Observing Chinese Language Classrooms

Once your school has implemented a Chinese language program, it’s time to assess the quality of instruction. By keeping in mind some telltale signs, even non-Chinese speaking observers can suggest improvements.

Classrooms should be lively, both visually and in sound, said Betsy Lueth, director of the Yinghua Academy, a Chinese immersion school in St. Paul, Minnesota. Lueth spends a lot of time coaching the school’s teachers.

“Look for noise and chaos, quite frankly, Lueth said. “For many of our teachers that was a difficult thing for them to grasp: that noise and chaos were an okay thing.”

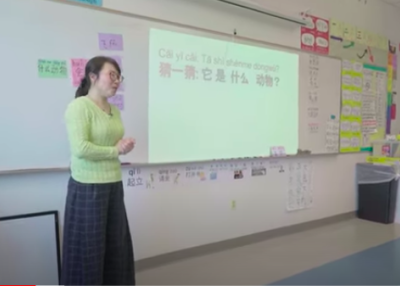

Classroom design

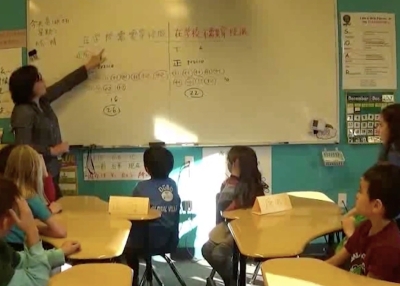

At the Yinghua Academy, everything from tables and doors to toy bins and schedules is labeled in Chinese characters. Hard-to-understand words are accompanied with pictures to aid in learning.

“We want to surround the kids with a print-rich environment, and we want to surround them with language,” Lueth said. “It’s a very important part of the acquisition process.”

Myriam Met, a former supervisor of foreign language instruction for more than 25 years, said the physical classroom space should support learners who are struggling.

“It’s nice to have an attractive room,” Met said. But “I need to be able to look on the board, look around the room and find what I need to do my work.”

However, not all foreign language teachers have their own rooms; in those cases, Met suggests asking the room’s teacher for a bulleting board or volunteering to decorate and post student work in the hallway. Another option: use traveling carts that hold large posters.

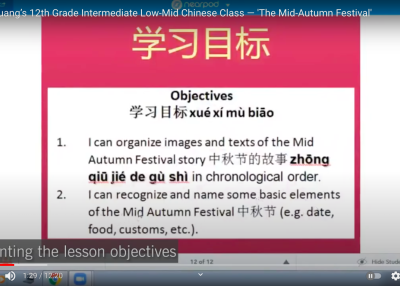

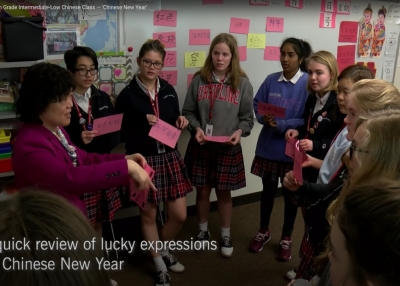

The physical space in the classroom is also a good place to set learning expectations, said Jacque Bott Van Houten, world language and international education consultant for the Kentucky Department of Education. Daily goals should be posted and stress function — like ordering from a menu or introducing family members — over grammar.

Students hear the target language

Lueth said the Yinghua Academy has a strict rule about not allowing teachers to use any English in the presence of children.

Children will not understand every word being said, she said. But demonstrative tones and body language can help kids understand words they have not yet learned.

Met said teachers should speak the target language; translating gives students the opportunity to tune out when the foreign language is spoken. An exception: when providing brief instructions in English will free up more time for using target language.

“I’m ok with 30 seconds of English to explain a complicated activity,” Met said. But “if you are hearing English, you are not getting enough opportunity to internalize the language.”

Students speaking the target language

“The only way you become a proficient language speaker is to speak,” Met said. “If you don’t do it, it stays hard.”

And students will be more engaged if communication has meaning and purpose.

“In real life, no one will come up to you and say, ‘Are you a boy or a girl? Or, Betsy, what is your name? Or, you are wearing a brown jacket,’” Met said. “And if they do, you should quickly walk away from them.”

Teachers can coax students into offering longer verbal responses by pausing between asking a question and calling on a student for a response; this gives students time to collect their thoughts.

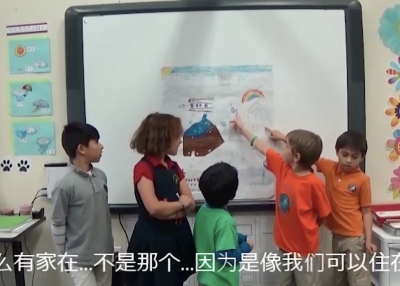

First graders at the Yinghua Academy, for example, practice speaking by breaking into pairs and telling each other jokes. Children also break into groups to read a story and then re-tell it.

Met said administrators and teachers observing Chinese classrooms should also look for how teachers set up pairing and group work. It should be structured in such a way that every student has to have a turn.

Of course, teachers need to keep an eye to ensure kids are engaged.

“Too often teachers teach as if the room were empty. They go right on teaching as if the kids weren’t there at all,” Met said. “That is not learning. It happens to be teaching, but it’s not resulting in student learning.”