China Night: An Annual Performance That Enhances Learning. PART I

What Does China Night Look Like?

China Night is an important event for students to integrate what they have learned in their Chinese classrooms and share their knowledge with the school communities. However, organizing an exciting China Night event is not easy work and can be challenging. In the following two-part article, Heidi Steele shares her experience planning China Night at Gig Harbor and Peninsula High Schools in the Peninsula School District of Washington state, with the hope of offering advice and strategies on how to make this a rewarding experience for students, teachers, and the community.

In Part I of her article, below, Heidi describes China Night and reflects on its purpose for her students and her community.

Six years ago, we began holding an annual China Night (中国之夜, Zhōngguó zhī yè) performance in February for friends and family of the students in our Chinese language program and the wider school community. China Night is a great opportunity for students to showcase their knowledge of Chinese language and culture through performances and artwork.

This event serves the following purposes:

- Gives students an opportunity to share what they are learning in class.

- Gives administrators, parents, and community members a window into our program and a chance to experience Chinese culture.

- Provides a venue for students to integrate their other passions into Chinese class.

- Gives students a welcome break from the usual routine in the middle of the school year.

- Inspires and motivates beginning students as they work alongside more advanced students.

- Strengthens students’ sense of community as they work together to produce a show.

As we are beginning to develop ideas for China Night 2016, I thought teachers might enjoy learning about the model my students and I have developed. Please use these ideas as a jumping-off point to create, modify, or extend performances that you are planning in your own programs.

A note about cost before we get into the details: As an Asia Society Confucius Classroom, we have the good fortune of having funding that we can use for China Night. However, with strong support from parents and from your school administration and a good amount of creativity, putting on an annual performance should not be cost prohibitive.

What Our Performance Looks Like

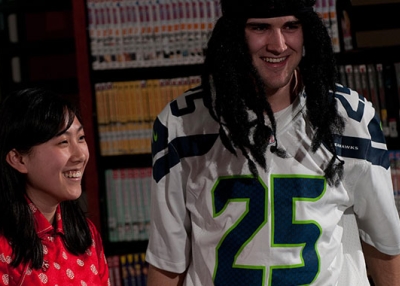

China Night varies greatly from year to year, but has generally included both popular and folk songs, modern and classical poetry, rehearsed and improvised skits, tongue twisters, nursery rhymes, instrumental pieces, story telling, speeches, videos, flash mobs, martial arts, and dance routines, among others. Many pieces are also accompanied by original artwork created by the students. At intermission, the students serve tea and Chinese snacks that they have prepared themselves. And some years, students choose an overarching theme for the performance. The entire performance runs for approximately an hour and a half.

The acts may be performed by one or two students, a small group, an entire class, or all of the students in the program. Each year, two advanced students volunteer to be the MCs for the evening, giving opening and closing speeches and introducing each act.

Students speak in Chinese for the entire performance. This gives the audience a chance to experience “surround sound” Chinese and to see that their students can function in a Chinese-only environment. During the performance, I stand on one side of the stage and interpret what the students are saying in English. For short poems, we write the English translations on big posters that are displayed on stage as the students are reciting the poetry. For songs, we project rolling lyrics in English for the audience to read as they are listening to the music. The printed program is also bilingual, listing the names of each act in both Chinese and English.

Developing Content

First, let me describe some potential pitfalls. I have identified four shortcomings in performances over the years:

- The teacher literally runs the show, deciding what acts the students will perform and in what order. The teacher also teaches all of the material, provides the props and costumes, handles most of the publicity and logistical arrangements, and so on. In many performances, the acts tend to focus on predictable themes and reflect little of the students’ own creativity.

- The individual acts are “pre-fab.” If the students sing a song, they are often accompanied by the original soundtrack or YouTube video. If they perform a skit, they are handed the lines by the teacher to memorize. If an image accompanies a poem that the students recite, it has been downloaded from the Internet.

- During the entire process of preparing for the performance, students speak in English. In effect, language learning is put on hold as students rehearse their acts. Students’ language proficiency actually slips during the time they are preparing for the performance, and they have to make up what they’ve lost afterward.

- Students are graded on their participation and/or performance. As a result, they see the performance as a class assignment rather than as an expression of creativity and teamwork.

As our China Night performances have evolved, I have worked to address these issues, and the process described in this two-part series includes advice on how to do so.

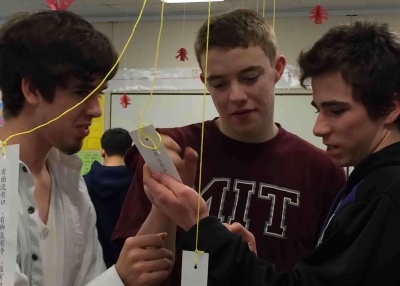

After the first couple of years, I realized that it was too difficult to prepare for China Night while teaching the regular curriculum, so I began running a China Night “mini-term” that runs for three to four weeks leading up to the show.

At the beginning of the mini-term, we brainstorm ideas for what to include in the performance. Any poem, song, or craft project that we have already learned in class can be incorporated into China Night, and we also create new material as we go. For my Chinese 1 classes, I ask them to describe the kinds of things we have performed in the past to help them get ideas rolling. For my Chinese 2/3 classes, we hold an informal meeting in which the students make suggestions and tell me what they’d like to perform. I facilitate the meeting and jot down their ideas, giving my own two cents here and there.

Every year, students come up with new ideas. For example, one year we sang the school fight song in Chinese. Another year, a student demonstrated his ability to solve math problems on the abacus. This past year, students played an instrumental piece by the band Shanghai Restoration Project while the audience viewed a photo montage of candid photos of students in class.

Throughout the mini-term, the content emerges organically as a collaborative effort between my students and me. Sometimes I invite particular students to share talents I know they have, but more often students come to me with their own ideas for pieces to perform. By the second week of the mini-term, we have a pretty firm list of the pieces we will include.

Suggestions for particular types of performances

Stories

If a small group wants to perform a traditional Chinese tale, I bring in children’s books and give them some options of stories that I think they can perform at their proficiency level. Once they select the story they want, I write a simplified version that includes both narration and acted parts. Last year, a group of Chinese 1 students performed “Three Monks” (三个和尚, Sān gè héshàng), and the year before students performed “Polliwogs Looking for Mama” (小蝌蚪找妈妈, Xiǎo kēdǒu zhǎo māmā). Typically, two to four students take turns narrating the story, while others play the different roles. You can vary the difficulty of the speaking parts to accommodate the proficiency levels of the students in the group. To ensure that stories actually increase students’ language proficiency, I require that the students learn all of the new vocabulary and syntax in their lines rather than simply learning the general meaning of each sentence.

Songs

I avoid well-known favorites such as “Jasmine Flower” (茉莉花, Mòlìhuā) unless a student brings one of these songs to the group, and instead suggest less commonly known songs that somehow capture sentiments that resonate with young people. We sing everything from songs popular in China right now to older folk or traditional melodies. In recent years, my students have accompanied all of the songs with live instruments rather than playing a soundtrack. Sometimes I am able to find the guitar chords or piano sheet music online, or sometimes a talented student transcribes the parts for various instruments by ear. Either way, the live accompaniment adds to the richness of the performance, and students find it extremely gratifying to bring their love of music into the show.

Artwork

For each of the songs and poems in the performance, students volunteer to create artwork that depicts the image each piece elicits in their mind. Just as with musical students, artistic students love being able to integrate their passion for drawing and painting into the performance. I create a slide show that contains scans or photographs of all of the artwork, as well as videos, recordings, and so on, and a student advances the slides as the performance runs.

Poetry

We typically include both classical and modern poems in our performances. For classical poems, I bring in an illustrated book of poetry and let students choose the poems with imagery they like. We use classical poems as an opportunity for students to work in a concerted way on their tones. For modern poems, I often have students page through a wonderful collection of modern Chinese poetry with English translations, Push Open The Window, Contemporary Poetry from China, edited by Qingping Wang, and let them select a poem that moves or intrigues them in some way. As part of their preparation, we discuss what the poem is about and do our best to interpret the meaning ourselves. I also research the poet’s life and read literary analysis of the poem on Chinese websites and then share the highlights with my students.

Skits

The beginning students usually write their skits ahead of time. The more advanced students usually do an “unscripted” skit. For the latter type, they work out a general storyline, but stop the performance at key junctures and ask the audience to tell them how the skit should continue. Based on the audience response, they continue the skit with one storyline as opposed to another. For example, if the scene is a coffee shop in which a girl and her boyfriend are meeting for a date, the students may stop the skit just as the two teenagers are sitting down and ask the audience whether the girl is going to a) break up with the boyfriend, b) ask the boyfriend to the dance, or c) tell the boyfriend she has a terminal disease. Depending on the audience’s choice, they will continue acting in one direction or another. These are my favorite to interpret into English, because I have no idea what will come out of the students’ mouths and have to simply go along for the ride.

Speeches

In every show, one or two advanced students prepare a speech about a topic of their choice. I work with them individually, revising their drafts and helping them with memorization. These speeches represent the highest levels of proficiency that students reach in my classes, and they give parents a chance to see what their students will be able to achieve if they continue with their studies.

∨ Show suggestions for particular types of performances

Next month, Heidi will continue her story and discuss how she successfully engages students and prepares for China Night.