Emakimono

Japanese Picture Scrolls

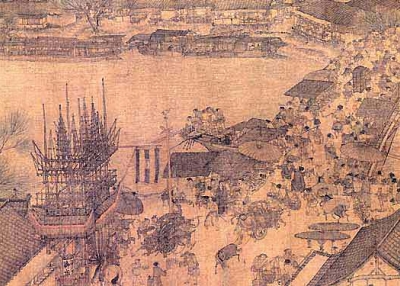

During the 11th to 16th centuries, painted handscrolls, called emakimono, flourished as an art form in Japan, depicting battles, romance, religion, folktales, and even stories of the supernatural world. The handscroll may have originated in India, but it was transmitted from China to Japan in the 6th or 7th century along with Buddhism. In addition to providing entertainment, these scrolls played an important part in the spread of Buddhism.

Unlike the vertical hanging scrolls with which we are familiar, emakimono are horizontal. Composed of a series of scenes rather than one entire scene, these handscrolls may be painted in many colors or only black ink. They are usually created by joining together several dozen sheets of paper or, occasionally, silk. A cover is attached to one end and a roller to the other. Emakimono vary in size, measuring an average of 30 centimeters (1 ft.) in width and 9 to 12 meters (30 to 40 ft.) in length. In most cases a single story is portrayed in one to three scrolls.

A handscroll is read by opening it to arm's length and viewing one portion at a time from right to left. Most contain a calligraphic explanation of the story, either at the beginning of the scroll or directly preceding each scene.

Technically, repetition is common in emakimono; a character may be shown over and over again with only the background changing. Frequently the portraits of a scroll's heroes are painted larger than those of other characters in the story.

Activity

There are several ways to make emakimono. One way is to divide the story into sections and have several people make a scroll together, as was common in medieval Japan. The drawings or paintings can be done on separate sheets and glued together afterward, with about one-half inch of overlap. A scroll can also be made on a single roll of paper, such as white shelf paper. Any type of print art medium—paint, crayons, felt-tip pens, colored pencils, or black ink—can be used.