrit, dharmapāla). “Protector of the Law”; It is a designation for numerous, mostly wrathful, deities. They help a practitioner avert the inner and outer obstacles that he might encounter during his practice, but they can also be invoked to annihilate enemies.

Dharmavajra (Sanskrit, Dharmavajrā). “Indestructible Law Girl”; A four-armed Tantric goddess symbolizing the offering of thought.

Dhupa (Sanskrit, Dhūpā). “Incense Girl”; A two-armed goddess symbolizing the offering of incense.

Dhvajagrakeyura (Sanskrit, Dhvajāgrakeyūrā). “Banner-tip armlet”; A fierce goddess regarded as the destroyer of opposing forces and protector of her own forces.

Dipa (Sanskrit, Dīpā). “Lamp Girl”; A two-armed goddess symbolizing the offering of light.

Ging (Tibetan, Ging). A group of deities said to have been bound by oath to Padmasambhava. They are also guardians of the esoteric teachings of Vajrakila.

Guhyasamaja (Sanskrit, Guhyasamāja). “Secret Assembly”; A Tantric meditational deity, principal deity of the Guhyasamaja mandala. There are two main traditions: one regards the central deity as Akshobhyavajra, a form of Akshobhya; and the other as Manjuvajra, a form of Manjushri.

Hayagriva (Sanskrit, Hayagrīva). “Horse-necked”; A wrathful Tantric deity with several known forms. He possesses a small single or triple horse head on top of his head.

Jambhala (Sanskrit, Jambhala). A deity of wealth. Several forms exist including the Yellow Jambhala and the Black Jambhala.

Krishna Bhagavat Mahakala (Sanskrit, Kṛṣṇa Bhagavat Mahākāla). “Excellent Black Great Black”; A special form of Mahakala.

Mahakala (Sanskrit, Mahākāla). “Great Black”; Protector of the Buddhist teachings. A fierce deity who removes obstacles and destroys enemies. A variety of iconographic forms exist.

Mahamaya (Sanskrit, Mahāmāya). “Great Illusion”; A meditational deity. He possesses four faces and four hands and often appears together with his consort. He can be surrounded by four dakinis, namely Vajradakini, Ratnadakini, Padmadakini, and Vishvadakini.

Mahanaga (Sanskrit, Mahānāga). “Great Naga”; A member of the entourage of a Nagaraja.

mahasiddha (Sanskrit, Mahāsiddha). “Great Adept”; A Tantric master with strong enough powers and abilities to become a teacher.

Manidhari (Sanskrit, Māṇidhāri). “Gem Bearer”; The son of Avalokiteshvara in a special Kadam teaching where Avalokiteshvara, Shadakshari, and Manidhari represent a father, mother, and son.

Manjushri (Sanskrit, Mañjuśrī). “Gentle Glory”; The bodhisattva of wisdom. Many different forms with peaceful and wrathful appearances are known. In his most common iconographic form, he brandishes the sword of wisdom with his right hand and grasps the stem of a lotus, on which a book (the Prajnaparamita Sutra) rests, with his left.

Manjushri Vadisimha (Sanskrit, Mañjuśrī Vādisiṃha). “Gentle Glory, Lion of Speech”; A specific form of Manjushri. Usually he sits on a lion, expounding the dharma and holding two utpala-lotus flowers blossoming on his shoulders that support a sword on his right side and a book on his left.

Nagaraja (Sanskrit, nāgarāja). “King of Nagas”; According to traditional lists, there are eight great naga kings. In Tibetan art, they can appear supporting the throne of an enlightened being, but also being crushed under the feet of certain wrathful deities, or being worn as their adornments. A serpent king guards treasures and offers them to the Buddha and other deities or enlightened beings. He is traditionally a guardian of the Buddhist relics in stupas.

Padmadakini (Sanskrit, Padmaḍākinī). “Lotus Sky-goer”; A four-faced and four-armed dakini of the Mahamaya mandala.

Padmasambhava (Sanskrit, Padmasambhava). A teacher who is said to have propagated Tantric teachings in Tibet in the second half of the eighth century. Over time he and his role were magnified by faithful believers and he was portrayed as a uniquely important figure, resulting in a Padmasambhava cult. According to Buddhist sources, the indigenous deities of Tibet were tamed and bound to him by oath to protect the Buddhist teachings.

Parnashavari (Sanskrit, Parṇaśavarī). “Dressed in Leaves”; A Tantric goddess thought to cure diseases and heal injuries. In Tibetan art, she wears a lower garment and sometimes also an upper garment made of leaves. Various iconographic forms exist.

Pranasadhana Shri Devi (Sanskrit, Prāṇasādhanā Śrīdevī). “Life-Mastering Glorious Goddess”; A form of this rare deity was depicted at the tashi gomang stupa, but is not described in extant iconographic sources. Sherab Jungne gives a brief description of this deity in his inventory charts.

Pushpa (Sanskrit, Puṣpā). “Flower Girl”; A two-armed goddess symbolizing the offering of flowers.

Rahu (Sanskrit, Rahu). The leader of the Nine Planets. He symbolizes the north or ascending lunar node.

Rasavajra (Sanskrit, Rasāvajrā). “Indestructible Taste Girl”; A four-armed Tantric goddess symbolizing the offering of taste.

Ratnasambhava (Sanskrit, Ratnasambhava). “The Jewel Born”; One of the Five Buddhas. He is lord of the jewel family and occupies the south. His emblem is a jewel and his vehicle is a horse.

Rupavajra (Sanskrit, Rūpavajrā). “Indestructible Form Girl”; A four-armed Tantric goddess symbolizing the offering of form.

Saptadashashirshi Shri Devi (Sanskrit, Saptadaśaśīrṣī Śrīdevī). “Glorious Goddess with Seventeen Heads”; A specific form of Shri Devi possessing seventeen heads. She is briefly described by Sherab Jungne, but is completely unknown in iconographic sources.

Sarvavid Vairochana (Sanskrit, Sarvavid Vairocana). “Omniscient Brilliant One”; The principal deity of some mandalas, such as the Vajradhatu mandala.

Shadakshari (Sanskrit, Ṣaḍakṣarī). “Lady of Six Syllables”; The wife of Avalokiteshvara in a special Kadam teaching where Avalokiteshvara, Shadakshari, and Manidhari represent a father, mother, and son.

Shakyamuni (Sanskrit, Śākyamuni). “Sage of the Shakyas”; An epithet applied to Buddha.

Shri Devi Remati (Sanskrit, Śrīdevī Rematī). “Glorious Goddess Prosperous Goddess”; A special form of Shri Devi, who can be depicted riding on a mule with a sword in her right hand and a jewel-spitting mongoose in her left.

Sparshavajra (Sanskrit, Sparśavajrā). “Indestructible Touch Girl”; Name of two separate deities, a four-armed Tantric goddess symbolizing the offering of touch, and the consort of the meditational deity Akshobhyavajra.

Sparshavajra (Sanskrit, Sparśavajrā). “Indestructible Touch Girl”; Name of two separate deities, a four-armed Tantric goddess symbolizing the offering of touch, and the consort of the meditational deity Akshobhyavajra.

Tara (Sanskrit, Tārā). “Savioress”; She is considered both a bodhisattva and a buddha, a fully enlightened being. Numerous forms exist. Often a peaceful deity, she is called on for assistance in removing obstacles or providing protection from perils.

Vajradakini (Sanskrit, Vajraḍākinī). “Vajra Sky-goer”; A four-faced and four-armed dakini of the Mahamaya mandala.

Vajradhatu Mandala (Sanskrit, Vajradhātu maṇḍala) “vajra sphere”; A mandala based on a certain Tantra of the Yoga Tantra category. A common form of this mandala consists of thirty-seven deities headed by Sarvavid Vairochana.

Vajrapani (Sanskrit, Vajrapāṇi). “Vajra Holder”; A powerful bodhisattva.

Vajravarahi (Sanskrit, Vajravārāhī). “Vajra Hog”; A female meditational deity regarded as essentially the same deity as Vajrayogini. A snarling hog’s head is usually attached to the right side of her head. She can appear as the consort of Chakrasamvara but can also lead the deities of a mandala in her own right. She can take several known forms.

Vajravina (Sanskrit, Vajravīṇā). “Indestructible Lute Girl”; A four-armed Tantric goddess symbolizing the offering of music.

Vajrayogini (Sanskrit, Vajrayoginī). “Vajra Female Yogi”; A generic meditational deity that appears in various forms. She is Chakrasamvara’s consort, but can also appear alone. Her most common iconographic features include a curved knife, a skull-cup filled with blood, and a Tantric staff known as a khatvanga.

Vamsha (Sanskrit, Vaṃśā). “Flute Girl”; A two-armed goddess symbolizing the offering of music.

Virupaksha (Sanskrit, Virūpākṣa). “Having Deformed Eyes”; Guardian of the west. He holds a serpent noose and a precious stupa.

Vishvadakini (Sanskrit, Viśvaḍākinī). “Crossed (Vajra) Sky-goer”; A four-faced and four-armed dakini of the Mahamaya mandala.

Inside Asia Society's Golden Visions of Densatil Exhibition

Golden Visions of Densatil Opening Lecture

Parnashavari: A Healer Dressed in Leaves

Setting Densatil in the Treasury of Tibetan Art

Five Monks, Five Days, One Sand Mandala

Mandala: '100 Peaceful and Wrathful Deities' Come Into Being

Blog Posts

Video: Introducing Parnashavari, A Fierce-Looking Healer Dressed in Leaves

Interview: 'Densatil' Exhibition Recreates a Tibetan Buddhist's Path to Enlightenment

Video: Asia Society Museum Showcases Long-Lost 'Golden Visions' from Tibet

This is a preview of the official hardbound catalogue for Golden Visions of Densatil: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery, edited by Olaf Czaja and Adriana Proser.

ART TALK

Members-Only Lecture

Tuesday, February 18, 6:30 pm

Join Golden Visions: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery guest curator Olaf Czaja for an in depth perspective on this landmark exhibition.

SPECIAL EVENT

Creation of a Sand Mandala

Wednesday, February 19-Sunday, February, 23, 11:00 am-6:00 pm

Monks from the Drigung (Drikung) Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism construct a sand mandala over the course of five days, in conjunction with the opening of the Golden Visions of Densatil: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery exhibition.

ART TALK

Setting Densatil in the Treasury of Tibetan Art

Tuesday, February 25, 6:30 pm

Art talk with Tibetan art expert Katherine Anne Paul, Curator of Arts of Asia at the Newark Museum.

Major support for Golden Visions of Densatil: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery has been provided by The Partridge Foundation, A John and Polly Guth Charitable Fund.

Additional support has been provided by Lisina M. Hoch, Ann and Gilbert H. Kinney, Matthew and Ann Nimetz, Margot and Tom Pritzker Family Foundation, and Nancy Wiener.

We appreciate the support of Blakemore Foundation and the Ellen Bayard Weedon Foundation.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by The Julis Family, Asia Society Contemporary Art Council, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, New York State Council on the Arts, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

"An enthralling show ...

The atmosphere is so charmed

that you may be tempted to linger ...

Tibetan Buddhist art is irrepressibly alive."

Contact: Elaine Merguerian 212-327-9271, [email protected]

ASIA SOCIETY MUSEUM PRESENTS FIRST EXHIBITION TO BRING TOGETHER MATERIAL FROM FAMED TIBETAN BUDDHIST MONASTERY

GOLDEN VISIONS OF DENSATIL: A TIBETAN BUDDHIST MONASTERY

On view in New York from February 19 through May 18, 2014

Asia Society presents the first exhibition to explore the history, iconography, and extraordinary artistic production associated with the central Tibetan Buddhist monastery called Densatil that was destroyed during China’s Cultural Revolution.

The exhibition reunites a selection of reliefs and sculptures salvaged from the Monastery’s towering thirteenth- to fifteenth-century inlaid gilt copper memorial stupas (tashi gomang). Works on view are from public and private collections in the United States and Europe.

Golden Visions of Densatil: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery illuminates the artistry of the tashi gomang stupas—special memorial stupas masterfully designed and cast in relief by artists, including craftsmen from Nepal—and the spiritual journey toward enlightenment laid out in their imagery.

“Asia Society is pleased to present this exhibition, a first attempt to recapture the magnificent splendor of the Densatil Monastery and to create appreciation for its artistic, religious, and political aspects through new scholarship,” says Asia Society Museum Director Melissa Chiu.

The exhibition examines the unique design of tashi gomang stupas as huge, three-dimensional mandalas, each comprising a square base supporting six tiers with a stupa at the top. Historical sources indicate that there were eight tashi gomang stupas in the main hall of the Densatil Monastery; they housed the mortal remains of Buddhist adherents.

To help viewers visualize the stupas, a selection of photographs taken by Pietro Francesco Mele during Italian scholar Giuseppe Tucci’s 1948 expedition to Tibet are included. From February 19–23, monks from the Drigung (Drikung) school of Buddhism will create a colored sand mandala onsite in a small gallery. The completed sand mandala will be on display for the duration of the exhibition, and then ritually destroyed at its close.

Exhibition organization

Golden Visions of Densatil: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery is organized to give a sense of the six tiers that made up each tashi gomang stupa. Viewers move through the exhibition as one would have moved around the stupa, with the iconography of each tier detailing the path of the spiritual journey towards enlightenment taken by a Buddhist adherent. Viewers encounter protectors of the Buddhist teachings, female deities, offering goddesses, and deities representing higher esoteric teachings. The last section of the exhibition focuses on the final stage of the spiritual journey, represented on the tashi gomang stupa by a reliquary that would have formed the structure’s pinnacle and held the mortal remains of an enlightened adherent.

The exhibition is organized by guest curator Dr. Olaf Czaja with Dr. Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art at Asia Society. A fully-illustrated catalogue accompanies the exhibition with an essay by Dr. Czaja, a professor at the Institute for Indian and Central Asian Studies, University of Leipzig, excerpts from the journals of explorers Sarat Chandra Das and Giuseppe Tucci, and catalogue entries by Dr. Czaja and Dr. Proser.

About the Densatil Monastery

Built in 1198, the Densatil Monastery was founded at the site inhabited by the monk Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo (1110–1170). Evolving from a hermitage, the Monastery was situated in a remote area of central Tibet close to the northern banks of the Tsangpo River. At the height of its power, the Densatil Monastery was one of the wealthiest Tibetan monasteries in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The iconographic program created by the monk Jigten Gonpo (1153–1217), a disciple of Phagmo Drupa, laid the foundation for the tradition of erecting tashi gomang stupas to commemorate deceased abbots.

Throughout its history, the site figured in conflicts amongst monastic schools and factions, but it remained intact for centuries until its destruction during China’s Cultural Revolution. Fragments and pieces of the site were salvaged and later dispersed around the world. In 1997, a new assembly hall and small temples were built on the site of the destroyed monastery and in 2010, a new main hall was constructed. Under the auspices of the Tibet Autonomous Region Ministry of Culture and the Drigung (Drikung) Kagyu school, reconstruction of the Densatil Monastery continues today.

Exhibition support

Major support for Golden Visions of Densatil: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery comes from The Partridge Foundation, A John and Polly Guth Charitable Fund.

Support has been provided by Lisina M. Hoch, Ann and Gilbert H. Kinney, and Matthew and Ann Nimetz.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Contemporary Art Council, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, New York State Council on the Arts, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

Related programming

In order to provide additional context for the exhibition, Asia Society has organized the following:

• February 4–May 4: Lobby installation Himalayan Sculpture from the Asia Society Museum Collection, featuring four sculptures from the Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection which is a major part of the Asia Society Museum Collection.

• February 18: Members-only exhibition lecture with guest curator Olaf Czaja.

• February 19–23: “Creation of a Sand Mandala,” live with monks from the Drigung (Drikung) Kagyu school of Buddhism.

• February 25: Art talk on “Setting Densatil in the Treasury of Tibetan Art” with Katherine Anne Paul, Curator of Arts of Asia at the Newark Museum.

For more information on the exhibition and related programming, including public viewing hours for the creation of the sand mandala, visit AsiaSociety.org/NYC.

Plan Your Visit

725 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10021

212-288-6400